Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2024-08-15 - An Abolitionist, A Southern Secessionist & Frontier Vengeance Along the Oregon Trail with Josie Smith (54 minutes)

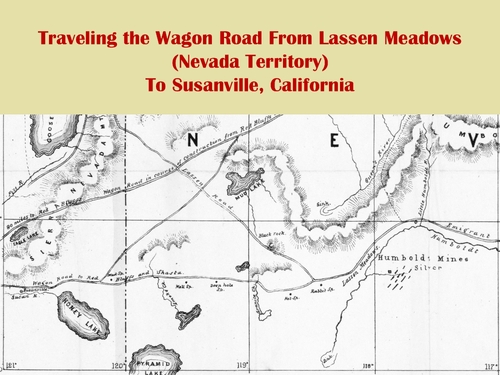

Five years after fiery abolitionist John Brown was hanged in 1859 for his failed raid on Harper's Ferry Arsenal, his wife Mary, three daughters, and son Salmon traveled overland by wagon to start a new life in Red Bluff, California. Author Josie Smith will be sharing about their journey that nearly ended in disaster on the Oregon Trail when a wagon train of "Tennessee rebels of the worst kind" discovered who they were and chased them along the trail.

The Brown family and subsequent historical journal and newspaper articles never identified these "Tennessee rebels" or why they doggedly pursued the Browns until now. This presentation by Josie Smith will present her research that finally reveals their surprising identity and the real reason behind the tension between the two wagon trains, which had nothing to do with the abolitionist movement.

This story spans pivotal moments in United States history and reaches back to the crown of England. It's also a story about links. Several years after their near fatal encounter along the trail, both families were destined to meet again as they set roots in Northern California.

The Brown family and subsequent historical journal and newspaper articles never identified these "Tennessee rebels" or why they doggedly pursued the Browns until now. This presentation by Josie Smith will present her research that finally reveals their surprising identity and the real reason behind the tension between the two wagon trains, which had nothing to do with the abolitionist movement.

This story spans pivotal moments in United States history and reaches back to the crown of England. It's also a story about links. Several years after their near fatal encounter along the trail, both families were destined to meet again as they set roots in Northern California.

Author: Josie Smith

Published: 2024-08-15

Original Held At:

Published: 2024-08-15

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

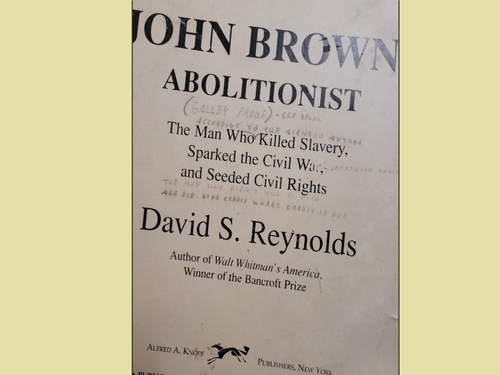

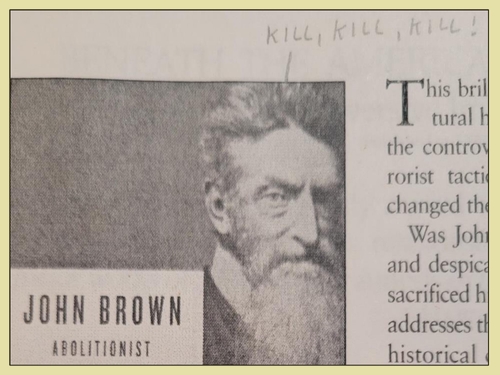

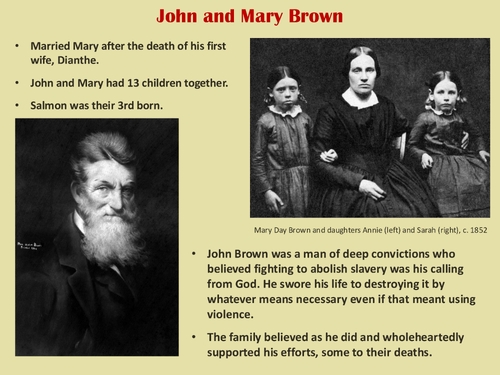

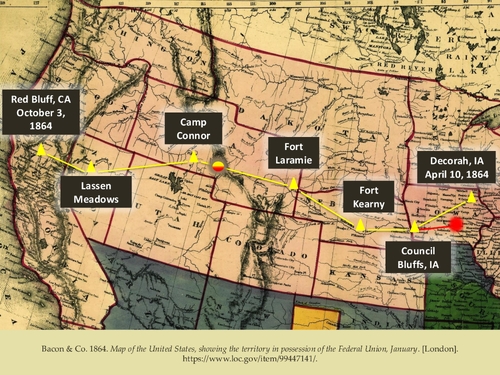

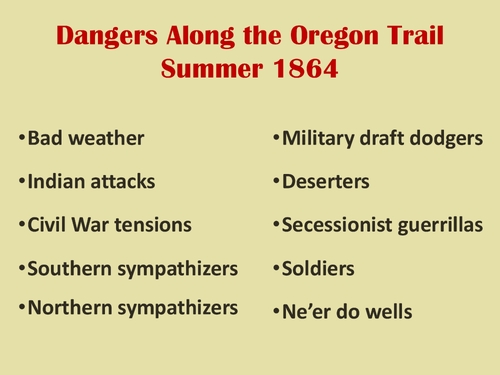

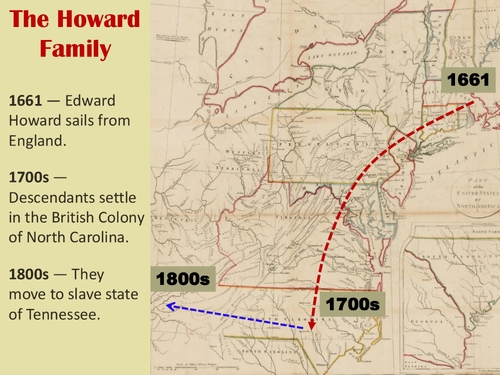

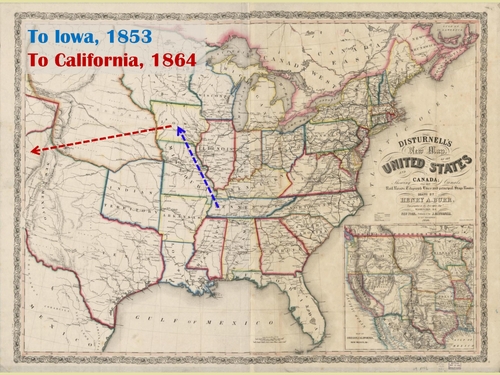

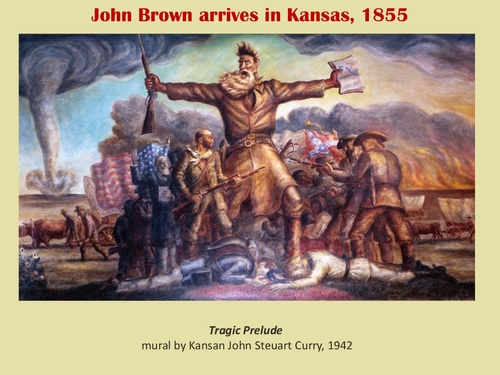

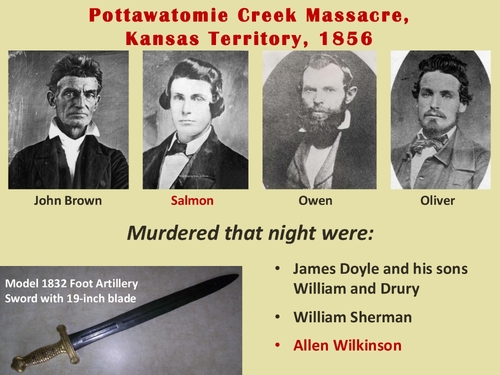

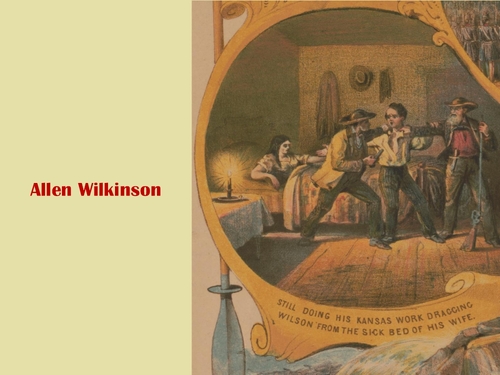

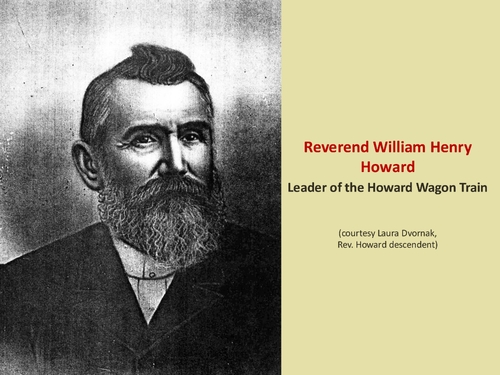

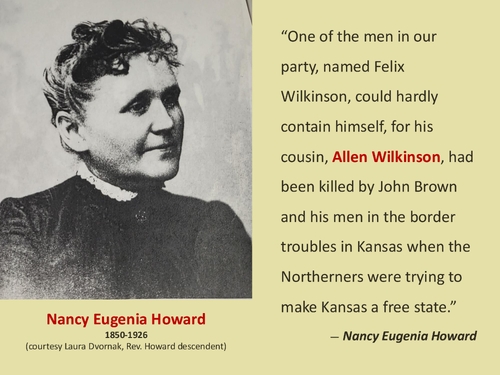

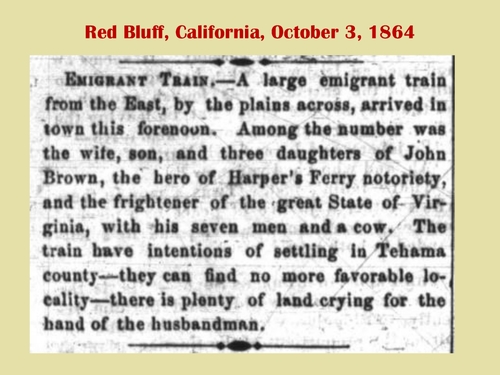

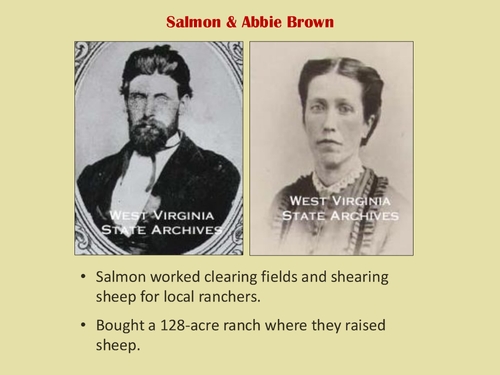

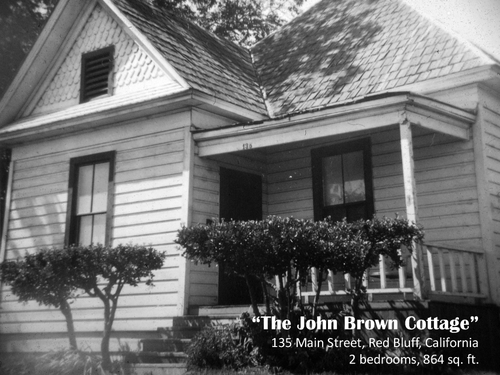

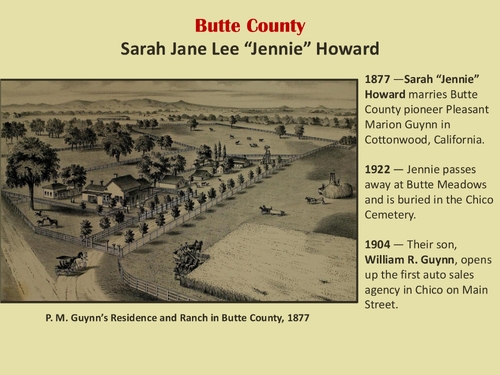

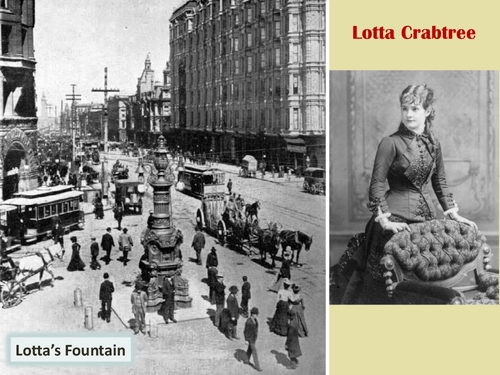

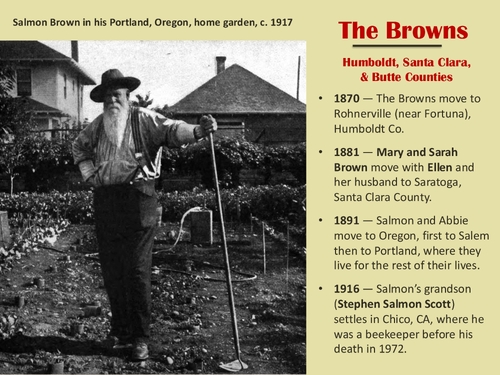

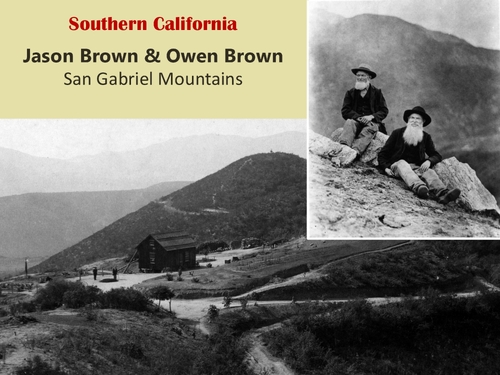

Thank you for coming to my presentation to learn about the Brown family coming to California on the Oregon Trail in 1864, and why they almost didn't make it. My presentation is based on accounts that were written by a son of John Brown, John Brown, the abolitionist who was well known for Harper's Ferry being executed for his failed grave at Harper's Ferry. When the family came across on the Oregon Trail, later in life Salmon and his wife Abby wrote their accounts about it. In all these accounts they talked about a confrontation that almost ended in bloodshed, but they never identified who that white portraying was or really why there was this tense moment on the trails. Their version was published over the decades by newspapers all across the United States, and there's one version from the late class of news that was published in 1939 that is like the story that historians to the state cite and refer to when they write the story about their overland journey by wagon. During my research with newspapers, newspapers will edit for space constraints, so it's an edited version. I found through Google a archive in West Virginia that contained their unedited accounts, and from these accounts and from a letter I discovered not only who this wagon train was, but the actual reason why they chased the Brown family over the Oregon Trail for a week trying to get to them. And this is a story about the who and the why, but it's also a story about connections, because as I was putting this together, there are connections that be made between these two families and the locations and we'll get into that. I found an indirect connection between one of those family members and Nevada County, which I will get into later. But we have a lot of ground to cover, so we'll get to it. I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for Wilmer Fay. This book, John Brown's family comes to Red Blood, was his master's thesis at Chico State. He taught history and geography for 30 years at Red Blood High School, and Anger published this book in 1986, the Association for Oregon, California Historical Research. In 2019, we didn't have copies of this book, so we thought it might be a good idea to reprint it again. We found Mr. Fay, he was still alive, he was in his 80s in frail, and when he found out that we wanted to republish his book, he was thrilled. To quote him, he was tickle-pink. As we do with Anger, if there is history, we can add to a book that we know of that the author didn't know of. We talked to them and asked, hey, can we add this either as an appendix or separate chapters or whatever. Mr. Fay, bless his heart, he said, do whatever you want to do. He gave us his notes from back in the 1960s when he was doing research for this, and he was thrilled. Unfortunately, he never saw this book, he passed away four months after we met him. I think we did his memory proud with this book, and he would be proud to see it. This presentation won't focus on John Brown, but I need to give you a little context about the man. When I start researching, I really immerse myself in this subject. To do that, I buy books. It's a great reason to buy books. One of the books I bought, to understand The Man in the Tines, was by David Reynolds, John Brown Abolitionist. We came out in 2006. It's a great overview of John Brown's life, who he was, why he was, and the politics of slavery in the 1850s, which paints today's politics look like nursery school. It was so intense. There was no, it was one side of the outside. There was no coming together. I jump around in his time. People either loved him, or they hated him. And of course, depending on if you were a northerner, an abolitionist, you loved him. If you were a southerner, you hated him. He was a terrorist in their minds. He scared them because he was just one man, but he was able to stir up a lot of trouble. I didn't realize that the animosity carries to this day. A lot of things that he did back in the day is still debated, the pros and cons of it, and some people still can't stand them. I had the luck of finding a galley proof of this book on eBay for a few dollars. It was proofed, it was a content editor who had gone through it. And this editor, I don't know who this person was, I could never find out, even from the seller, knew their history because this book is full of handwritten, penciled notes on certain facts in there. But they also penciled in how they felt about John Brown, and I'll give you some examples. The title page here says the man who killed slavery, sparked the Civil War, and ceded civil rights. Well, on the half-title page, I don't know if you can read it, but I'll read it to you. Where it says the man who killed slavery, the editor wrote, according to the airhead author, sparked the Civil War, Jefferson Davis, and ceded civil rights. The man who didn't kill slavery, aid did, give credit or credit is due. And then you didn't get that feeling that this person didn't like John Brown. There's this page, kill, kill, kill. And then this page, why isn't there a rope around his neck? Pretty intense, and this book came out in 2006, so this copy editor had to have it 2004-2005. So, pretty strong feelings, even to this day. But let me tell you a little bit about John and Mary Brown. He married Mary after the death of his first wife, Diane, who she died giving birth to their seventh child. When Mary, he went on to have 13 more children. Solomon, who plays an important role in this story, was their thirdborn. John Brown was a man of very deep convictions. He found slavery at heart, and he believed it was his calling from God to destroy it and get rid of it by any means possible. And if that meant violence, so be it. And his family wholeheartedly supported him and agreed to him, even where it led to some of their deaths. Which it did at Harper's Berry, October 16th, 1859. On that day, John Brown led a group of men, including two of his sons. Another son held back and ran off. He escaped. But he led 24 raiders, 24 men, hoping to start a slave rebellion. It failed. It failed because of John Brown's poor plan and his indecisiveness. He and his men, the ones who survived, were captured by future Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Jeff Stewart. Of the casualties on that side, the U. S. Marines suffered one dead and one wounded. Virginia and Maryland militia had eight wounded. Civilians, they killed nine civilians, nine were wounded. Of the 24 raiders, 11, including his two sons, Watson, who was 24 years old and Oliver, who was 20, were either dead or dying. Brown was wounded. Seven were captured. One died in jail. Five others escaped, including his son Owen and John Brown. He was wounded, but captured. And two months later, he was hung on December 2nd, 1859. He was convicted for murder, fermenting, insurrection, and treason. He's the first man in the United States history who was executed for treason. After his death, Mary was allowed to bring his body back to the homestead in North Elda, New York, which is near Lake Placid in the Andorraque Mountains. And this is a picture of the family home, and that is the gravestone of John Brown. It was right there, and I believe the sons are buried there too, and several of the Harper Ferry raiders were buried there over the years. But life was hard in North Elda. It was never easy, but they started looking west. It's like, it's time to move. Because the cold climate, you couldn't grow much in the short season. They could grow potatoes, a few other vegetables. They harvested from their sugar trees, maple syrup, and they made sugar from that too. An uncle told them about California after he came back after a visit. He said, California's a great place. Mary thought it'd be a great start for her three daughters who were still living with her. And Solomon Brown wanted to move. He had been given a commission in the Union Army in 1862, and that he was very proud of it. Once the officers discovered that he was going to be in their unit, they wrote a letter formally protesting his presence. They felt that if they went down south and the Confederates knew that there was a son of John Brown in that unit, it'd be like a bullseye on their back. They didn't want that extra tension and pressure during a fight or encounter. Solomon, to prevent any trouble, resigned his commission, but he was very disappointed and bitter about it. He wrote later, he said, I had been told the best service I could render my country was not to serve it. I decided then and there to go west, the further the better, so I began making preparations to go by wagon to California. So he and his family and Mary, they sold their homesteads, took a train, and went as far west at that time as they could by rail, and that was basically the Midwest, and they made it to Decora, Iowa in the fall of 1863, and they wintered over there. And at first they thought that, hey, this is a nice place, maybe we'll settle here. But winter again, it was very cold and reminded of the mountains where they came from, and they said, no, let's go to California. So the following spring in April of 1864, they outfitted three wagons, and they joined an estimated 40,000 other people that year to travel the trails to the west in the Great Migration. They had three wagons, one wagon was for Mary, I'll point her out, she's here, her daughter Annie, Sarah, and young daughter Ellen. They rode one wagon, Solomon and his wife had the other wagon with their two young daughters. The third wagon was for Solomon's prize, Marino's sheep, he brought six sheep with him to California, only two made it. But he brought two, they would ride in the wagon during the day, and at night they'd be let out so they could graze, and then in the morning they'd be put back in the wagon and off they'd go. They also had milk cows with them, that they would milk at night, and then they would put the milk or the cream on the wagon somewhere, and during the day the rocky motion of the wagon would germ them butter, so they'd have butter to give them that night, fresh butter and butter, which was pretty clever. Their additional provisions, they made this themselves, hard tack, dry mashed potatoes, and beef sausages, which they supplemented with dried fruit, bacon, and fresh milk and butter. So off they went. They started to Cora, Iowa, April 10, 1864, came down to Council Bluffs, Iowa, crossed the Missouri, went along the Mormon Trail, and then joined the Oregon Trail by Fort Kearney, went up to Fort Laramie, and went to Camp Connors, so to Springs, and from there they took the, they're a subtlet cut off, I believe, to the California Trail, where at Lassen Vettos, which is near Bright Patch Reservoir now, they took the new Red Bluff-Susanville wagon road straight to Red Bluff, and they arrived there October 3. There's two things I want to point out with us now. This little circle right here, that's another family getting ready to leave and head west to California, just like the grounds. This family, they did the same thing, crossed, went along the trail, and joined the Oregon Trail at Fort Kearney, went up to Fort Laramie, and just before the, what is it, the, let's see, it is, South Pass in modern-day Wyoming, the true two wagon trains met and joined together. This wagon train that came from Marshalltown, Iowa, depending on the sources, was either, it was between 40 and 80 wagons in size, which is huge, and it was one extended family who were traveling west. Now the reason why they joined is together, especially smaller wagon trains, it was pretty common for wagon trains to join, is that there were a lot of dangers along the trail. You had that weather, you had the threat of Indian attacks or Indian attacks, you had the Civil War tensions, you had southern sympathizers, you had the secessionist guerrillas, you had the free-serve guerrillas, you had military draft dodgers, because in 1863, the Construction Act was the first national wartime draft, which required all men between the ages of 20 and 45, this included immigrants who were working towards their citizenship, they had to serve in the Army. And so there were a lot of draft dodgers and deserters from the Army on the trails that year, and you had to worry about soldiers too. The 1863 enrollment act gave any soldier, even a private, the right to stop and search your wagon. If you had any military item, gun, clothing, a horse that had a military brand on it or whatever, or a rifle that came from one of the arsenals like Harper Ferry, even if you could prove that you bought it or bought it legit, and you were not a military man, they could confiscate it, and that happened a lot along the trail. There's many accounts where rifles and such were taken from the settlers, and there's some accounts where the settlers said no, and they went after the soldiers and took it back, they said they needed it. And then you had your basic criminal who would prey on wagon trains, rob, kill, and make it look like the Indians did it, or they would damage, so there were a lot of dangers, so there were safety in numbers. And Abby Brown wrote that they were happy to join this larger wagon train because a few days or a week before, they had encountered 250 Sioux warriors, the encounter was okay, nothing happened, but it frightened them. So when they joined this, they thought that joined the bigger wagon, it's like they were safe. And she wrote, she said we thought it best to join some train, especially as we were hearing of murders being committed. But then she said it wasn't long after we joined that we know something wasn't quite right. And then a Solomon's sister, Annie, wrote, there was a train of Tennessee rebels of the worst kind who got us into their company and were going to kill Solomon and doubtless the rest of us. And then Solomon Brown wrote later, he said, we had escaped death from the Indians by joining the larger train, but it proved we had jumped out of the frying pan into the fire. Most of the train were southerners, made up of some of the roughest elements, who had not forgotten the part we took in the border warfare when Kansas and Missouri were in a state of perpetual conflict over the extension of slavery into Kansas. And for the part John Brown and his family had taken against the South at Harpers Ferry. And this is always intriguing, because I personally, if I had someone coming out for me and wanting to kill me, if I was writing my memoirs, I'd be naming names. I wouldn't let them going on this in history, I'd be naming names. And it was intriguing that it's like, who were these rebels of the worst kind, and why did they pursue the Browns so doggedly wanting to kill them? It was one of those questions that I thought, well, how would I find out who this wagon train was out of thousands of wagon trains that year? It would have to be dumb luck, but it wasn't the back of my mind that it would be really nice to find out who they were. Shelby Brown, civil war historian Shelby Brown once noted that. He said, I can't begin, I'm sorry, thank you, Shelby Foote. I can't begin to tell you the things I discovered while I was looking for something else. And that's true. Looking for something else is how I discovered the identity of this wagon train and the why. And unlike Mr. Foote here, I mean, Ty Desk, books all lined up nice and neat, he's sitting there relaxed and with the requisite historian cardigan, that's great. When I'm looking for something else, usually three o'clock in the morning, like this, I'm like this. But I found out who these people were, and it's an amazing story of two families, both who were abolitionists, but one was Union, one was Confederate, and they weren't linked because these Tennessee rebels of the worst kind resented the Browns and their attempts at devolution slavery. It was much worse than that. They were linked by a murder that happened years previous. So let's start with the who. Who were these people? Well, Abby Brown mentioned them in a letter, in a little post script, in a letter she wrote to her friend in 1914. And she said six years after our escape from the rebels, Mr. Brown saw one of them. Mr. Brown asked him if his name was Howard, and if he had belonged to the Howard train that crossed the plain six years before. He acknowledged it, and Mr. Brown told him who he was. Howard train, I finally had a name. So I started Googling it, and I hit pager on an online archive from a little historical site in Louisiana. They had printed an account about the Howard wagon train. From that account, I learned that this wagon train, and like I said, was one very large extended family of the 80 wagons in size. They were also known as the singing wagon train because these people were very musical. And if you can imagine, you've got all these wagons trumbling along the organ trail. You've got all the sounds, the wheels and the wagons creaking, men talking and the animals and stuff. Suddenly someone starts singing. Someone else starts singing with them. And suddenly, the entire wagon train is singing a song. I mean, it's just amazing. I mean, how would that have sounded, you know? So they were known as the singing wagon train. This wagon train was led by Reverend William Henry Howard, a Methodist Episcopal Church South Ex-Order, who's a lay speaker who could hold meetings and evangelize, lead prayer. But he was one step down from becoming like a lay creature. Now, let me introduce you to the Howard family. In 1661, Edward Howard was the seventh-born son of a very minor branch of a very noble, prestigious family in England. But as the seventh son, he had no chance of inheriting any wealth, titles or anything. That all went to the first born. All sons who were not the first born were given two choices. They could join the clergy or they could join the military. But by this time, there was a third option, and that was to create a new life in the new world, the colonies. And that's what he did. He set sail, and in 1661, he arrived in Boston, had a family, and by the 1700s, his descendants, some of his descendants heard of some great land in the colony of North Carolina, and went down there and settled in a town called Fayville. I grew up in Fayville. You know, it's like there's a connection. It's like that gave me goosebumps. It's like, whoa, there we go. Now, some of these down there in North Carolina, they did have slaves. But by the time the family of the both of them moved to Western Tennessee, they were staunch abolitionists in the early 1800s. Then, let's see, from Tennessee, they moved to Iowa, because as abolitionists in a slave state, that didn't sit well with their neighbors. So they decided, okay, we're going to go to the free state of Iowa where some other families moved to, and we're going to settle there. That was all well and good, but while being abolitionists, they were staunch southern sympathizers, which didn't sit well with their neighbors up there. So they decided, spring of 1864, we want to move as far away from this hassle as we can. That meant California. That's how these two wagon trains met. And before we go back to the Oregon Trail, let me introduce you to the noble family they're related to. This one, Henry VIII, and famous for his six wives. His second wife was Anne Boleyn. Her mother was a Howard. Anne was executed, beheaded, because she could not give Henry the male heir he desired. Only a worthless girl who later grew up became queen Elizabeth I. His fifth wife was Catherine, a cousin to Anne. Catherine Howard, she lost her head because of her infidelities. When she married Henry, she was like 19 years old. Henry was approaching 50 and not in the best shape. So she had her lovers, he found out he broke his heart, she lost her head. So now we, now you know the food, now we need to understand why that wagon train pursued the Browns. And for that, I need to give you a little context for the reason behind it. We have to go back to 1856 to bleeding Kansas and the night of cold blooded murder. Kansas became known as Bleeding Kansas after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Before that, when Emperor Territory entered the Union, Congress would decide if it entered as a slave state or as a free state. This kept a balance in both Senate and Congress as to the number of representatives. With this act, Kansas and Nebraska, the people who lived there were given popular sovereignty, meaning they would vote and decide on whether or not they entered as a slave or free state. Needless to say, people from the South and people from the North swarmed these territories. Northerners who wanted Kansas to become, you know, enter as free, they wanted to influence the vote. Same thing with Southerners, pro-slavery people. This resulted in years of incredible violence and political turmoil. Kansas was eventually admitted as a free state in 1861, but before they got to that stage of it, that's why it's called Bleeding Kansas because of the violence. And into all this, marches John Brown and several headless sons. They decided they were going to do whatever they needed to do to make sure that Kansas was admitted as a free state. And remember, it says, God given right to destroy slavery by whatever means possible, and if that even meant murder, so be it. And that's what exactly happened a year later. The Potawatomi Creek Massacre, which is still debated today, that happened on the night of May 24th, 1856. John Brown led four of his sons. Frederick is not, I don't have a picture of him, but Solomon, Olin, Oliver, Frederick, a son-in-law and two friends did a preemptive strike against five men in the Potawatomi Creek area. These men did nothing personally to Brown, to Brown, but their crime was they were pro-slavery people, pro-slavery sympathizers. That was their crime. John Brown and his men woke these people up. James Doyle and his three sons who were like 19, 20, 21, something like that. William Sherman and Alan Wilkinson. They got them out of their houses, dragged them out and slaughtered them with a 19-inch blade. The artillery sword was a 19-inch blade. They did that because one, it was quiet. They didn't want to use guns and blur surrounding neighbors. And it was to send a message to the Southern Democrats that there was someone out there who was not shy to bring Southern vengeance to their door. And that's why this is considered such a brutal massacre. People still debate, was John Brown right in doing this? Some people, even back then, said yes, he was. They were the target within his right to kill these men. They were bad men. Others saying it was murder. It was pure murder. Oliver, well, Oliver died at Harpers Ferry. But when he did, Salmon did say that Alan killed someone. And then Salmon made an interesting comment. He said, and then the other son killed the other one. Salmon names names except for this other son, which historians believe was him. He was involved in killing, I believe, one of Doyle's sons. But Alan Wilkinson, that's the name you need to remember in addition to Salmon. He is the connection to what happens in the Oregon Trail. After the massacre, there was a big investigation and witness statements were taken. And Alan's wife, Louisa, in her witness statement, said it was late at night, there was a knock on the door. And from outside, someone said, you are a prisoner. Do you surrender? And for whatever reason, Alan said yes. And he opened up the door and he let four men in. They dragged him out and his body was found the next morning, 150 yards from the house, hacked to death. This leads us to the reason, the reason for the conflict. Was it because, as the Browns asserted, and it's been carried throughout history in their accounts, in, you know, printed stories and newspapers and by historians, was it because of their fight to end slavery? Or was it for something else? It was for something definitely else. And this comes from a memory that was published in a newspaper that from Reverend Howard's young daughter, Nancy, who was 14 years old at the time of coming across on the Oregon Trail. And she was interviewed in her 70s and this is what she said. She said, while crossing the plains, we were overtaken by a small party with two or three wagons. The Indians were troublesome and one of the men in this party asked my father if they could join our wagon train. My father, supposing they were southerners like ourselves, consented. After we were joined by this small party, I noticed they looked at me in a very peculiar way. Whenever I would cry, hooray for Jeff Davis, hooray for this Southern Confederacy, hoorah! And it didn't help when she started singing ditties about John Brown's hanging, which were very popular in time. So she said, my father finally asked them who they were and where they came from. And one of the men said, my name is Solomon Brown, my mother who is with us is the widow of John Brown, who was murdered by the southerners after Harper's Ferry. And that's not bad enough. She says, next, one of the men in our party named Felix Wilkinson could hardly compete with himself for his cousin Alan Wilkinson had been killed by John Brown and his men in the border troubles in Kansas when the Northerners were trying to make Kansas a free state. There you have it, there's the reason. And honestly, I cannot imagine a more awkward moment. I mean, there's Solomon standing there and surrounded by the kinsfolk of this man whose murder he was involved with. And here's the kinsfolk facing the man involved in that murder. I mean, can you imagine what are the odds? And personally, if I were in the Salmon Shoots, I would have needed to change my underwear at that moment. But that explains why the Browns never identified. Even though they knew it was the Howards, they never identified them publicly because look how it cast them and the truth came out. It wasn't noble as they tried to say it was. It was they were involved in murdering a man in cold blood. So Solomon realized he needed to get the heck out of there fast. And his time, the opportunity came on Saturday afternoon when the wagon wheel fell off and everyone had to stop to make repairs. And Solomon believed that they would also then stop and stay there through Sunday. Sunday was normally a day of rest for a lot of wagon trains. They would rest, the animals could be fed, you know, rest and feed. They could make repairs and stuff. So he decided that he was going to continue over this little hill and when he was asked about by the Howards, he said, oh, you know, considering everything, I think I'm just going to, you know, separate myself a little bit. I'll be right over this hill. And they said, okay, fine. And Solomon wrote, he says, I knew that what I was proposing to do fit into their plans exactly. As they could come late at night, attack our little party, wipe us out and claim we had been killed by Indians. We went over the next rides and kept going, traveling with all speed. Instead of stopping over Sunday, the train hurried on after us. We made all possible speed for a week, pushing our teams as hard as they could travel. So this began the week-long slow speed pursuit. Because the option can only travel at like six miles per hour, so it was a slow speed pursuit. But they finally made the military camp at Camp Connor at Soda Springs, in Idaho, Turtwoy, with the Howards just a few hours behind them. So of course, when they get there, both groups are there. They both tell the soldiers a different story. And the soldiers have to sort it out one way the soldiers did. If anyone came west and had to pass through a fort or a camp, and the soldiers suspected that you were a Southern sympathizer, they would make you take the oath of allegiance to the federal government. If you refused to do it, you could be turned back. You could be refused settlement in the area. You could be detained. You could be imprisoned. Needless to say, the Browns immediately swore the oath. The Howards had a problem, but they did. As Nancy, the 14-year-old, said, the captain made all of our men line up and take the oath of allegiance. This was a bigger pill. It was difficult, but they did it so that they could continue on. Originally, the Howards had wanted to go to California, but they learned that California was suffering a drought at that time, so they thought, let's just head into Oregon. So their new destination was Portland, Oregon. The Browns continued to California, and they were given a military escort for 200 miles that brought them to the California Trail. Like I said, from the California Trail, they went down to Lassen Meadows and got onto the wagon road that led them straight to Red Bluff, and on October 30, 1864, they finally arrived. And it was mentioned in a tiny little article in the paper that a large immigrant trained from the east by the plains across arrived in town this four noon. Among the number was the wife and son and three daughters of John Brown, the year of Harper's buried notoriety. The Howards reached Portland the day before. The townspeople of Red Bluff gave the Browns dry goods, flowers, and groceries to help them get started in their new life in Red Bluff. So how was life for them? Well, Mary Brown became a nurse and a midwife. Annie and Sarah, who were teachers, they taught school and they taught at the little local colored school that was in existence at the time south of Red Bluff. And they also helped their mother with nursing functions. Solent, he worked clearing fields and shearing sheep for local ranchers and eventually he and Abby were able to buy a ranch where they began raising their sheep. In 1865, the newspaper in Red Bluff began to raise an idea that why don't we start a collection to build the widow Brown and her daughters a house. And this became a statewide collection effort. They were able to raise about $426 which amounts to about $8500 in today's dollars. And the people of Red Bluff built this little house which still stands at 135 Main Street in Red Bluff. It's two bedrooms and it was an 864 square feet. But by 1870, the Browns decided they were going to move. The reasons were the Valley Hing, local civil war tensions and the Red Bluff Sentinel newspaper whose editor was a staunch Southern Democrat and enjoyed harassing the Browns to no end by having articles that were detrimental about John Brown's memory, calling him a horse thief and a murderer, which wasn't too far from the truth, but it wasn't enough to annoy Salmon Brown who challenged him that, you know, that's the way it is. So normally this would be the end of the story. They moved to Humboldt County. But we go back to that post script from Abby. And she, in that post script, she mentioned that when Salmon met that Howard, he met him at Cottonwood Creek, which isn't Hingham County. It's a border between Shaston Hingham County. That meant the Howard's had come down from Oregon. And we're living in Hingham County, Red Bluff. So then that sent my research into a whole other area. It's like, all right, now I need to find out what happened to them. They've come down here and what they do here in Hingham County and North California. They have to do with being a Methodist lay preacher, Reverend Howard, again, who was the leader of the train. He came down here and he traveled the circuit through Shasta and Hingham County, and his son spent two years in Rillo's, California, in Glen County before being transferred back up to Oregon. Reverend Howard had a daughter, Sarah Jane, who married Butte County pioneer Pleasant Marion Glen. And they went on to have a family there. Their son opened up the first car dealership in 1904 in Chico. And then even Felix Wilkinson sawments and hadons on the Oregon Trail. He came down with the family and first he settled in Anderson. He worked there for a while. His mother, Nancy, who lived in Red Bluff, she passed away in 1871. And his stepfather took the family and moved after her death to Motaw County where they began ranching. There may still be some descendants there. I don't know yet. I haven't found any in my research yet. Felix drifts down and we find him in 1876 in San Francisco. He's taken the job as a lamp lighter. This is not Felix. This is a picture depicting what the flyers did. They lit the lamps in the evenings and then turned them off before dawn. And he did that for 16 years. He married. He had two children. And then after his death in 1894, he disappears from history. Nothing more is learned of him. But like I said, connections. I tried to see if there was any direct connections with this, the Browns of the Howards, with Nevada County. Couldn't find a direct connection, but could find a indirect connection that has to do, involves a lot of crap. In 1875, Lada commissioned and gifted a cast iron fountain that still stands in San Francisco, Air Market Street, where Ziery and Kearney Streets come together. Three years later, Felix, who's the lamp lighter, decides he wants to supplement his income. So he applies for and becomes, quote, a keeper of Lada's fountain, which paid an extra $10 a month, which is like a little over 300 in today's dollars. Not a direct connection, but it's an indirect connection. And it's like, oh, yay! Now, the Browns, what happened to them? Okay, in 1870, they moved to Rotaryville near Fortuna in Humboldt County. In 1881, Mary, along with her daughter Sarah Brown and her daughter Ellen and her husband moved down to Santa Clara County. In 1891, Salmon and his wife, Abby, moved up to Oregon, first to Salem, then to Portland, where they lived out the rest of their lives. And in 1960, at 1916, Salmon's grandson, Stephen Salmon Scott, which would be John Brown's great-grandson, settles in Chico, where I'm from. And he was a beekeeper there before his death in 1972. The Browns were also in Southern California. Jason Brown and Owen Brown. Owen Brown was both at the Potawatomi Creek Massacre, where he did kill one person. He was also at Harpers Ferry, but he managed to escape. Jason Brown never moved out of Potawatomi, and when he did, he was mortified. He was beyond horrified by what his brothers and his father did. And when he found out, he told his father that that was a wicked-looking thing that he did. But those two built a cabin on Ground Hill, which I believe is Brown Mountain in the same Gabriel Mountains, which overlooks Pasadena. And they lived there for a while. Owen died there. Jason later moved to Ben Lohman in Santa Clara County and then back to Ohio to end his life with family there. And the last connection I'd like to share with you is this daguerreotype. In the 1840s, this daguerreotype of John Brown, seen there was taken by African-American photographer Augustus Washington. In 1949, this daguerreotype was given to Daryl and Maxine Robinson as a wedding gift from Daryl's great-grandmother, Annie Brown, John Brown's daughter, who came across on the Orchid Trail. In 1996, Daryl and Maxine moved to Los Molinos from Humboldt County with the daguerreotype. Los Molinos is this tiny little blink of town. If you blink, you'll miss it on Highway 99 into Amon County. Tiny little things. In 2007, across the river in another tiny little town at the Hainan County Museum, they had an antique appraiser date. And this daguerreotype was brought and shown to Chico Appraiser Leigh Lane. And he said, literally, when he had it in his hands, his hands shook because he knew who it was and that this wasn't original and it was one of only six daguerreotypes known of John Brown. He helped verify it and he also helped facilitate its auction where it was sold for just under $98,000 to a museum in Kansas City, Kansas, the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, where it is today. I'd like to close with a quote from one of my favorite historians, Lee Roy DeHappen, where he says, research is detective work and it has all the fascination and thrill of a detective's pursuit of clues. How exciting to find a putative bit of information in some obscure library or collection. Some long sought fact that explains conditions or solves puzzles. Some of your name or report in a faded newspaper, a rare pamphlet, with significant information and research that takes the joys of discovery. I hope you've enjoyed this presentation and this sharing of the joys of discovery with me tonight. And I think this quote, I visit these girls' library archives today and I'm so impressed with it. And looking at all the documents that are there, the records that are there, I just think of someone somewhere just wondering, oh, if I only had this information and it could be there for life. It's amazing the treasure we have, value it. Personal experience with the Amon County Historical Society, our archive got decimated when it was moved to a new library and we had a new library that disbelieved the value of history. Most of it ended up in the garbage dump. So, that kills me. So, when I saw what you have, it was like walking into heaven. So, treasure it and support it, it's valuable. So, are there any questions? Yes? I might have a direct connection with a lot of country researchers. The Red Love Colored School. Yes. I believe the founder of that school was from an Amon County. I went up to Red Love. The one I'm thinking of, the school that people say they taught in was founded by Pleasant Logan, and who was in Chastok County came down. Yeah, I'd like to know. I know you had one of our early pioneers who actually honored a small school here, and then took the assault camp to look around. There was a school teacher. Oh, okay, yeah, I'd love to have that information. Yeah, I'd love to because I also, I'm a publication editor for the Historical Society's Little Memories, the annual book. So, yeah, that sounds like a fantastic story right there. Yeah, I appreciate that. Okay, any other questions? Could you, would this program have his portrait in 1840? I couldn't quite follow the stepping of who had it. Who thought I'd be a great granddaughter or a great teacher? Oh, okay, let's go back. Okay. Again, we'll talk about the photographer. Pleasant's Washington had, he was African American, he was born of slaves, but he was a pretty black who lived in, he was born in New Jersey, and he began taking daguerreotypes to fund his way to school. Then he opened up his own photography shop. He dropped out of school, and I don't know how or why, but he took six daguerreotypes of John Brown. There's one where John Brown is holding a flag, and it's a flag of a militant abolitionist, the underground railroad. It's the militant arm of them, which I never knew they had a militant arm, but they did. So, the daguerreotype was in Annie Brown's possession, John Brown's daughter. Okay, and so she brought, she apparently brought it across the trails and had it with her when they moved from red love to humble. Then apparently she was still old, I didn't do the math, but she was old enough to have given him, given her, let's see, great-grandson, the daguerreotype when he got married in 1949. So it just passed down? It passed down with them, yes. And then Daryl, the son and his wife, they forgot the daguerreotype. They moved to Los Molinos in 1996, and then in 2007, someone, I don't know who, because I don't know if Daryl or Maxine, that either one was alive at that time, maybe the family found it in their events, and it's like, well, let's see what this is all about. $98,000 later, they found out. So, it was passed down through the family, now it's in the museum, it's outside of family control. But, yes, that's how it got passed. Any other? I have one other question. The size of the military escort, I think it's the 200 miles. No, no, no, they escorted them 200 miles. 200 miles? 200 miles. It was led by, hopefully I have the information. It was, yeah, it was, it was under the command of Lieutenant Francis Marion Shoemaker. He has a connection, I found him in Buick County, mining for gold in 1950. And then he joined, he came down, maybe following the gold, I don't know, but in 1861, he's down in Calveras County, where he joins the military. But I think it was six men under his command, but they accompanied him, and it wasn't uncommon for military to escort wedding trains. They were like the modern-day California Army patrol. They would escort you through dangerous areas. They'd wholly traffic back. If there was a problem, you'd have to stop and wait until things cleared up. But they were afraid that the Howard's might try to do something, come down and try to harass them. Or Indians, you know. So it wasn't few men led by Shoemaker. So, 200 months. Any other questions?