Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

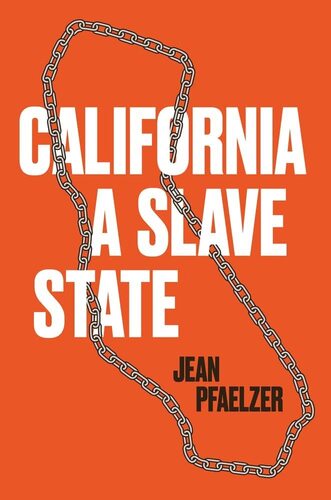

Video: 2024-02-08 - California, A Slave State with Jean Pfaelzer (84 minutes)

The untold history of slavery and resistance in California, from the Spanish missions, indentured Native American ranch hands, Indian boarding schools, Black miners, kidnapped Chinese prostitutes, and convict laborers to victims of modern trafficking.

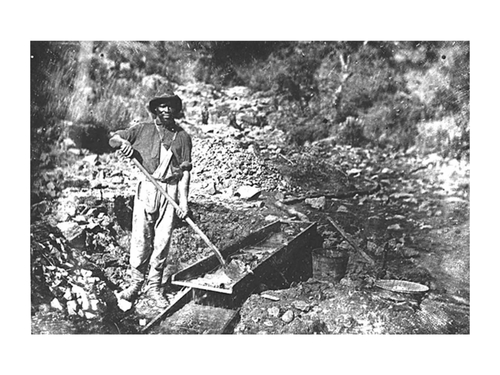

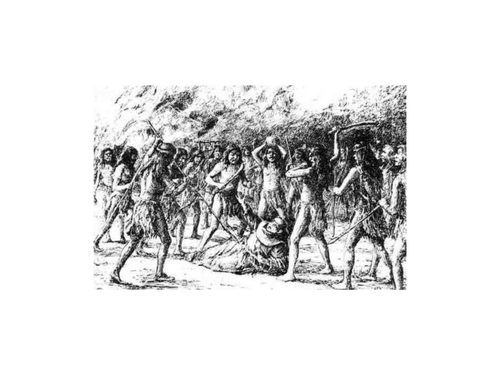

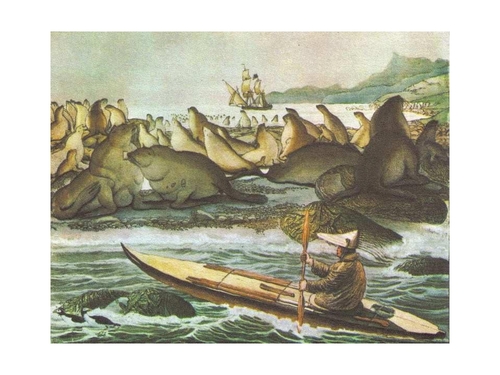

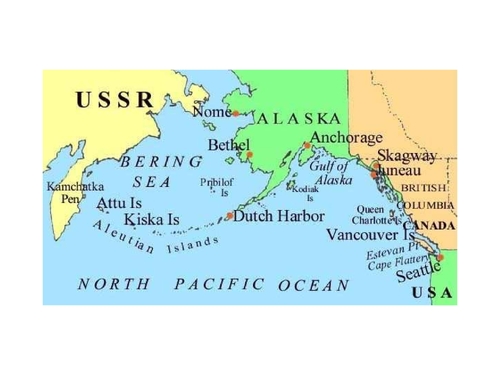

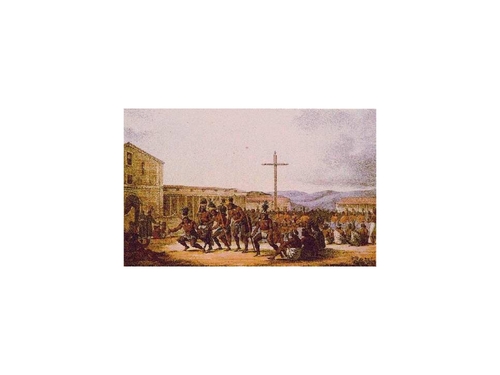

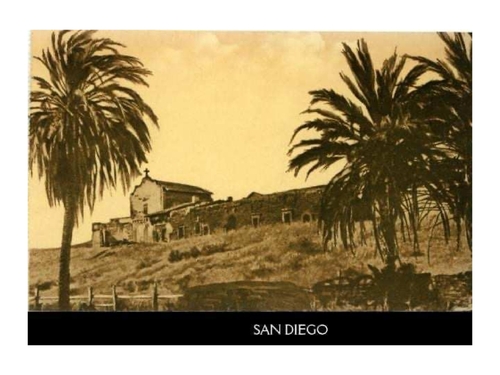

California owes its origins and sunny prosperity to slavery. Spanish invaders captured Indigenous people to build the chain of Catholic missions. Russian otter hunters shipped Alaska Natives—the first slaves transported into California—and launched a Pacific slave triangle to China. Plantation slaves were marched across the plains for the Gold Rush. San Quentin Prison incubated California’s carceral state. Kidnapped Chinese girls were sold in caged brothels in early San Francisco. Indian boarding schools supplied new farms and hotels with unfree child workers.

By looking west to California, Jean Pfaelzer upends our understanding of slavery as a North-South struggle and reveals how the enslaved in California fought, fled, and resisted human bondage. In unyielding research and vivid interviews, Pfaelzer exposes how California gorged on slavery, an appetite that persists today in a global trade in human beings lured by promises of jobs but who instead are imprisoned in sweatshops and remote marijuana grows, or sold as nannies and sex workers.

Slavery shreds California’s utopian brand, rewrites our understanding of the West, and redefines America’s uneasy paths to freedom.

California owes its origins and sunny prosperity to slavery. Spanish invaders captured Indigenous people to build the chain of Catholic missions. Russian otter hunters shipped Alaska Natives—the first slaves transported into California—and launched a Pacific slave triangle to China. Plantation slaves were marched across the plains for the Gold Rush. San Quentin Prison incubated California’s carceral state. Kidnapped Chinese girls were sold in caged brothels in early San Francisco. Indian boarding schools supplied new farms and hotels with unfree child workers.

By looking west to California, Jean Pfaelzer upends our understanding of slavery as a North-South struggle and reveals how the enslaved in California fought, fled, and resisted human bondage. In unyielding research and vivid interviews, Pfaelzer exposes how California gorged on slavery, an appetite that persists today in a global trade in human beings lured by promises of jobs but who instead are imprisoned in sweatshops and remote marijuana grows, or sold as nannies and sex workers.

Slavery shreds California’s utopian brand, rewrites our understanding of the West, and redefines America’s uneasy paths to freedom.

Author: Jean Pfaelzer

Published: 2024-02-08

Original Held At:

Published: 2024-02-08

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

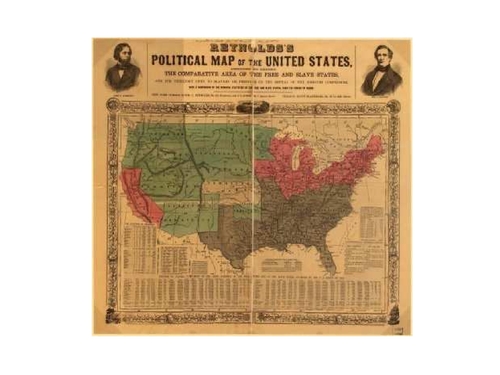

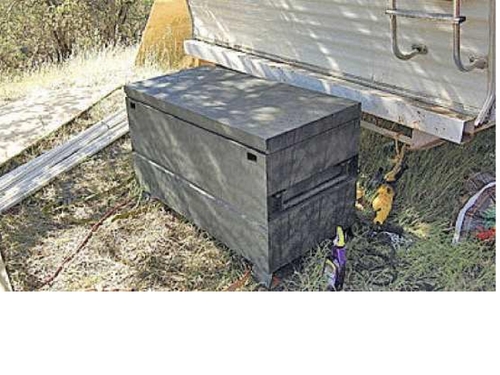

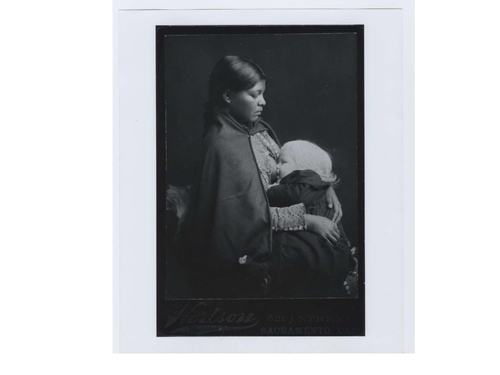

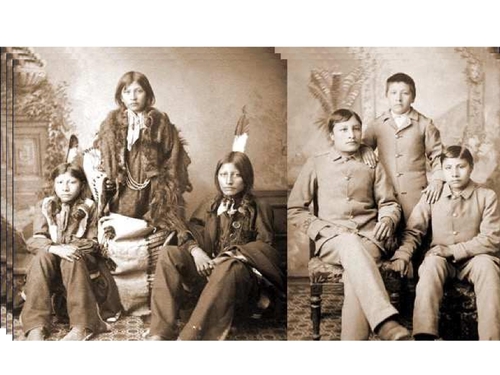

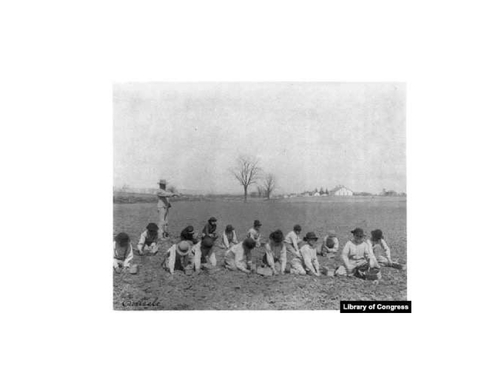

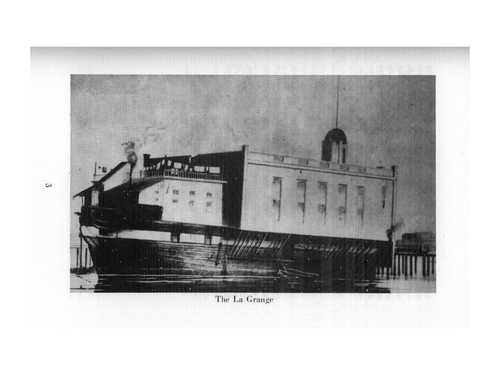

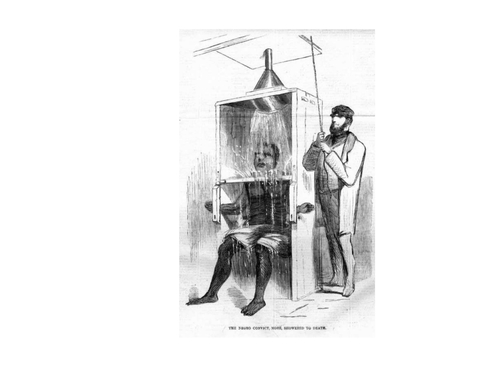

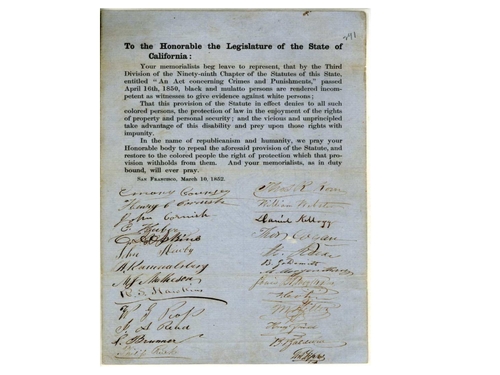

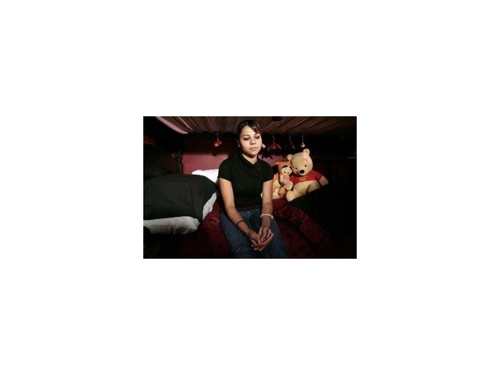

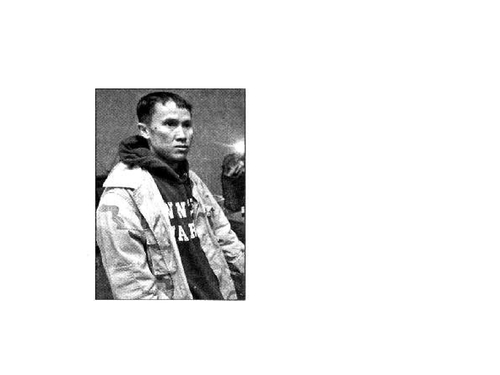

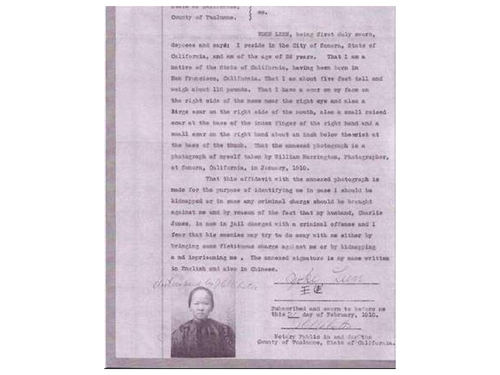

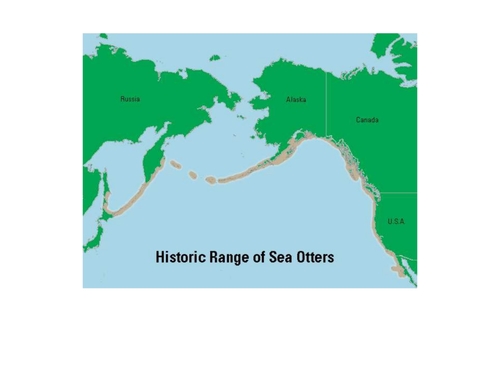

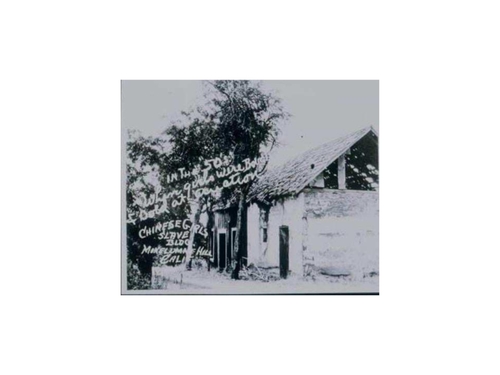

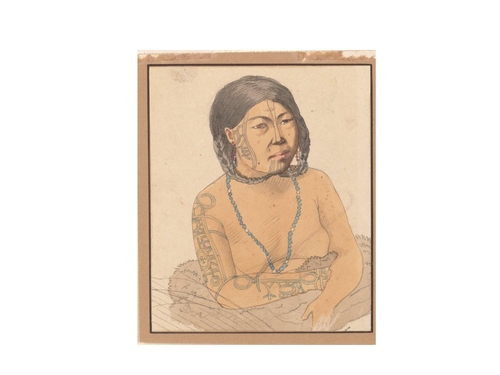

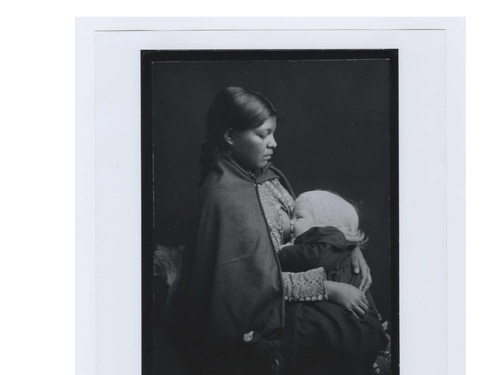

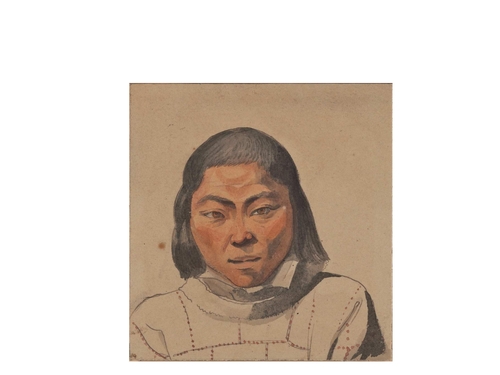

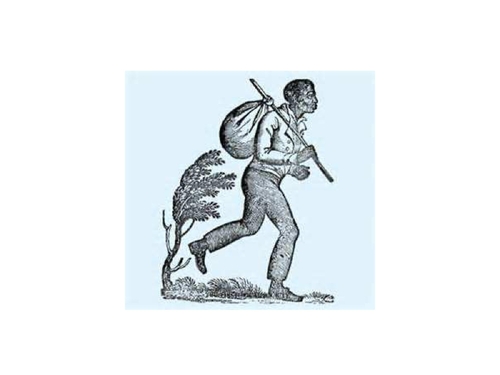

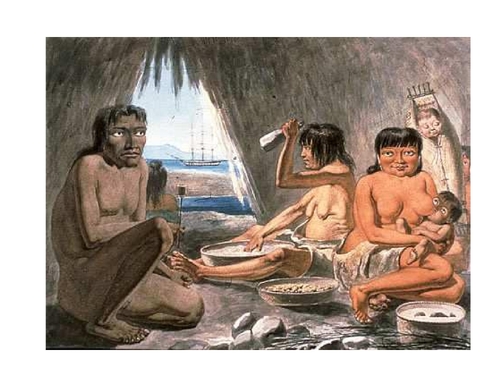

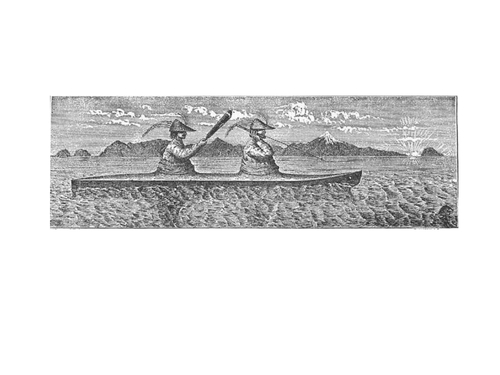

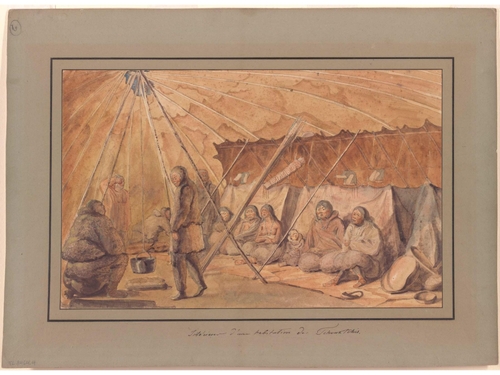

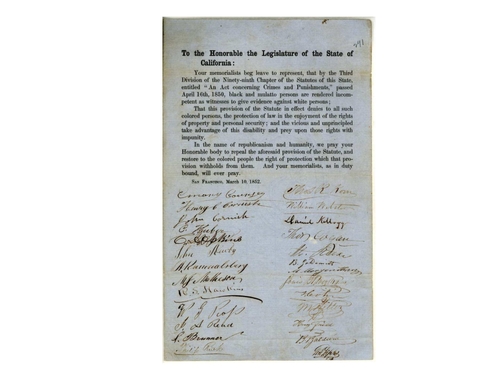

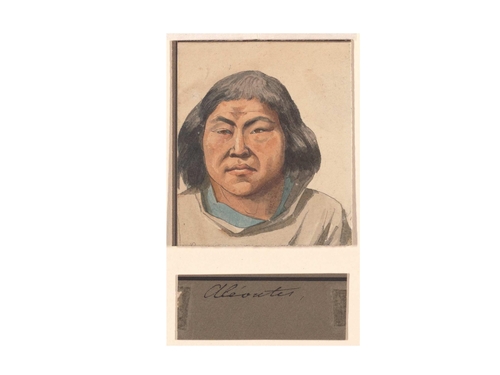

As I recall, Correct Play, I think it was Linda Jack about a year ago, it kind of taught me on this interesting speaker prospect. That's sometimes how far in advance we start working on these presenter arrangements. And I did pursue it and took a while talking to her publisher, and then eventually I got to chat directly with our presenter and excited to present tonight, Jeanie. But I'm going to ask Linda Jack to come up and talk about it. I can bring the microphone to you. Want to do that? Okay, I'll bring it to you. She's going to share this a bit more about our presenter tonight. Yeah. Thank you. Yeah, and there are some books at the back, so anybody should grab one. And it is my privilege, where is that? There she is. Tonight to introduce our speaker, Jean Felser, Professor of American Studies, English, Asian Studies, and Women and Gender Studies at the University of Delaware. Jean and her husband, Peter, have had a. . . Fels, did I say that? We're here tonight also. So we welcome them. They live in Washington, D. C. , so they've come a long way to be here. Jean received her PhD in English, American Literature, and American Studies at the University of London, and a graduate diploma in Literature and Society from University of Cambridge. She is a public historian, a teacher, author, speaker, commentator, and she has a very long list of credits in service, which you can find on her website. However, Jean has deep roots in California. She was born here and attended public schools, which included the University of California, Berkeley, where she received her BA and MA in English. And she and her family also have cabined up in Humboldt County, so they keep one foot in California. Tonight, Jean will talk to us about her latest book, California, a Slave State, which was published last year by Yale University Press. The book has received rain reviews. I'll share just a bit from Erin Aubrey Kaplan's review in the LA Times, just in case you think this might be a dry book. Believe me, I've got it, and it's not. So here's a little bit of a review. A devastatingly detailed, urgent, and somewhat regretful confirmation of an inconvenient truth. Far from being the place where everyone got an equal chance, California embraced slavery from the outset. That boosterish tale of California's endless possibility turns out to have been built with sweat, oppression, coercion, and genocide. It was precisely California's openness, the author posits that allowed greed, cruelty, and hypocrisy to run amok. And it is this bitter irony, not the orange grows, or a Mediterranean incline, an LA Times article after all. That makes us, that froth word, exceptional. So we are very fortunate that Jean has braved our latest atmospheric river to join us tonight, and please join me in welcoming Professor Jean Bellisic. [applause] Thank you. Can you hear me? Am I on? Yes. I love that LA Times review because it came early, and of course it's a huge relief to a writer to see that first review. But what I hope our minds go tonight, especially in this day and age, and in this week, is that the story of California, a slave state, is also the story of slave revolts, slave resistance, the endurance and the humanity of people, and the incredible creativity of a people under horrific stress to take charge of their lives and to find their equality, their education, their right to testify, their right to marry, their right to be with whoever they wanted, to have kids, and to thrive in California. I'm really interested in how the reviews have focused on the victim side of the story and not on the rebellious side of the story. I think I'm a rebel spirit, and I'm fascinated by people's attraction to only one side of the story. So tonight, I feel like I'm echoing. Am I echoing? [laughter] Listening to the story once will be great, twice. [laughter] Okay, is this better? Yeah. I don't even know what I mean. So as we talk tonight, and I'm fine with questions, and we'll take time afterwards to answer questions, and hopefully the chat with people, that I'm very concerned actually by the deep attraction to only one side of the story. And when people ask me, "How did I make it through writing this book?" I really, in moments of despair, and probably some of us have had a fair fit between the pandemic and the politics and the divisiveness, that this hasn't been an easy year, or an easy couple of years. And actually, I go into my book to see a really resilient, enduring, hopeful, musical, ambitious people who really intended to be part of California, and to thrive, and have families, and live in this incredible state under the most impossible conditions. So if there is a theme, it's the sort of the tension between hope and despair, and I think that may be a kind of knife-edge many of us are living on right now as that moment between hope and despair. So I just wanted to add that to the LA Times. The beginning of the year was amazing, and it turned out her husband is a teacher in my old high school, Hammeh High, Hamilton High in LA. So we had a great connection, but she very much focused on the challenges of this story. So I'm going to try tonight to talk through images and to talk through some slides, and I'm really happy to be back in Nevada City. My last book, Driven Out, The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans, a huge part of that book was written here. It had been in all the libraries and at Searls. So I'm really happy to be back, except I've gone one up to the store again, and I've transcended the best Western in my career. And to bring my husband for the first time to Nevada City. Peter, where are you? Here's my husband, Peter. Peter, welcome to the Madison. This is a very famous map. It's called the Reynolds Map, and it came out in about 1858, and it was the map upon which the Civil War was planned, mounted, and organized. And you can see that there's a lot wrong with this map. The gray areas, so this is 1858, we're headed right into the Civil War, and the gray areas are slave states, and the pink areas are free states, and the green areas are the territories, a lot of which we took from Mexico. We'll talk about that. But there's something wrong with this picture. California is too tiny, and the map is emphasizing the green territories, and that's what was on people's minds, was were all of these new lands that were coming into the United States going to be slave or free. And the contest of the Civil War was not only about the South, but the South very much planned to extend slavery out to the Pacific. And the question was, what was going to happen to the territories? And so this map is skewed toward the big question of, were the new states, the new territories, going to enter the Union as free states or slave states? This map tells one of the familiar stories of slavery in the United States. It's an African American story and a North South story. It does not include the slavery of Native Americans or Chinese migrants or Alaska natives who were transported down the coast by the Russians. So there were a series of iterations of slavery, and I'm going to kind of walk chronologically a bit through this tonight to try and pull this all together. But this is the traditional view of slavery. It's what we were taught in school. I went from primary school through Berkeley and had no idea. And I was unschooled with an amazing California education. I was unschooled about many aspects of our history. So this is the hidden history of slavery in California, the slave revolts, and the resistance. It also expands our idea of abolition, our idea of freedom, our idea of people's commitment to struggle for their freedom. And this map gets it wrong. But California was and is a slave state now, as we think about human trafficking coming into our state. At the airports along the border, human trafficking from foster care. Kids are sold out of foster care. Kids are being kidnapped from detention centers. And I want to talk about how to lead up to this very fractious moment. And for those of us who are parents, we think and we guard our kids and the population of our students, because our kids are in precarious situations and immigrants are in precarious situations of how they come into our country. So this is one thread of this story. And I learned a lot in writing this book. This is more technology than I'll discover. Why did I write this book? A few things can help me to tussle with this question. One was an article that came out of the "U. R. Standard," the main humble county newspaper. And it was a story of a 15-year-old girl who was homeless, a runaway in Hollywood. She was wandering the streets, and she gets picked up by a couple of guys who seduce her into their car, and they drive her up to the marijuana groves up in Lake County, and they put her in this crate. And this 15-year-old girl is locked in a crate, and they drill these two holes in the crate. One was for air, and the other was to hose her down. And they would let her out to trim the marijuana groves and to sexually service the field workers and these two men who owned the grove. And I read this story right before Christmas, and it was like this didn't square with the state that I love or my commitment to my students, my commitment to my kids, to young people. And to my daughters. And I was horrified by this story. And so that was one of the issues, like how is this happening in the state that I know, and this beautiful county of Humboldt with the Six Rivers and the Redwood Trees, that I love where I go to read and to hike and to be quiet. And it was such a terrifying and unsettling story that I had to find out about this girl. As it turns out, and this is the other part of my story, is that one day her owners, her traffickers, drove her down to Sacramento to go shopping. And they lock her in a motel room. They go out to shop. She sees a telephone. She picks up the phone, dials 911. The cops come and she frees herself. And she was not able, after eight months of that, to testify that the guys are convicted. They go to jail. They spent the evidence. And she is free, and of course a very vexed and troubled girl. And it was that story that drove me into almost working backwards in time to figure out how did this happen to this girl. And also, how did this 15-year-old have the moxie to know exactly what to do to free herself and to do that. The story begins in 1769 with the invasion of the Spanish to build a chain of missions. But because of the presence, and Linda has found out so much more about the presence of enslaved people in the mines up here, we decided I'd start the story with the African Americans. Gold, as we all know, was discovered in 1848. And the Union, the United States, really wanted California to join the Union. There was, if you remember from your old SAT exams or your high school exams, there was that Missouri compromise where a state, one state would enter enslaved, one state would enter free. It would balance each other out. There was no state to pair with California. But California was shipping $1. 5 billion of gold east to the government, to the bank, right away in the gold rush. There was no way the United States wasn't going to live there. California is the state very, very quickly. And they hold a convention. And California is instructed, assumed that it will write the Freedom Constitution. And people gathered in Monterey, some of you may have been there at the old customs house in Monterey, and they write this Constitution. Many of the people, and the people cheering California's Constitution to write this Freedom Constitution were slaveholders. I didn't know that slaveholders from the south had marched, walked enslaved Africans across the plains to work for them in the gold rush. And these are the people who were writing the California Constitution with the intention, under the direction that this is going to be a free state. And they write into the Constitution, "Slavery will never be tolerated in California. " Sounds good, but tolerate is not a legal standard. It is nothing that you can take to court. And so they write this loophole into the Constitution. It takes the Senate almost a year to agree to this deal. And California, because they wanted that money, it meant California, with this kind of shoddy Constitution with this big loophole written into it, California didn't mean it. It never meant with the Constitutional Convention being written in Monterey that writes its out into its Constitution. The Missouri Compromise was a trisecta. There were three parts of the Missouri Compromise. The first was California would enter the country as a free state. The second was Utah and Nebraska would be free to choose. That wasn't part of the original balance. That wasn't the deal. But they could choose whether to enter the country free or enslaved. The third, which was consistently dangerous, like folks such as an enslaved minor, said that Congress agreed to pass the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. It's one of the worst pieces of legislation in U. S. history because it meant that any black person, especially in the North, but any free black, could be snagged and taken back into slavery, or taken into slavery in the South, and could be declared a fugitive from labor, with how the law was written, a fugitive from slavery. What happens then is that you've got plantation owners bringing enslaved blacks out to California. They marched across the plains. They marched because they were in charge of the oxen. The enslaved people who were brought to California have a lot of skills that they learned on the plantation economy. One of them was animal husbandry, and they were in charge of the oxen and the horses that were coming across in special wagon trains that were designated okay to bring slaves in these wagon trains across the plains. So the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 says that any black person in the North could be targeted and named to run away, seized, and sold back into slavery. It was very dangerous, and it encourages free blacks to come to California. Free blacks wanted to come to California for the same reason people, hundreds of thousands of people, were coming from all over the world for gold, for adventure. They were mainly men. Many of them, like from Argentina and Mexico and China, were skilled miners, and they freely choose to come to California to pan for gold. Free blacks want to come out for the same reason for adventure, but also they had at their back the Fugitive Slave Act. They had to get away from the East Coast and the North. Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist, said, "You guys can't go. We're in the middle of the struggle for abolition. If you flee now, you're going to, you know, really disrupt, disrupt the struggle for freedom of enslaved people. " And they say, "Fred, we gotta go. You know, we've got the Fugitive Slave Act at our back. " And he cuts a deal with some of the young black abolitionist leaders, people I've never heard of, a guy named Miss Lynn Wisker Gibbs, Peter Lester, his wife, that if they travel with Douglass for the summer, he's going to train them to be speakers, organizes writers in abolition, and then they can go to California with his blessing. And that's what happens. He travels with people. They have all the nightmares who think what happened. Churches where they're going to speak are burdened down. And they learn how to be abolitionists and how to write and how to be persuasive in the struggle for freedom. And they go to California, what they don't expect to find are enslaved blacks in California, like in the minds above here that Linda is doing this amazing research on. So there's this surprising encounter in California where free blacks meet enslaved blacks, and the free blacks now know how to do this, and they free enslaved blacks. If the voters are going belly up, they snag them off of boats as they're being shipped back to Orleans. They win through them the right to testify. Blacks, free blacks in California, hold three what they call "colored conventions. " I've never heard of colored conventions before. All over the country, thousands upon thousands of black people are gathering to meet in colored conventions to demand a right for freedom. What they want here in California, and I keep looking for the word "freedoms" in the minutes, they want the right to testify. Because if you were a free black and you couldn't enter into evidence, if you couldn't testify that you were free, you were subject to being enslaved. And so the whole movement of free blacks in California is for the right to testify. And that's what that guy who has no name, and I think the fact that we don't know his name, is really almost as important as I can tell you what his name was. Actually, this picture we believe was taken to the harbor down the road. People kind of doubt, like really? It was California's slave state. And this is an ad for the sale of a Negro, and it was in the San Francisco Herald. And I believe it was 1858, and it's an ad to sell a black person at auction in California. This is the kind of thing I would have thought I would have felt saying a New Orleans newspaper. I didn't expect to come upon it in a California newspaper. I would sell a public auction in Negro land, he having agreed to be set sail in preference to being sent home. Right, and it's an ad for a sale of a human being. Many slave owners of African Americans in California get out here for the gold rush, and they don't like it. They're up to here in mud and muck, as people who live up here would well know, and they're not making it. The plaster gold is collected very quickly. Hydraulic mining hasn't really come on the scene yet. And the way they make money off of enslaved African Americans is to rent them out. There was a huge business in California of renting out enslaved blacks, and that's where the money came in. Many slave holders actually leave enslaved people here to the south, and we'll talk more about this. People, black people, did not come out to California to flee. There was not yet, but there was going to be an underground railroad in California, and it went from the Bay Area up through Sacramento. There was a black boarding house called the Hackett House, where black people were hidden and protected, and then they were sent on. There was a mass exodus of 800 black people over a three-week period in 1858 to go to Canada. They were welcomed and wanted in Canada. In British Columbia, British Columbia is going to have a vote, whether it's going to go to Britain or the United States. British Columbia had a mulatto governor, a guy named Douglas, and Douglas wants the vote, because he knows that Britain has freed slaves, that abolition has happened. He really wants British Columbia, now British Columbia took Britain, and he invites black people from California to come to settle in Vancouver, and 800 people in a three-week surge migrate to Vancouver for their freedom. This is a global story as well in this fight for freedom. One of the people who intrigues me the most is a guy named George Demas. George Demas is the son of a slaveholder named George Demas, so obviously dad George Demas, father, son, George Demas, with the right to rape the mother of George Demas. George Demas doesn't come across the plains. They sail down the coast of the United States, and they sail down as far as Panama. Of course, there's no Panama Canal. And George Demas, enslaved, carries his owner's canvas gambling tent up and over the jungles of Panama, across the Chaga River, down to the other side, and on the Pacific side, they wait, along with thousands of miners, for a boat to carry them up to San Francisco. George Demas carries this wet, heavy, old canvas gambling tent, and they set it up in Coorsen Square, which is right at the edge of Chinatown in San Francisco. And George Demas works as a porter, having carriage swept this thing across Panama. And he picks up the droppings from the gambling tent, the dime to the quarters, and he buys his freedom, from his own father, from dad, George Demas. And he buys his freedom, and he stays, and he does it again, and he buys his mother's freedom, brings her out from the south, and the two of them set up a competing gambling tent. And then he comes down to the richest blacks in California, and they build hotels and boarding houses, and they donate their money to the cause of abolition and the cause of freedom in California. So a long way from carrying through the jungles of Panama, I'm just picturing this wet, heavy canvas, gambling tent, and the freedom that he bought for himself and his mom. Okay, well, now take a trip back in time to the missions. 1769, by Junipera Serra, crosses the border at San Diego, and it's by land and by sea, it sounds like Paul Revere, but it's Junipera Serra, that there are three ships and a land invasion at San Diego, right at the border, right where the detention centers are now, just to keep the balance between the present and the past in our minds. And they cross the border, and they are carrying with them two pieces of paper. One is a papal bull, an order from the Pope to convert the Indians of California to the Franciscan breed of Catholicism, and the other is an order from the Spanish emperor to conquer California by building this chain of 21 missions. And what the Spanish want out of the deal, what the Pope wants is conversion. We are this tiny, weird, northern, you know, little teeny corner of the Spanish empire that's going down to Ecuador and Mexico and Peru, and there they have enslaved the native people, the indigenous people, to work mainly in the silver mines. They needed to feed all these people. They didn't want to release the Indians from the mines to take the time to grow food, so the plan was that these missions would actually be plantations that would feed the rest of the empire in Peru and Mexico. So they knew exactly how to do this. There was a chain of missions in Baja, California, and they were going to build and do build 21 missions from San Diego. It was supposed to stop in San Francisco, but the Russians are coming, we'll tell you that story, and they had two more missions in San Rafael and in Solana to block the Russians who were coming from the north. So this is one of the early photographs. So you get the camera, what, around 1845. So this is not a 1769 photograph, but this is very much what the missions looked like. It didn't look like our kids' fourth grade mission projects that they were going to do anymore, where the kids built, I mashed up acorns, and then they said, "You don't want to eat those because they're full of acid and they're nasty. " We live in D. C. , so Peter, actually, was supposed to be our kids, but he had to build a Supreme Court out of sugar cubes, but California kids built missions out of sugar cubes. I don't know what we would have done without sugar cubes, but they didn't look like this, and they didn't look like Taco Bell. This is very much what the missions looked like. So you get eight fanatical priests, a hundred soldiers, half of whom died getting here, and the Indians in San Diego, the Cuneyay tribe, are watching. They're supposed to be the first converts. What they're seeing is dead soldiers carrying off these ships. They didn't survive the trip from Mexico. Not a good argument for conversion. The 60 dead soldiers carried off the ships. What gets so persuasive? The first mission is built in San Diego. It was really a hut. The cathedral was shacks, and the soldiers, who were supposed to guard them, say, "You go up on the mesas to build your cathedral. " They wanted nothing to do with this mission plan. They were low-level soldiers, and the idea of going up, but nowhere, into all to California, to build these missions, there was not going to be any silver coming out of the mines, not any payoffs. There were no women. One of Spain's plans was that for the soldiers to marry indigenous people, and in an early idea of eugenics, they were going to create this new breed of white Spaniards in Southern California. It didn't work. The first slavery hole in California was in San Diego. The Cuneyay natives have been captured to work in the missions, to build the cathedral, to build the barracks. Along with the soldiers, who could have cared less, this was such a low-level, non-profitable assignment, and that's why they said, "You go seven miles inland to build your cathedral. " The Cuneyay, who lived in the mesas up in eastern San Diego County, if you've been there, and they live along Pacific Bay, Mission Bay, where you can get a waitress and roller skates still. This is where the Cuneyay lived, and they organized. In 1775, just within a few years of the mission being built, the Cuneyay organized a revolt, and they built new arrows, new bows, and they encircled the mission, Mission San Diego, and they burned it to the ground, and they slaughtered Father Jaime, who was the head priest of the mission. This was in the grave, and done several years after the fact, of the killing of Father Jaime, and the burning of the mission, and freeing the Cuneyay people, never to return to the mission culture. This is, of course, a tourism mission. This is what California promotes. The missions are still a huge tourist attraction, and people go to the missions. We went very recently to the mission Dolores in San Francisco, which is a beautiful place. When I taught at UC San Diego, I went to Quinceaños, had baptisms and weddings at the San Diego mission. Of course, without rebuild, I had no idea that that was mission number two or three. I was never taught what happened to mission number one. This is founded in 1769. It didn't look so good. That was not technically colored. The Russians are coming from the north. You've never heard about this. Have any of you been to Fort Ross in Florida? We used to take a lot of the wines, farindo bread and cheese, go to Fort Ross and have this incredible view. It's right in Badega Bay, in Salahama County. What I didn't know is that in about 1745, Bering, like the Bering Straits, Bering is sent out by the Russian emperor to find the route to China. Everybody's looking for a route to China. He gets lost in the fog, and he turns around, and he sails back, no route to China, crashes on the rocks on this chain of islands, the Aleutian Islands that lead up toward Kodiak Island from southern Russia, and Bering crashes on the rocks. Bering dies, and the soldiers spend this horrific winter on the rocks. The snow doesn't melt till May, but what they've done during that winter is discovered the sea otter. The sea otter saves the Russian empire, and the sea otter is the softest, sochiest mammal in the world. That's what I believe. They have a million hares per square inch. The Russians have already decimated the Sable and the Mink in Siberia. All of a sudden now they've got the sea otter, and Bering's sailors, the ones who survive, go back with a thousand pelts of sea otter, and they're settled for, at the time, $3,500 each. Crazy, crazy money. It's the sea otter that's going to save the Russian empire, and they are going to invest big in the sea otter chain, and they formed something called the Russian-American Company, and first privateers and then Russian-designated sailors cross the Bering Straits and walk through the Aleutian island, capturing the Alaska natives, and they are the only ones that know how to hunt the sea otter. They have their kayaks, and the kayaks are actually made out of hair on the skin, and the women sew the most amazing waterproof costumes that remain out of the guts of a seal. Like, REI had nothing on what these folks could do, and the women would sew these with needles made out of whale bones or seal bones and tendons, and it was tightly waterproofed, and they had, like they knew that the helmets were like protection for that sunscreen, and they could see the sea otters. Here they're actually sealed, and that is a really interesting picture. The image of the empire, the sailboat, is right at the back. It's kind of, for those of you who are interested in photography or art history, it's really controlling your vision to see that, that Russian ship, and the Russian-American company says to the Alaska natives, the Supiac, the Denina, "You can take 50% of the Alaska native men for five years. " This was a very gendered economy. The women dug the roots, the kamma, like chamomiles, which they were boiled, and prepared the food, and built the kayaks and stitched the waterproof clothing in the men with the hundreds. And when the men disappeared for five years, the people starved. The women were assaulted. There was a tax. You could buy your woman back for a certain number of sea otter pelts. And the sea otters are sold in China. So if you picture these old images of Chinese men, Mandarin men, you know, the fur collars, and the fur around the bottom, and the fur muffs, that's sea otter. And when they killed off the population and decimated the sea otter trade, they turned right, they go down the coast, they skip over Oregon, what would become Oregon and Washington State, because the Tlingit Indians are there, they wouldn't have it. And so the first place that the Russians land, is that my cabin in Hummel County, in Trinidad Bay, is the first place that they start to hunt the sea otters, and they move on down, and they go as far south as San Francisco, where they run into the Spanish missions, who are coming from the 21 missions of Camino de Real, the path of the missions, and they run into the Spanish, and there they stop in the de Guebe, and they build Fort Ross. So this beautiful place, I would go with my sourdough bread, and my cheese, and my wine when I was at Berkeley, was a myth. In fact, Putin, let's not forget Putin, Putin believes that he owns this few acres of California, and there's this amazing article in Forbes magazine about what Putin does, because when Fort Ross runs out of money, this is really weird, but it's Forbes, but this is not one of my favorite progressive little magazines, but Forbes magazine says that when Fort Ross runs out of money, Putin has in the rich carl in Paris a collection of impressionist paintings. Fort Ross runs out of money, Putin sells an impressionist painting, and the money goes to Fort Ross. It's like I'm reading this thinking like, you know, I mean historians find candy stuff, but that was, that's pretty bizarre, that F. U. really believes that he is invested still in Fort Ross. So so much for my sourdough bread. So this has been the image. There are many, the way that some explorers would travel, like you see the photographs that made Americans that explored, that traveled with the photograph in the 1840s, 1850s, the Russians traveled with watercolorists, and we have these beautiful, beautiful watercolors of Fort Ross and of the Alaska natives. And someday if I want money, I'll do a cocktail, table filter, those watercolors. This is probably the most vexed image in California, a slave state. California's very, very first law, very first law, it's passed even before California is admitted to the Union, is an act called the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of the Indian. What the 1850 Indian Act did was legalize the forest, kidnap and sale of Native Americans. This is the exact time of what historian Ben Adley has written in American Genocide, where people from the East wanted California land, and the American military attacks Native American communities all over California. They torch the villages, they slaughter the men, and the women and children are on the run. And so this act for the government and protection of the Indian is to legalize the sale, mainly but not only, of women and kids, Native American women and kids, for domestic work, because there weren't domestic workers here, there weren't white women here, yet there were a few, you know, we've heroized them. But mainly it was for domestic labor and for companionship and for sex. This is one of the harshest images I found it in the basement of the library in Yale, at the Minaki Library, and this is a nanny, an Indian nanny who was captured. She had probably dressed in clothes at the photographer's studio. Now, it's hard to see that this is a studio. Who would take this girl, who's quite young, and nursing, we're an interracial family, and our daughter says, "This is the whitest baby she's ever seen. " And this is not, it's a parody of the Madonna and child. This is not a tender image of breastfeeding and nursing a baby that you adore. This is her forced labor, and one of the things that happened is that girls were sold to be wet nurses for white babies, and that's what this girl is. And I believe, because I've asked a lot of tribal people, this image, this photograph was taken in Sacramento, who would pose, who would take a girl into a photography studio and pose, make this very vexed and troubled pose? But that's what the 1850 Act for the Protection and Government of the Issue achieved. The other source of enslaved people were Chinese girls. Chinese men came to Nevada City, and all over the old rush country freely. They chose to come like men from all over the world chose to come. But it's a gendered story. The women did not choose to come. Young Chinese girls were kidnapped from huandong, hantong. The port cities of China transported generally through San Francisco. They were strip searched and sold at the docks of San Francisco, and then they were put into locked brothels on Jackson Street, which leads now into Grand Avenue. I will not say Grand Avenue, USA. And there are locked brothels. This girl served 20 men a day. We cannot imagine that much sex. That much sold for sex. It's unimaginable. And there was a curtain. The curtain would be opened. She would solicit a man. She was forced to solicit a man. And she would service him. The man, her owner, who was the wife of a Chinese merchant, would collect money, draw a curtain, and she would service another man again. And there are pictures in San Francisco. There are actually quite a few of these caged brothels along Jackson Street in San Francisco. And this is one. And as a mom of two daughters, I look at her a lot. I look at her a lot. And I can't begin to picture her life. A lot of these girls managed to run away. Some of their customers would fall in love with them or they wanted these women for themselves, either for companionship, for marriage, to start families, or to start brothels all through the gold country. And there are--I have pictures there in the book of some of these brothels in the gold country where the girls were sold. And as the girls ran away and found their freedom, by the 1880s, when you get the Chinese Exclusion Acts, the Immigration Acts, to deport the Chinese, the girls were in a very precarious situation because if they were deported, they'd be deported from San Francisco where they had fled. It would be like a black person being returned to New Orleans in our bond. So the girls were in a hugely--the ones who managed to get away and live and survive, mainly syphilis and assault and brutality. And if they ran away and came up here, or came up to Humboldt County, and there were fires that burned down Chinatown, or like in Eureka, a 24-hour purge. And that's the book I did up here in Nevada County, where they ran out, forgot the origins, Chinese-Americans. That's that story of the roundups and the purges and the people who got away. The other form of slavery in California, or another form of slavery in California, were the Indian boarding schools. And right now, because of Canada releasing the reports on the Indian boarding schools from the Canadian Supreme Court on the boarding schools in Canada, the board has traveled here, and there's much more information coming out about our Native American boarding schools. There was a law that Native American kids were required to have an education. But of course, there were not schools on all their reservations. The reservations in California were very small. They were very remote. They couldn't support a school. And religious organizations and government organizations started 12 Indian boarding schools in California. The pictures I have are from Sherman boarding school. It's still going. Sherman now has totally changed. It's like an HPCU. It's a very attractive place for Native Americans to send their kids because it has an athletic focus and it gets their kids into college and they get their decent education. What happened at the Indian boarding schools was something called the outing program. And every one of the boarding schools, the Indian boarding schools in California, had an outing matron. And of course, when I first heard outing, I was thinking how we use the word outing now. Didn't mean that. And these were the matrons that sent these kids out to work unpaid, unfree, uneducated, from the boarding schools to work enslaved in the Orange Grove in Riverside, which is where Sherman is, in the Lemon Grove, the Orange Grove. Eventually, there had been grapefruit, but not right away. And the present day, one, when the kids were forced to take off their Native clothing-- this is actually a picture from Carlisle in Pennsylvania. Maybe that's what he's read about. But it was all the same. They had to take off their Native clothing and wear white clothing, have their hair cut. They weren't allowed to speak their Native language. And if they write about--and there are a lot of diaries and a lot of letters--they write about-- they weren't allowed to talk to their siblings, and they couldn't speak in their own languages. But the most painful was to be separated from their SIDS. So this is the same-day photo of the before and after of-- and they talk about how scratchy the woolen clothing was compared to their Native clothing. This is a classroom. This is training girls to work as servants. So it's teaching the girls how to iron. This was the education. The California--this is down in Sherman in Riverside. This is the education we were giving to the Indian kids who were forced to come here--to come to Sherman-- to get an education. The education the government required them to get. And this was the education they got. The girls were really vulnerable. The boys went into the fields. They had each other. But the girls were sent one, two, into a household where they were men. And they were very vulnerable, and there was no protection or supervision. And of course, there was no pay. That's part of the definition of slavery, is unpaid labor, no ownership of your own body, no ownership of your sexual or reproductive body, no choice of what labor you wanted to do, no freedom to quit a job and try to find another job. A lot of forced mobility. Enslaved people are rarely enslaved where they're from. Somebody would protect them. It doesn't make sense. You have to move an enslaved person away from where they'll find comfort or safety. So these are the girls at Sherman around Riverside getting an education. This is also--this is the Library of Congress photograph. These are children working in the fields at Sherman School in Riverside. This was the education for the young kids at Sherman. This is a very painful image of the children dressed in western clothing. They're numbered, and I mean, it's written on the photograph, and of course the horrific photograph of the fourth little girl from the right. I mean, these are terrified and depressed children who were sent out to labor at a young age. And this is also from Riverside. Whoops. So one of the other forms of enslavement in California-- when I talk about resistance, the resistance from these kids was not as overt as say the Kumeyaay, freeing their whole people. There are letters where two girls would climb a tree and sit up in the tree and talk to each other in their native language where they couldn't be heard. There's a story of a girl looking out the window. She's depressed. She's terrified. She gets sick early on at her time in Riverside. And she looks out the window, and from the infirmary-- and she thinks she sees an arrow carved into the mountain. And she follows-- she escapes, and she follows this arrow after her tribe at the foot of the mountains to find her freedom. And a lot of the kids ran away. A lot of the archives at National Archives are from the parents demanding their kids back. And my kids are not getting an education. My kids are not safe. And these were not literate parents. Someone else is writing this, often writing the letters for them to the school. And Sherman, to my surprise, has kept these archives. These are really damning letters written to the school saying, I want my kid back, and you're abusing my kid. And there are stories of when the recruiters would come to the tribes to gather up these kids, of the women hiding in the woods with their kids until the recruiters would leave. So there was always resistance. People tried to keep their kids free. Another form of enslavement in California was convict labor. There are only-- the 13th Amendment to the Constitution says, end slavery. There will be no more slavery in the United States, except as punishment for a crime. But slavery is not punishment for shoplifting or petty theft. It's not a suitable punishment for really any crime. And California in the Gold Rush did lousy good money. Everybody's got money. But things were really expensive. A loaf of bread cost $12. A jug of milk cost $18. Nobody had that kind of money. And there was a lot of petty theft, a lot of unemployment. And people wanted laborers. And the California legislature gives this corrupt contractor, his name is James Edsel, $100,000 to build Sam Quentin Prison and control a crime. But the crime, for the most part, was theft, petty crime, survival crime. And what happens is that Edsel takes this $100,000 and he buys old ships. In San Francisco Bay, there are 400 ships floating in the bay that had brought gold miners out. And then the captives and the sailors go, there's a lot more money in the Gold Rush than in shipping these men out to California. And they abandoned 400 ships in San Francisco Bay. And Edsel buys up three of these ships and turns them into prison rigs. And he sails them around the bay. And he's renting out California prisoners to build the mansions in San Francisco. They build the streets in San Francisco. And they're sleeping in these prison grids where he's built cells under the decks. The guards didn't even want to go under the decks because they were so foul down there. And finally the legislatures build the damn prison. And after several years, the prisoners built their own prison at San Quentin out of a rock quarry that Edsel has bought for himself in Marin County. There should not have been San Quentin prison in Marin County if it weren't for the rock quarries, because it's not an island. Alcatraz made much more sense than San Quentin because it's very easy for people to leave a rowboat and escape, and they did. This is the LaGrange. It was a prison ship that was sickled at the Delta from San Francisco Bay. And that's a prison that was built and kept outside of Sacramento. And finally, Edsel builds the prison. And inside the prison, he builds factories. And he rents out his conflicts to private industry to build doors, to build furniture, and mainly to build a jute factory. California agriculture starts with wheat, and wheat flies around, so it has to be bagged up, tied up. And it was shipped in jute or burlap bags. Then the jute comes from India. It's shipped from Calcutta. So this is a global story. And San Quentin buys up the jute, and they have a mill in the basement of San Quentin prison. And the prisoners are forced to weave these jute bags. There are pictures of the factories in the books. I'm running out of time here. But if you--it was a 12-hour shift. You had to stand for 12 hours, weaving these burlap bags out of lume, and you couldn't talk. There is no--well, I couldn't go 12 hours without talking. Anyhow, but I certainly couldn't stand a lume without sitting down for 12 hours. And if you talked, you were tortured. So there were two prison systems in the United States, the Auburn system that came out of New York and the Quaker or Pennsylvania system that came out of Pennsylvania. And they all wanted the idea that if you were putting solitary confinement, you would meditate your way out of crime. And of course, there wasn't space for solitary confinement in the prisons because they wanted as many convicts as possible to do this labor. But this is an image of the Negro convict shallered to death. And this was waterboarding. It was an early form of waterboarding. And this was in the San Quentin prison system as punishment for talking while you were standing and you were supposed to be weaving burlap bags. Women are not supposed to cry at work. And there were a few moments where I cried a lot in writing this book. In Sacramento at the archives are 8,000 petitions submitted by African Americans for the right to testify. And when I went into the archives in Sacramento and I started going through and touching, and I'm so glad that everything up here is going online, but there is something about handling these pieces of paper that makes it very real. And these were 8,000 petitions organized by the Colored Convention by African Americans, free blacks in California, who gathered petitions for the right to testify so they can enter into the court system that they are free. The last thing I want to talk about is human trafficking. And this is one of the ways that healthcare workers, police officers, medical workers, childcare workers, teachers can know that somebody is being trafficked, is they're being branded now. And one of them is with barcodes. And another are certain, and I think these things will change over time, but if a healthcare worker sees a tattoo of a crown, that means that she is under the rule of someone else. So people who are working in the human trafficking field are trying to train police officers, healthcare workers, nurses, and medics to look for tattoos that are certain kinds of brands. Obviously this one is pretty clear that this is somebody who is for sale. I had the opportunity to work closely and spend a lot of time with a woman in Humboldt who had been trafficked, she was trafficked for 8 months. She was lonely, abused, she was an older teenager, she was working with the Sbarros in Eureka, and a guy comes in, there are books on sale at Amazon on how to be a trafficker. One of them is called "Chemology. " I actually bought a few of these because my library didn't carry them. And it's training on how to be a trafficker. And the first, and it's take your time, it takes 6 months, get the girl to trust you and to become a dad figure, listen to her stories. And then the young woman I worked most closely with was in a really bad way. But she was the manager of the Sbarros in Eureka, and she is, they call it being "daddy. " And her trafficker said, "You know, he took her out to dinner. He lived in Sacramento. He found her. " She poured out her heart to him. He came up and visited her. He bought her presents he took her out to nice meals. And then finally he says, "I'm going to take you away for a weekend. We need to get you out of here. " And he drives her down to Sacramento, and they have a touring, romantic night. She's head over heels thinking, "This guy is going to take care of her. " The next morning her clothes are gone, her identification is gone, her wallet is gone, and there are these prostitute clothes that he's left for her. Turns out she's 6 feet tall. She is not your typical target. She's white, she's 6 feet tall, she's gorgeous, she's a big woman. And he's left these tiny clothes for her. And he gives her the option of either walking the track, which means, you know, soliciting men from cars, or going into a brothel. And she goes into a brothel in a fancy gated community in Walnut Creek and is forced to work in the brothel. And she escapes from a motel. Her escape is in the book. She's one of my heroes. And she starts an NGO for traffic girls up in Eureka called. . . I can't remember the name of her organization, but it's to what she's doing is training police officers to identify girls who are being trafficked, to pay attention to it, and to notice the signs of a trafficked girl. And this girl who you can Google her because she used this afternoon, she went by the name Elle Snow. And I talked about my relationship with her at the end of the book. She was terrified. I finally asked her if I could tape her story. And they kept meeting like at Starbucks and at the coffee houses in Eureka called Ramones. And I finally asked her if I could tape her. And she loved where our cabin is at Big Blue Boone. She said, "Yeah, let's go up there. " And then it turned out she was too frightened. You know, we were going to walk on the beach and call that baggage, and I was going to hear her story. And she never wanted to felt safe leaving the cabin. And we just ate and talked for days upon days. And she let me tape her. And I end the book with her story of her flight to freedom, which is pretty amazing how she gets free. This was an Egyptian girl. She is shipped from Egypt with a family that's being purged, a very wealthy Egyptian family. The dad is corrupt. And she has been sold to the family to replace her sister, who was apparently not a good nanny. So they do a trade, and she gets taken down to Orange County. And a neighbor notices in a park, "Why is this girl a nanny to other children?" And she calls social services. And this girl, Shema in the Hall, is freed by the neighbor. So I think, you know, now I notice things that I didn't look for or notice before. The neighbor frees her. She goes into foster care. The family goes to jail. She wins a big settlement, and the foster family keeps her money and takes her money. And she writes a book. It's a young adult book. It's really readable for those of you who teach. It's an amazing young adult bio called Hidden Girl. And this is a picture of this little shack above a garage that was posed after she was freed with her stuffies. But it's an amazing story of what happened to her, how human trafficking happens, and how a neighbor frees her. And she takes the family to court. They go to jail, but ultimately she loses the money. This was a Thai restaurant worker. He's a welder in Thailand. He's recruited by a high-end company from Napa Valley. And he's a welder, and they say, "You're going to get to come repair the Bay Bridge. " Remember when the Bay Bridge gets broken? Well, welder would not want to come to California and work on the Bay Bridge. He lands at SFO, and he's put in a white van, driven down to LA, and he's forced to rebuild a Thai restaurant in LA. And, of course, is not working on the Bay Bridge, and he's sleeping on a cold floor, no furniture. Rebuilding the restaurant, opens the restaurant, and a familiar customer realizes something doesn't make sense about this kid. And he takes the kid to the Buddhist Temple in downtown LA, where a collection of trafficked Thai workers have gathered, and they win their freedom. And he wins the right to weld on the Bay Bridge and break his family with a green color. I'm going to end with Yogleen. Yogleen is my hero. She was an enslaved prostitute, taken up to Sonora, and she writes this affidavit. And she climbs the steps of the Sonora courthouse, and she writes this affidavit where she says, "My husband Charlie is in jail. " Charlie was a kind of derogatory name for Chinese men, one homogenized name. She said, "My husband Charlie is in jail, and I've written this affidavit to declare that I am a free woman, and no man may ever own me again. " Thank you. [applause] I'm happy to take questions. I talked for over an hour or so. You almost have the wiggle system. But I'm happy to take questions. Yeah, thank you. When did the Indian schools in Riverside County, or Riverside County, well Sherman's also, when did it change? You know, it evolved. I don't think it changed, as I understand it. Right now it's a very popular, and actually it's very beautiful. And talking about Taco Bell architecture, the owner of it, he was in Paris, P-E-R-R-I-S, and he wanted to build a bigger Indian school in Riverside, and he comes in and deals with the city of Riverside saying, "I will build a tourist attraction, and it will look like a mission. " And Sherman Indian School, you can Google it, looks like a mission. Why did you go with that? It's around the turn into the 20th century. It's like about 1908, 1910. It starts in about the 1980s. California always needed a labor force, which is just such an invitation to unfree labor. The reason I'm asking this, I think I visited there as a little girl. Really? Written in the late '40s. My mother and her friend were archaeologists who were in South America, in the Southwest. Can you all hear the amazing story there? They were very, totally for the Indians. I remember I met with my mother and her friend there, and I got two little books, whatever, about Indian children. Yeah. Well, I haven't, actually the truth is, I haven't looked into the 1940s. I looked into the origins of Indian schools, because I was so surprised to hear about the accounting programs, which was what these schools were for, and that's how Hall cuts this deal with Riverside, is that I will supply the orange groves with child labor if you let me build this school here. And he took kids from all over California and Native American friends we have, your aunt friends, and HUPA friends up in Humboldt, talk about, you know, their parents would know, and the stories of the descendants of kids, probably many Native American people in California have families, ancestors who were in the boarding schools. I got a chance to interview this, one of the Supreme, the investigation in Canada was run through the Canadian Supreme Court with a brilliant judge named Hugh Murray, and I got a chance to meet with Murray, and he brought with him, it was to a seminar, but I got to spend time with him, and that's when I realized I needed to look into this in California too. And he brought with him videos of the testimony before the Canadian Commission, and it was mainly old men, and they were sobbing, and they would always stand up, one with another, and they would talk about and confess that they were abusive fathers and abusive husbands and alcoholics, because that's the childhood and the survival that they had gone through in the Canadian boarding schools. And that whole report, Hugh Murray's report, the Canadian report, is in my view what cracked open American scholars looking at the Indian boarding schools, and then when I discovered there were 12 in California, four that really endured, and all built on the Carlisle, Pennsylvania method. And they'd meet every year, they'd have these big meetings on how do we do it, and Carlisle was the one at the center on the Designing the "Outing Programs" that were copied very closely by the California boarding schools. But I don't know the history of how they evolved. I was just, when I went into the archives, I was really surprised at how well respected and competitive it is now to get into Sherman, because those kids go with athletic scholarships and some decent education. There are amazing biographies of, by the kids, some published that I can, you know, and they're in the book of their stories of how they came to California. It's almost like the prison system, you know, where prisoners are being shipped around all the time. These children were shipped around all the time. Like boys from Sherman harvested beets in the beet fields in Nebraska. So wherever they needed labor, these kids were shipped around often by train and alone, you know, and just terrified. They didn't know where they were, you know, to run away or escape, not like the little girl who thought she saw the arrow out the infirmary window. But I'd love to see those in those books. I've seen a couple of evidence that there's apparently with a boarding school in Nevada, just close to Carson, in this Carson City, and their children, little girls, were coming in the Nevada City, Nevada County, to serve in the households of some of our famous citizens. And I wondered if they were purchased or they were paying the school for-- They paid the school. And one of the parents' claims was for the salaries that these kids allegedly got, that of course never went back to the families. But it all filtered through, yeah, it went through the schools. And there's one case where they had a little girl who was so unhappy she was crying all the time. But rather than send her home, they said, "Oh, just bring her sister along and she'll cheer her up. " Yeah. So it's just, you know. There are stories of some of the older girls who were sent to Los Angeles. They're in the book. And they just--because they were older teenagers, they found their way around L. A. They found each other. They partied. They would go out at night and finally they ran away. But it was the little ones that were really the most fragile and the depression that you'd see in those faces. And it was very much the parents who were trying to make legal challenges, but they were stuck by what looked like a good law that every reservation kid needed to get an education, was entitled to an education. Sounds great. Except that was the education that they got. So they were working--the boys were working in the orange groves. A lot of them were taken in and protected by Mexican field worker immigrants who would live in these barracks with them, who would protect them and kind of raise them. But they didn't speak the same language. But they taught them farm skills so the kids wouldn't get beat up and the boys would survive. And the girls were in much more-- we may learn more about the sexual danger the boys were in, but the girls were in very obvious sexual danger in the households. It's very much like the Irish servant girls in New York who were working in households without anybody there to protect them. Other thoughts or questions? Displeased. Thank you all very much for your refreshments for coming out tonight. [applause] [APPLAUSE]