Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2023-07-23 - The Ditches of Nevada City with Dom Lindars (66 minutes)

For its first 100 years, everything in Nevada City revolved around gold. But this is not another book about finding gold. To get gold, you needed water — to pan for it, to blast away a hillside with a water cannon, or to turn the water wheel for your quartz-ore stamp mill. This book instead asks: Where did the water come from? It reveals the engineering marvels that brought water to Nevada City's dry hills from tens of miles away. But what if all the water in every ravine, creek and valley around Nevada City was controlled by just three men? Well, for three decades, every miner, farmer or business had to buy water from the South Yuba Canal Company. What would happen if you got into an argument with them? Or couldn't afford to pay their water bill? Or even dared to compete with them?

The book traces the ingenuity and hard work of the town's miners and ditch builders, highlighting the origins of various local neighborhoods, including Nevada City, Willow Valley, Gold Flat, Selby Flat (near Sugar Loaf Mountain), Rough and Ready, Randolph Flat (now Bitney Corner), Alpha, Omega, Blue Tent, Cement Hill, Hirschman's Pond, Manzanita Diggings, and Scotts Flat.

What began as a search to uncover a sprawling network of old ditches, turned into a collection of never-before-told stories of the gold miners, the ruthless and greedy ditch company, and the rivals that it crushed. The domineering ditch company later enabled the next generation of monopoly to provide electrical power. This, in turn, led to the now more forward-looking stewardship of the Nevada Irrigation District.

The unique format of this book blends beautiful archival images with more than 35 in-depth biographies of key figures in Nevada City. This 884 page hardcover book includes over 600 full-color illustrations, including 200 historic photographs and 75 hand-crafted maps based on modern lidar technology that reveal the locations of the old mining ditches, flumes, mines and tunnels. For more information, please visit the website, nevadacityhistory.com.

The book traces the ingenuity and hard work of the town's miners and ditch builders, highlighting the origins of various local neighborhoods, including Nevada City, Willow Valley, Gold Flat, Selby Flat (near Sugar Loaf Mountain), Rough and Ready, Randolph Flat (now Bitney Corner), Alpha, Omega, Blue Tent, Cement Hill, Hirschman's Pond, Manzanita Diggings, and Scotts Flat.

What began as a search to uncover a sprawling network of old ditches, turned into a collection of never-before-told stories of the gold miners, the ruthless and greedy ditch company, and the rivals that it crushed. The domineering ditch company later enabled the next generation of monopoly to provide electrical power. This, in turn, led to the now more forward-looking stewardship of the Nevada Irrigation District.

The unique format of this book blends beautiful archival images with more than 35 in-depth biographies of key figures in Nevada City. This 884 page hardcover book includes over 600 full-color illustrations, including 200 historic photographs and 75 hand-crafted maps based on modern lidar technology that reveal the locations of the old mining ditches, flumes, mines and tunnels. For more information, please visit the website, nevadacityhistory.com.

Author: Dom Lindars

Published: 2023-07-23

Original Held At:

Published: 2023-07-23

Original Held At:

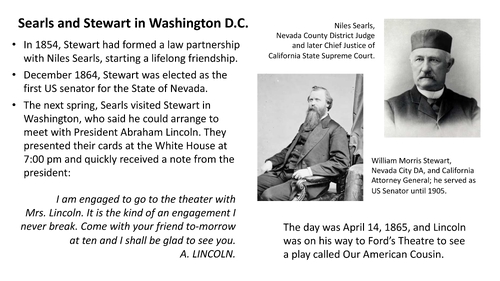

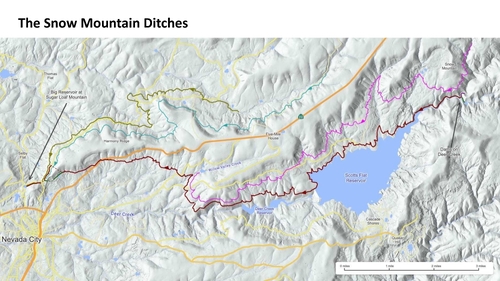

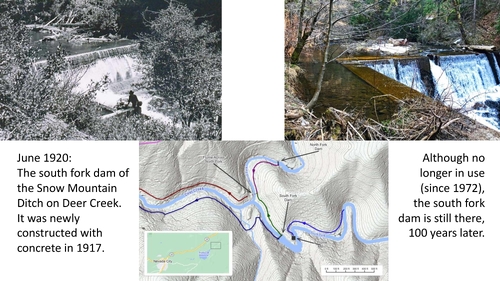

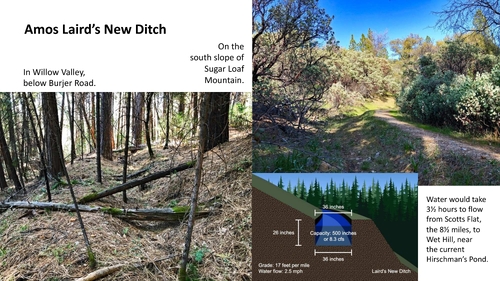

Full Transcript of the Video:

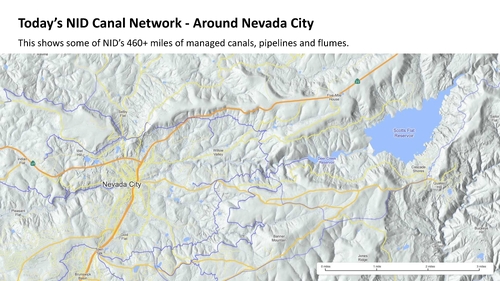

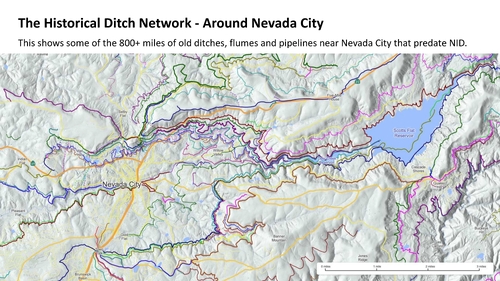

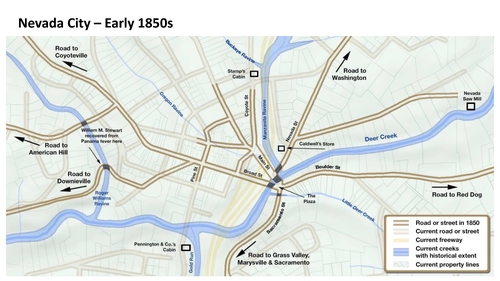

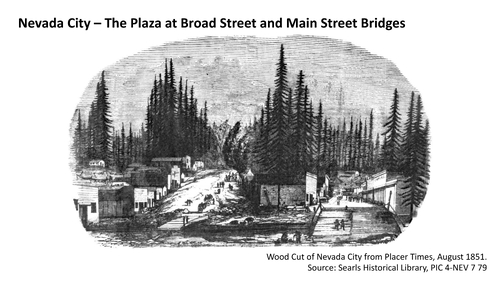

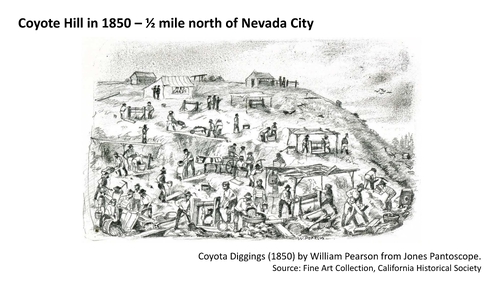

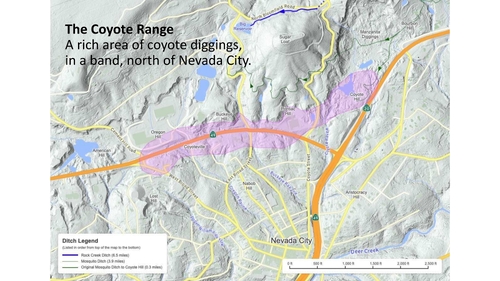

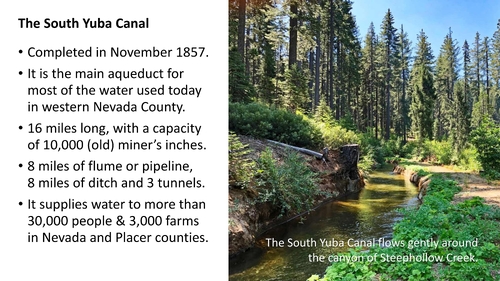

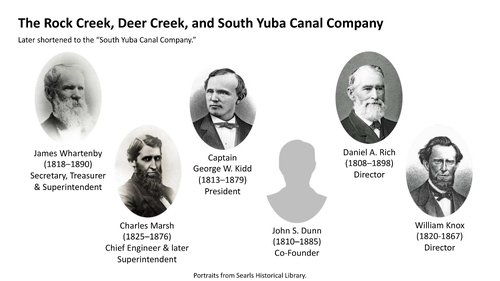

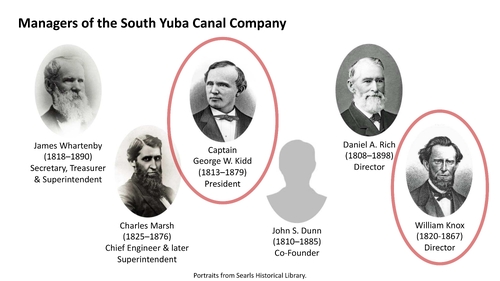

Tonight we have a local author and as I mentioned new society board member will be sharing with us a bit of this how many pages? 884. 884. I said total on just who how and they who created our public water supply that we enjoy here in Nevada City and the rest of Western Nevada County we're going to learn about that because every time we turn the faucet really started with whether he's coming tonight so that's it. Good evening thank you so much for coming and thank you for supporting that. I'm overwhelmed by how many people came tonight so thank you so much. So as Dan started so this is actually a 15 hour lecture. Forgive me for rushing but I want to try to share some stories as you can tell from the book there's lots of stories about fauceting history and I just want to share a few of those some of my favorite parts of that and and I know what's talked about where it came from and a little about how I did the research as well. So the book really asks the question where did the water come from and so we can think about today about you know both from a gold mining perspective it's not just about hydraulic mining but up until electricity was widely available in 1910 all of the local hard rock mines were entirely powered by golden wheels and water. So where did that water come from? There's actually two sets of that. And then even then beyond that what about all the water we drink today? What about the farms and irrigation? And so all of this leads up to you know what we see today with NID. So how many of you go out on walks on NID notification canals? You know what I'm talking about. It's my favorite place to walk it off because it's nice and flat. So for those of you familiar you know some of the locations so for example we've got Snow Mountain ditch and cement hill ditch, Red Hill canal, DS canal, cascade ditch. So these are just the current NID managed foods but if you step back in time a moment that represents there's an additional hundred ditches overlaid on here that go back to the gold rush and actually that represents so I've mapped out both with GPS and just out on maps themselves about 800 miles of local ditch here but actually that only represents a small fraction of what's going on in Western Nevada County because I haven't mapped them all. And I'd say because that probably represents maybe a third or a quarter of the ditches that are out there. So I don't even know how many we've got just in Nevada County. Never mind the rest, post the rest of the foothills. So first of all, how is I doing some of this man-building? So I'm going to talk a little bit, mention a few times, LIDAR, which is essentially it's an airplane, an aircraft flying over bouncing a laser off the terrain and the trees and it can map everything incredibly accurately and we were fortunate enough to the USGS to have a survey of Northern California to provide a baseline for soil erosion for wildfires. So everything burns down, you know, you get a flood and things wash out and you want to see what's happening to them. So using this you can see on top of here you see some white lines. Now a couple of these are old roads but actually so this is on Deer Creek and that's actually Pascuali Road there. So those are the ditches and so the little white lines, that's how you can actually see the ditches. So this is sort of how somehow I've done some of the research. Other parts of the research painstakingly going through transcribing law, law and law and the legal cases in the soils library. How I'll show you a wall full of legal cases. Well I spent quite a few weeks transcribing a couple of key lawsuits that actually led to the core content, some of the books here. So there's a lot of detail. So let's sort of flip around a little bit and feel free if you want to ask questions. Hopefully we run out of time too much but happy to ask questions as we go through. Oh we have a question already you see. Oh there you go. All right. Okay good. I give in. See I can't see you now. Can you see that better now? Yes. Good. Okay so let's talk about Nevada City. So first of all how many of you have had somebody say, "Oh you live in Nevada City in Nevada?" Right? Yes that's right. Yes we're in California actually. Yeah and that rogue state. So did it steal our name? Well so let's drill into that. So well first of all just need to say for centuries the area that is now known as Nevada City was called Utsuma by the Wumisan people. It's been Utsuma and all along and there was Nevada City. So you just need to remember that. When the miners came along they weren't very clued in with good names. So it was a dry creek, sorry deer creek dry diggings or a cold well is up a stalk because cold well is out of the storm. So in 1850 the miners voted to get a better name and they chose Nevada. Basically snowy. But all the way from the beginning Nevada City was always called Nevada City. The post office, the way it was incorporated, it was always called Nevada City. But it was the only place called Nevada and so there was no confusion. So we were just told it's like New York. Do you need to call it New York City? It's the same thing. And I'll just point out that Nevada City was really big in California. So even by 1859 it was twice as big as LA. That's where actually combined with Grass Valley I should say, the Nevada City Grass Valley community. Twice as big as LA, twice as big as Stockton, twice as big as San Jose. So we were something. Let's not forget that. So there was no confusion until the Nevada Territory came along and to be fair in their records they actually specifically say oh it's just a straw name for Sierra Nevada. It didn't actually say in the Nevada State Constitution we deliberately stole the name from. It just happened. But then to avoid concrete confusion yeah everybody started using Nevada City as their name. So that's how we got to, that's how we firmed up with Nevada City rather than that. And I'll actually also point out that being an English guy I am pronouncing Nevada wrong. I would like to acknowledge that. So would you like to use, Jeffrey you want to be safe? Nevada. Okay I'm sorry. And you'll call me out on all any English's and so I go along and that's fine. If I don't mind. Okay so let's take a look at downtown Nevada City. So we've got a few interesting things. So the first cabin built here was by Pennington. So that's just the south end of the South Pine Street Bridge. And then the first family was Charlie Stamp and his wife Matilda and I think they had a couple of kids. That was up Paggy Street, Washington Bridge. And then Caldwell's store is right here. That's the later the site of Charles Marsh's house. So that's on Nevada Street, that high street in the way that is. And then you know some of the exact roads were a little bit but then down at the bottom here, at the bottom of Broad Street, you've got two bridges. So you can see where the freeway goes through now. And we don't have the Main Street Bridge anymore here. Sorry we don't have Main Street going across but we have Broad Street. So you've got the two bridges there at Broad Street and down the street. And this is what they look like in 1851. So you've got Broad Street going up here and the bridge over here. And that's Main Street going up. And so that's what they look like. So where is that now? Or so if you go to the Stonehouse Brewery parking lot, all the lefties, T. J. 's Roadhouse, and then look up the hill and that's Broad Street. And that used to be Main Street going all the way up but obviously that's now the Broad Street because it turns the corner and goes up the hill. But I just thought that was kind of cool just seeing what it used to look like. So another different view, Coyote Hill. So this was an illustration of the coyote diggings which were the coyote shaft was a round shaft that they used to dig down to get to the bedrock. And it was two or three feet across and they used to throw the dirt out on each side. And so that's why they thought that looked like a coyote digging, a coyote hole. And that's how that got its name. But you can see that all the miners have the wind lasses like lowering buckets down to the left of the dirt. So there's a lot going on. A 30 foot square claim and they might be digging down there. You can dig down, you can send four weeks digging down 100 feet and find another. And the guy next to you would dig down 100 feet and sell his claim for $10,000. It's literally like neighboring claims. You never knew what you were going to get. So also on Coyote Hill, and this is a fairly famous photo. I'm sure quite a few of you have seen this photo before from the California State Library. So this was actually one of the digg company offices on Coyote Hill. So after you've bought some water for your mining, you need to go pay your water bill here. And that was one of the offices on Coyote Hill. And so this is what Coyote Hill looks like today. So this is the south end of Manzanina-Diggins. So just above Highway 49 and then just west of Highway 20. It's just near the intersection there. And just imagine that the hill was going up probably about close to the height of those trees is where that previous sketch was. And it took them about 15, 20 years and they washed the whole hill away and it's just over the bedrock. Pretty crazy, right? So we take a look here and you can see that the pink area here is what they used to call the Coyote Range. And it was a set of hills that they had all of these different coyote digging. So you can imagine each one of these hills look like that sketch. And so you've got Coyote Hill, Pontiac Hill, Williams Hill, Buckeye Ravine, Buckeye Hill, and there's the library today. Coyote Hill, which was, Coyote Hill is separate from Coyote Hill, but it was a small town. It was nearly as big as the Bobb City Warhol. And then you've got Oregon Hill and then American Hill and Wet Hill and it sort of carries on. So the whole of this was all those Coyote mine shafts. And so let's take a look. So the Madeline Telling Library right here, so Buckeye Hill. What did that look like in 1852? So actually you can see, so this is near where the library is and you can actually see that's cement hill in the background, kind of looking west. So the whole cabin, a couple of miners, they've got a sluice box, they're shoveling their paint out in here. So we actually know that this is William Morris Stewart and his palmer, Dr. Merrick. We don't know much about him, he was a bit of a shady character. But Stewart was a pretty interesting guy. So he ended up being the first senator for the state of Nevada. You can blame him for a state of the name, maybe. So he was born in New York and he grew up in Ohio. So Buckeye Hill, he was one of the Buckeye boys. So basically he serves a large number of Ohioan's from the Buckeye State, the mines there, and they had three or four cabins. And so he was an active miner but he realized that mining was actually quite hard work. So he switched over to becoming a lawyer, which is, I don't know, no offense to any lawyers here. So he pays well and in fact Stewart made various different fortunes from representing mining, competing mining claims. So one of the things as a DA of Nevada City, he actually prosecuted a very famous case. George Hall was found guilty and sentenced to hang for the murder of a Chinese man named Xing. A crowd of eyewitnesses all said he did it, pretty much in cold blood, open a truck case. It was then on appeal of the California state court that the court reversed the decision and Hall was set free. And they found that the eyewitnesses, their testimony was invalid, essentially because they weren't white. And so this set a legal precedent for decades in California that led to the discrimination of abuse of the Chinese. And particularly nobody in the Chinese community can complain, like for example, suing somebody because anything they might testify wasn't an admissible court. Leaning up to and including the Chinese Exclusion Act and so forth. All of these things in California led to decades of wrongdoing, they lasted until World War II. But that trial that Stewart successfully prosecuted led to a lot of things in the future. So when Stewart went to Washington, just before Stewart went to Washington, he actually became good friends with Niles Sills. So many of you here, I'm sure, apart from Sills historical library, I have a clue, was out of Sills Avenue. So, you know, Judge Niles Sills was a district court judge here and later on Chief Justice of California Supreme Court. He visited Stewart in DC and Stewart says, "Oh, would you like to meet the President? I can arrange a meeting. " So they went along to the White House and presented their cards and they got this message back. "I'm engaged to go to the theater with Mrs. Lincoln. It's the kind of engagement I never break. How many of your friends are tomorrow? That's ten. I'm glad to see you. " Abraham Lincoln. Now before you get going, where are you going? As they were walking away from the White House, Lincoln was getting in the carriage to go to the theater. And he saw his friends too. And he ran over. He said, "Oh, I'm so sorry. I'm late for the theater. I've got to go. But oh, who's your friend? Oh, nice to meet you, Mrs. Sills. Thank you so much. I'd love to see you tomorrow morning. " So Judge Sills was just tickled pink. He just was like, "Oh my goodness. You know, thank you. Thank you, Bill. I've met the President. I shook his hand. I heard him speak. I don't need to bother him tomorrow morning. I don't want to waste the President's time. That's right. I'll go. " And so Stuart actually saw him off the railroad to go back to New York. But yes, that evening was April 14th, 1865. And indeed Lincoln was on his way to go to the court still. So it turns out that note that he wrote to Stuart was the fourth to last thing within the neighborhood. Stuart threw the piece of paper away because he didn't think it was important. Lots more about his story in the book because that was actually the beginning of the Knights of Ventra, obviously, that took part in Washington, DC before we had a new President member. So Stuart went on to have a very successful, long Senate career. One of his most outstanding and memorable things at this point was the fact that he actually wrote the 15th Amendment, which guarantees voting rights regardless of race, color, or previous enslaved status. And so obviously this was a ground setting, a big precedent for at least guaranteeing universal vote. Well, at least for 50% of the population. It would take another quite a few decades until 1921 for the 19th Amendment to come in to actually to give the other half of the population of the women the right to vote. And of course, please remember the 19th Amendment was written by another Nevada city lawyer, Aaron Sargent. Okay, so a quick little talk, you can get an idea. There's 35 biographies in the book and they all have some stories that in the early Let's talk about why water was so important for mining. So right from the beginning, the gold rush, people were finding gold in rivers. But as soon as the gold in the rivers ran out, they had to start searching around in the hills, in the ravines, and they didn't necessarily have water. And so quickly, they got in the situation where they'd have to hold the pay dirt down to the water, for the water back up to the pay up to their claims. And minus hated that it was a big waste of time. Now they had this new technology like the rocker. So this was actually something that was invented in the Georgia gold rush a few days earlier. So it could process gold about two or three times faster than a gold pan. But you needed a little bit more water. The next invention actually, which was in the city thing was the long time. So it was a forerunner of a sluice, because basically it was a long board with some holes in it. Now you need a constant supply of water to keep that one. And but it was very productive, it was about 10 times more productive than a gold pan. But it also lose some of the gold, you actually could lose 25 to 30% of the gold, just running out of the end. So not very efficient. So faster, but not very efficient. And then that led to the sluice box. And sluice boxes used to often be three or 500 feet long, all strung together with ripples or baffles in the bottom of a flume. And that would collect the gold as the water went by. So they worked out as a lot less work. All you had to do was shovel the dirt into a sluice box and the water did all the work. So then the next step of that evolution was, well, hang on, if the water is doing so much work, why do we have to dig? Why don't we point the water at the dirt? And so obviously that led to hydraulic mining. So history reports that Eddie Masson first demonstrated hydraulic mining on American Hill on March 7th, 1853. Now, so if you think about where that was, so American Hill, it's a little bit nebulous. It's like, oh, I've got a house on American Hill. It's like, okay, actually, it doesn't really tell me where in the city. It's somewhere there. So specifically in 1853, American Hill was, think about it as halfway between the county buildings and Hirshman Pond, north of Highway 20, somewhere around Smithill Road. So that was where American Hill was. And he got together with a miner called Anthony Chabot and a tin smith called Eli Miller. And they put together a sewn riveted hose and they put a nozzle on the end of it and they used 16 inches of water. I should say, if I'm talking about the quantity of water, people know what a miner's inch is. Okay. So that's basically like, think about a square area of that many square inches of water flowing through a hole. We'll come back to that because miners inches kind of a problem. So he was using 16 inches of water. Now, but the thing is, a year later, sorry, a year earlier, Chabot had actually been doing this for a year. He actually had a hose and he had a pressurized water box from a flume. And he was actually, you know, washing down gravel for a year before Madison actually even got his, but he didn't have a nozzle on the end of his hose. So Madison's invention was the fact that he put a nozzle on the end of a hose that had already been used successfully for a year. But the thing is, Chabot, he was really good at anything he did. So he later went on to found various different water companies, city water companies in the Bay Area. He would so much so that he was known as the water king. And, you know, anything down in the Bay Area that has the name Chabot on it, that's for this guy. Died a millionaire, had a good happy life. So he's got all sorts of going things going on without having to claim that he invented hydraulic mining. Madison, however, it's like he never made a cent from hydraulic mining. And he was actually, he was a pretty good inventor. He vented a bunch of other things, but he never had any business sense and never was able to make any money out of these things. So he was broke. And, you know, people even in the city who tried to look out for him to try and generate some charitable donations from California state legislature to recognize him. But he died broke, was buried in Pine Grove Cemetery. So, so, so bored, you didn't have a gravestone. You don't even know where. So I think it's very right that he is recognized for his inventor of hydraulic mining because he didn't get much else for it. So you can see here, it's an example of early hydraulic mining. We're used to seeing the huge big monitors, you know, North Bloomfield powering the water through cliffs. Well, this is what it looked like for the first 10 or 15 years. It was just hoses, you know, coming down from a flume. And, you know, so 10, 11 guys could actually run this and wash down to the bedrock. So it's pretty interesting. But then, you know, by 1870, it started getting big. So the exponential growth of water. So do you know the hydraulic monitor that's in Callanon Park downtown? I think it's a 12 inch nozzle. So just think about it in 12 inches wide. So, but that wasn't even the biggest. There was one that went to Blue Thames that was 18 inches across. And they couldn't even have had, they had a water supply of about maybe a thousand inches a day at best. And so they could only run it for maybe an hour at a time, because they'd have filled up this huge reservoir. It was a, I don't know, it was like 15-acre reservoir. And they could run that thing dry in an hour through this monster. Just incredible. So quite a few of the monitors, the original monitor, the globe monitor was actually was invented by Randolph Craig, who was a miner that worked and lived just west of Hershman Pond. And so that was all a local local invention. And many of those things were either cast in the Bada city or actually Mary's ville. So all created locally. So do you get an idea about you might need some water? And that's before we even get to hardware mining later on. So let's just talk quickly about some of the early ditches. So the first was a mosquito ditch, tiny little ditch. Can you see, can you kind of see that there's an indent of a ditch going through here? So it was just, it was 18 inches wide, about a foot deep, 75 inches in capacity. So you could keep 10 long time visitors for a day. But boy, did they start making some money out of that. So you can see it went to Deer Creek, down here, Mosquito Creek, Fly Creek, and then Coyote Hill. And so if you want to see Mosquito Creek today, actually, if you crawl up the bank on the second turn of Coyote Street, you can see it up there on the left hand side. And then if you go up North Bloomfield in the first corner, you can look up and there's like a U-shape. That's Mosquito Creek, Mosquito ditch from 1851st ditch. And then again, on the Rock Creek ditch, they, it costs $10,000 to build. They thought they were crazy. That's never gonna make money. Yeah, it paid for itself in six weeks. Crazy. So it was built by John Dunn, William Crawford, two merchants in Nevada City. And they got some advice from a civil engineer called Charles Marsh. We mentioned it earlier. Now John Dunn was actually the person who coined the phrase "minor's inch" because he was the first person selling the water out of the Rock Creek ditch. And you can see this is the Rock Creek ditch as it looks today off North Bloomfield Road. And you can see it starts up here on Rock Creek, follows Cooper Road, and then follows North Bloomfield. And then Sugarloaf and ends up with this reservoir, big reservoir, just next to Sugarloaf. And that's what it looks like. Well, I was gonna say that's what it looks like today. But that's what it looked like last year. Actually, I think the photo's maybe three or four years old. But so big, big reservoir or Sugarloaf reservoir was a continuous operation from 1850. Unfortunately, due to leaks, it's been leaking for more than 100 years. NID actually decided to close it down last year. So it's actually looks more like a flat field now, which looks sad. But that's what it looked like. And it's been in use for 170 years. Okay, so lots of other ditches. I can skip over, but we don't have enough time. So I'm gonna keep going. And there's lots of other things we've talked about. But I want to talk about the snow mountain ditches. Jeffrey mentioned that earlier. So it's one of my favorite walls. And they put well, snow mountain ditches is actually three ditches. There's a rock creek ditch. There was a an upper or a little ditch, mainly because they ran out of money. And then there's the real bit itself. And so if we take a look here, there's the rock creek ditch. So that's the original one. And then there's this new one. And then they dug the first half of the snow mountain ditch. And they got as far as Bully Valley. And then they ran out of money. Mainly because this section here, two miles of flute, very expensive to build. It's nice and cheap to get a crew to be able to take a ditch, but not to build a flute. And so they ran up here and they actually ran around and went all the way up here up close underneath Cassie Road to Cold Mountain Cold Spring Canyon. And that they could dig that old ditch without having to do any expensive flutes. And then from the money from they got from selling that, they actually were able to then pay for the extra cost of building this out. If you go to Scotts Flat on the north side of Scotts Flat, anywhere along there, you see an old dry ditch. That's the old snow mountain ditch that was in use until 1972. So this was the little snow mountain ditch that ended up just like as a top up ditch that ran into Bully Valley Creek. And then here's what snow mountain ditch looks like just east of Scotts Flat. It's a part of a flume that sort of runs along that. That flume was probably from about 1950s, 1960s. And that was the main water supply in Nevada City right up until 1972. You can see here that there were two dams that turned the water around Deer Creek. And here's a picture from 100 years ago. There was a brand new three-year-old concrete dam that they just put in. PG&E constructed that. You know, 100 years later, it's still there. Looks pretty much the same. It's been abandoned for the last 50 years, but it's pretty cool if you want to go out there and take a look. And so snow mountain ditch today, it's like, yeah, this is one of my favorite walks today. It's just a wonderful peaceful, shady place. It still supplies water to two other canals further on and provides water for homes and farms. Okay, so my favorite story here is about Amos Laird and his new ditch. So take yourself back to 1855. So Amos Laird at the time, he was one of the richest gold miners in the Bunk City. Of the previous 18 months, he pulled out half a million dollars worth of gold. Now that's before expenses. But he was probably still 70 or 80 percent margin. So he still made a lot of money out of that. So definitely one of the richest individuals in the Bunk City. But he was fed up paying ridiculous amounts of money. He was paying something like $10,000 a month to the ditch company, to the water company to pay for, to get water out of the ditch to provide power, his power to hydraulic mines and hydraulic canons in his, in his claims. So he said, okay, I'm going to build my own ditch. So he wanted to build an eight mile ditch. So you can already see that it's getting quite busy there. So he managed to squeeze a ditch right in between eight mile ditch and with a dam of Scott's flat. And because the deer creek was, they had so many other ditches pulling water. He had, he had a new water right. He had no right to wear any of the water in there. It was already claimed many times over. But when there was a big storm, he could collect the runoff. And so he decided to build this reservoir, 100 acre reservoir. And so during the winter he could fill that up and then he could, he'd never be able to get much water, claim water from the ditch from the creek during the rest of the year. But when he had a full reservoir. So a big reservoir up there in Scott's flat, very much a precursor to the reservoir we have today. So you can see evidence of Ledge new ditch. This is what it looks like on Sugarloat Mountain and off Berger Road on the public land there. It's a pretty good size ditch. It was, it was used for quite a long time. And so one of the big problems was that people were suspicious of that very large dam up in Scott's flat. And they were really concerned about that amount of water. What would happen if that dam broke? So much so the Nevada Journal said, if the dam should break, the slumbers in the lower part of the city would undoubtedly have rather a moist time. They added, I didn't have quite room for the quote here, but they added, but we will sleep very comfortably because we live in the upper part of the city. Well, two weeks later, it started raining. What we call an atmospheric river storm. We know what that was like. We had like nine of them in January. Nevermind the snow. So it had been raining for three or four days. And that dam and that reservoir up at Scott's flat was getting fuller and fuller and fuller. And then at the middle of the night on February 15, the wooden part broke catastrophically and 600 million gallons of water started heading down Deer Creek. So eyewitnesses recall seeing a tidal wave 15 feet high. So first of all, the river was already immensely high, right? You know what Deer Creek would look like if it's fizzled, if you were to look like when it's when it's quite full. So imagine 15 feet on top of the storm level. So it swept through and you know, all the buildings down close to the river, close to the creek, pretty much in danger. So you may recognize where this is. So that's Stenhouse Burrow in left. He's on the right now, TJ Roebhouts. So this, that's the Nevada street bridge used to be the main street bridge. So the water came down there and all of the debris backed up behind that bridge. And so the whole of that area started flooding several feet deep in just a few moments. And it started to lift the water, started lifting all the wooden buildings off that foundation. And the bridge started lifting up this foundation. And then so it lifted up and the water searched forward and it slammed into the bridge, the Broad Street bridge on the right. And then it backed up some more and the Broad Street bridge lifted up and whole houses and two bridges, oh and half a hotel. So it's very interesting. The monumental hotel, it was on main street, it broke into half of it, lifted up by the water and the other half completely intact. They'd exactly what it was. But seven houses, the monumental hotel, two bridges lifted up by the water and started floating down towards the rapids, hit all the boulders and everything was all smashed up. Little bit of damage. So allegedly there was no loss of life. But I can't really believe that's necessarily true. There were many mining camps that were completely washed out. To give you an idea, there were two stamp mills down on Deer Creek, sort of kind of like down below where the South Pine Bridge is today. So they found some of the stamp mill pieces half a mile down the street. A lot of damage. So anyway, so Laird and his contractors got sued, about $10,000 in damages against him, but he appealed. And once again, the California Supreme Court came in and said, "Oh no, we don't like whatever you're doing in the city. We're going to reverse that decision. " And so the California Supreme Court found that Laird was not liable for his dam because he hadn't accepted, but the dam wasn't finished and he hadn't accepted the work. Now interestingly today, it is California law and is known as the accepted work doctrine that contractors are liable for third-party injuries up until the time when the work is accepted. And that is a case law that was established in Boswell, as in Boswell and Hanson's provision store. That was one of the stores that don't lift it up and float it down the river against Laird in 1857. And it's repeatedly been cited in modern cases, most recently in 2008. We'll say the Moore and Foss, they actually have the same lawyer as Laird who promptly threw him under the bus and they lost everything. Okay, so last big topic here and then we'll get on to a couple of other stories. The South Yuba Canal. So the South Yuba Canal is still the main artery that delivers nearly all of the water to western Nevada county today. It provides what are for about 30,000 homes and 3,000 farms in both Nevada and across the county. And so it's about 16 miles long, half of it's flooned or today pipelined, about half ditched. So it was finished in 1857. So if you take a look, I'm not sure if you've been up to Lake Spalding. So this is 80 and that's 20 and Lake Bowman Road here, Lake Bowman is somewhere up there. And that's Lake Spalding. So just below Lake Spalding's dam is where the South Yuba Canal starts. And then it comes down through Bear Valley Gap, traverses along the side of Bear Valley, goes through a little tunnel and then winds its way through Steepe Hollow Creek and then ends up at a 3,000 foot long tunnel that breaks out into Deer Creek. And so that was, it was called at the time the largest engineering project in California's history. Now, you know, in 1855, it's not much history but it was still impressive at the time. So where did it start? Well, it actually started as a company formed in 1851 by a city businessman specifically to go and build a South Yuba Canal. In fact, they had the company was called the South Yuba Mining and Sacramento Canal Company. Quite a mouthful. And they commissioned a survey by Captain John Day, civil engineer from Grass Valley. And he worked out that it would be about 22 miles a ditch and it would cost about a million dollars. So in adjusting for inflation, you can roughly times by about 35. So, you know, about $35 million project and quite substantially. Now this map, so obviously the company they formed, the idea was that they would raise money to do the construction by selling stock in the company. Those of you familiar with our history know that there are a lot of companies that were essentially money schemes. And so a lot of people thought that this was a money scheme to the point where this map was actually created by a map maker in London to sell stock in Great Britain to anybody who would buy it. But the map is fascinating. So the interestingly that top piece here actually looks quite like the map I just showed you. So like Spalding would be about here. But then they just like, oh, well, Deer Creek just kind of runs down there. So we'll just run the water down there. They avoided mentioning the additional 36 miles a ditch to get to Nevada City or the additional 45 miles of ditch to get to Grass Valley. Oops. Oh, never mind. But what's great is that there's actually places on here. So it's a little too small to see, but that one says Round Tent. Nowhere called Round Tent. There's a place called Round Mountain and there's a place called Blue Tent. Okay. They must have written it down wrong. Newtown is that one there, but Newtown is actually Western Nevada City. That's Nevada City. That's supposed to be Nevada City and Grass Valley. So you can see the topologies all work. Anyway, so half of these yellow dots, they're all fictitious. They basically just put anything on this map just to try to sell some stock. I'm sure it'll do what's going on. Anyway, they dug a 60 feet of ditch. Fails raise any money and nothing else happened. So good try, guys. So instead, the Rock Creek, Deer Creek, and South Yuba Canal Company, that's the folk that they merged and combined from the earlier original Nevada City. These are the guys that had the monopoly on water in Nevada City. And then we're going like, all right, we know what you're trying to do here, except we can do it. We actually have the money because, oh, we have the monopoly on water. So we're making tens of thousands of dollars every month on water. So we can afford to build this. And so they started on January 1855. And this is part of the South Yuba River Canyon. And you see this in 1884. So this is 30 years after they started. But it goes down across here. And there's pretty much a vertical cliff here. They had to blast out a mile and a half of ledge. To form, basically, the flume on. And the first 60 feet was even harder because there was nowhere to blow it out because otherwise we'd break up the dam. So they just started tunneling straight through from the dam. So that's a little shack for going through the tunnel. And today, if you took this photo today, although it would be really hard to get to, you can actually see in the background up here, it would be the link small and down. So that's to give you an idea of where it is. So a mile and a half of flume. So they had to pretty steep cliff. They had to lower guys down on a rope. And then while they were hanging on the rope, they would manually cut holes, drill holes, or in gunpowder, and then blast away to get to form the ledge a mile and a half to put the flume in here. And they started at both ends, and they put people down in the middle, and they just got the mile and a half thing that blew that up. And it's anywhere from 100 to a couple hundred feet above the level of the creek. It's an impressive thing. It's not as impressive as, I think you've probably heard of, these flumes that are actually on the vertical cliff wall. There's a couple of those in the serum bar. This comes pretty close. And here's what it looks like today. So that's the modern pipeline. That section is actually still owned by PG&E, but NID recently bought the rest of the southview of the canal. But you can see it sits on the original ledge that they cut out in 1855. And then further down, you can see, so along Bear Valley, there's six and a half miles of flume. And this is the original, this had a flume sitting on it for eight years. And then this is the modern flume that's replaced it. It looks in pretty pristine condition there. It's kind of fascinating. And then just talking about what the modern flume, it's just such a beautiful flume. It's just amazing. So if you go off Lake Bowman Road, it's the Sierra Discovery Trail. You can actually walk through the back of the trail, see what the southview canal looks like today. So this is what part of the ditch looks like. So it's 100 years ago. And I was able to find somewhere, I think it's actually the same spot 100 years later, which is just some lucky photography on my part, I think. And then there's the tunnel. So to get through to the Deer Creek watershed, they dug 3,000, nearly 3,100 feet of tunnel. It was eight foot wide and 10 foot high. You start with flume running all the way through. This is from an inspection report that NID did a couple of years ago. But some of the tunnels today is lined with concrete and timber to hold it up. But there's actually a good section of it that still looks exactly like it did when they finished digging it out in 1857. It's pretty cool. So the southview canal was finally finished in 1857 in November. And they were able to pour about 6 to 8,000 inches of water into Deer Creek. It's pretty much doubling the volume of water in Deer Creek at any given time. But because as soon as they put it into a public waterway, their competitors were more than happy to say, "Oh, well, thanks for digging that canal. We'll take that extra water. " It was part of their distribution systems, like thank you very much. So it took the Southview Canal Company another four years before they finally financially and personally crushed Amos Laird. And he lawsuit after lawsuit, there's about 20 different lawsuits against Laird to acquire his mines, to acquire his ditches before finally in 1861 he sold the last, sold his share of his new ditch. And the Southview Canal Company finally had monopoly control everything in the bi-city. Laird left for Montana, Brook. So don't mess with these guys. So you can see on the left there the Southview Canal Company office. That was, you know, it's now the Chamber of Commerce next to the estate office, what was Main Street. And that was the Southview Canal Company's headquarters until 1880. So while we're looking around town, okay, who knows what this building is? Thank you. So the Ken Knox building, a brick building built just after the Great Fire. It was built a month after the fire in August 1846. And it had a dramatic hole for theatrical performances and there was also more offices. And particularly important for me, it's now a chocolate shop. So Ken Knox, that's right, Captain George W. Kidd, president of the Southview Canal Company and his investment partner, Dr. William Knox, he was a director of the company, but he was a little bit of a sleeping partner at the Southview Canal Company. But you know, these were, these are the guys that every time I look at that building, yeah, it was it was Kidd's response. Kidd specifically decided to take out there. You may have heard of another story called Hamlet Davis one time, I think, famous story in the city's early days, also crushed by Kidd and some of the actions there. So not the nicest of fellows, but I've got biographies for each of these fellows and some really interesting stories. And Kidd later became the captain of a steamer, steamboats from San Francisco to Sacramento, up to and including when one of his seamers, Boiler, exploded and more than half the passengers died in the explosion. Kind of a grizzly story, but actually he actually developed some character and was a nice guy that day at least. So anyways, while we're talking about these guys, Charles Marsh, who popped up again. So what do we have to thank Charles Marsh for? Oh, sort of forever, Susan first. Who knows what this is? Exactly. So there is Central Pacific Railroad President Leland Stanford, former governor of California, future Senate, for future US Senator. So he's, he's holding a mallet that struck the last spike. So apparently when he went to strike the golden spike, he missed the first time. But not to be outdone, the president of the Union Pacific Railroad who took the next one also missed. So you're pretty sure that neither of those gentlemen had actually ever swung anything in their life. So, so right, just a little to the left of Stanford, there's our friend. So Charles Marsh was one of the co-founders of Central Pacific Railroad. Six months before, Leland and the other members of the Big Four invested in his company that would then become the Central Pacific Railroad. Marsh stayed on as a director. He was also one of the engineers for the Central Pacific Railroad. As the Nevada County's first surveyor, he actually surveyed personally out of the field about half of the digits that we've been talking about. But the thing we really need to remember before, and frankly thank him for, is his fire protection proposal in 1960. So there had been so many fires, six major fires that are taken out mostly in the city. Not to mention, you know, tens of smaller fires. And so finally, nobody had done anything about it. Marsh was like, all right, this is the infrastructure you need. This is where the pipes go, this is where the fire hydrants go, this is how much water pressure you need. I mean, it's ridiculous. By 1860, they had been using hydraulic mining for what, seven years at that point? What's that? Oh, even a hose with water being named something. Is that good for anything else like in town? No, of no importance at all. And so this was actually the first serious effort. And so the proposal was voted on and succeeded. The miners foundry in in the city couldn't produce the spec of high pressure pipes that Marsh wanted. And so it's actually ordered in from Philadelphia with some new fangled hydrants, fire hydrants from New York. But he also built a 1. 2 million gallon city reservoir. So there's the, think about the libraries there, and then we've got the reservoirs just out behind it. So that was all finished in 1861. Sadly, that wasn't the last city-wide fire. So in 1863, there was another fire and the firefighters, so it was during that time, both of the firehouses in Nevada City got set up and fully funded and full of equipment and everything gets going. They opened the fire hydrants to discover that they're dry. And so basically they tried as hard as they could with the city basin burned down. And they found afterwards that somebody had closed the valve between the city reservoir and the hydrants. The fire department hadn't checked that the equipment worked and the South Yuba Canal Company or Marsh and bases like, "Hey, this is your stuff, not mine. " It's like, "Who's to blame?" "Oh, both of you, frankly. " So Marsh's pond today. So we have Marsh's pond, so that was the first city reservoir that was built for the fire protection. They added a second one down below that's now the baseball field. But that's what that looks like today. So with that, I hope I've just given you a few little stories about Nevada City's history. So I think we only talked about, actually probably only talked about five digits. There's a hundred up here and I've written about quite a few of them. And if you're interested in them, first of all, thank you for all of you that have been showing interest and involved in my book. I very much appreciate it. I think you realize it's like, while selling my book is a great thing, I think you realize I'm not trying to make money out of it. So that's wonderful. But what I wanted to do is I want to share all of this history with you. So the website in vaudacityhistory. com has all of the maps. So all of the maps that are in the book and all the maps that you've seen here. So if you can go in here, you can actually just choose your neighborhood and actually just drill down and see, "Hey, are there any old mines here?" There's 3,000 mines that are actually, you can show up on here. There's a mine everywhere. But along with that, just where it's been hydraulic, so you can see the lidar data. It just pops out anywhere in places where it's been hydraulic. And then if you've got a ditch going through your backyard, if you live in Willow Valley, you probably have a ditch going through your backyard. Jeffrey lives in Willow Valley. Hi, I assume they've found that Jeffrey's address and they're like, "Okay, I can tell you the two ditches that go through your yard. " So if you're interested in hearing more about stories, go check out the website. Have a look at the book. But if you ever have any questions, my contact information is on the website. So if you want to ask me about any questions about this, follow up. I'll come look at historical remains anywhere in the county. It's all super exciting. So with that, I want to thank you very much for your time and we'll answer a few questions. [applause] Have you traversed most of the ditches? Have I traversed most of the ditches? No. I know a few people who work at NID and some of them are perhaps former ditch tenders. And those are the guys that you want to congratulate and say thank you, particularly during the winter. But I don't know, I mean, so in doing some field research, I've plotted about 10,000 GPS points over the years. I used to say to my wife, it's like, "I'm going out ditching. " And being the golden retriever, they seem to just go out and, you know, looking for old ditches. So, yeah. John Spalding. They built the new dam to the tunnel to South Eubels in Elle to get water to the here greenhouse. Mm-hmm. Yeah, that's right. The comment there was Spalding put together, well, it was already on construction, but the lake that became named Lake Spalding into John Spalding's honor, he ran, who was the superintendent of the successor of the South Eubel Canal Company. And they actually had two, two goes at the dam. The later dam allowed them to raise the height of that to allow extra hydroelectric generation later. Without water, it ends up at the pulse point. That's right. Yeah, that's right. So you think about all of the water that comes down in the South Eubel Canal, it ends up today in Deer Creek and in South Eubel River or in Bear River, and then it comes up, ends up down in the back. Right here. So the question was, when did NID start? So actually, so I have, there's a chapter about NID in the back of my book. So NID started, people started to get idea about building an irrigation district during the, just around the end of World War I. But it took about five years until 1926 for NID actually to come together. And they spent years haggling and negotiating with PG&E. So the way that NID came into being was that essentially through eminent domain, they are able to gain ownership of all the water rights in the water to generate electricity. We would like some money, please. But it took PG&E negotiated for years and years and years before they actually signed the contracts to give NID some revenue, which then actually allowed them to start doing developments. So for example, building the Deer Creek reservoir, building the DS Canal, Chicago Park Canal, et cetera, getting more down to the South [inaudible] and that was, it was just through the relentless negotiation of all the risk that NID happens. Good question. So there's a remnants of Ditches up at Conservation Camp Road as you drive down toward Rock Creek and they kind of traverse that land heading down toward Rock Creek. Can you tell us anything about that through the DID? And if your answer is by the book, I understand. Yes, by the book. Go to the website. So what we've got here, so what we're talking about is, actually it's a little bit off the map here, but if you go to the map there, you will find the ridge ditch and the blue tent ditches go through there and they cross across the top of Rock Creek and they provided water primarily to blue tent. Okay. Thank you. Well, and then the ridge ditch is the blue one here, going all the way down, providing mines to the Harmony mine and so forth through the 1890s. Other questions? So you touched a little bit on the water rights, an existing water rights. So how did they work it out originally to the original water rights? You have all these companies competing. I mean, how did they work that out? So the question was, how did they work out the water rights originally? And the quick answer is they weren't very good at it and it usually ended up in court. So this is one of the reasons why the water companies often combined really quickly because they worked out or competing with lawsuits was pointless. So, so I actually had this, there's a, there's a whole chapter in my book about the lawsuit between Kidd versus Laird and it's even trying to take down Amos Laird. The South Yuba Canal Company were trying to prove that Laird was misusing his water rights. But the thing is what the South Yuba Canal Company was doing was they were stealing water upstream so that it looked like Laird had all the water and they used to drop it back down halfway down the ditch back into Deer Creek. So they could bypass all people's dams. So it's very clear what the water rights were, but they weren't interested in exactly what they were. They were interested in getting the water to where they wanted to go and then selling it. And every gallon, every minus inch of water that you had is an inch that the other person couldn't sell. And so they didn't get on very well. Yeah. A lot of money was made on gold, but how much money was made on some of our very good questions. So a lot of money was made on gold, but what about how much money was made on water? So if you go back to the owners of the South Yuba Canal Company, one of them died a millionaire. The others didn't actually do particularly well. So there was a lot of money that I frankly think went into very good lifestyles and also into very dodgy business investments. And so they made, I mean, so for the 10 years, 10, 50 years after the South Yuba Canal was finished, they were bringing in, it was about 80% margin business. So for every dollar they brought in, 27 costs, they were making a lot of money. But they then went into lots of different, so now kids paid for the construction of two different steam ships on the, to run between Saper system and Sacramento. Tens, hundreds of thousands of dollars going into these other businesses. So they took their money and they had very good lifestyles, but then they invested in lots of other businesses that didn't necessarily work out. Did ditches evolve into the pipelines around water with the main mines? Good question. So how did the, how did the old ditches evolve into the pipelines or actually the ditches that provided water for the hard rock mines? So there's a transition. So when hydraulic mining ended in 1884 with the SOYA decision, the South Yuba Canal Company had already switched its business market to starting SEL's hard rock mines. And they realized that investing in Pelton wheels, or in the Pelton wheel driven industries was actually going to, you know, was going to get there. They knew the, they knew the SOYA decision was coming, it was just fresh and it went. And so between 1882 and 1884, their South Yuba Canal Company's revenue dropped to a quarter of what it was. But as all of their hydraulic mining customers, it's all illegal. But by the following year, they were back up to about two-thirds of their previous revenue because they started digging new ditches and providing water to the hard rock mines. And they charged them at twice the rate that they used to charge the hydraulic mines. Now to Steve's question there, it's like, what, you know, how does, how does the, there was a new set of ditches. So the Idaho ditch, which went to the Idaho mine, the Cascade ditch, which was also dug for the Idaho mine, but then also later provided water for the Empire mine and North Star Powerhouse, for example. And so all of these then developed and they had more of the technology to do high pressure pipes. So they did ditches wherever they could, but then to cross ravines and just do an inverted cipher using a high pressure pipe and you could get to a lot of places. So it was really a development through from the late 70s until into the 1890s when the water was all about either the hard rock mines. Do you have plans to extend your research in further into South County? Do I have plans to do further research into South County? So I'm not sure about that. This, this is about, yeah, yeah. So, probably not. The maps actually extend out, it goes out, there's quite a few other ditches in a lot of different other places, but the depth of research they got into, it's quite time consuming, etc. I needed to focus somewhere, so if I even included too much about Grass Valley, it would be a larger book. They raised lakes all 40 feet, so you're talking about the Sondheim ditch. So the Sondheim ditch now comes down on the Diaz canal to the site. It goes across your creek. So you get away with the Sondheim ditch where you're showing the dam. That's right, yeah. So in 1972, they cut off the top half of the Snow Mountain ditch and they replaced it with water from the Cascade ditch going across the siphon across here. And then actually later the time they then rebuilt the Cascade ditch so that all of that was actually pipelined as well. So all the way from just the bottom half of Snow Mountain ditch is a beautiful old ditch and the rest up here is all dry and then even all of the section of Cascade ditch is all dry up here because it's all got replaced. But, you know, things keep on evolving. So after the hard rock mines, you then assumed steam and electric came in. How did that affect the waters? Yes, the question was how does steam and electric affect, you know, particularly the hard rock mines? Well, this is a really tricky thing. All of the hard rock mines, so they had hoists and they had the mill, basically the stamp mills and, you know, everything needed a lot of water power from comfort fields. So they all had a steam engine backup. But the thing is they realized that so literally the Idaho mine, actually no, excuse me, the Eureka mine, which was next door to the Idaho mine, literally closed in the 1870s because of lack of fuel for the steam engine. So by the 1870s, people talk about how the fact that it was clear cut from eight miles around the Idaho mine. So the closest lumber, closest timber that you get for fuel. So they needed something ridiculous. Like, come on, there's 20, 25 cords of wood a day. I mean, it's basically, it's three large trees a day in cords. And so they, you know, early on it's kind of like, oh, there's a tree over there, let's take that. And then the next year it's like, oh, it's a mile away. It's three miles away. So the the the hauling costs were just ridiculous. Eight miles. And so to bring in water, first of all, you can you can fire the two guys that run the steam engine. Right. So it's a pipe pointing at a pelton wheel. It just keeps running. You need somebody to turn it on and turn it off. And that's it. You pay for the water and you're done. And so getting water into power, all of the mines was a no-brainer. It was literally it was taking out, in some cases, a quarter to a third of the operational cost of the mine of switching to water power. And so when electricity came along, so during the early 1890s, they were all about electric lights. I mean, you know, the North Bloomfield, all that was was it was lit with arc lamps years before Edison came up with incandescent light bulb. So they were like North Bloomfield was night and day with arc lamps. So the problem is, is that electric motors weren't powerful enough to drive the hoists and to drive the other things. And so it wasn't until 1910 or so that mines started switching over to electric power because at that point, PG&E could provide reliable service. It was hydroelectric. And the motors were actually powerful enough to replace machinery in the mines. And at that point, Bordeaux was just used for steam backup and fire protection. I'd like to make one more question. So that was the last time that PG&E delivery allowed the service? Correct. Yeah, you'll you'll notice that my in going through my book, the comparisons of the fact that one monopoly of the South York Canal Company led directly to another monopoly that uses the same infrastructure. The irony and business there is not lost, believe me. There we go. (audience applauding) (audience applauds)