Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2023-02-16 - English Dam Disaster of 1883 with Juan Browne (62 minutes)

Weather permitting and the creek don't rise, by popular demand, Juan Browne from the world-famous "Blancolirio" You Tube Channel will provide a multimedia presentation for an evening of mystery and intrigue of the largest dam disaster in Nevada County History! Fresh off the heels of two years of reporting on the 2017 Oroville Spillway failure and rebuild, Browne uses his new found skills in water management to unearth the mystery of the epic English Dam Disaster of 1883 impacting towns as far away as Marysville and Yuba City.

Author: Juan Browne

Published: 2023-02-16

Original Held At:

Published: 2023-02-16

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

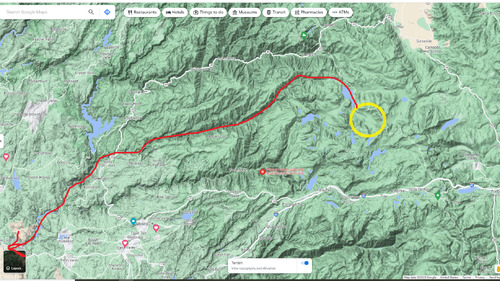

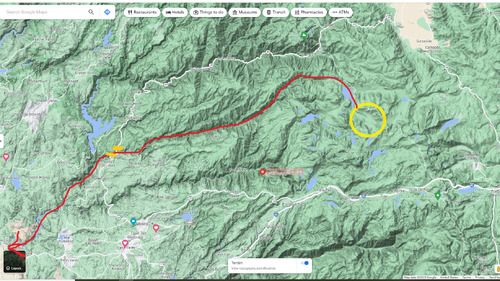

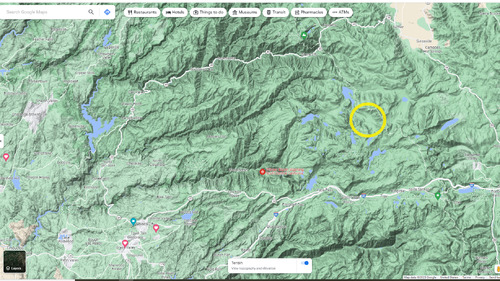

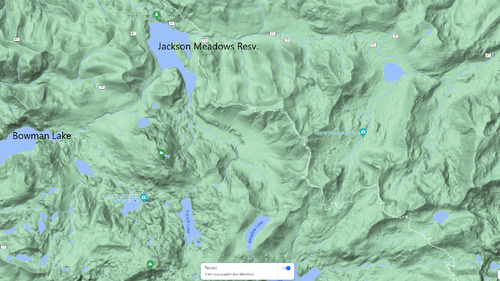

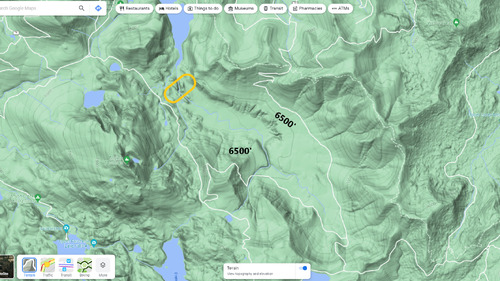

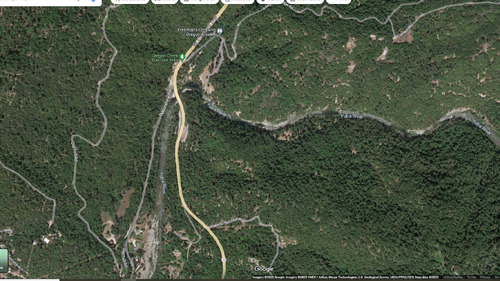

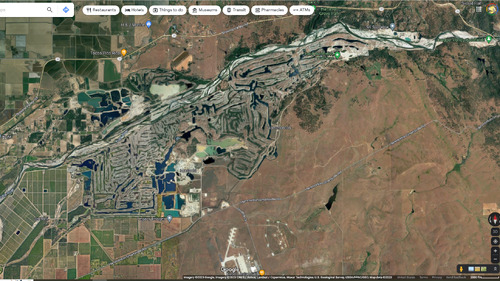

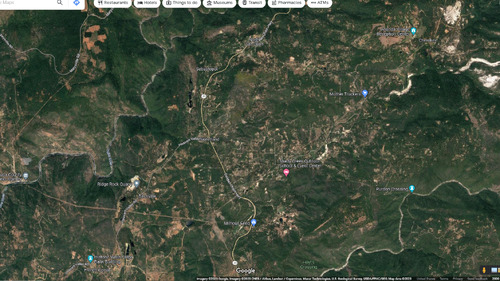

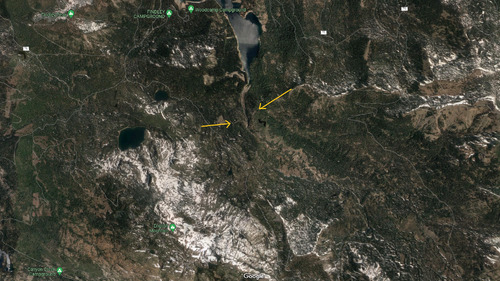

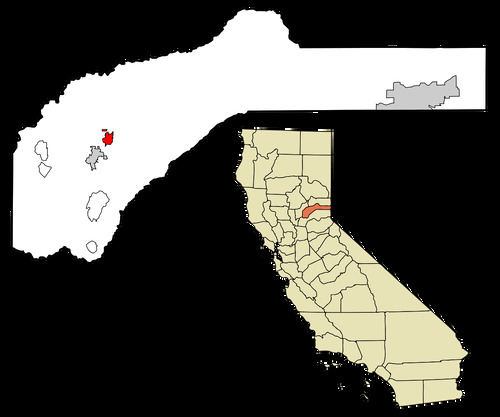

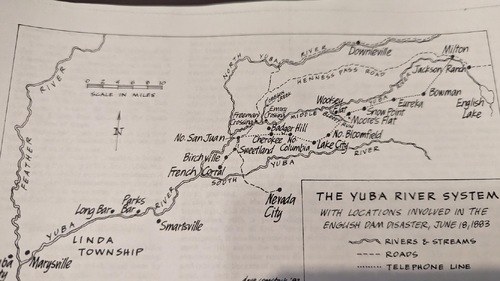

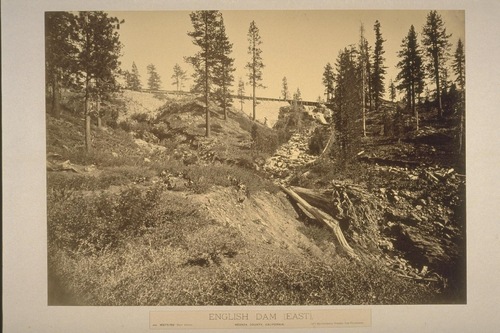

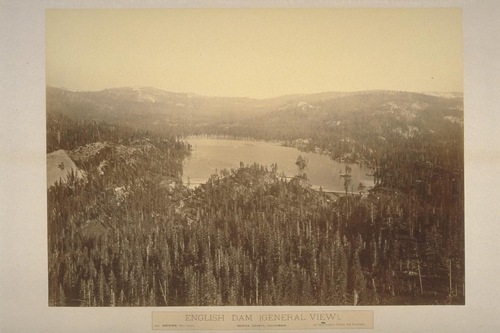

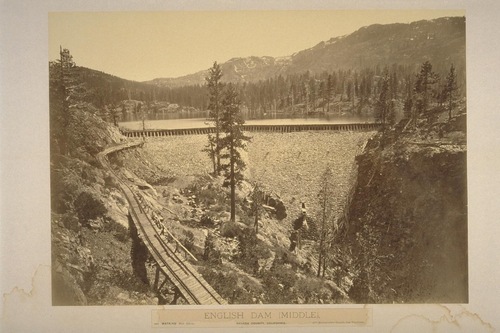

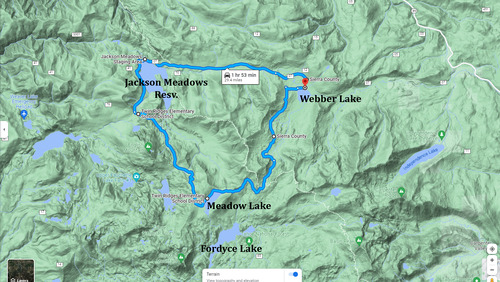

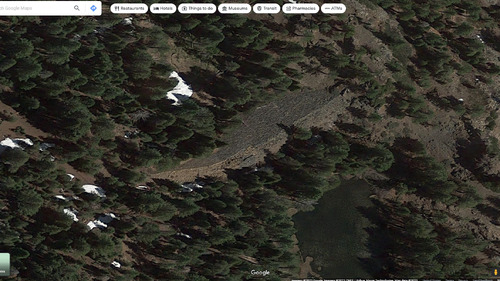

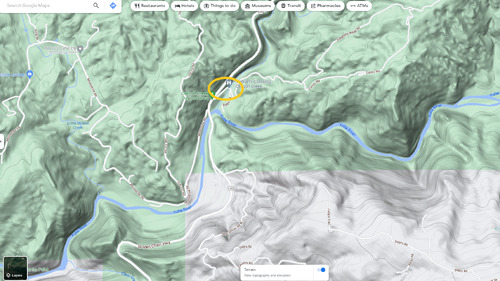

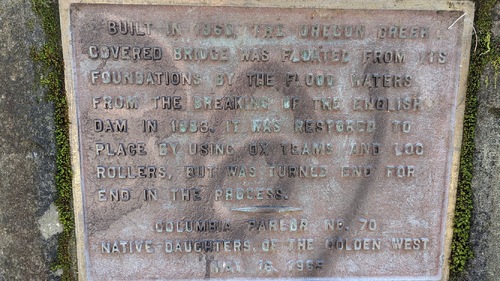

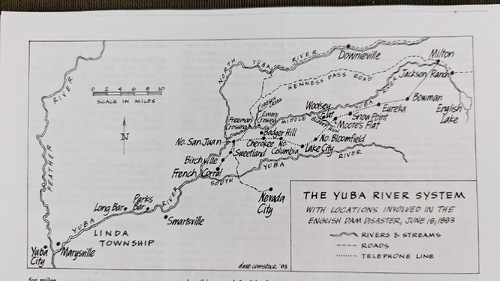

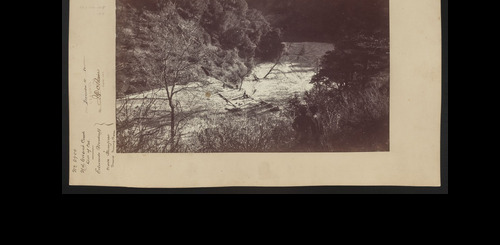

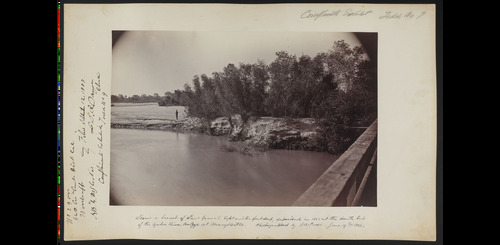

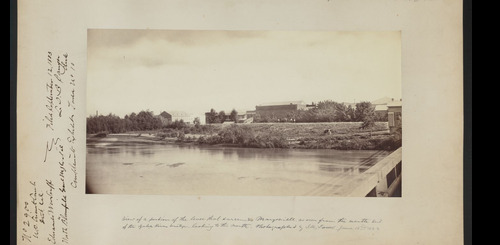

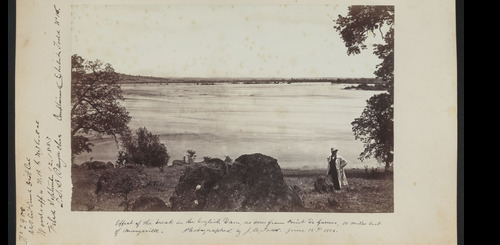

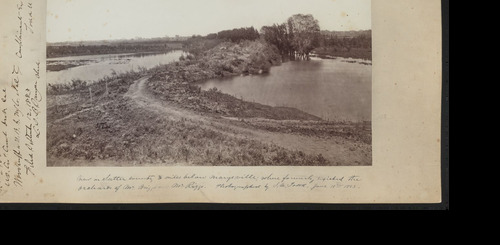

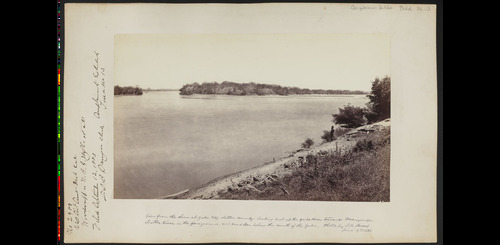

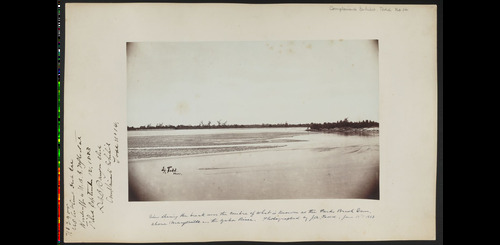

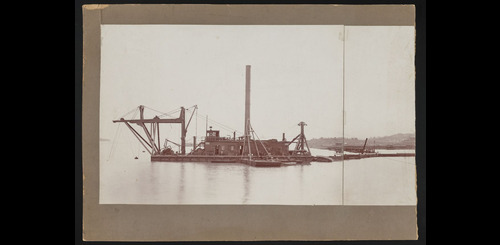

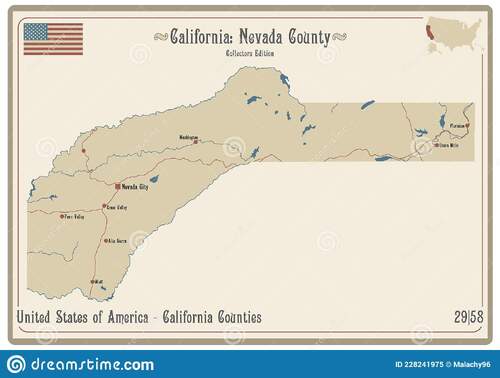

So tonight we have a, I'll call him "Plane/Reporter 1" Brown. And he would probably know one and have seen his works. He's famous on his own right for probably the coverage he did on the Orville Dam back in 2017. But I think his interest in history is probably genetic because his mom, Juanita Brown, a well-known author, published quite a few books. I don't know how many, but these are two that society published. And we actually have her sale in the nuggets of Nevada County. And this one is particularly popular. A tale of two cities and a train, which is an area of drillery. We have those for sale at the back table back there. But his father Pete also was an active member in the society. And like me, he served two terms as president back in the board of directors back in '86, '97. Hopefully we can maybe convince Juan to take a similar path. That would be nice. We have a good open position. PR is one of them. So we're kind of hoping maybe tonight's presentation might morph into a book. Videos quicker and easier. All right. Calling all stations, the English dam broke this morning at 5 a. m. Warned everyone along the Middle Yuba River. Such was the shocking news received from the stations along the ridge telephone line the morning of June 18, 1883. My name's Juan Brown. It's time for Uncle Lirio update on something that happened back in 1883. But it's a very important piece of Nevada County history that's worth going over. Dan already gave you the update on the family ties here to the Nevada County Historical Society. It's a lot of fun to be back here, one of my first presentations here at the Historical Society. It's going to be a multimedia presentation here, but I'm a one-man band jumping back and forth between here and the computer. So that'll be interesting to see how I get that worked out. And I've got a couple of special friends here I want to introduce. How I got interested into this story was through one of the hobbies I did that mom could not stand was riding motorcycles and riding dirt bikes through Nevada County. And folks from Nevada County woods riders, Fred is a member here. Any other woods riders here this evening? Good. Yeah, Eddie. And so these guys told me about this location of this. And Fred, you have a pretty good understanding of the history of this English dam. And that piqued my interest. And I went back several times since. And now I've spent some time down here at the Searls Library to actually get my facts fairly straight. So most of this tonight is plagiarized and the rest I'm going to be making up. And then some of this reading straight from the Union newspaper, which according to some folks Bruce here is mostly all lies anyways. Somewhere between all this, we should be able to figure out what the heck happened to the English dam in 1883. But it was a real important piece of brand new technology that made this this at the time was the second largest dam failure of a artificial lake in world history. But it was because of this brand new telephone line, the rich telephone system that there were only two fatalities as a result of this. So the first thing I want to do is go through a bunch of maps, because what drives me nuts about history is I can't figure out where are we talking about where is this stuff located. So we're going to start with a map of Nevada County. The boot, the gun shape of Nevada County, the upper portion here, this is the northern portion of Nevada County is the middle fork of the river. This portion down here is the Bear River right in here is the area we're talking about. This is the location of the present day Jackson Meadows reservoir and the location of the original English dam reservoir. So going to Google Maps, pulling up the terrain, there's Nevada City, there's Grass Valley, there's Bullards Bar and up in here the Grouse Ridge area. Here's Jackson Meadows reservoir in this valley. Here is the area of the English Dam. So we're way up in the high country at about the 6000 foot elevation. So when this dam failed, this water poured right straight down through of course Jackson Meadows reservoir was not there, it was the ranch. Past Milton reservoir, more about that on a second. And all the way down the middle fork of the Yuba all the way down towards Marysville and Sacramento and impacted areas that far away. Along the way on this journey tonight we're going to be talking about the Oregon Creek Bridge which is located right here and Freeman's Crossing located right here, very near where the present day highway 49 crosses the middle fork of the Yuba or the middle Yuba. So here's Jackson Meadows reservoir and it's in this bowl here that the English Dam was located. To get to the English Dam is a little bit of a challenge. It's a good, it's a great adventure bike ride or dirt bike ride, and it's a challenging four wheel ride. The easiest way to do it is if you can get to Jackson Meadows and then take the Meadow Lake Road, a very rough four wheel drive road towards Meadow Lake, and then you can get to the dam through some ID property just off to your left here. Very rough, slow going up here in Meadow Lake. This is the historic Summit City, and then this part of the dirt road is in pretty good shape. It's pretty easy ride or drive for this section, but this section between Jackson Meadows and Meadow Lake is terrible. The dam itself is located was located in a three part series down right about here. And if we turn on the Google satellite view, you can begin to see the remains of the old English Dam. So this would be the west side sometimes referred to as the south side down. This is the east dam over here, and the middle one is gone. And that's right along the middle fork of the river. Middle river. Here's a closer view, east and west. So these rock remains are still there and are in remarkably good shape for the east and west side. And of course, the one in the middle is completely gone. A closer look again at the west side, a little bit of water left behind there. And when you get up close to this, it's a remarkable bit of rock work that makes this smooth face to this dam. They had a rock quarry about a quarter mile away where they were able to obtain the rocks for this. And on the east side, it looks like there's still some indication of a sort of a spillway slot here. Further downstream, we're back here at the 49 crossing of the middle Yuba. So here is where Oregon Creek Bridge is located and Freeman's Crossing was located right about down here. Off the old toll road and moonshine. I think this is the footings to the old Freeman's Crossing. Now, even further downstream, here's Beale Air Force Base. This is an important part of the story. How this deluge did not take out Marysville. Right about along, where is it now? Right along here, DeGere Point and DeGere Dam. Well, I don't think DeGere Dam was there at the time, but right here about DeGere Point. This portion of the levee along the Yuba River failed during the English Dam disaster. And so that relieved the pressure. There was a 40 foot wall of water reported upstream of here. And as it hit this area that weak farmer's levee failed and poured seven miles worth of water out to the south towards the Beale Air Force Base. So that by the time the water headed towards Marysville, it was just a matter of about two feet of water rise. And by the time the water headed all the way down to Sacramento, it was less than a foot of water rise. But in the Yuba River Canyon, there were reports of as high as 75 to 100 feet of water in the narrow canyons. Here's North San Juan area just kind of showing you a current view of where some of the evidence of some of the original hydraulic mines were that this whole operation was supporting. Down here at the Ridge Rock Quarry, right over here, right over here, and then up here by Cherokee. And that's the whole idea of the Old English Dam is an effort to support hydraulic mining in this area. So let's see, let's start with a couple of current day videos. Where did I put it? Here we go. Debris flow. Have you guys ever seen what a debris flow actually looks like or seen these videos online. Here's a modern debris flow from Utah, the desert of Utah from a thunderstorm. When the debris starts flowing, it doesn't look like water, it's just trash, it's trees, it's rocks, it's solid material moving in a liquid fashion. Houses, cars, bridges. That guy's parked a little too close. And as it widens out and spreads downstream, it just looks like a living thing moving downstream. Yeah, like lava, and it'll just crush everything in its path. But this is a nice wide area here. The reports from the English Dam were that, well, by calculations, from 6,000 feet all the way down to the valley floor and all those miles, it moved along at an average of about 10 miles per hour, this debris flow. But it would get blocked up and then unblocked and moving in fits and starts like that. Now let's look at a very hazardous, narrow, this is like a mini example of what it's like coming down a narrow gorge. This is in Switzerland. Look out, grandma, it's coming through. And it starts out as just dry material. Now watch this house, this tree, and this car. There goes the car. That's going to hit this bridge and get blocked up a bit. Look out, mom. So that's a view of how fast and how destructive even a small debris flow can be. And then it's just solid after that. Okay, hydraulic mining. Does anybody need a refresher on hydraulic mining? Everybody knows how that works. Where was that? So the key to hydraulic mining is water. You need lots and lots and lots of water. And the trick is you need the water to run these monitors. And the monitors basically got a Berkeley jet movable nozzle on the end of it. And so you balance this cannon with a load of rocks on the back and timber. And then with the rod that he's holding there, you can move the nozzle left and right and that steers the entire cannon. And with that, you can wash down the entire mountainside, but it takes 16,000 gallons per minute to run this monitor. So huge amounts of water. And it's all done with water that's gravity fed via pen stocks from a higher elevation. So that's why it's profitable for these miners to create these reservoirs and build these 80 mile long ditches, in this case, the Milton ditch to get to the diggens to run these water cannons. So that's the whole objective. And then, of course, what do you do with all the water and slickens once you're done with the mining? That's the problem. And that's a problem at the time of this dam failure that was brewing big time between the farmers and the ranchers and the miners. A couple of quick sites along the way here. We're going to be talking a little bit about the Oregon Creek Bridge. This was just taken yesterday. They've restored it and put it back on its foundations, though backwards and it's been well restored. Milton Reservoir we're going to talk about because this was the end of the telephone line. And this is where the beginning of the Milton Canal started here at Milton Reservoir today. We're looking at it right here. This now feeds the Bowman Lake Diversion Tunnel, which moves water from the Ubo River system into Bowman and through another series of water works, moves water all the way to the Bear River system. And it's this tertiary gravel that the miners are after. This is the ancient riverbeds that has the fine gold in it that can be easily extracted using the hydraulic mining method. Freeman's Crossing today is marked by one of the historic tea posts from the Trail Association. So this piece of technology of the Pacific Telephone System is an interesting part of the story. So you've got all this water. You've built this. Let me show you that Milton Canal real quick. That's what I wanted to show you. This is another amazing engineering feat. The Milton Canal. So at the Searles Library, they've got this wonderful Errol McBoyle map that folds out on the canvas that Pat will let you look at and take a picture of. I took a little video of this. Errol McBoyle would take this map to investors to show them what Nevada County has to offer. And on here, this is a map from about 1900 or so. Here's the English Reservoir. Here's the Ubo River. And here right about here is located the Milton, small Milton Reservoir. Great fly fishing there today. And this is the beginning of the Milton ditch. 80 miles long. It could move about 2800 minor inches. Here it gets mixed up a little bit with the Eureka Lake Canal, the miners ditch. But works its way north of the Bloomfield diggings. All the way down through Columbia Hill. Sugarloaf. All the way down to Sweetland. So that's the whole objective of this reservoir is to convey the water from here to there. Now in order to run that water, especially during the summers when it gets dry, they needed a way to turn the water on and off quickly. But it's too far away. So with the help of a few guys named Bell and Edison and a few folks like that, they developed the world's first telephone system. Not a telegraph system, but a telephone system. And this system had a series of boosters. Each of those dots, by the way, this is a great map from Dave Comstock. He drew it back in 1983. Dave did a lot of work with my mom on the books and illustrations. So each of these booster stations were located basically a battery to help boost the signal. Because here's how this thing worked, this telephone system. From the records on Earth, it was verified that the Milton Mining and Water Company built the line and spent exactly $4523 for its construction. Now this wasn't the only telephone line. I think there was another telephone line that the North Bloomfield Company used as well. They used number eight iron wire on 25-foot cedar posts costing $7 per mile. Edison instruments were rented from the Goldstock Telegraph Company of San Francisco at a rate of $20 per year. Now they say these boosters, that's the dots along the way, 14 of them, consisted of six quart jars hooked together. From records available, it was determined that the quantities of manganese, salimonia, bluestone, and zinc were used for the solution. And through the solution were passed the telephone terminals or wires. So those were crude batteries enough to keep that signal strong enough to go all the way the 60 mile long track from French ground all the way up to Milton. So there's that gap in the story of communications between English Lake and Milton Reservoir. So now let's look at some pictures of the original, of the dam itself before, before pictures. Okay, so this dam, they start, somebody else built this dam besides the Milton mining company. It changed hands a couple times, but in 1856 to 1858, this was the original dam. It was a timber dam, or crib dam they called it. And so they hiked these, I don't know how the heck they did this, but they got the timbers down into this canyon. It's, that's a height of 79 feet worth of timber. It made a smaller reservoir than the one that failed. And inside of those timbers they filled with rock. It was a little leaky old timber dam, but it was a quick way to dam up the water to get the water they needed for mining. Then they began slowly improving the dam. And here's a general view of the overall works looking towards the east. So you can see all three wings of the dam. Here's the middle dam on the middle fork of the Uber River, the one that failed. And then the west wing and the east wing of the dam. Creating a much larger reservoir. This, at this time the reservoir is believed to be 650,000 cubic feet of water, about 395 acres. And about 131 feet in height from the, that would be the bottom of the middle fork of the middle roof. So on the west side of the dam, now here you can get a closer view of the improvements where they poured in the rocks, laid them in there real smooth. And again those smooth rock finishes are still there, but they laid it right on top of the old rotten timbers. And this is, you know, 1880s or so. And on the west side of the west wing of the dam was this maintenance or this shack here where the guard or maintenance crew would occupy to oversee the dam. And that's the part you can access. Today you can still find some nails and boards and some pieces of tin and stove pipe bits from that cabin at that location. You can still walk across this dam and walk all the way over to the middle fork. I'll show you in the video here in a minute. But I couldn't figure out an easy way to cross the middle fork to go look at the east side of the dam. It might be easier to hike in all the way from the other side of the whole valley. Here's the view of the east side of the dam, and I believe right here is a spillway works. So if there's one thing we learned in Oroville, in the Oroville disasters, I learned really quick, any time you have a earth-filled dam or any kind of dam that's not made out of concrete, if that dam is ever topped in any sort of way, it'll fail, and it'll fail suddenly. So you've got to have a way to keep the water level controlled and from overtopping the dam. So you've got to have a spillway that works, that keeps the water level under control and from overtopping the dam. And I think that's the spillway for this dam. We've got all those, yeah. Here we go, the middle after the rocks. And it looks like there's a box structure. This box structure I noticed was in the timber version of the dam as well. They're beginning to build a flume over here. But as they added these rocks on top of the old timber, they also built a new timber top to the dam. And this is the part that is believed to have failed first. So now let's go look at the video that I shot a couple of years ago, showing you what it looks like today. Get the volume browning. 1883, right here in Nevada County. The Trustee Mule, the Yamaha XT225. We'll take a little flight right over the middle port, U-Hoe, where it failed. It just scoured it out completely. There's no evidence of the original dam left in that. It was like that about two hours after the dam failed. Rugged, steep country. The drone is really the only way to get in there and take a look at it. Okay, we're almost there. Down the street there's Jackson Meadows Reservoir, the current reservoir for this watershed by Nevada Irrigation District. And down there is the middle fork of the Yuba River. Yeah, right up here should be what's left of the old English dam. And there it is, right over there. The broken part, the middle part, the main part, that was almost 250 feet tall. There's what's left of the dam. There's the part where it blew out right there. And right up here is Old English Mountain, the namesake of the dam. And back behind there is was the reservoir is now just back to English Meadow and still used for cattle grazing even today. Here's some old timbers, some of the old square nails of the original construction of the dam. What a neat spot. So you can still see just the walls of the sides of the dam left over there. This thing failed on June 18th of 1883 at approximately 5 a. m. The watchman had a place clear on the other side of that ridge, so it took him a while to realize what was going on and come find out. It only took an hour and a half for this entire reservoir to drain. This is about the 6,000 foot elevation, the top of this dam. And this dam was 250 feet tall down to the bottom of the Middle Fork River, about 130 feet natural water causing massive destruction downstream. The mystery is what caused this dam to fail? The original construction of this dam was a wood crib dam. There's a reason they called the gold rush a rush. It was a rush to get the money, get the gold. Everything was done quickly. Of course, there were no codes or anything like that at the time that I know of. So dams like this were built quickly using timber, a wooden box built with logs. They later added this dam by adding rocks, the rocks that you see here today. Apparently they were working on the dam, improving it from its original wood design to a rock design when this thing failed. I believe the point where this thing failed was still a log dam. What was the spillway outlet for this structure? I know there's some ditches on the other side where they conveyed the water down to the gold fields down below. Of course, the whole idea of a reservoir like this was for the hydraulic mining. Hydraulic mining required enormous amounts of water. A single water cannon, like we saw the other day at Malikoff, could use 16,000 gallons per minute. And so they had to dam up as much water as they could to run the hydraulic mines. Today, this water system is all part of the Nevada irrigation district for providing conveying water downstream for drinking and agriculture. After the gold rush, companies like the Nevada irrigation district performed to convey water to farmers so they would no longer have to make this long run like I saw today. The cattle of the cattle up here in the high country, they could just convey the water down to the low ends where the cattle were and water their cattle all year round without having to do this long drive up into the high country to get into the green grass. That's what these reservoirs were used for and still are used for to this day after the gold rush. But what caused this one to fail? There was talks of sabotage. There were numerous other dam incidents in the local area that had been a product of sabotage. People getting burned, not getting paid for all the hard work they did in building the dam. And of course, there was the controversial Sawyer decision putting it into hydraulic mining. And there were farmers that were very upset with hydraulic mining. They could have very well had a motive to wreck such infrastructure, but it was never ever proven. And from the looks of what's left of this dam, and by the date of June when this thing is plump full of water, I believe in the construction that was going on at the time, I think this dam just simply failed. No sabotage. So as soon as the dam failed, shortly thereafter, the Milton Mining Company put out a notice for a reward. The Milton Mining Company and Water Company offer a reward of $5,000 for information that will lead to the apprehension and conviction of the party or parties who caused the destruction of the dam of the Milton Mining and Water Company on the 18th situated on the headwaters of the Middle Yuba River. But no suspects were ever uncovered. So now I want to read some first-hand account information. This is the plagiarism part of the presentation. First, I've got a really interesting thing here from Richard Toll, a childhood friend of mine, Union Hill School, son of Dick Toll and part of the Toll brothers, somehow related logging company years ago over there now to California. The Technical Society of the Pacific Coast Institute, April 1884, article on the destruction of the English dam. And they explained how they were working on the dam, adding additional rocks to the rotten old timbers, and then they came to a point where they wanted the rocks to settle in to the timbers, and they added that new timber section to the very top part of the dam. Now here's a good first-hand account of the day of the morning of the break. "On the evening of June 17, 1883, the dam, as was the daily custom, was examined carefully by the men in charge and reported to the superintendent that everything was in perfect order. The gauge that evening showed the level of the water to be within 16 and a half inches of the crest. " So it's June, the dam's plumb full. "The gates were open, delivering water to the ditch, with nothing running over the waste way. " Well, so it wasn't completely full, but it was darn near full. "The following morning, at half-past five o'clock, the watchman making his early inspection heard after crossing the south dam," everybody's got to traverse that whole ridge there, "when within 300 feet of the middle dam, two violent explosions, one reaching a point where the main central dam was upon reaching a point where he could see the central dam, the water was seen pouring through an opening in the upper timber work, over the crest of the stonework, and through the gauge at the south dam showed that it still required two and a half inches to reach the waste way or high water level. So this dam failed just two inches below the spillway level. " So just two inches from plumb full. "In a few moments, the crest in the center of the dam, the rock crest, for a length of 175 feet, was swept away, and an immense," I'm sorry, that was the timber crest, "and an immense opening soon cut the dam to its very foundations. In the space of one hour, fully 600 million cubic feet of water were discharged into the canyon below, at a rate of 166,000 cubic feet per second. " That's about the maximum flow you would want to flow out of the spillway during a high rain event. That's a massive amount of water. That is some of the higher flows that you would see even coming into the Oroville reservoir during high rain events. Now let's move over to the Pete Vander Pass English Dam Disaster article he wrote here in the Nevada County Historical Society Bulletin in 1983, celebrating 100 years. So we'll pick it up right after the, well, the water leaves the English Dam. Now what's the watchman going to do? There's no telephone connection up there. He can't outpace the water to tell anybody else, so the water's just moving downstream. At about three miles downstream from the dam, and you kind of follow along on the map there, was Jackson's Ranch. This is before Jackson Meadows Reservoir. The farmhouse, quote, "took passage for the Sacramento Lowlands before the first wall of water. " The Black brothers who were operating the farm got up early that morning and were able to save themselves. A visitor who inspected the site later reported seeing only two chickens where the farm once was. The union wrote that the bottom land is strewn with trees and parts of trees smashed in all kinds of shapes in many places, pieces of the trunks of trees, two and three feet through and eight to twelve feet long were peeled of all their bark as clean as could be done with an axe. And some trees 100 feet long were uprooted and peeled of all their bark and limbs. Those that saw it say that large trees, when they went down, would roll over, end ways, roots up, then tops, and smash to pieces. The whole bottom around the Jackson Place is heaps of sand three and four feet deep, deposited far back from the river. Other places have been swept clean to bedrock. Then they moved further down the line. At Milton, where the water for the ditch was taken off, and this is where the telephone line is, another dam was destroyed and nothing was left of the flume for 30 rods, about 500 feet. It was probably from Milton that the alert was given via the telephone line. So the dam breaks around five and the reports are that the phone call was made about 730. Now, I don't think it took that long for the water to get that short distance from English Lake to Milton. Maybe there was that surprise factor. Maybe the guys were all running around wondering what the heck's going on. But eventually they got a phone call to all stations that the dam had urged. North of Eureka, by the way, you guys that are familiar with the Middle Yuba, it gets really narrow in here. You're familiar with the gates of the Antipodes and just how tight it gets. North of Eureka, the banks of the river are very precipitous and higher than anywhere else. Here the surface of the river was 100 feet above the low watermark. At this location mining along the river, the Reese brothers and an old man with his wife and two boys beside about 20 Chinese, one of the Reese brothers was swept away by the waters. He was described as quite decrepit. Efforts by his brothers to save him were to no avail. Initially it was stated that some of the Chinese drowned also, but it was found that that was not true. So that was one official, one of two official fatalities occurred right there. Opposite Snow Point, a tunnel for the Macillum's mine was being driven into the northern bank of the river. The drift was rapidly filling up and men who were working there would have drowned if they had not just completed an air shaft through which they were able to escape. Now let's go all the way down to Freeman's Crossing. Freeman's Crossing was kind of a big deal at the time. There was a hotel, a blacksmith shop and a toll bridge. The bridge at Freeman's Crossing was 200 feet long in four spans resting on piers 15 feet above the water. Freeman had built the hotel and a commodious house for himself and a blacksmith shop and a broom factory. Freeman was warned for the coming torrent by telephone at 8 o'clock in the morning. Now in another account, there's no phone at Freeman's Crossing, but there was, they did get the message obviously to North San Juan, a short distance away, so a messenger on horseback was dispatched to tell Freeman about the dam break. The water reached Freeman's at 9 o'clock, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, so some what, four hours later? So it's moving along at about 10 miles an hour. Again, the Union Road. Pine trees two feet thick were uprooted by the wall of water and came roaring down the canyon at the rate of 10 miles an hour and were hurled forward end over end until they were splintered and completely stripped of their park. Nothing's even capable of withstanding the raging torrent after one stop fairly started down the steep grade that the channel has in the mountain here. Here and there, the logs were pushed along the front of the first big wall of water and would become wedged in between the steep banks and refuse to concede the right of way. That's that 90 degree bend in the Yuba River right there near the present day 49 bridge. And then more logs and brush would come along and pile up in company with them. And what seemed to be an unbreakable barrier of debris 100 feet high, reaching clear across would hold back the torrent for a few moments. Then when a roar and a crash and a rush, the obstruction would be beaten down and the flood would proceed on its course of destruction. Soon Freeman's house had two feet of water in it. A log washed into the house. Later, it needed six men to carry it out. The blacksmith shop was demolished. The 200 pound anvil was never seen again. And the broom factory was damaged. And a large number of brooms ready for shipping were carried away. Now, another accountancy judge, O. P. Stigger, the editor of the San Juan Times, was on the stagecoach, which had just crossed the bridge minutes before it collapsed. He described the incident as follows. Before the stagecoach reached a point a quarter of a mile above Freeman's house, the roaring of the mighty waters gave notice that the flood was close at hand. The stage had then reached a point where the passengers had full view of the river. The bridge and Mr. Freeman's house in a few minutes, in a few moments, the flood came in all its fury, pushing, tossing, whirling in advance. A great black mass composed of tree logs and driftwood of every kind of description and a perpendicular height of at least 30 to 40 feet. So that kind of matches that description of some of those debris flows we were looking at in the videos. Viewed from our standpoint, it was the grandest as well as the most terrific sight the mind of man can conceive of. The water roared like a thunder and moved at the rate of at least 10 miles per hour. At just 25 minutes before 10 o'clock and just seven minutes after the stage, with its load of passengers crossing the bridge, the structure was carrying away. The huge mass of driftwood struck the middle pier, which supported the bridge and carried it away. Unless the minute thereafter, the bridge was afloat, and a minute or less after that, it broke into two pieces and was carried down the river with other driftwood logs and trees. When the driftwood stuck, the center pier was carried away. At the same moment, the end of the bridge at the Yuba gold side swung around, and in a moment thereafter, the whole bridge was afloat. Now the Oregon Creek Bridge, it's located a little upstream from the middle Yuba. It's a short distance from the Yuba itself. But when that logjam come around that corner and stopped briefly, that water started backing up. And it backed up so far up the Oregon Creek that it pushed the Oregon Creek Bridge off of its footing upstream. And it went upstream a ways, then that logjam broke, then the Oregon Creek Bridge floated downstream all the way back down to just about the middle of the Yuba River and stuck there. So they were able to recover the Oregon Creek cover bridge and put it back on its footing, but they got it on backwards. They just couldn't get it turned the right direction, but it seems like a pretty straight bridge to me. So, let's see. Somebody saw that bridge go too. He said it tossed it just as light as a feather. So this 40-foot wall of water is marching on downstream, and it's sure to hit Marysville and be a huge disaster. But back into the technical publication here, they explained how the levee failed, thus relieving the pressure off of all that water. In descending the river below Point De Gare, a poorly constructed levee on the south side of the Yuba gave way, and a large volume of water poured through the breaks and passed over some seven miles of farming country, thickly settled. In the midst of harvest, resulting in the destruction of some $4,000 worth of property. So, from a 20-, 30-, 40-foot wall of water, by the time it hit Marysville, the water level only went up about two feet, and by the time it hit Sacramento, later that day, it was only a foot or so less. So, they've been fighting the ranch, the valley farmers and the miners have been feuding about this slickens. They've been collecting data on it, and this was the final straw. They just had it after this. So, a guy named John Toll was documenting all this by photographs. And here's the photographs that he submitted to the, what was it, 9th District Court of California while fighting the, it was the, the Sawyer decision was the lawsuit between Woodruff versus the North Bloomfield Mining Company. So, it was the folks that were running Malacoff diggens that were getting sued. As a result of all this, the Milton Mining Company, which was profitable, they're bust now, they're just completely broke, they're out of business. So, let's start right here. John Todd, up here on the left, it says 9th Circuit Court of California, 1882. So, this is the kind of debris they're dealing with in the Feather River prior to the English Dam failing, and this is what they're collecting as evidence to fight the miners in this lawsuit. And it reminds me a lot of the Greenhorn Riverbed with the pile of, the piles and piles of debris. In an effort to try to trap these debris or keep them from becoming a bigger problem, they put these little crib dams in there, but there's really no technology that I know of today to clean that stuff out other than a dredge. And these waters are unapplicable anymore, you can't get a dredge up there to clean them out. So, this is all prior to the dam break. I mean, what are you going to do with all that material right there? A broken bridge, here's the Malachoff diggers who they were suing at the time, working away, and now we got June 19, 1883, the day after the dam break, and again John Todd is out there photographing it, and this becomes evidence during the Sawyer decision. Here's the Marysville Bridge, shown the erosion on the side. Here's the levee at Marysville, which fortunately was saved by the levee break upstream. Here's farmer's fields that are completely inundated. Here's what it looks like at De Gere, a point near the present day De Gere dam, seven miles of water washed down towards Beale, saving Marysville, but inundating all that farmland. And this, they're saying is below Marysville, these orchards getting wiped out. This is on the Marysville levee. Again, after the dam break, parks bar after the dam break, De Gere point again, somewhere along the river, and of course the whole thing is becoming unnavigable for ships to get up to Marysville to ply their trade. So they did have a way of dredging these waterways to try to keep them navigable, but it's a big expensive operation. And of course, later the Yuba goldfields moved in there where the levee broke and all that water flooded. That's where the Yuba goldfields are located today. And they did successfully gold dredge or dredge that for gold for many, many years. So where does that put us? Back to here. So the next year, the Sawyer decision comes down and we all know how that went. It did not go good for the miners. The Sawyer decision, it didn't say you could not go hydraulic mining, it said you cannot throw your stuff in the river. You cannot put any more debris into the river. So hydraulic mining did attempt to go on for a few more years, especially with the help of this telephone line. Though the Milton company was out of business because of the dam break, the Malecoff tickets could continue. And they worked on some technology to try and grab the gravel and not send it all downstream, some elevators and try and make some spoil piles to limited success. But as inspectors would come to inspect the mines, they would be warned ahead of time with this telephone system and they would shut off all the water and send the miners home and show the inspectors that little or no mining was going on. Every time the miners came to town, they'd go over to the union and tell them, don't tell them we're in town. And the first thing the union would do is the next day put a big front base article saying the regulators are in town. So they were able to do some hydraulic mining after the passage of the Sawyer decision. And to wrap this up, it's a very eloquent letter to the editor written by a farmer farmer I H Hogue of Marysville, praised Judge Sawyer in his article from the Sacramento Daily Union dated February two 1884, that of the editor. It is true that twice within the last 10 years in consequence of the filling up of the riverbed with hydraulic mining slickens, I've been compelled at large expense to boat my cows off my place to save them and have suffered great damage from the loss of crops and some source, still knowing that the right would finally triumph. I had held to my farm and by perseverance made it productive and valuable. Now I would say to the hydraulic miners, do not be discouraged if you cannot use water to wash down the mountains to make them give up the gold that is in them. Try some other process that will not hurt our farms in our valley. We will give you our best hopes are encouraging good cheer and you will succeed and you will have double satisfaction that comes from success. That is not secured at the expense of a brother's failure. The large water reservoirs in long water ditches that have here to force applied the power to wash down the mountains will no longer be needed in the change system of mining, but they are not there for dead property. So things changed. We got away from hydraulic mining. We instead moved to the industrialization of hard rock mining and we still and we created one of the single largest economies ever. So that's my side of the story of the English dam. Questions and corrections. We can open it up for now. So did the built in company get sued by people that got damaged? You know like Freeman. Well, Freeman was industrious and he got his bridge back in place by fall of that year. I don't know that he sued him. I don't think there was any blood to squeeze out of that turnip because I think they were instantly from profitable to bust. So I don't think they got sued. It was the they went after the deeper pockets. I think of the of the Malacop because the blue gravel company. They were done for him. So you have any idea of the size of the sand? I was thinking about that looking at those pictures and she compared those rough numbers of the acreage. I think it's a bit smaller. It's got to have been a bit smaller than the present day Jackson Meadows reservoir. So I don't understand how they can go after the Malacop diggings company when the Milton dam broke. Because the that company had a separate set of reservoirs. They were using Bowman reservoir and all those reservoirs to keep their minds going. So they weren't relying. They did own that reservoir for the the Malacop did own the Milton or English dam reservoir, but they sold it to Milton and instead that developed the Bowman reservoir. You go back to the picture of the rock face with the flume on the left side of the old picture or the modern day picture. The one right before the broles. Oh the flume. Yeah. Yeah. OK. I know what you're talking about. It'll. Right there. Yeah. That's actually for more parts. OK. So that's the the quarry. Right. That's how they got the actual got in. OK. Excellent. So they mentioned a quarry that was a quarter mile away where they were quarrying the rocks. So this must have been how they got there. They said something about a tramway. So maybe this is part of the tramway across the top of the dam to get those rocks to where they wanted to go. Excellent point. Not a flume. You don't put the flumes on the top of the dam. Right. Glad we got some experts here. So from the access to this type of photo. To the top photos. Yeah. I found them online. Yeah. Yeah. They're a little bit of a challenge to find. But I can try to get you the link. In fact I was trying to find them again today and I was struggling. But they are available. They're preserved through a California history site. Yeah. Hey Juan why would you say that the dam was not sabotaged when the the caretaker heard two big booms. I think those two big explosions were those timbers failing. That's what I think. If you talk to any old timer including the black family. Yeah. The camp pass go was a relative of the blacks who were there. They are all 100 percent convinced that it was divided by the farmers either by the farmers or by a group of people hired by the farmers in the valley. Yeah. That could very well be the case. Monday morning would be a good time to do that. It would be so early that they never found anybody. How are you going to get out of there quickly too. I mean I suppose you could ski down across the east side and go up the valley that way. And I don't know if they had time to charges in those days. They probably just had to set off and run like hell. One more quick point. The idea was organized by farmers on ranges. It was dry agriculture and so you were real dependent on the seasons for your crops and your orchard trees. It was like earning beer wagon and a lot of those guys that were farmers. The ranchers still had to take their cattle up. Yeah they're still running the cattle up there today. Yeah. It's all annual grasses. They're going to grow up far and die. You can't water dead grass. It was farmers that originated. And that would be all the farmers that we see down here in Chicago Park and these elevations. One of the primary originators for the NID. Yeah. He had his daughter. And today NID is working on preserving the area. Calling it English Meadows. They're working with the Forest Service and South SP and some land trusts to try to preserve that area and improve the water shed above Jackson Meadows Reservoir. So hopefully we'll still have public access to English Meadows. We'll see. Let's get one minute. [applause] We're going to fact away the history about this. Soil your decisions generally are regarded as the very first environmental protection decision in the U. S. at that point. That's a lot of precedent. Secondly, how many of you have taken a woodruff cut off when you're going to Warville or so? No it's farmer woodruff. It's property. That is a good point. You simply planted in that case. You'll remember that every time you make a woodruff. Well it's great for some refreshments. Hope to see you next month. [applause]