Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2023-11-16 - The Historic Sluice Box with David Lawler and Hank Meals (67 minutes)

Nevada County Historical Society is pleased to present David Lawler, geologist and Hank Meals historian, speaking on "The Sluice Box": The most commonplace gold recovery tool of the 19th century.

Included will be a slide show presentation on the sluice, a gold recovery device that was used everywhere in the mines. And, recently, an “atmospheric river” revealed a sophisticated streamside sluice that’s been buried for over 150 years. The sluice has provided a lot of information on 19th century mining techniques, and it has been salvaged to soon provide an exhibit for the Nevada County Historical Society History Center. Don’t miss this resourceful adventure story.

Included will be a slide show presentation on the sluice, a gold recovery device that was used everywhere in the mines. And, recently, an “atmospheric river” revealed a sophisticated streamside sluice that’s been buried for over 150 years. The sluice has provided a lot of information on 19th century mining techniques, and it has been salvaged to soon provide an exhibit for the Nevada County Historical Society History Center. Don’t miss this resourceful adventure story.

Author: David Lawler and Hank Meals

Published: 2023-11-16

Original Held At:

Published: 2023-11-16

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

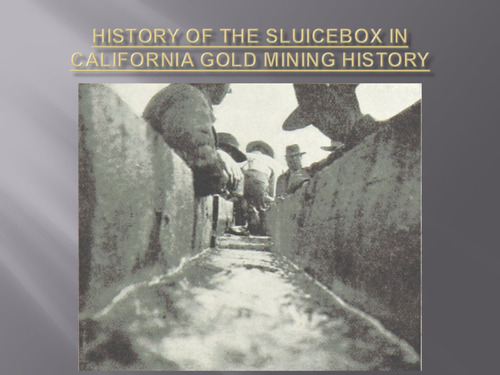

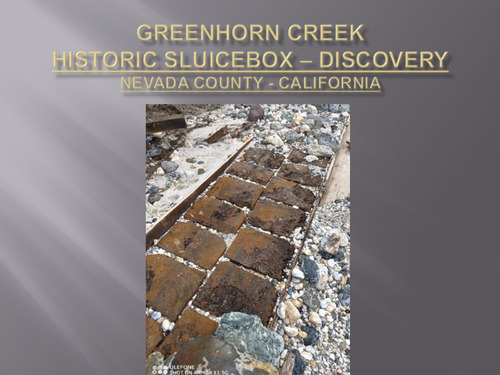

We have geologist Dave Waller speaking to us, but first up is our geologist Hank Meals, who many of you know and around here forever and ever. [laughter] There you go. You ready? 50 years. Why are you still with us here? Great. You're on. Are we on? Yeah. Grab the microphone. All right. Let's see. I need to be able to see this. Where am I going? This is the right question. Can you hear me? Yeah. Good thing it sounds good. All right. The way this goes is I'm going to talk for roughly 25 minutes, and then we'll have five minutes or so of questions, and then Dave will talk, and then we'll have time for some more questions. I love this photo. I just had to have it for the poster because it's the only one I know of where you get a view of a solution from the point of view of the gold itself. [laughter] This is from 1519, translated from Latin, and it's a tin mine, I think, in Bavaria, and it's in the beginning of almost every book you'll see on gold mining techniques. It just shows you that people were aware that gravity can be used to transport and cut with water. This is the basic sluice box. It could be a long time. There's a little bit of hair splitting. Let's see. If it was a long time, it would have a hopper here, which is like a box with perforated plate in it, and it would be the first level of separating gravel. Basically, you could see what a sluice is. It's a rectangular box. It's set at an angle. They're generally 12 feet long nesting, so the end of this would be a little smaller than the entry side so that they can be pieced together. We wind up, eventually, with sluices that are thousands of feet long in certain hydraulic mines. In the case of what we'll be presenting today, the tail sluice can be several miles long. One thing that you have to maintain about a sluice is the angle. It's on a slight incline, and something else to be said is to enhance the recovery of gold since it's in such a minute level. By the time it gets to the end of the process, you have to introduce mercury, or mercury. This is a basic sluice box. What more can you say? That's pretty straightforward. The interesting thing is, the sluice box is part of most, other than chemical recovery processes, it's part of every mine in operation today. The guy out there with the suction dredge, or just moving up from a pan, the next step you get to, you'll be using a sluice. This is the sluice and how they operate it. The fundamental rule is the more you move, the more you get. This is a ground sluice. Essentially what you're doing in ground sluicing is you're tapped into some ore that has gold in it, and what you're doing is picking away and using pry bars, you're essentially creating erosion. In the in-net sluice will be small obstacles called ripples, which can be transverse cleats, they can be flat rocks, they can be logs, I mean not logs but rounds. The idea is that as the ore in water, it's a muddy slurry at that point, as it crosses over the gold because of its specific gravity, should drop down in between these obstacles. Then you have a cleanup at the end of the process to recover the gold. Now I was really lucky to find this. This is essentially, this is Timbuktu Bend down here, so Smartsville would be up here and Rose Bar would be down here. This is sort of an idealized version of Buzzard and Jerusalem, but it's that big beautiful bend on the Yuba. What it shows pretty well is, this is I think 1856, but you can see the water inlet over here, it's just a simple ditch and it contours around the hill, and what you can barely see are these perpendicular lines, which are essentially sluices going down to the river, so that's the way it works. This just shows a tremendous variety of, well, and there are many, many more. Gold appears in many forms, and what we have here are lots of variations on sluice boxes. There's nothing you could really read up there, but the whole idea is to just show you that there's a tremendous variety of sluices, and to this day they're experimenting with ripples and looking for something that will recover all the gold. Here's the basic principle. Water and the slurry containing the ore is flowing around this way. This is a ripple, a little obstacle. This is a cross-section we're looking at. You could see that the water goes over the ripple, makes a little turn, continues on, but the heavier material, which should be black sands and gold, are dropping behind the ripple. This is North Bloomfield, and this is on a grand scale. What you can barely see up here is that there are monitors, pressurized water, water cannons, that tear away at the cliffs, make the cliffs drop, they drop down into the pit, and then often they have an additional monitor or water cannon to just push the tailings along and toward the sluice boxes. Here's the sluice box itself. These are all coming from different sources, but all winding their way to a singular sluice. A lot of hydraulic mines, like on San Juan Ridge, Columbia Hill, had a couple of 2,000 foot sluices, there were many places with lots of sluices. Here's a diagram of the ditch system, at least a flume. What's backing up the whole, this is all water and gravity power, the whole process. When you look at, say, a hydraulic mine, the mine is much more than just the pit you're looking at. It's keyed into maybe 50 miles of ditch with all the various appliances that go with that. And then there's a drain tunnel at the end of the process, and then after it leaves the mines, and the miners no longer care, it went down into the valley, and they did care. So eventually they put it into such a flamboyant style of mine. There's a sluice that's paved with wooden blocks. Now, what's unique about these is they last a while, and it's really the spaces in between these blocks, where the gold's going to drop as the slurry goes over it. And here's a bird's eye view of the same thing. Here you can see the blocks. Here's a cross-section of the blocks. This is from the North Bloomfield drain tunnel. Here's a sluice that's used rounds where they just cut through the tree. And again, it's the spaces in between that are collecting. Well, a clean-up consists of, which is periodic, and it happens at different intervals of different mines, and different kinds of mines, but you would take all this material out, and take that material and process it, and even finer check it. This is Columbia Hill. It shows the process. These are definitely sluices. Now, this is down around Smartsville, and the mines there were big and productive, hydraulic mines, and this wagon, and you almost always have a stamp mill as part of a larger mine, or you have an arrangement with, not a stamp mill, a sawmill. So, these are blocks being delivered. There's a whole sawmill that is, what it does is make these blocks because the bigger ones, they last eight to ten weeks. Now, here's a drain tunnel to something that's unique to the northern mines. The northern mines are those mines that eventually flow into the Sacramento River. The southern mines flow into San Joaquin. What happened in the northern mines, since they were more hydraulic mines, is this phenomenon called a drain tunnel. So, here's the edge of the Malacob pit up here, and you have to get rid, as you're hydraulically, you have a problem of accumulating tails, so much so that you can hardly move around in the pit that you've created. So, you want to get rid of those, and if you're getting rid of those, you might as well, and you're going to push them down slow, you might as well use that opportunity to add another sluice. So, in this, and so they had sluice tunnels. So, this is up high. Here's the river down here, actually. So, they put a, well, in this case, it's like a shaft, and this is a tunnel. This is all underground, and it comes out down here on Humbug Creek, below the falls. These are probably the falls right there, on Humbug Creek. This is, this particular drain tunnel is over, it's over 8,000 feet, and it was really hailed worldwide as an engineering marvel. It was created by each one of these shaft, these little marks here, and they worked in both directions, around the clock, to produce this. Here's a cross-section of it. And really, I've said this before, the ability of water conveyance systems, hydraulic gain, was really refined in this area. It was really the equivalent of what Silicon Valley was, in a worldwide context. All the lines around the world looked to North Blingfield, Nevada County. Could you speak up a little bit, better? Okay, thank you. Alright, so here, oh, just wanted to show you up here is the Malacoff pit. Here's the shaft I was talking about. Each one of these was accessed, all of these are along the trail, the Humbug trail itself. This is the same place we looked at in the painting. This is Timbuktu Bend. This would have been the mountain top. We were kind of looking at it from this angle. Well, the point of this is to show that each one of these little vertical marks here is a drain tunnel. All of this goes into the river, and all of that goes down into the valley. Here's a drain tunnel, at the Boston Mine near Red Dog. These are riffles from the drain tunnel at North Blingfield. Those started out as one inch by about six inches, iron. They were all this wide, and they get battered in the process of acting like sluices and have to be replaced periodically. But I think that's a pretty good illustration of the tumultuous battering they take. Now here we are down again, near Rose Bar. This is Timbuktu Bend again. These are tail sluices, the very last sluices, after it leaves the mine. You can see, here's the edge of the tailings. You can see that they have to keep building the sluices longer to be able to fill it. Because when it hits this level, it's flat, and so it's not dropping, and the gravel's not moving away. That just gives you an idea of how the lower main fork of the yuba, the main trunk of the yuba, was completely choked by gravel periodically. And here we go again with just a 1930s style mining operation with the sluice again. And if somebody was to set up a sluice today, it'd probably look very much like this. There we go. Any questions? Thank you. All right, we'll move right on to Dave then. I've got a question. Yeah? So what was the quicksilver and mercury used for? Which it used for? Yeah. It has a. . . Let me have one. It binds with really tiny particles of gold. Gold that would ordinarily go right over the sluice. So it has a. . . I don't know that anybody has really broken this down chemically to talk about how. . . We're talking alchemy here. We're still. . . it binds and forms an amalgam like the dentist uses for your tooth. And then it's heated in a closed system in a retort to separate the gold from the amalgam itself. Does that answer your question? It's kind of mystic, but. . . Yeah? Hank, if after the first 800 yards of the sluice box, it could probably get most of their gold out of that, how much more would it get for another mile of. . . Yeah, you're right about most of the gold recovered there, but still you're losing a tremendous amount of the gold. And it's relatively inexpensive to. . . You're having to channel the material out into the mine anyway to build the sluice. Could you speak to the volume of mercury that used so many metric tons, do you think, in California? I don't think. . . More about that. Okay, thank you. I'm going to move over to Dan. Yeah, I think you need to let my talk on the laptop. Yeah, we think the estimates are 100 million tons of mercury were used at which 30 to 50% were lost. So there's 50 million tons between 6,000 foot level of Sierras and the mouth of 6,000 foot level of. . . Did they eventually use cyanide? No, not for placermine, not for placermines, free gold. Why not? That was. . . All in hard rock was cyanide used. Why couldn't it be used in placer? The point of using cyanide is to liberate the gold particles from the quartz. And in this case, through 20 million years of tropical weathering, the gold was already released from this bedrock source in the gold quartz phase. So I wanted to showcase the discovery of a 160 year old artifact that I found in 2016 after 35 years of working on Grand Harm Creek for a client as a geologist. Never did I think that where I had walked thousands of times that 30 feet below me, under the tailings, was an intact sluice box system a thousand feet long. And so we'll move on here. . . So the Egyptians had the discovery of King Tut's tomb. The Scandinavians have Viking ships buried. This is the equivalent of that in Nevada County. And as Hank and I have talked about many times, to find a mining processing artifact made of wood that's 160 years old, that is in nature, is almost virtually unheard of. The only reason that this length of sluice box system was preserved was because it's been under water for 160 years. And I want to very quickly go over these key points before my talk briefly. That this sluice box represents a very poorly understood period in California history. We know a lot about the gold rush, using very primitive, as Hank has pointed out, very primitive sluice boxes. We know a lot about the advanced stage hydraulic mining period starting industrial scale in the 1870s. And the extraction and hydraulic mining of this ancient Yuba River channel, which was the largest and oldest ancient river system in the world. And this all happens in Nevada County. Nevada County has more gold production from placer gold than any other county in California and in the west. It was all due to the establishment of this ancient river channel, starting in the ancient dinosaurs and going through the tropical period to about 40 million years ago. But this sluice box system was specifically designed for the hydraulic mining of tailings from hydraulic mining operations. And as Hank has very clearly pointed out in his talk, there's a whole variety of sluices. And each one of those had its application. And the sluice box that we found has extremely, it was very, very sophisticated for its time. And even in terms of its contemporary nature. The burial date, we're thinking, might have been the flood of 1862, the largest flood in California's history. The burial depth, we estimated 150 feet. Greenhorn Creek filled up at least 150 feet to 175 feet from where the miners were mining during the gold rush in 1849 and 1850. The duration of the burial was about 160 years. Only in 2016 did I see the top posts of the sluice box standing out in the flood. And every four feet for 200 feet. The sluice box construction, as I pointed out, was extremely sophisticated. The incredibly efficient utilization of local timber resources, particularly old growth. The best grade of lumber you could have. The sluice box design, it was designed in modular units. Each unit is 12 feet long. And there's at least, we found 25 units preserved that was exhumed by the last year's floods between January and March. It was a double sluice. It was two 6 foot wide sluices divided. It had a center dividing board. Each one 3 foot. So you could get double of production per day, per week, per month. And its total length, we estimate, at 900 to 1200 feet. And this also has solved a 30 year mystery as to why Greenard Creek is the most polluted, mercury polluted watershed in western North America. We estimate that in South Yuba there's about a mercury load of about 5 to 10 kilos of mercury. So 10 to 20 pounds coming down every year. In Greenard Creek it's between 200 and 400 kilos. Almost up to 1,000 pounds a year. It's traveling down into the watershed, into the Bear River, and then of course into San Francisco Bay. So this is, we fortunately, at the archives of the Nevada County Historical Society's Searles Library, Hank and I found this photo of them actually mining the, exclusive the hydraulic mine tailings. And how they're doing this, it doesn't show in this photo, but I think the next one it does. You can see a plume of water here that is actually pushing the tailings down the flute box. And that's how they were able to move a vast amount of material. Their only trick to this was the quantity of mercury they used was for every 1,000 feet of flute box, they were using per site 10 pounds of mercury per linear foot. So for every 1,000 feet per year they're using 2,000 pounds, a ton of liquid mercury per 1,000 feet. So the gold here is very, very fine. It's smaller than the size of salt in a salt shaker. And again, why did they go to this amount of trouble to develop a whole industry mining tailings? And everywhere you see on the map this gold is a mining district. And there's so many mining districts that it all adopts coal less together. But the main reason here in Nevada County in the Sierras was this vast tropical river system that basically went from the southern tributaries near Lake Tahoe, the northern tributaries near Susanville, the confluence of both the southern and northern with San Juan Ridge in the vicinity of Malecof and then flowing west to a giant delta on an empty tropical ocean here on, so the beach would be in this area starting about 60 to 40 million years ago. And so this river system is the size of the upper Amazon around where you've been is the channel, the Paleo Valley is over 4 miles wide. That's the width of the upper Amazon today. It's so wide that when you're at the Amazon in that area it looks like a giant lake, but it's flowing downstream at about 15 miles an hour. So fast that it's almost impossible to canoe up the river. So this was when they were finally able, not during the gold rush, the gold rush they identified what they first thought was a glacial deposit, then an oceanic deposit of gold. And they finally, of miners being empirical, practical people, determined that through looking, finding fossil leaves and vast petrified forests, that it was actually a river system. But most of the area we see here was really not, particularly the upper part, didn't go through the sluice box on the photos that Hank showed. That was just piped off. They hydroliced it, they shut off their sluice boxes. To them it didn't have enough gold in it to make it worthwhile. Only if it didn't get to the red zone, and particularly the blue zone, were they very keen on gold recovery. And then here, San Juan Ridge, this could be almost any ridge looking towards Lake Tahoe. In this case, the South Fork Guba, but we had this vast amount of gold-bearing gravel between what we call the divides. San Juan, you know, Japlyasine Ridge, Washington Ridge, and the river system was preserved, dissected by river canyons. This is what it would look like 50 million years ago here in Nevada County. This is the greenery, those are 200 foot tall hardwigs, with a two to three story understory under that. And again, if you went down to Marysville, this is what it would look like. So bring your Hawaiian shirt and your flip flops. So this slide is important because we are talking about sluice boxes. So I want you to pay close attention to what the gold loss is here and how that translated to the type of sluice box that you could build. For large nuggets, only a five percent loss, roughly. Small nuggets, ten to twenty-five percent. Fine gold, as I mentioned, salt, size, and down, almost a hundred percent. So when you look at, when you add those up and you look at what the size classification, most of the gold coming out of the San Juan River, which was well over twenty million ounces, that's forty billion dollars today, that was recovered, went out the sluice box, through the sluice tunnel, and then down to the equally awaiting hydraulic tailings. So this is, this size of daggert, you know, a ten year old could put together a sluice box and catch that size of nugget. That's the idea. You don't need one of these sophisticated sluice boxes. This is from the Ruby buying gold mine collection of a hundred, hundred and thirty nuggets that's on display down in Los Angeles County. Now from Sierra County. This size, this is the ten to twenty-five percent that they lost. Again, this isn't what they were catching at Greenhorn Creek. Still too coarse. That was caught up four hundred feet in elevation above the creek. This is what they're catching, this size on down. And why it's silver is because the gold is so fine that it's been amalgamated. And amalgamation is, again, it's a physio-chemical reaction. There's only, in our universe, there's only one or two elements we know of where a metal is liquid at room temperature and that is mercury. And not only that, it has an affinity that no other elements do, that when it is in contact with a piece of gold, there's a physio-chemical reaction that bonds to it. And you can take a puddle of mercury and you can have a handful of iron filings and you can throw it on that puddle of mercury. It will not break the surface tension. You take from elements starting like lead, in terms of specific gravity, lead's thirteen, twelve, thirteen, that will break the surface tension. And any, and particularly gold, silver, platinum, will adhere, it will break the surface tension, and then it will absorb it and it will continue to absorb gold particles until it reaches that boundary between being a liquid and a solid. And then when that happens, it becomes a solid called an amalgam. That's what we have here. So most of the finest gold in here, you can't see with your naked eye. The finest gold in this river that they were, that even they didn't catch in the sluice box system we found, is the size of women's cosmetic face powder. It floats on the metal. So here's what we recovered from a sluice tunnel. We took out two hundred yards and we recovered three pounds of liquid mercury from a hundred and fifty years ago. So it was just two hundred feet of one of these sluice tunnels. So without them having access to mercury, none of these, the hydraulic mines would have been a total loss and unprofitable. Again, so now I'm talking about, here is a, sorry, this is a smaller map, but here's Scotts Flug's reservoir. Here's the location of Greener and Creek. There's only two tributaries to the barrier. Here's Greener and Creek and here's Steepe Hollow and here's Lake Rawlings. And here's 49 coming up. And then it's in this area that this sluice box was found more specifically for those of you that are locals, if you've driven out. Red Dog Road to Buckeye Road going to Buckeye Flat. And then across. Here is Buckeye Crossing right here. And here's Gas Canyon that comes down from Quaker Hill. And these are the mining claims I've worked on for forty years. Here's an aerial drone shot. Here's again Gas Canyon. This is the area right in here, from here to here, where we found the artifact, particularly this part, in 2016-17. Here's a much closer shot, again showing one end to the other. It's still buried in tailings as of this date. So the site discovery really was multiple years, as more and more have exposed, over six years. Here's the hydraulic line tailings. This is what we call Mesodil Row. It's over 130 feet of thickness of tailings. That is why they couldn't have had developed this type of industry were this vast volume of tailings not available for processing. So this is in 2021. We, I was able to, Hank and I were able to identify. This is the bottom section, downstream section, of a 300 foot, we're looking upstream, a section that was still under 10 feet of gravel. When you ask Mother Nature to do something, she's really, don't expect her to do what you want. I told her, the beginning of this year, just take a little bit off. And I'll leave. So what she did instead, was she took off all 10 feet and destroyed 23 of the 25 units, washed it downstream, leaving only two of these modular units that was intact. And here we're looking at, these are the runner boards, okay? That's the foundation of the sluice box. Why did they have to have that? Because they realized after working on Grand Orange Creek for 10 years, that if you had a flood, that sluice box was heading on downstream. So they had to figure out ways of stabilizing it, in place where it wouldn't get washed away. They were not expecting the flood of 1862, which washed out every bridge between Mexico and Oregon. That's how big a flood it was. So here it stripped away the size of the sluice box. It left the runner boards because, we'll talk about why even this amount survived. And again, you can see, these are the cross ties, every four feet, that are holding the bottom of the sluice box, sort of off of the runner beams. And again, you can see the cross ties exposed here, just as they were from 160 years ago. Here's one of the areas that the rooflet blocks were left, exposed. And here's another one that is a complete set on the long side. This is only half of it. There would be a mirror image of this to the right. But the spacing, what Mother Nature did do was, fortunately, leave it intact, just as if they had walked away from it. These, I want to talk about some of the sophisticated key features of this. Here are these dowels, and those are holding together these 12 by 14 planks, logs, that were hand-in, and tying the whole thing together so it wouldn't wash out. Here is, again, more doweling, that was put in holding the bottom of the sluice box, or the bottom boards, to fastening it to the runner beams. Here, there's actually intact square nails. And here's a closer view of the square nail, which is now rested, put horizontally to make sure that the spacing between the sluice box, rooflet blocks, was maintained. Why? That was the whole object of this industrial enterprise. You have to have adequate room for pouring in the liquid mercury. So if you can imagine, everywhere that this gravel is now, was filled with liquid mercury. And so they needed a freight wagon of mercury flasks, probably monthly, up here. And they wouldn't have gravel like this in it. It would be, when mercury is in there, the gravel doesn't stick. It just goes rolling right along. It can't break that surface tension. That's how dense mercury is. Again, I'm just showing you the close-up. This is an excellent view showing how thick these rooflet blocks were, because there's a tremendous amount of abrasion. And that's why Hank had mentioned they have to be replaced so often. It's like a continuous electrical sander that's at all times working away on the surfaces of the wood. So the mercury was in here. So about once every three months, once every three months, or so quarterly in the year, to I would say quarterly, they cleaned up. And they got a lot of gold. And you know how with miners, even today, and probably in the universe in the future, there's the official production, and there's the unofficial production production. Why is that? Does anybody like to pay taxes? No. So I'm sure a lot of that was, everything, remember, had to be sold to the U. S. Mint. You were required to. And so, however, they didn't exactly have treasury agents running around in the hills then, but they had to show some production. But I'm sure there is quite a bit of gold off the books, shall we say. So recently, as in on Labor Day, we got a group of dedicated volunteers to go out there to recover the last set of sluice riffle blocks. This site is on Forest Service property. So the Forest Service has kindly donated the artifact to the historical society. And we had to get up there before the local thieves had plundered the rest of it. And it's a $2,000 fine to drive in Greenhorn Creek now, which used to be the four-wheel-driving capital of Northern California. But here's the crew with our carts, since we're not allowed to use motor vehicles. We had to haul them up there about half a mile, and then load the blocks into the cart about 22 blocks per cart. And here's Hank dutifully pushing the cart along the bottom of Greenhorn Creek. And Eric is pulling it as not as easy as it looks. We finally got them into my pickup. And then over to the historical society next door to the armory. And that's where they're waiting to be, along with the other compounds, reassembled into an outdoor sluice box exhibit, of which we hope to be breaking ground soon at that point. So Dan will talk a little bit to that issue. How much gold did you recover from the dispatch line of the blocks? Well, some of Grass Valley's finest have already helped themselves to that. So I would say probably for every gram of mercury they got, they probably discharged an ounce of mercury back into the watershed. So that's the problem, is that there's vast amounts of mercury still there. And that's going to have to be cleaned up hopefully before this next round of atmospheric rivers happens. But I would say, again, we noted it, duly noted, and then we didn't have an opportunity, shall we say, to answer that question. Please. This is being brought up into the air and out of water. So you don't have to preserve it to do it from deteriorating. Mercury is an element. Its elemental form does not deteriorate. No, but I mean the rocks. On the wood. So the wood, I'm sorry, yeah, so the wood was, most of this wood, particularly the side boards and the bottom boards, looked like it had just been cut at Cubich Mill a week before. Any wood underwater has been underwater for 160 years, 200 years. Looks just like the day it was cut. But now it's started to dry out. There's cracks that have developed. But fortunately, particularly with these blocks, with a number of them, where there has been cracks that have developed, we think we can glue it back together. But it's, you know, oxygen is taking its toll on it. But it's still intact enough that we can reassemble two units, each 12 foot long, and make an outdoor exhibit next to, and place it with Dan's capable help here, next to the Armory Building. And I want to thank our volunteers. I want to thank the Forest Service for their five years of, we had COVID in there, but it took them five years to get an agreement signed that it would come to the Historical Society. And, yes? Do you know what this one is? One second. Where did they count the Mercury? Where did the Mercury come from? The Mercury came through 329 mines between Santa Barbara and Crescent City. California is bluster cursed with world class Mercury deposits. If they didn't have those deposits, and if they weren't, started to be developed during the Mexican period in California, hydraulic mining would have never been successful. Mercury, the application of Mercury was absolutely essential to the economic success of both the hydraulic mines as well as the hard rock mines here in Nevada County. Is it correct that Mercury came from Santa Barbara? Yes. Mercury occurs in two forms, over near the geysers in Lake County. There's, the reason I got into geology was at eight years old I was in a tunnel over in Lake County on a very, very hot day. And I was in the mouth of the tunnel, and the entire tunnel, there was thousands and thousands of Mercury droplets sweating out of the tunnel and then going into a rivulet down 10 or 20 feet outside the tunnel. It was absolutely fascinating. The other way it can form is in this Oxide Form Santa Barbara. Right now at the geysers field in Napa, in Sonoma Lake County, they recover about 500 pounds of Mercury a year as part of their geothermal operation. It's a microscopic form, it comes up with the superheated water. So it's part of California's history. There are no known commercial deposits of Mercury in the Sierra. So all of that 100 million pounds of Mercury, liquid Mercury, was brought into the Sierra over a 75 year period. What is mental-related Mercury? When this legacy of Mercury, for instance, is deposited in anaerobic or oxygen-free environment, a group of microbes called sulfate-reducing bacteria, attack and metabolize that Mercury for, that's a breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Their waste product is methyl-Mercury. It produces methyl-Mercury that is the organic form of Mercury that can bioaccumulate in everything from bacteria, water skeeters, banana slugs, all the way up the food chain to us. So, yes. In the process of getting the amalgamation, what do you do about the other metals that are heavy and like gold? How much does that interfere with the recovery gold? What really interferes the most is that while Mercury is the quintessential element needed for gold processing until within the last 10 or 20 years, if it gets coated with iron oxides, the miners in the 19th century call that, "Oh, the Mercury is second in our box. " What they had to do was take out all the Mercury and then very, very carefully heat it at a very low flame and very carefully put in manganese in there. Because if you do it quickly, you're going to blow yourself up and everybody else in the neighborhood will blow it. So you have to do it very carefully and that removes that thick, that thin layer of basically iron of rust that has been deposited into the Mercury. So once the Mercury is freshened, as they use the term in the 19th century, then they can reuse that Mercury again to recover the gold. So again, as I said, the other components like these heavy mineral concentrates, those other elements, those other minerals that were in there, were not attached to the amalgam. Oly lead, and there is some naturally occurring lead here in Nevada County associated with these deposits, platinum and silver. And most of our gold here, compared to the state of Nevada, is very high in gold. So maybe we have anywhere from 5 to 15, well at least 15% silver. But other districts here, we have gold that's 90% pure. There's no nugget on earth that's 22 carat or 100% pure. They all have alloys in it of one kind or another. The gold, the Mercury little particles will attach to that gold. When you get the amalgam and then it goes to the refinery, then at the refinery by remelting that gold, they have the opportunity to remove those impurities. And most of the time they don't save the silver. It's not worth the effort. You go out to Nevada, you go to a gold mine out there, usually there's a very high percentage of silver. They have to recover the silver to make it the mine economic. Okay, this way. Can you talk about what happened geologically regarding this was more of a tropical environment a few million years ago and what happened to make it happen? What were the plans and the colors? The meteorite hit the Gulf of Mexico at 65 million years ago, changing for the next 60 million years the planetary weather climate on earth. And what it did, it created instantly a greenhouse effect that lasted for the next 20 million years. So here in Nevada County we have a tropical rainforest like we have in the Isthmus of Panama and the Colombian rainforest, Amazonian rainforest. If we went up 50 million years ago to the North Pole, we'd have an unbroken oak forest. No ice. That's how different it was. When that asteroid hit, it really totally changed instantly our planetary weather. And who would think that it would create a greenhouse for 20 million years? And that was the great, the tropical flora came within a million or two years. It was absolutely astounding how quickly and how long it remained tropical. The reason we have this much gold in Nevada County, we can thank to this, is all ancient rainforest gold. That rocks do not last long at all when under tropical conditions. What do plants love the most? Calcium. So granite has high amounts of calcium in it. So the plants in the tropics, you look at the granite in the tropics, there's just not a hill like Paphtome. There's a depression because the roots of those plants are so actively going after that calcium that they will dig a depression in an intrusive granite body. What are the health risks to be in the first time of all, this week? Well, you know, mercury is a neurotoxin for women of childbearing age and children of age of five. It can severely affect the nervous system development. So a fetus. So if you're an adult, you don't have to worry about it. For women, I think they find that mercury can concentrate in umbilical blood up to 30 times. But it should, that's feeding into the infant or the embryo. So it is a serious problem if you're an adult. The most significant fish, mercury contamination are a large amount of bass. Any predatory fish that eats other fish. Do you don't see any warnings at the lake? I think there are. There was a Oejo, which is a state health agency, has been over the last 15 years posting it. When we started a mercury study in the Sierras, everybody thought all the mercury had washed down in San Francisco Bay. It wasn't a problem. So every reservoir we have that was made not for boating, not for recreation, but for impounding tailings in the late 1890s and even the way up to Inelbrite, now has high mercury levels in the fish. Thank you. Do you have a question? Yeah. The type of wood. The type of wood? Pine was preferred because it has a habit of what they call brushing up as the gravel goes over it, like the whisk broke, and that helps retain the bark of the goat. Are all of those blocks numbered? And when we put it back together for the display, will it be exactly as it was? I wish. About two weeks before that, the last wave of vandals had come up and had totally taken everything out of context. So there's an expression that I use when I'm working south of the border that applies here. Anything left unattended is assumed abandoned. So that's what happened. But we have enough to make it representative. We have all the blocks. At least they didn't cart them off and have a campfire that night. One more question. So if the flood of 1862 buried this, what else is buried underneath there? I think there's about 10 feet between there and where the bottom of the creek would have been in 1850. So that's a very good question. So we're thinking there might be--we're going earlier and earlier in time. So by the time we have another year or two of extreme weather, we might be finding gold rush artifacts from the early 1850s. Because, remind everybody, there's two places in the county, maybe three, where hydroclimbing started. And one of them was Buckeye Flat, which is a mile, half a mile from where we found this artifact. And so the early miners that had claims on Greenhorn Creek were considered an egregious violation when hydraulic mining started. And all of a sudden, their mining claims were getting covered by dealings. They didn't appreciate that, and that became a very early type of litigation in the county in the 1850s. They did get compensated, but probably not to the extent they thought they should have. So we expect there might be a potential for even earlier artifacts on Greenhorn Creek as the storms unearth more and more material of towns. Do you know if Hanson Brothers is making any attempt to remove mercury in their gravel pit down there? Well, you know, if you're running a commercial business, an aggregate business here in California, you don't want to do anything that might make your particular operation less competitive. Because sand and gravel business is a $50 billion business here in California. And so I would say they've done what is required. But most of the mercury that's causing the problem is, as I showed you in that vial, is not the mercury you can see, the amalgam. It's the size of the particle that's suspended in water that won't settle out for a month. You can't even see it with your naked eye. That's what's causing the mercury problem in California. [applause] So we started this process quite a few years ago, and we negotiated with the Foreign Service probably, what, two years? Because the Foreign Service doesn't commonly loan artifacts. It's not in their policy, really. So we spent two years before we had an agreement that I signed. So I'm on the hook for that to preserve and display whatever we ultimately put back together. We have an architect-designed, engineered, permitted display structure. That in itself took a period of years. That's good things to do, the big time. And then also has a budget. What are we going to spend to build that? Yeah, it's going to be $8,000 and $10,000. $8,000 and $10,000. So nothing's keeping construction anymore. So we're fundraising, and I'm a firm believer in leadership by example. I'm going to practice that right here tonight. So, David, I have a $500 check here for you. Big check. To start that fundraising process. Thank you very much. [applause] Thank you for matching the funds. So if you can help them match that or contribute towards that, please do so. We have several thousand dollars more to go. We have raised some monies already, and we'll receive donations in kind, we hope, and make this project ready to go. We're ready to pour that slab, and we can just get the funding to do so. So make that check table in the Vatican Historical Society, and we'll make sure it gets into this account and the project on its way. So I want to say also, about ten years ago, I was invited not to look at Hanson Brothers property. This is on Forest Service property. But Hanson Brothers had a similar, were you out there as well? Similar, was that any of the sluice? It's a three foot sluice. Oh, three foot sluice. Same thing. It emerged through storms, and was quickly being vandalized and all off. And so we were invited to look at it, and they eventually just varied it again. I don't know what the status is today, but. . . It's a storm, so thanks for listening. Yeah, so it's really something we need to preserve. And again, we're going to have this on display. We have movies, kind of rear video footage, movie footage, hydro-lock lining. So we hope to incorporate that into, by display, in the library itself, and you can all backline the library and see what it actually looked like. I just, I want to say one thing about, this is really an unusual event in an archaeological sense, because you're usually trying to preserve a site. But in this case, every week we would go back, the site would look different. So, it was essentially ephemeral. It was disappearing, it was being unveiled and disappearing before our eyes. So to be able to talk this up with a forest archaeologist, just to be able to record it, a slice in time, because what we recorded, when we recorded it as a site, has all been washed away or vandalized already. There may be more in the future, but at least we have something. We have a nice slice of what happened there. [ Inaudible ] Okay, Hank and David are going to remain up here for questions. We're going to break down for refreshments.