Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2022-05-19 - Nevada City Nisenan and The Artwork of Henry B. Brown with Tanis Thorne and Hank Meals (52 minutes)

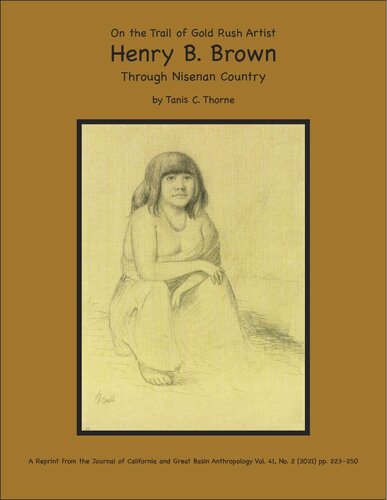

Tanis Thorne presented her research on the 19th-century artist Henry B. Brown, focusing on his drawings of the Nisenan people and landscapes in Nevada County, California. Brown's work is historically significant as it captures Native American culture just before the Gold Rush. Thorne's research involved piecing together Brown's travels using a map he marked, revealing previously unpublished drawings of Nevada City, Grass Valley, and the Yuba River. Brown's portraits of Nisenan leaders, including Chief Wima, are notable for their ethnographic accuracy and sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans. Thorne also discussed the challenges of preserving and interpreting Brown's drawings, many of which were done in pencil and have become illegible over time. Her work sheds light on a critical period in California history and the artistic legacy of Henry B. Brown.

Author: Tanis Thorne and Hank Meals

Published: 2022-05-19

Original Held At:

Published: 2022-05-19

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

So that's pretty philosophically weird. So the second slide, the slide we would be looking at is the Yuba watershed, just so we know where we live. Three-fourths of the Yuba, everybody knows you move eastward, you move upslope. Yuba is a tributary of the feather, which flows to the Sacramento, which flows into San Francisco Bay. Now, the next one was going to be a language map. Yeah, I could prompt myself. I get comedic. [LAUGHTER] Well, that's all right. I have this too. OK, but I thought maybe if you got it up here, and at least people could appear. Oh, yeah. No? No. OK. The next was a language map. Lots of people are confused by-- they hear "my-you. " I think that's what the native people around here refer to themselves as earlier in the 20th century, because Nissinan is a little more exotic sounding. And there were so few families around that you couldn't really call yourself a separate group. So they bonded together with other my-you. But the people who lived here have always been known as Nissinan. And that's a pretty wide language group that extends from the Kasumnus River north to the North Yuba, just above the North Yuba. The next one was a GeoHuff map. The whole idea-- the Nissinan were hunters and gatherers. Can you hear me? The Nissinan were hunters and gatherers. A lot of people just think that involves a little bit of knowledge and then wandering around and knowing a couple of good places to hunt and gather. But it's far more sophisticated than that. In addition to the practical side of it, this culture, for one thing, we have a hard time understanding them, because we keep looking for village sites and big village sites. And actually, a good part of their lives is spent in motion. And it's not like something undesirable for them to live fully in this area without agriculture as we know it. You would have to take advantage of at least two ecosystems and preferably three. So that involved moving around. On the practical side, you would move around for food. For instance, you'd go into the mountains in the winter and spend a week or so collecting sugar pine nuts. Then moving on to the next stop. That's one kind of food. There were all kinds of foods. And they kept moving around to take advantage of the ripening of the plant materials and the migrations of animals like deer and salmon and birds. The other thing that was practical about it was they collected materials for baskets. These are outstanding basket makers, world-renowned, first class. They took it very seriously to get-- I don't have the figures-- but to get enough rods together of equal size and equal taper to provide the uprights for a basket. That task alone might take two years or so to find them. Now, in addition to the food and taking advantage of plants ripening and animal migrations, this was a multidimensional thing, this moving around. One aspect of it obviously is trade. You come up against the territory of another group. The people from Colfax say you're over around Chicago Park. There's great communication between all these groups because there's always individuals, families, and groups of people moving around. So everybody was pretty up to date on the news. So if you were headed over towards Colfax, the Colfax people might say, hey, we just traded with the Washoe. We have some great things. Why don't we meet up in Chicago Park and we'll do some more trading? So trade is one aspect of it. Another is diplomacy. There are always issues to hire now. Another aspect of it is a ceremonial cycle. Often these ceremonial cycles are tied in with seasons, like harvest. There's a wonderful one that celebrates the coming of spring and the flowers. It's called Weda. And they would have immense gatherings, invite people that work for many different groups, wear as many flowers as you possibly can. This signals a fruitful season. And there were plenty of other ceremonies too. And another aspect is social-- song, dance, storytelling, finding mates. Most of these get-togethers had all these dimensions to them. And then the final one that I know of, and I'm sure there are more, is like an auspicious or sacred landscape. There are places that move each and every one of us. And these places may be obvious because of their beauty. And on the other hand, they may be pretty plain looking, but connected to a remembered story that ties in with the creation myth. And so they're important in that dimension. What the map I had had, like trails of the indigenous people, just to illustrate how much they did get around. An awful lot of them were on ridges because if you don't stay on ridge tops, if you drop down slow a little bit and you start moving upstream, you're going to be going in and out of drainages like this. And unless it's deliberate, it'll take a long time. And what it showed really clearly that you could refer to this area where we live and where the Nissi Nahn lived as ridge and canyon country. I think that's a good descriptor. And at these geohubs, these were training centers. There are places where the trails would come together. Nevada City was one. Another one would be the Empire Ranch down around Smartsville. Colfax was another. Auburn was another. And people would get together and train. There would always be some degree of trade because it's at a crossroads. These places also had good springs, plenty of resources on hand. And a point I'd like to make, they were also cosmopolitan. Like a city or a commercial and social center would be anywhere. Quite cosmopolitan, meaning that there would be people from far away, piyouts maybe passing through. Sometimes horse traders would come down from the Colombian plateau. You'd have people from all over. I mean, it's not like staying home in your small, isolated camp to go to one of these geohubs. It would be like going to town. I had a small map-- we had a small map-- that showed Nevada City. Nevada City is kind of unique. I talked about these unusual auspicious landscapes. The interesting thing about Nevada City, the main feature of Nevada City is, of course, Deer Creek. But then you have come into it right in town. You have Little Deer Creek. You have Golden Flat. And you have Manzanita Ravine, which is now under the freeway. But it forms kind of a mandala, the way they came together. And between each of these streams were ridges. And if you head out those ridges, say if you had an east out between Little Deer Creek and Deer Creek, you'd wind up-- you could take a split taking you up onto the Washington Ridge, which would take you all the way up to the Bear Valley and onto that ridge that becomes a Dutch flat divide, takes you up to the summit and deal with the Washoe. You could also, to the east, head a little to the south and go up to the headwaters of the Bear River, Quaker Hill, et cetera, going in different directions. This would be so much easier with graphics. There was a picture of a woman called Kodo Jane, taken in 1874. And the caption underneath of it said, "Indian girl with ornaments. " Well, these ornaments she was wearing were big abalone-shelled discs, quite a few. And she also had ornaments of allobella shells and clamshell disc beads. All of these things are obviously from the coast, traded in from the coast. This was a person of nobility. And like even in medieval times for us, you made yourself distinctive from the masses, usually through jewelry, ornaments, your behavior, all of that. So there was that element to it. The next shot was one you may have seen many times. And it was in 1850 right here in Nevada City. We're switching to mining now. And it shows a whole hillside. It's a pencil drawing from a photograph of coyote holes. The first-- all of the gold in the early part of the gold rush was found on the stream side. So obviously, that's where they found it here in Nevada City as well. It was free gold. And nobody had taken it before. So it was there. Then they discovered by burrowing into the banks, there was more gold. So what they wound up doing was sinking holes big enough for you to go down into. I forget how the size of the claims at the time. But the whole hillside is just peppered with these. What they would do-- because gold is heavier than anything else it's associated with, much heavier. So it works its way to the bottom of any stream. And even a now dead stream, a stream that used to be the bottom, but now it's part of the bank over the eons. The creek may have moved a bit. The gold would be at the bottom of that too. They hadn't quite put it together. But they found that if they got down to bedrock through the gravel and then what they called drifting, move over to the side, they found plenty of gold. But it was an ecological mess. Getting the high sign to move on, I could stand here and blather all night. But I want to make an important point. And that is we've heard this term shock and awe. It was used in a military sense. But I think that's exactly what the Nissi non-experienced when the miners showed up. Everything they needed was in the local environment. These guys come in for some-- in pursuit of something pretty abstract, gold. Really doesn't have any uses. And created an unbelievably barren landscape by taking down the trees, all the vegetation, all the soil even, then all the gravel. You're left with barren bedrock when they're finished. Now gold miners, when they came here, saw this as the frontier, something on the edge. At the same time, the Nissi non-called it their homeland. And Nevada City was their center. So you have these two points of view in conflict right there. One more thing, miners were sojourners. That means they were just visiting. They had no intention of settling here. It kind of calls me when people call the people in the Gold Rush settlers because they had no intention to settle here. In contrast, the Nissi non-means of this place, they're totally embedded in this place. They had always lived here. So I'm getting the high sign to move on. I have plenty more. Sorry about this, folks. Yeah. We've done this many times. I cannot do this without the visuals. And I think some of you can see this if I brought this up here. We have a little bit of length here. OK. How about that? It turns around. I think it's-- OK. I think we can see it. It's not big. But-- No. But I think-- OK. Everybody want to move their chairs or-- [INTERPOSING VOICES] Whatever. All right. Better? Better. Worse. All right. All right. I want to talk tonight about Henry B. Brown. How many of you have ever heard of Henry B. Brown before? All right. Well, this is a treat because I want to introduce you to an amazing artist who spent about half of his time during an 18-month period from May 1851 to October 1852. And he spent a good time-- part of that time in Nevada County. And his artistic production reflects pictures of Indians, landscapes, and mining camps. And most people have never seen this. But the story is this is a book that was done on Henry B. Brown in 2006. And Henry B. Brown had been lost. His work had been lost and only recently rediscovered in the late 20th century. And today, you will see Henry Brown pictures in many places. But often, they don't have the names on them. He has name on it. They're just not attributed, right? So what he's famous for is ethnography. If you can see this image, it is a Kancow village in 1851. So he did things in an ethnographically correct way. So this is-- there's a lot of detail here showing an Indian village in a healthy state, intact, because he happened to be here at a window of time before native California population collapsed, which it did very rapidly in the early 1850s because of starvation and, as Hank has said, because of the mining that had destroyed so much habitat. So this, again, this is probably one of the most famous Henry Browns. And you may have seen this somewhere. And it's the interior of a Kancow lodge in the Sacramento Valley in 1852, showing a happy family in a very large, comfortable-looking structure. We know that here in Nisanon country, people have winter homes that extended families. So they were here, too. We have no ethnographic pictures of these. No artists did them. This is our one example for this whole northern California region of an interior of a lodge. Another very famous Henry Brown is an interior of a council house. Again, the only existing, earliest example of a interior of a council house. A kung, as it was called, is a dance house. And it's very similar material culture from the Sacramento Valley and through the foothills. People have these dance houses. And they were the central places for people. Now, these are very, very famous. So Henry B. Brown is very important because of the rarity of these images. And his ethnographic accuracy. But a third reason is that he treated his subjects synthetically. Most people caricatured Indian people and showed them as ugly and animalistic. But these are-- they show the humanity and the beauty of the people. How he got people to trust him so that he could get close and do these portraits is not really clear. Now, this picture shows the travels of Henry B. Brown in that 18-month period. He was stationed in San Francisco. So he spent the winters there. But in 1851, he met a man named John Russell Bartlett. And John Russell Bartlett was the head of the US Mexican Boundary Commission. And Bartlett hired Brown to go where he couldn't. So this long line here shows Henry B. Brown going from Sacramento all the way up to Mount Shasta. And that's when he did some of his most beautiful and most famous work during that 1852 trip. Because then he turned over those sketches to Bartlett. And then they vanished for 150 years. But what hasn't been discovered, what I discovered over the course of the last 18 months, is that Henry B. Brown spent a lot of time in Nevada County and did a lot of pictures here. This shows he didn't leave many letters to say where he'd gone. But he left a map. That was an 1850 map that anybody going into the old, cold region would have. And he marked it with a pencil. So we know which routes he went. And he went first to Coloma to see Sutter's Mill. Then he went north to the intersection of the immigrant trail and the route north, which was Storm's Ranch, also Chicago Park today. And this man named Simone Pena-Storms was very famous. And he ran a big hotel there. And it's in the Nevada County archives. Many stories about Simone Pena-Storms. Then he went to Grass Valley. Then he went to the Nevada City. And then he went to a place near Smart Spill called Empire Ranch. Have you heard of that? Or also called Mooney Flats, that area near Smart Spill. It's right on that ecotone right before you drop. You can get this beautiful view. So what I did is I had first learned-- here's a couple examples of Henry Brown's drawings. Here's a woman with a-- what do you call that? The mortar? Hopper mortar. She's got a basket. And she's pounding things. Here is a picture that has only recently come to light. And I wish you could see it. It's in the reprint. But this is the most touching and sweet picture. And so it's a little baby reaching for the sky with his little hand. And it just has such a delicacy. Now what I learned in the course of doing my research is that what Tom Blackburn had done is he published 33 of Henry B. Brown's best images. His best ones, somehow miraculously, 150 of them survived, 130. How old did my course? 130 survived. Unfortunately, many of those drawings were done in pencil. So they have become illegible. So this is an example. Using digitalization, what he looked like, just a blank piece of paper, when I looked at it in the archives in the Bancroft Library, then something comes to light. And you see a picture of a woman, and she's got a baby carrier. And this is a lovely, delicate picture of a man bending a net. Again, very damaged by time, but able to be used digitalization to improve it. Here, this is Henry Brown's map, which you can't see very well with the pencil lines on it. All right. So I first discovered Henry Brown because I was interested in a man named Chief Wima. And I knew about Chief Wima because our local historian, David Comstock, who many of you know, had done lots and lots of research on Wima. And Wima had done a book called the Gold Diggers in-- what was it called? I have it. The Gold Diggers in Camp Follow. That's the Gold Diggers in Camp Follow. And he had fictionalized Wima. Now Wima was the most pivotal diplomatic figure in Nissanam politics between 1848 and 1854. Wima signed the Treaty of Bear River. He signed the Treaty of Camp Union. And he also did another diplomatic talk in 1854 at Chicago Park at Storm's Ranch. He was the major negotiator for the Indian people. And he was called a king because he had so much regional power. So he's really, really important. Well, I found a picture of Wima in Brown's work. And so I was delighted. Because David Comstock had done so much research on Wima, Tom Black, who the author of the book, knew enough that he could identify him. But a few months ago, I started flipping through this book, looking for other things. And something struck me. And that was one third of the 33 best Brown drawings were done in Nevada County. One third, or neighboring Yuba County. So I went back to the drawing board. I went to the four archives where these images are and looked for everything on Nevada County. And I found some surprises that I wanted to show you tonight. And I hope you can see some of it, because this is stuff you've never, ever seen before. So as I said, they needed work because they had been digitized. They had to be digitized because they looked just like blank pieces of paper when I originally looked at them in the archives. Then I put together the clues that I had. And I put together a conjectural route for Henry B. Brown to have traveled in 1851, in the late fall of 1851. So as I said, he first went to Coloma. He wanted to make money in the gold rush. He wasn't a very strong person. We don't know much about him, but we think he was in the poor hell. He wasn't about to do any mining. But he thought he could make a living by creating a historic illustrated book, and then go back east and sell that. Because the people back east could not get enough of what was going on in California. So he first went to Coloma, did some sketches there, then bumpity bump, down and up and down and up, all those river valleys, the north branch of the American and so forth. And he finally got to the Bear River, right across the Bear River, where the immigrant trail in inner sex with the stage room was Storms Ranch. And this is a picture of Simone Panea Storms. We have a number of images. His buckskins are at the Catholic Church in Grass Valley. But this is the finest picture, and it's dated 1851. So I'm guessing it was done right there at Storms Ranch. And he's only 21 years old. And he was married to Weela's daughter. It was one of those political alliances. Storms was trading with the Indians. They were collecting gold. And he was selling them handkerchiefs and beef and raisins and making a fortune for himself. But he also had that hotel and a place for visitors and good food for its time. And of course, Brown would have stayed there with his cousin. This is one of Brown's most beautiful pictures. And that is of a chief called Bakla. And the chief named Bakla was a chief of a village in Chicago Park called Tui, or which translates to sleep. And he here is-- and he was the father of one of the descendants, Jane Crowde, who talked to anthropologist Little John in the 1820s. But what you can see here, abalone necklace, great wealth, clamshell, bees around his neck, a beautiful net hair thing. And he was royalty. He was royalty. These are called the hooks. And I think they were hereditary and that they were interconnected by marriage. So there were kind of ruling families. Now look, here is this guy. And we think he's from Chicago Park. Here's a man who is from Chico. We have only one picture of the treaty negotiations that went on in 1851, '52. But in this surviving photograph, and these men look almost identical, so that you would think that maybe they are the same person. My theory is they're first cousins, that these were interlocking families of the elite. All right, Brown and Grass Valley. So after he's in storms, he gets north to Grass Valley. And what does he find there? He finds grass. The name Grass Valley, anybody know where that came from? It was attributed to some French soldiers who were passed up the Donner Party in the fall of 1846, where the Donner Party were unfortunately held back. But the Frenchman got to the Greenhorn, and they were resting there. And their cattle wandered away and found grass in a valley. And that's how Grass Valley got its name. Well, this is a picture of Grass Valley in 1851, '52. This is a picture of Wolf Creek. Never been published before. And once I digitized it, you can see a lot more detail. He spent a lot of time working on this. And anybody who had a lot of skill probably could do a better job than I did. But it's a wonderful picture of Wolf Creek. Then he went to Gold Hill. Anybody know what Gold Hill was? All right? Pat? All right, 1850, the first court's mind. He did three or four pictures of Gold Hill. He's doing an illustrated history. So of course, he would find that to be historically significant. And then this is called Entrance to a Court's Mind. And it's very, very early, 1851, '52. So these are some of the earliest drawings. Then after he was in Grass Valley, he moved on to Nevada City. And this is the big climax of the talk, because none of these pictures have ever been published before or shown before to anyone. He did at least seven pictures in Nevada City, all of them landscapes. All right? I guess this would make eight. This one is in our book and has been published in Nevada City Beesonon. And it is a mine. The title is "Courtes Mill, Near Nevada City. " So it is the very first picture of a mill, a stamp mill. And what you can see, it's using gravity to process things. There's sluices there at the bottom. You can't see it very well, but it is in the book if you want to check it out. All right, here's one of his landscapes. And this is looking from Sugarloaf across. And you can see Banner Mountain in the distance. Then he has these black blotches, which represent Deer Creek. But I think it means something else, like tailings, because he does this in other drawings, these little black blotches. And so that's kind of pretty. Here are another one. These are called Near Nevada City, no dates on them. This one, again, looking towards Banner Mountain from Sugarloaf. And you can see the Deer Creek, that dark area there. Here's one that was before it was digitized. Looks like nothing. You can't see anything. Once you enlarge it and digitize it, people, houses, horses, minds, sluices, all kinds of things start to appear. This is a wonderful and rare picture of Nevada City in 1851. Again, before digitalization and then after. And different things, features, mining features, miners' cabins, sluices and things start to appear. Interesting thing here is just details. I can show you afterwards if anybody wants to come up and look at the details. Interesting thing here, I cropped a part of it and enlarged it. And the people had all moved their houses onto the ledge so they could be on a flat area rather than on the hillside there. Here's one. This is called Meadow Near Nevada City. Once it's digitized, you can see a cow and a meadow. Not much more. This is one of my favorites. Very faintly, you can see these round shapes. And I thought, oh my gosh, I have finally done it. I found the one and only picture of Nevada City Indian people with domed houses. They're winter houses. I have no one else has ever found a picture of this. I thought I was going to be written up in anthropological history. I found something no one had seen before, a winter village of the Nisenon. I digitalized it. And some more details. You can see those rounded huts there. And then before I sent this off to get my prize money, I discovered loose stones. It wasn't a village. It was, in fact, a deconstructed landscape of broken and fallen trees and stones being uprooted because of all the water washing through that. It was a mining site. Brown on the Yuba River. Now, we know he was down at the Yuba River because he did some absolutely beautiful work there. And this is at that place called Empire Ranch, which is right next to Union Ranch, which is right on the hillside above the Yuba River, above Rose's Bar. Anybody know where Rose's Bar is or in Smartsville? Right in that area, right where you cross the river on Highway 20, right? So it's the bluff there. Now, we know he was there. One reason is that there was a wagon road. This picture shows George Horatio Derby, who was with the original topographic engineers who was doing explorations. And it shows that in Sutter's era, he had built a wagon road from Sacramento to Rose's Bar there on the Yuba River to Cardulla's Ranch. And so we know there was this very flat, accessible road. And of course, there was a tremendous amount of gold there. And our friend David Lawler can tell us how much gold there was. But there were big camps. There were hotels. There were eateries. And there were over 1,000 Indians. And how of 2,000, 3,000, 4,000, 5,000 miners there in 1851, '52, because it was tremendously rich. And the Indians, of course, are mining themselves, either in labor proofs or for themselves, and buying food with the gold that they collect. All right, this is a picture of Rose's Bar on the Yuba River by Henry B. Brown, 1851. And it's an absolutely beautiful picture. I can't see it very well. He also did Marysville Buttes, which the Nisanon call Esto Theomani. And that is-- you can see the little buttes in the background. Again, you're from a raised position on the block, looking down westward over the valley. Another picture, Industry Bar, which is now under angle break. All right, but it was one of the mining. And it has a lot of detail about the miners there. He also did pictures of Indians on the Yuba River, because he said, Indian young girls grinding acorns at the Yuba River. They called it Ooba, Uber River. All right, and this is very endearing, never been published before. Pictures of girls, and the girl is smiling, and they're pounding the acorns. This one is men gambling on the Ouba River. And it shows them engrossed in a gambling game. And notice this guy, this guy with a bandana wrapped around his head. Well, what I discovered was that many of Brown's portraits were individual studies of the men who are gambling here. So we know those portraits were done on the Yuba River as well. And this is the most gorgeous, most beautiful, most exquisite ethnographic drawing. And it is of a morning ceremony on the Yuba River. It's specifically titled that Yuba River morning ceremony. And what you see is the details of-- they have these tall poles, and they would put offerings on them, and then give those to the fire as a sacrifice. The women would take the ashes of the dead, smear it with pitch, and put it on their bodies as a sign of grief. And in the back-- so you can see the women dabbing this on their other women's faces. And then in the back, you can see people singing. I mean, it's absolutely a beautiful artistically and ethnographically, and there's nothing like it to compare. This is one we digitized. And it's really interesting. It's called Indian Old Women Brining Acorns. But what you see in this one, you see she has kind of a helmet-like-- it wasn't just dabbing pieces, you know, the soot and ash and pitch. There was a style. And it shows that there was-- it went neatly underneath the cheek bone here. And the idea was, when you cried, it would make the maximum amount of mass of all the tears and the blackness. And this is a very, very rare image to have something, a recording of that. There's Weema. Weema is an interesting guy because you don't see him wearing any jewelry, the traditional signs of authority and royalty. He has a white man's shirt on, and he's shown with a young girl or boy who does have the abalone necklace on and lots and lots of beads. And for many of these browns, I've discovered there's duplicate coffees. And so this one is a little bit different. Shows the boy or girl in a different position and Weema with a little more handsome, I think. We have pictures. This is 1855. Storms and Weema. Weema was given a military coat at the time of the Camp Union Treaty in 1851. And he wore it all the time. And here is his picture in his military coat with standing next to some non-pena storms who became an Indian agent at Round Valley. And Weema and others were deported there in the Indian Removal Period. Now, we have three pictures of signers of the 1851 Treaty of Camp Union. And that was very important. I don't know if you've ever heard about the 18 unratified treaties in California. But what happened was that it was federal precedent that you could not have legal title to land unless the federal government had gone in and purchased the occupancy rights from the Indians. So here, all these gold miners had rushed in for the federal government and had time to negotiate treaties. So technically, the land still belonged to the Indians, according to federal Indian law. So 1851, a little bit too late, the Federal Treaty Commissioners come in. And California at that time had a strong political contingent who were Southerners and Democrats who believed in slavery and didn't believe Indians should have any rights either. And that was unfortunate. Well, the treaty that was made at Camp Union, I think, was quite exceptional because there was a lot on the line because there was so much gold here. And Wazencraft, the treaty commissioner comes in in a position of weakness. And you can read all about that, of what transpired. But the fact that we have now the pictures of the men who signed the treaty and the other details tells us a lot more of what happened there. This is Tocola. And there's two visions and versions of it. And Tocola, maybe you've heard in Nevada County, Colley, Coley, there's a number of chiefs who had that similar name. Again, I think it's evidence that there was royal families with names. And look at this guy's face. You can't see it very well. This was a picture done by a Frenchman. And he looks exactly the same. It's either the same man or it's a cousin. So in the third person who signed the treaty was Walupa. And that's who the town of Walupa was named. And he also, he was believed to be a Mission Indian. And like Lima, he was very worldly wise. He was multilingual. He probably had a horse to get around a lot. And we know these were done at the site of Camp Union, because you can see the Sierra Buttes in the background, in both the Tocola and in Walupa's image. And Walupa is very well known in the Nevada County Archives because of a bulletin article that was published. And it tells of an event in 1853 when Chief Walupa appealed to a grass valley shopkeeper for credit. He said, "At present we have no gold, but when the rains of spring shall have washed the hillsides and the resines of which my people knew we will have gold in abundance. " And the shopkeeper trusted him, gave him some bags of flour and other food. And the following spring, 40 men brought sacks of 100 to 150 weight in gold to the shopkeeper. So he was paid back many times over. All right. This is the final slide. And then I'll let you go. Again, one that had never been published before. But it's a picture. It's a dramatic picture because it shows some kind of fight going on. A man here, a white man in a hat. There's a small child behind him that he seems to be protecting. This Indian man is advancing. Was this child stolen? Was the Indian trying to get him back? It's hard to tell what's going on. This man is trying to mediate. But there's a woman in the foreground who has a Plains Indian braids. So this is fascinating. It tells how many Indians of different tribes showed up in Nevada County during the gold rush, not just local people, but Walla Wallas and Cherokees and people from all over came in. So it's an interesting image. At the end, damn. [APPLAUSE]

So that's pretty philosophically weird. So the second slide, the slide we would be looking at is the Yuba watershed, just so we know where we live. Three-fourths of the Yuba, everybody knows you move eastward, you move upslope. Yuba is a tributary of the feather, which flows to the Sacramento, which flows into San Francisco Bay. Now, the next one was going to be a language map. Yeah, I could prompt myself. I get comedic. [LAUGHTER] Well, that's all right. I have this too. OK, but I thought maybe if you got it up here, and at least people could appear. Oh, yeah. No? No. OK. The next was a language map. Lots of people are confused by-- they hear "my-you. " I think that's what the native people around here refer to themselves as earlier in the 20th century, because Nissinan is a little more exotic sounding. And there were so few families around that you couldn't really call yourself a separate group. So they bonded together with other my-you. But the people who lived here have always been known as Nissinan. And that's a pretty wide language group that extends from the Kasumnus River north to the North Yuba, just above the North Yuba. The next one was a GeoHuff map. The whole idea-- the Nissinan were hunters and gatherers. Can you hear me? The Nissinan were hunters and gatherers. A lot of people just think that involves a little bit of knowledge and then wandering around and knowing a couple of good places to hunt and gather. But it's far more sophisticated than that. In addition to the practical side of it, this culture, for one thing, we have a hard time understanding them, because we keep looking for village sites and big village sites. And actually, a good part of their lives is spent in motion. And it's not like something undesirable for them to live fully in this area without agriculture as we know it. You would have to take advantage of at least two ecosystems and preferably three. So that involved moving around. On the practical side, you would move around for food. For instance, you'd go into the mountains in the winter and spend a week or so collecting sugar pine nuts. Then moving on to the next stop. That's one kind of food. There were all kinds of foods. And they kept moving around to take advantage of the ripening of the plant materials and the migrations of animals like deer and salmon and birds. The other thing that was practical about it was they collected materials for baskets. These are outstanding basket makers, world-renowned, first class. They took it very seriously to get-- I don't have the figures-- but to get enough rods together of equal size and equal taper to provide the uprights for a basket. That task alone might take two years or so to find them. Now, in addition to the food and taking advantage of plants ripening and animal migrations, this was a multidimensional thing, this moving around. One aspect of it obviously is trade. You come up against the territory of another group. The people from Colfax say you're over around Chicago Park. There's great communication between all these groups because there's always individuals, families, and groups of people moving around. So everybody was pretty up to date on the news. So if you were headed over towards Colfax, the Colfax people might say, hey, we just traded with the Washoe. We have some great things. Why don't we meet up in Chicago Park and we'll do some more trading? So trade is one aspect of it. Another is diplomacy. There are always issues to hire now. Another aspect of it is a ceremonial cycle. Often these ceremonial cycles are tied in with seasons, like harvest. There's a wonderful one that celebrates the coming of spring and the flowers. It's called Weda. And they would have immense gatherings, invite people that work for many different groups, wear as many flowers as you possibly can. This signals a fruitful season. And there were plenty of other ceremonies too. And another aspect is social-- song, dance, storytelling, finding mates. Most of these get-togethers had all these dimensions to them. And then the final one that I know of, and I'm sure there are more, is like an auspicious or sacred landscape. There are places that move each and every one of us. And these places may be obvious because of their beauty. And on the other hand, they may be pretty plain looking, but connected to a remembered story that ties in with the creation myth. And so they're important in that dimension. What the map I had had, like trails of the indigenous people, just to illustrate how much they did get around. An awful lot of them were on ridges because if you don't stay on ridge tops, if you drop down slow a little bit and you start moving upstream, you're going to be going in and out of drainages like this. And unless it's deliberate, it'll take a long time. And what it showed really clearly that you could refer to this area where we live and where the Nissi Nahn lived as ridge and canyon country. I think that's a good descriptor. And at these geohubs, these were training centers. There are places where the trails would come together. Nevada City was one. Another one would be the Empire Ranch down around Smartsville. Colfax was another. Auburn was another. And people would get together and train. There would always be some degree of trade because it's at a crossroads. These places also had good springs, plenty of resources on hand. And a point I'd like to make, they were also cosmopolitan. Like a city or a commercial and social center would be anywhere. Quite cosmopolitan, meaning that there would be people from far away, piyouts maybe passing through. Sometimes horse traders would come down from the Colombian plateau. You'd have people from all over. I mean, it's not like staying home in your small, isolated camp to go to one of these geohubs. It would be like going to town. I had a small map-- we had a small map-- that showed Nevada City. Nevada City is kind of unique. I talked about these unusual auspicious landscapes. The interesting thing about Nevada City, the main feature of Nevada City is, of course, Deer Creek. But then you have come into it right in town. You have Little Deer Creek. You have Golden Flat. And you have Manzanita Ravine, which is now under the freeway. But it forms kind of a mandala, the way they came together. And between each of these streams were ridges. And if you head out those ridges, say if you had an east out between Little Deer Creek and Deer Creek, you'd wind up-- you could take a split taking you up onto the Washington Ridge, which would take you all the way up to the Bear Valley and onto that ridge that becomes a Dutch flat divide, takes you up to the summit and deal with the Washoe. You could also, to the east, head a little to the south and go up to the headwaters of the Bear River, Quaker Hill, et cetera, going in different directions. This would be so much easier with graphics. There was a picture of a woman called Kodo Jane, taken in 1874. And the caption underneath of it said, "Indian girl with ornaments. " Well, these ornaments she was wearing were big abalone-shelled discs, quite a few. And she also had ornaments of allobella shells and clamshell disc beads. All of these things are obviously from the coast, traded in from the coast. This was a person of nobility. And like even in medieval times for us, you made yourself distinctive from the masses, usually through jewelry, ornaments, your behavior, all of that. So there was that element to it. The next shot was one you may have seen many times. And it was in 1850 right here in Nevada City. We're switching to mining now. And it shows a whole hillside. It's a pencil drawing from a photograph of coyote holes. The first-- all of the gold in the early part of the gold rush was found on the stream side. So obviously, that's where they found it here in Nevada City as well. It was free gold. And nobody had taken it before. So it was there. Then they discovered by burrowing into the banks, there was more gold. So what they wound up doing was sinking holes big enough for you to go down into. I forget how the size of the claims at the time. But the whole hillside is just peppered with these. What they would do-- because gold is heavier than anything else it's associated with, much heavier. So it works its way to the bottom of any stream. And even a now dead stream, a stream that used to be the bottom, but now it's part of the bank over the eons. The creek may have moved a bit. The gold would be at the bottom of that too. They hadn't quite put it together. But they found that if they got down to bedrock through the gravel and then what they called drifting, move over to the side, they found plenty of gold. But it was an ecological mess. Getting the high sign to move on, I could stand here and blather all night. But I want to make an important point. And that is we've heard this term shock and awe. It was used in a military sense. But I think that's exactly what the Nissi non-experienced when the miners showed up. Everything they needed was in the local environment. These guys come in for some-- in pursuit of something pretty abstract, gold. Really doesn't have any uses. And created an unbelievably barren landscape by taking down the trees, all the vegetation, all the soil even, then all the gravel. You're left with barren bedrock when they're finished. Now gold miners, when they came here, saw this as the frontier, something on the edge. At the same time, the Nissi non-called it their homeland. And Nevada City was their center. So you have these two points of view in conflict right there. One more thing, miners were sojourners. That means they were just visiting. They had no intention of settling here. It kind of calls me when people call the people in the Gold Rush settlers because they had no intention to settle here. In contrast, the Nissi non-means of this place, they're totally embedded in this place. They had always lived here. So I'm getting the high sign to move on. I have plenty more. Sorry about this, folks. Yeah. We've done this many times. I cannot do this without the visuals. And I think some of you can see this if I brought this up here. We have a little bit of length here. OK. How about that? It turns around. I think it's-- OK. I think we can see it. It's not big. But-- No. But I think-- OK. Everybody want to move their chairs or-- [INTERPOSING VOICES] Whatever. All right. Better? Better. Worse. All right. All right. I want to talk tonight about Henry B. Brown. How many of you have ever heard of Henry B. Brown before? All right. Well, this is a treat because I want to introduce you to an amazing artist who spent about half of his time during an 18-month period from May 1851 to October 1852. And he spent a good time-- part of that time in Nevada County. And his artistic production reflects pictures of Indians, landscapes, and mining camps. And most people have never seen this. But the story is this is a book that was done on Henry B. Brown in 2006. And Henry B. Brown had been lost. His work had been lost and only recently rediscovered in the late 20th century. And today, you will see Henry Brown pictures in many places. But often, they don't have the names on them. He has name on it. They're just not attributed, right? So what he's famous for is ethnography. If you can see this image, it is a Kancow village in 1851. So he did things in an ethnographically correct way. So this is-- there's a lot of detail here showing an Indian village in a healthy state, intact, because he happened to be here at a window of time before native California population collapsed, which it did very rapidly in the early 1850s because of starvation and, as Hank has said, because of the mining that had destroyed so much habitat. So this, again, this is probably one of the most famous Henry Browns. And you may have seen this somewhere. And it's the interior of a Kancow lodge in the Sacramento Valley in 1852, showing a happy family in a very large, comfortable-looking structure. We know that here in Nisanon country, people have winter homes that extended families. So they were here, too. We have no ethnographic pictures of these. No artists did them. This is our one example for this whole northern California region of an interior of a lodge. Another very famous Henry Brown is an interior of a council house. Again, the only existing, earliest example of a interior of a council house. A kung, as it was called, is a dance house. And it's very similar material culture from the Sacramento Valley and through the foothills. People have these dance houses. And they were the central places for people. Now, these are very, very famous. So Henry B. Brown is very important because of the rarity of these images. And his ethnographic accuracy. But a third reason is that he treated his subjects synthetically. Most people caricatured Indian people and showed them as ugly and animalistic. But these are-- they show the humanity and the beauty of the people. How he got people to trust him so that he could get close and do these portraits is not really clear. Now, this picture shows the travels of Henry B. Brown in that 18-month period. He was stationed in San Francisco. So he spent the winters there. But in 1851, he met a man named John Russell Bartlett. And John Russell Bartlett was the head of the US Mexican Boundary Commission. And Bartlett hired Brown to go where he couldn't. So this long line here shows Henry B. Brown going from Sacramento all the way up to Mount Shasta. And that's when he did some of his most beautiful and most famous work during that 1852 trip. Because then he turned over those sketches to Bartlett. And then they vanished for 150 years. But what hasn't been discovered, what I discovered over the course of the last 18 months, is that Henry B. Brown spent a lot of time in Nevada County and did a lot of pictures here. This shows he didn't leave many letters to say where he'd gone. But he left a map. That was an 1850 map that anybody going into the old, cold region would have. And he marked it with a pencil. So we know which routes he went. And he went first to Coloma to see Sutter's Mill. Then he went north to the intersection of the immigrant trail and the route north, which was Storm's Ranch, also Chicago Park today. And this man named Simone Pena-Storms was very famous. And he ran a big hotel there. And it's in the Nevada County archives. Many stories about Simone Pena-Storms. Then he went to Grass Valley. Then he went to the Nevada City. And then he went to a place near Smart Spill called Empire Ranch. Have you heard of that? Or also called Mooney Flats, that area near Smart Spill. It's right on that ecotone right before you drop. You can get this beautiful view. So what I did is I had first learned-- here's a couple examples of Henry Brown's drawings. Here's a woman with a-- what do you call that? The mortar? Hopper mortar. She's got a basket. And she's pounding things. Here is a picture that has only recently come to light. And I wish you could see it. It's in the reprint. But this is the most touching and sweet picture. And so it's a little baby reaching for the sky with his little hand. And it just has such a delicacy. Now what I learned in the course of doing my research is that what Tom Blackburn had done is he published 33 of Henry B. Brown's best images. His best ones, somehow miraculously, 150 of them survived, 130. How old did my course? 130 survived. Unfortunately, many of those drawings were done in pencil. So they have become illegible. So this is an example. Using digitalization, what he looked like, just a blank piece of paper, when I looked at it in the archives in the Bancroft Library, then something comes to light. And you see a picture of a woman, and she's got a baby carrier. And this is a lovely, delicate picture of a man bending a net. Again, very damaged by time, but able to be used digitalization to improve it. Here, this is Henry Brown's map, which you can't see very well with the pencil lines on it. All right. So I first discovered Henry Brown because I was interested in a man named Chief Wima. And I knew about Chief Wima because our local historian, David Comstock, who many of you know, had done lots and lots of research on Wima. And Wima had done a book called the Gold Diggers in-- what was it called? I have it. The Gold Diggers in Camp Follow. That's the Gold Diggers in Camp Follow. And he had fictionalized Wima. Now Wima was the most pivotal diplomatic figure in Nissanam politics between 1848 and 1854. Wima signed the Treaty of Bear River. He signed the Treaty of Camp Union. And he also did another diplomatic talk in 1854 at Chicago Park at Storm's Ranch. He was the major negotiator for the Indian people. And he was called a king because he had so much regional power. So he's really, really important. Well, I found a picture of Wima in Brown's work. And so I was delighted. Because David Comstock had done so much research on Wima, Tom Black, who the author of the book, knew enough that he could identify him. But a few months ago, I started flipping through this book, looking for other things. And something struck me. And that was one third of the 33 best Brown drawings were done in Nevada County. One third, or neighboring Yuba County. So I went back to the drawing board. I went to the four archives where these images are and looked for everything on Nevada County. And I found some surprises that I wanted to show you tonight. And I hope you can see some of it, because this is stuff you've never, ever seen before. So as I said, they needed work because they had been digitized. They had to be digitized because they looked just like blank pieces of paper when I originally looked at them in the archives. Then I put together the clues that I had. And I put together a conjectural route for Henry B. Brown to have traveled in 1851, in the late fall of 1851. So as I said, he first went to Coloma. He wanted to make money in the gold rush. He wasn't a very strong person. We don't know much about him, but we think he was in the poor hell. He wasn't about to do any mining. But he thought he could make a living by creating a historic illustrated book, and then go back east and sell that. Because the people back east could not get enough of what was going on in California. So he first went to Coloma, did some sketches there, then bumpity bump, down and up and down and up, all those river valleys, the north branch of the American and so forth. And he finally got to the Bear River, right across the Bear River, where the immigrant trail in inner sex with the stage room was Storms Ranch. And this is a picture of Simone Panea Storms. We have a number of images. His buckskins are at the Catholic Church in Grass Valley. But this is the finest picture, and it's dated 1851. So I'm guessing it was done right there at Storms Ranch. And he's only 21 years old. And he was married to Weela's daughter. It was one of those political alliances. Storms was trading with the Indians. They were collecting gold. And he was selling them handkerchiefs and beef and raisins and making a fortune for himself. But he also had that hotel and a place for visitors and good food for its time. And of course, Brown would have stayed there with his cousin. This is one of Brown's most beautiful pictures. And that is of a chief called Bakla. And the chief named Bakla was a chief of a village in Chicago Park called Tui, or which translates to sleep. And he here is-- and he was the father of one of the descendants, Jane Crowde, who talked to anthropologist Little John in the 1820s. But what you can see here, abalone necklace, great wealth, clamshell, bees around his neck, a beautiful net hair thing. And he was royalty. He was royalty. These are called the hooks. And I think they were hereditary and that they were interconnected by marriage. So there were kind of ruling families. Now look, here is this guy. And we think he's from Chicago Park. Here's a man who is from Chico. We have only one picture of the treaty negotiations that went on in 1851, '52. But in this surviving photograph, and these men look almost identical, so that you would think that maybe they are the same person. My theory is they're first cousins, that these were interlocking families of the elite. All right, Brown and Grass Valley. So after he's in storms, he gets north to Grass Valley. And what does he find there? He finds grass. The name Grass Valley, anybody know where that came from? It was attributed to some French soldiers who were passed up the Donner Party in the fall of 1846, where the Donner Party were unfortunately held back. But the Frenchman got to the Greenhorn, and they were resting there. And their cattle wandered away and found grass in a valley. And that's how Grass Valley got its name. Well, this is a picture of Grass Valley in 1851, '52. This is a picture of Wolf Creek. Never been published before. And once I digitized it, you can see a lot more detail. He spent a lot of time working on this. And anybody who had a lot of skill probably could do a better job than I did. But it's a wonderful picture of Wolf Creek. Then he went to Gold Hill. Anybody know what Gold Hill was? All right? Pat? All right, 1850, the first court's mind. He did three or four pictures of Gold Hill. He's doing an illustrated history. So of course, he would find that to be historically significant. And then this is called Entrance to a Court's Mind. And it's very, very early, 1851, '52. So these are some of the earliest drawings. Then after he was in Grass Valley, he moved on to Nevada City. And this is the big climax of the talk, because none of these pictures have ever been published before or shown before to anyone. He did at least seven pictures in Nevada City, all of them landscapes. All right? I guess this would make eight. This one is in our book and has been published in Nevada City Beesonon. And it is a mine. The title is "Courtes Mill, Near Nevada City. " So it is the very first picture of a mill, a stamp mill. And what you can see, it's using gravity to process things. There's sluices there at the bottom. You can't see it very well, but it is in the book if you want to check it out. All right, here's one of his landscapes. And this is looking from Sugarloaf across. And you can see Banner Mountain in the distance. Then he has these black blotches, which represent Deer Creek. But I think it means something else, like tailings, because he does this in other drawings, these little black blotches. And so that's kind of pretty. Here are another one. These are called Near Nevada City, no dates on them. This one, again, looking towards Banner Mountain from Sugarloaf. And you can see the Deer Creek, that dark area there. Here's one that was before it was digitized. Looks like nothing. You can't see anything. Once you enlarge it and digitize it, people, houses, horses, minds, sluices, all kinds of things start to appear. This is a wonderful and rare picture of Nevada City in 1851. Again, before digitalization and then after. And different things, features, mining features, miners' cabins, sluices and things start to appear. Interesting thing here is just details. I can show you afterwards if anybody wants to come up and look at the details. Interesting thing here, I cropped a part of it and enlarged it. And the people had all moved their houses onto the ledge so they could be on a flat area rather than on the hillside there. Here's one. This is called Meadow Near Nevada City. Once it's digitized, you can see a cow and a meadow. Not much more. This is one of my favorites. Very faintly, you can see these round shapes. And I thought, oh my gosh, I have finally done it. I found the one and only picture of Nevada City Indian people with domed houses. They're winter houses. I have no one else has ever found a picture of this. I thought I was going to be written up in anthropological history. I found something no one had seen before, a winter village of the Nisenon. I digitalized it. And some more details. You can see those rounded huts there. And then before I sent this off to get my prize money, I discovered loose stones. It wasn't a village. It was, in fact, a deconstructed landscape of broken and fallen trees and stones being uprooted because of all the water washing through that. It was a mining site. Brown on the Yuba River. Now, we know he was down at the Yuba River because he did some absolutely beautiful work there. And this is at that place called Empire Ranch, which is right next to Union Ranch, which is right on the hillside above the Yuba River, above Rose's Bar. Anybody know where Rose's Bar is or in Smartsville? Right in that area, right where you cross the river on Highway 20, right? So it's the bluff there. Now, we know he was there. One reason is that there was a wagon road. This picture shows George Horatio Derby, who was with the original topographic engineers who was doing explorations. And it shows that in Sutter's era, he had built a wagon road from Sacramento to Rose's Bar there on the Yuba River to Cardulla's Ranch. And so we know there was this very flat, accessible road. And of course, there was a tremendous amount of gold there. And our friend David Lawler can tell us how much gold there was. But there were big camps. There were hotels. There were eateries. And there were over 1,000 Indians. And how of 2,000, 3,000, 4,000, 5,000 miners there in 1851, '52, because it was tremendously rich. And the Indians, of course, are mining themselves, either in labor proofs or for themselves, and buying food with the gold that they collect. All right, this is a picture of Rose's Bar on the Yuba River by Henry B. Brown, 1851. And it's an absolutely beautiful picture. I can't see it very well. He also did Marysville Buttes, which the Nisanon call Esto Theomani. And that is-- you can see the little buttes in the background. Again, you're from a raised position on the block, looking down westward over the valley. Another picture, Industry Bar, which is now under angle break. All right, but it was one of the mining. And it has a lot of detail about the miners there. He also did pictures of Indians on the Yuba River, because he said, Indian young girls grinding acorns at the Yuba River. They called it Ooba, Uber River. All right, and this is very endearing, never been published before. Pictures of girls, and the girl is smiling, and they're pounding the acorns. This one is men gambling on the Ouba River. And it shows them engrossed in a gambling game. And notice this guy, this guy with a bandana wrapped around his head. Well, what I discovered was that many of Brown's portraits were individual studies of the men who are gambling here. So we know those portraits were done on the Yuba River as well. And this is the most gorgeous, most beautiful, most exquisite ethnographic drawing. And it is of a morning ceremony on the Yuba River. It's specifically titled that Yuba River morning ceremony. And what you see is the details of-- they have these tall poles, and they would put offerings on them, and then give those to the fire as a sacrifice. The women would take the ashes of the dead, smear it with pitch, and put it on their bodies as a sign of grief. And in the back-- so you can see the women dabbing this on their other women's faces. And then in the back, you can see people singing. I mean, it's absolutely a beautiful artistically and ethnographically, and there's nothing like it to compare. This is one we digitized. And it's really interesting. It's called Indian Old Women Brining Acorns. But what you see in this one, you see she has kind of a helmet-like-- it wasn't just dabbing pieces, you know, the soot and ash and pitch. There was a style. And it shows that there was-- it went neatly underneath the cheek bone here. And the idea was, when you cried, it would make the maximum amount of mass of all the tears and the blackness. And this is a very, very rare image to have something, a recording of that. There's Weema. Weema is an interesting guy because you don't see him wearing any jewelry, the traditional signs of authority and royalty. He has a white man's shirt on, and he's shown with a young girl or boy who does have the abalone necklace on and lots and lots of beads. And for many of these browns, I've discovered there's duplicate coffees. And so this one is a little bit different. Shows the boy or girl in a different position and Weema with a little more handsome, I think. We have pictures. This is 1855. Storms and Weema. Weema was given a military coat at the time of the Camp Union Treaty in 1851. And he wore it all the time. And here is his picture in his military coat with standing next to some non-pena storms who became an Indian agent at Round Valley. And Weema and others were deported there in the Indian Removal Period. Now, we have three pictures of signers of the 1851 Treaty of Camp Union. And that was very important. I don't know if you've ever heard about the 18 unratified treaties in California. But what happened was that it was federal precedent that you could not have legal title to land unless the federal government had gone in and purchased the occupancy rights from the Indians. So here, all these gold miners had rushed in for the federal government and had time to negotiate treaties. So technically, the land still belonged to the Indians, according to federal Indian law. So 1851, a little bit too late, the Federal Treaty Commissioners come in. And California at that time had a strong political contingent who were Southerners and Democrats who believed in slavery and didn't believe Indians should have any rights either. And that was unfortunate. Well, the treaty that was made at Camp Union, I think, was quite exceptional because there was a lot on the line because there was so much gold here. And Wazencraft, the treaty commissioner comes in in a position of weakness. And you can read all about that, of what transpired. But the fact that we have now the pictures of the men who signed the treaty and the other details tells us a lot more of what happened there. This is Tocola. And there's two visions and versions of it. And Tocola, maybe you've heard in Nevada County, Colley, Coley, there's a number of chiefs who had that similar name. Again, I think it's evidence that there was royal families with names. And look at this guy's face. You can't see it very well. This was a picture done by a Frenchman. And he looks exactly the same. It's either the same man or it's a cousin. So in the third person who signed the treaty was Walupa. And that's who the town of Walupa was named. And he also, he was believed to be a Mission Indian. And like Lima, he was very worldly wise. He was multilingual. He probably had a horse to get around a lot. And we know these were done at the site of Camp Union, because you can see the Sierra Buttes in the background, in both the Tocola and in Walupa's image. And Walupa is very well known in the Nevada County Archives because of a bulletin article that was published. And it tells of an event in 1853 when Chief Walupa appealed to a grass valley shopkeeper for credit. He said, "At present we have no gold, but when the rains of spring shall have washed the hillsides and the resines of which my people knew we will have gold in abundance. " And the shopkeeper trusted him, gave him some bags of flour and other food. And the following spring, 40 men brought sacks of 100 to 150 weight in gold to the shopkeeper. So he was paid back many times over. All right. This is the final slide. And then I'll let you go. Again, one that had never been published before. But it's a picture. It's a dramatic picture because it shows some kind of fight going on. A man here, a white man in a hat. There's a small child behind him that he seems to be protecting. This Indian man is advancing. Was this child stolen? Was the Indian trying to get him back? It's hard to tell what's going on. This man is trying to mediate. But there's a woman in the foreground who has a Plains Indian braids. So this is fascinating. It tells how many Indians of different tribes showed up in Nevada County during the gold rush, not just local people, but Walla Wallas and Cherokees and people from all over came in. So it's an interesting image. At the end, damn. [APPLAUSE]