Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

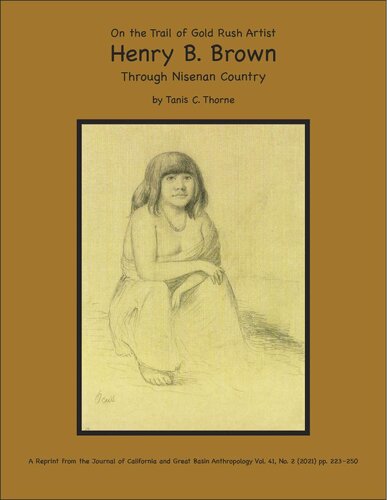

Video: 2024-01-18 - On the Trail of Gold Rush Artist Henry B. Brown in Nisenan Country with Tanis Thorne (59 minutes)

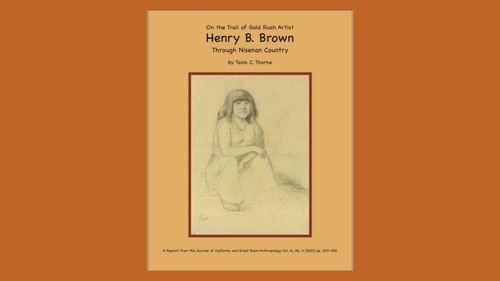

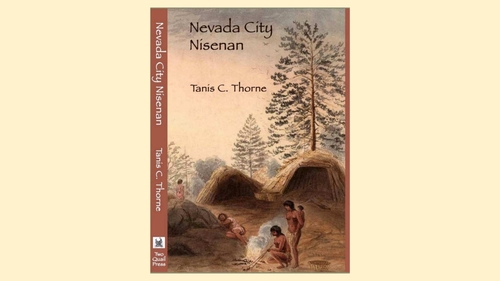

In the course of doing research on her 2022 book The Nevada City Nisenan, Tanis Thorne uncovered new information about gold rush artist Henry B. Brown. Though Brown's artistic renderings of landscapes and Native people have only recently come to light, his work is highly acclaimed for its ethnographic accuracy and artistic merit.

His portfolio includes drawings of landscapes, mining activity, and Native people, plus sketches and finished drawings done in Nevada City, Grass Valley, and the Empire Ranch/Union Ranch near present-day Smartsville. Thorne is excited to share Brown's drawings created during his repeated trips to Nevada County in 1851-1852 —some never seen or published before —and to tell the intriguing story of Brown and the excitement and foibles of doing research in archival collections.

This presentation is a reprise of the May 2022 Speaker Night presentation, where there were technical issues with the projector.

His portfolio includes drawings of landscapes, mining activity, and Native people, plus sketches and finished drawings done in Nevada City, Grass Valley, and the Empire Ranch/Union Ranch near present-day Smartsville. Thorne is excited to share Brown's drawings created during his repeated trips to Nevada County in 1851-1852 —some never seen or published before —and to tell the intriguing story of Brown and the excitement and foibles of doing research in archival collections.

This presentation is a reprise of the May 2022 Speaker Night presentation, where there were technical issues with the projector.

Author: Tanis Thorne

Published: 2024-01-18

Original Held At:

Published: 2024-01-18

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

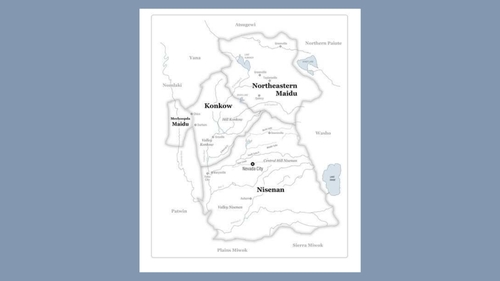

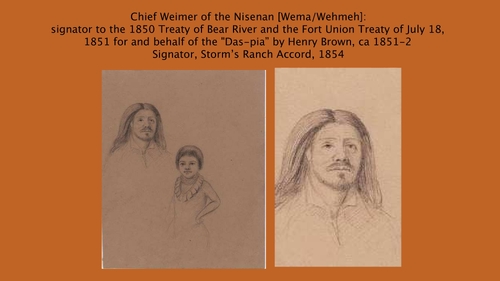

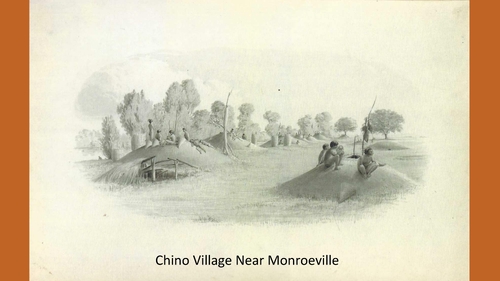

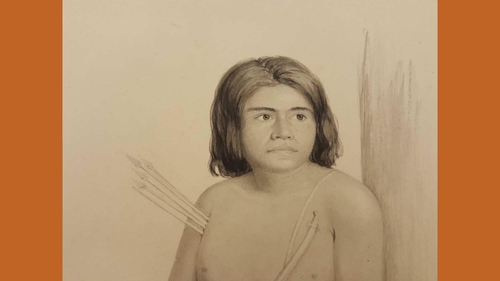

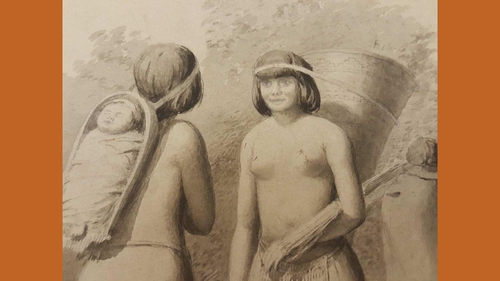

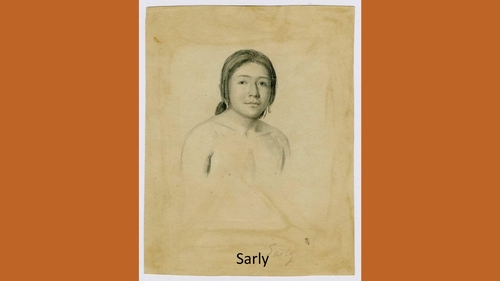

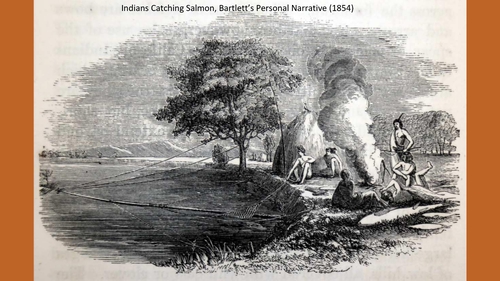

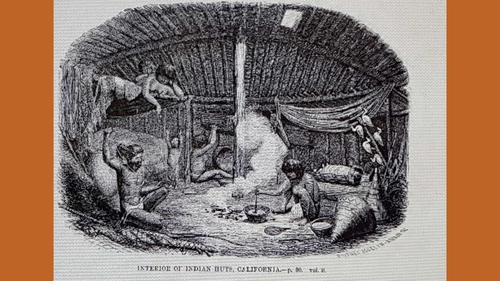

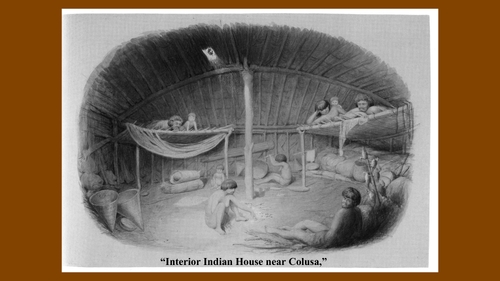

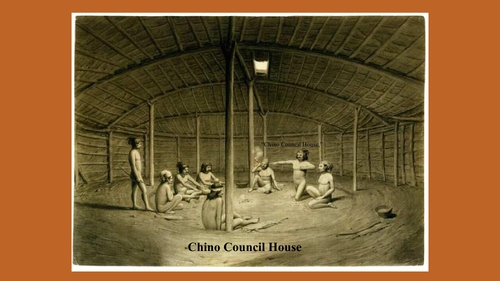

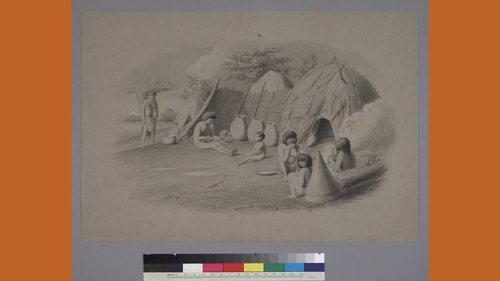

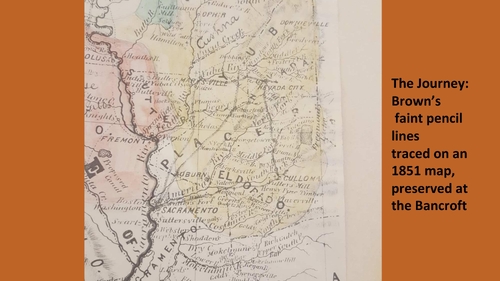

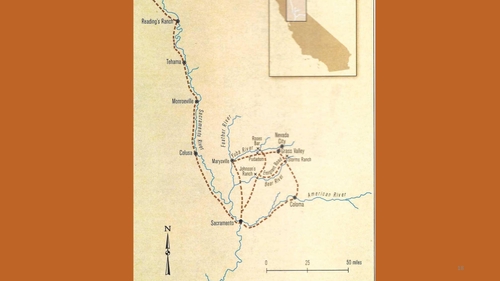

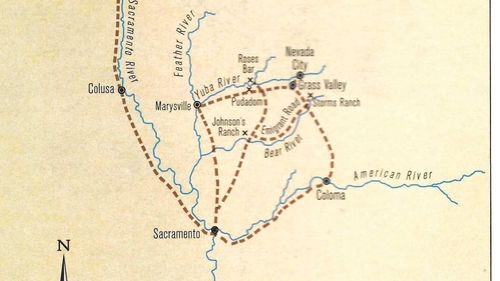

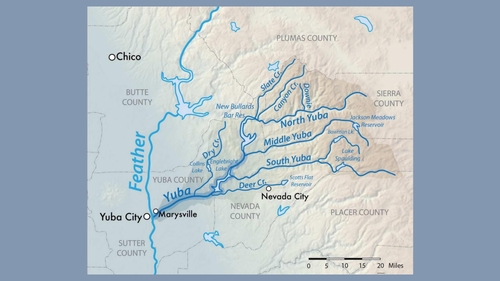

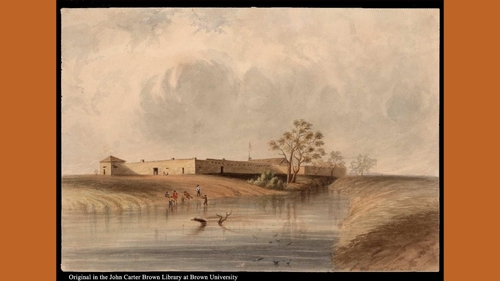

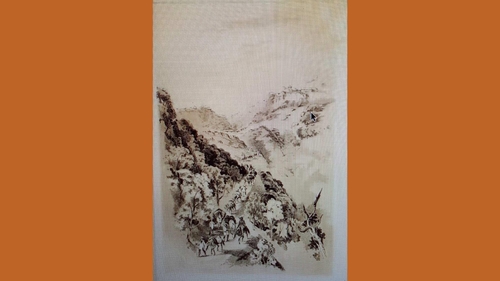

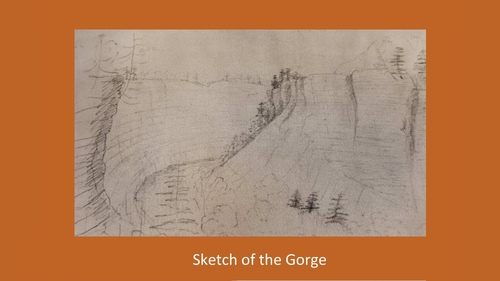

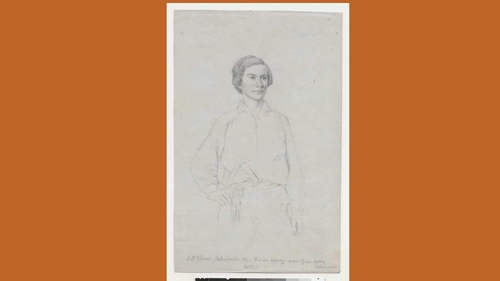

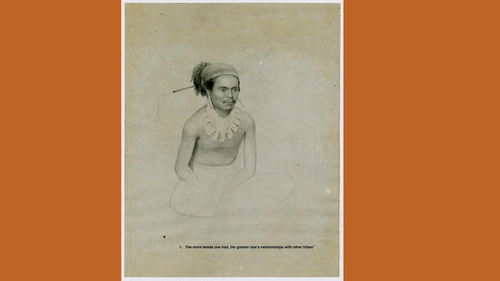

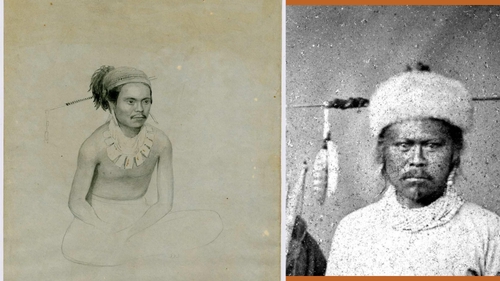

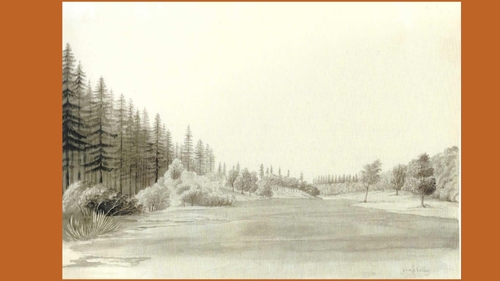

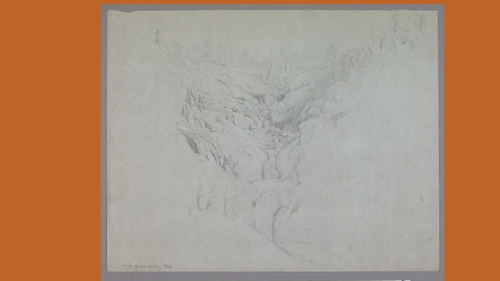

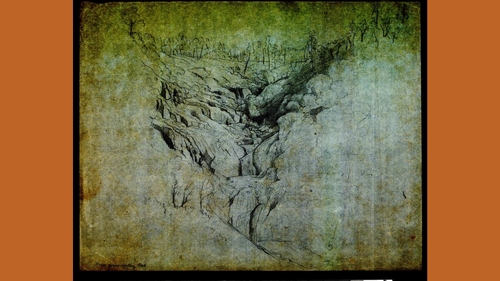

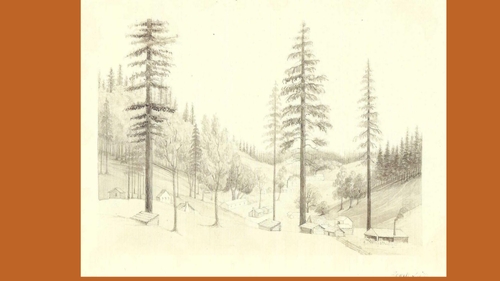

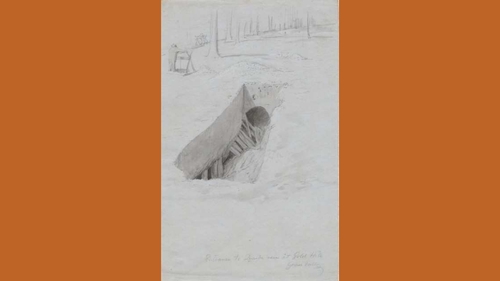

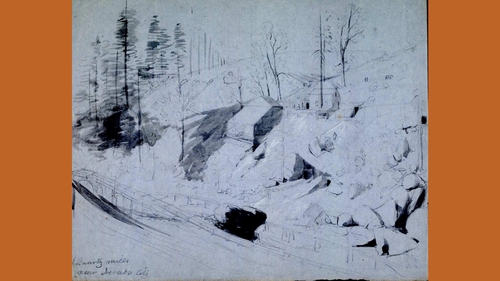

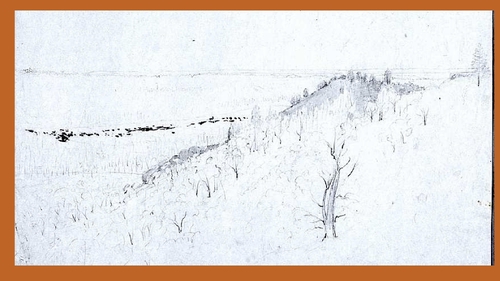

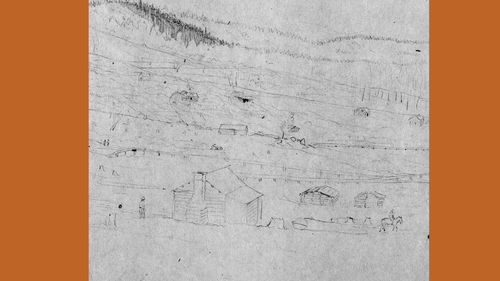

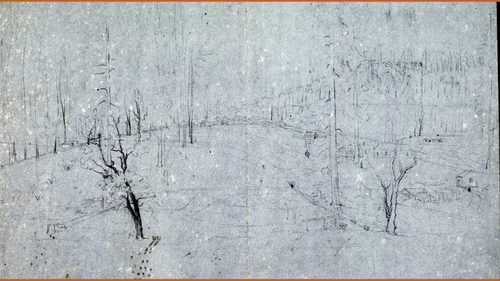

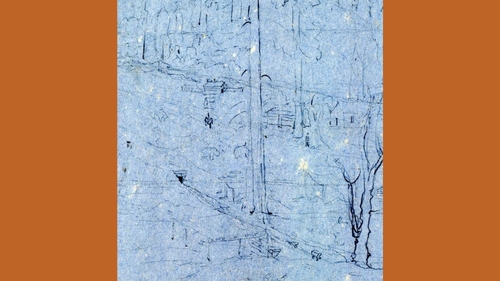

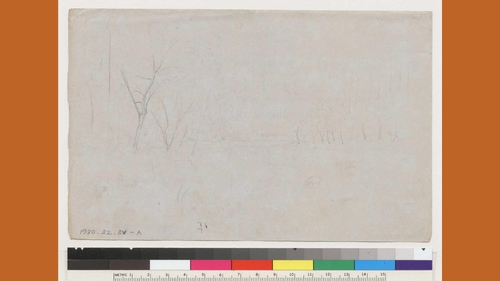

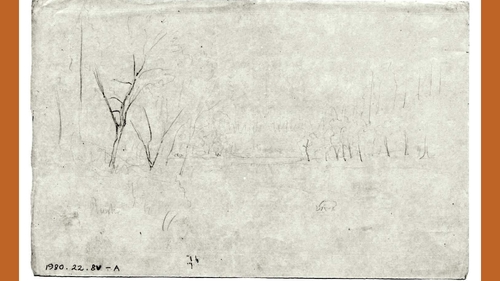

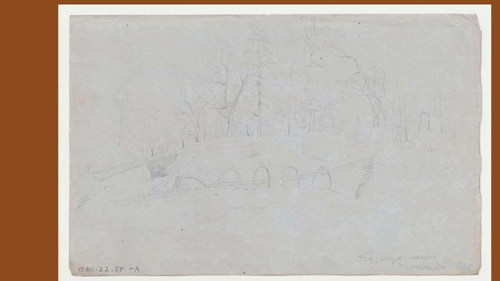

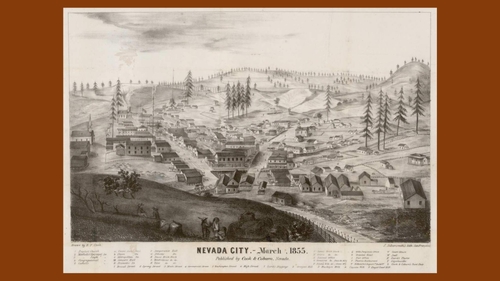

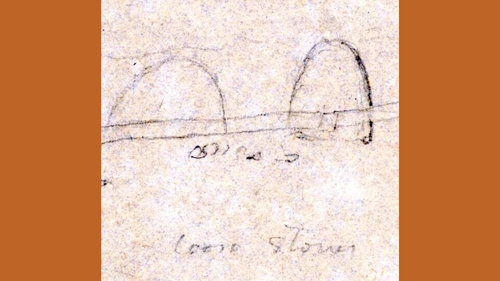

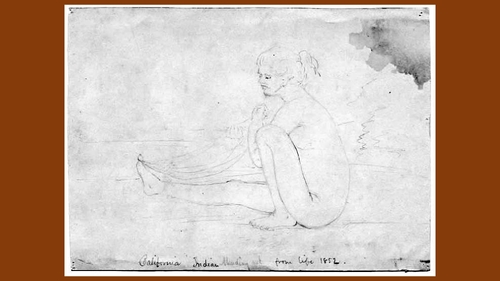

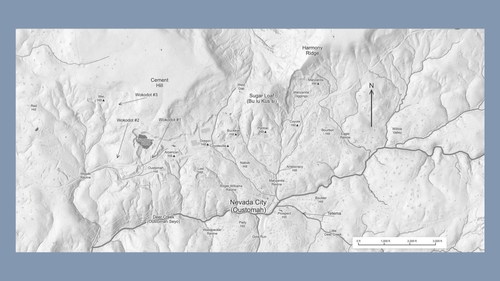

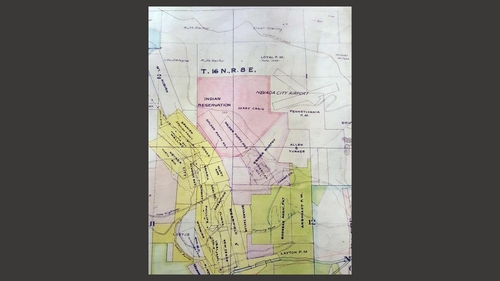

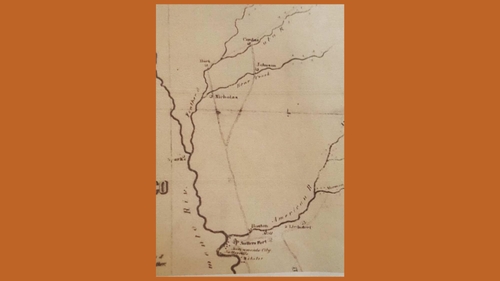

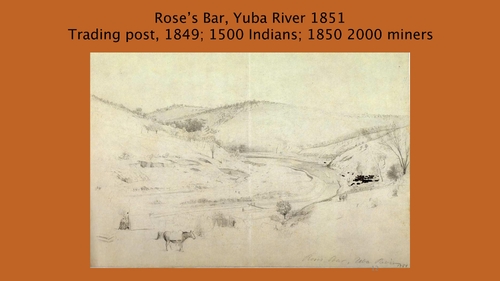

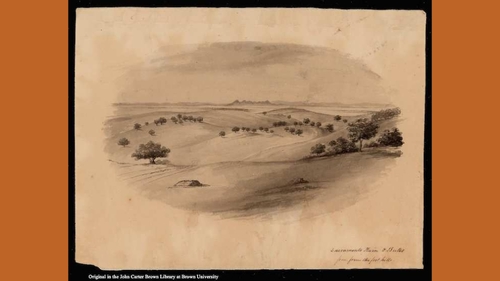

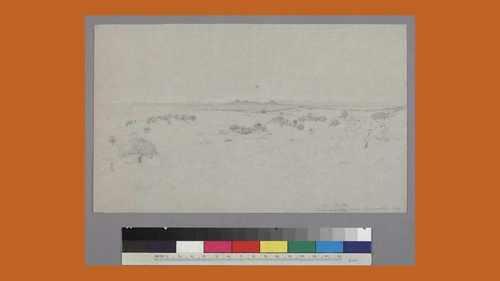

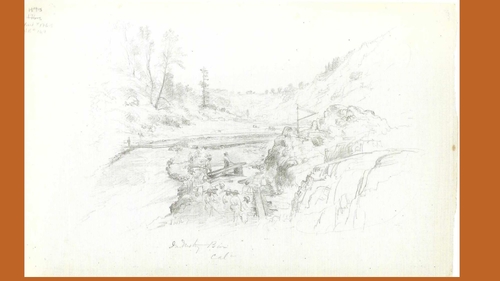

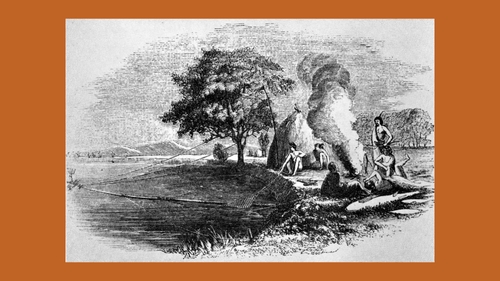

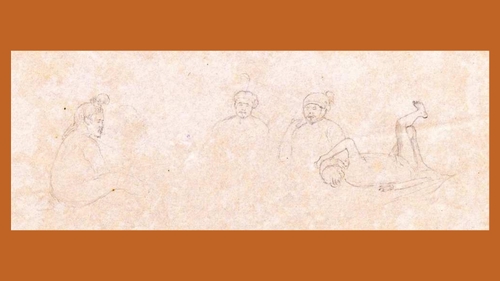

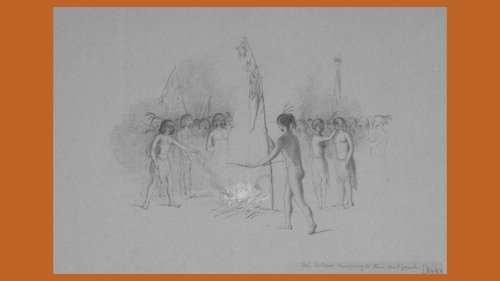

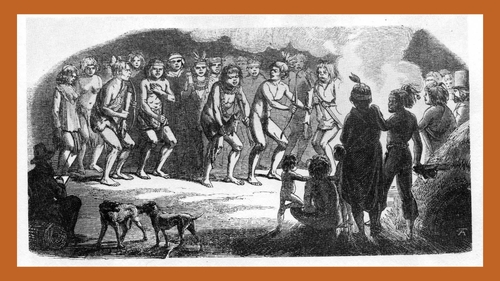

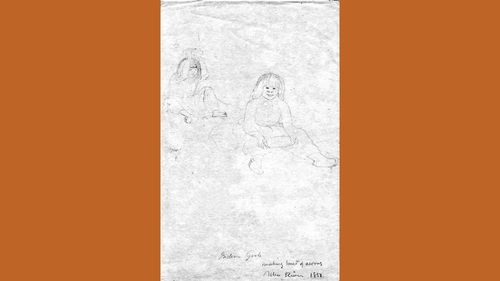

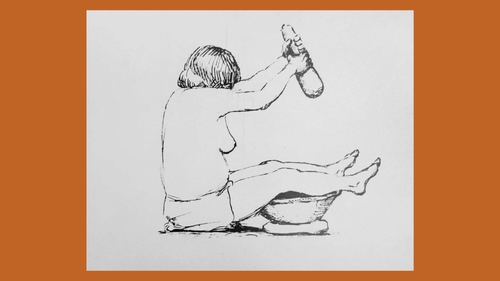

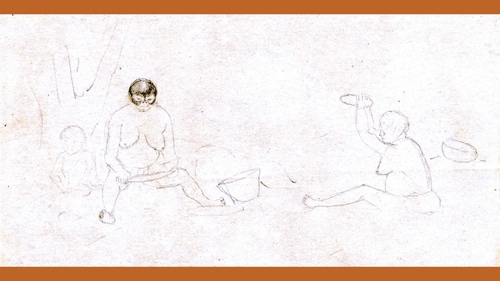

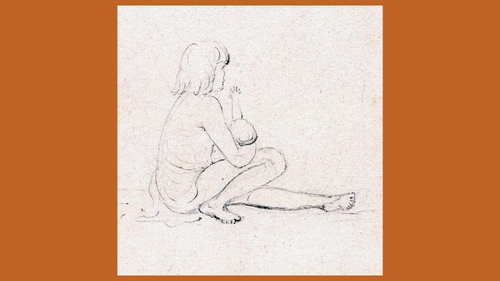

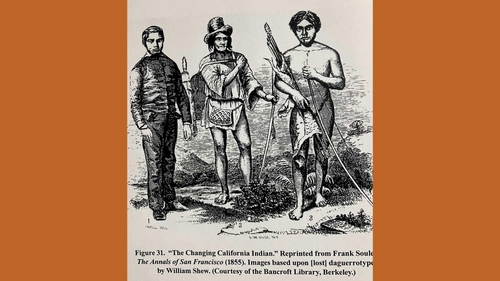

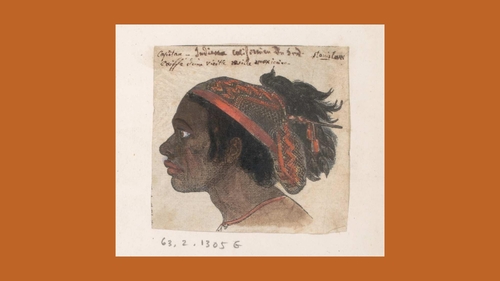

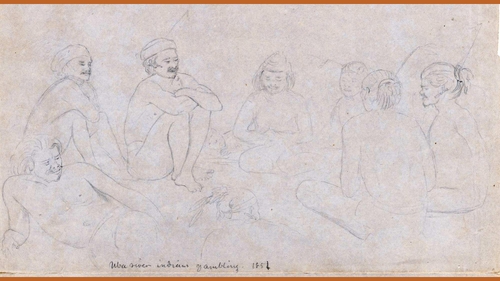

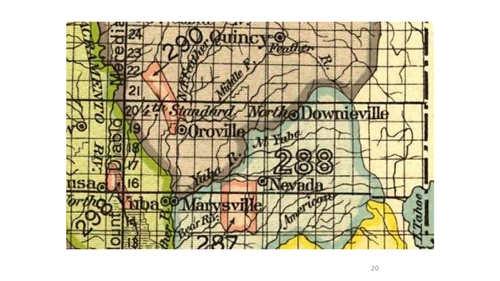

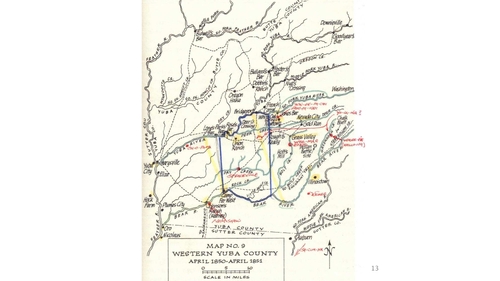

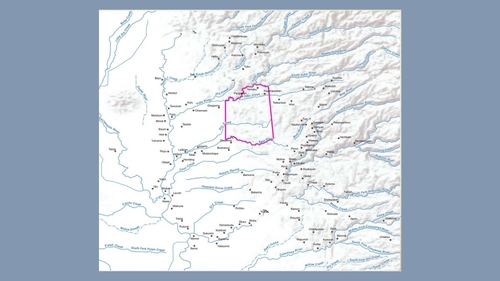

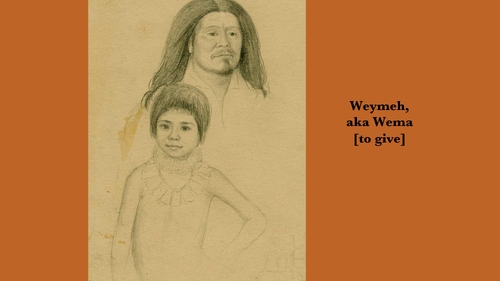

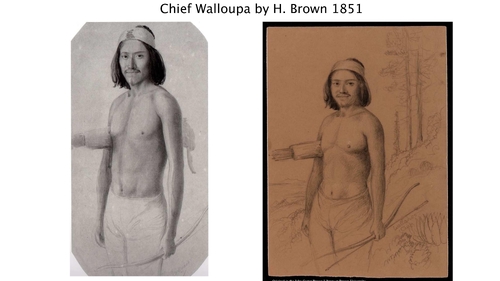

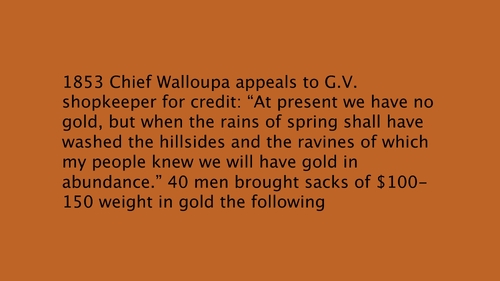

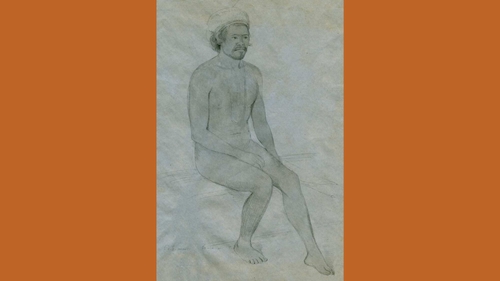

Research and there's some copies back there and I started doing research on Henry B Brown while doing the research for this book and this book has some never-before-published images of Henry B Brown in it. This is just to put a familiar, does everybody hear me? Is this loud? If I hold it like this? Okay. Just to familiarize yourself with the Nisanon territory, it's simply a synonym for Southern Maidu. Alright, so it's the southern part of the Maidu territory which we're in today and notice the Khaan Khao right above and also the Machupta Maidu. We'll be mentioning those later. These are all Maidu and speaking people. Now each journey has a point of departure and this is mine. I began my journey when I began reading David Comstock's wonderful research on this prominent Nisanon leader by the name of Wima. He spelled various ways and he, David, as you may know, fictionalized Wima in his book Gold Diggers and Khaan Followers and he also did a lot of newspaper research as many of you know and pulled out all the information about Wima. Wima was mentioned quite often. He was such a prominent Nisanon leader, regional leader, that he was called a king and somewhat facetiously Alonzo Delano, who was a Grass Valley resident and humorist, wrote a spoofing piece about Wima about actually going on a camping trip with him with Simone Storms and it's called A Sojourn with Royalty. But this one is a seriously important man. He was the major diplomat for the Nisanon major negotiator and this is a picture drawn by Henry B. Brown, both of these images. Then while I was doing research on my Nisanon book, I was looking through this book. Now Don Linders was so conscientious that he trimmed off the bottom and the top of this, but this is this image of a of a Khaan Khao village scene. It's also Henry B. Brown and Thomas Blackburn did this book in 2006 and it basically publishes some of the best Henry B. Brown pictures and in this book I found that portrait of Wima and was quite delighted to find that. There were also a picture of two other Nisanon leaders in this collection of thirty or more of Henry B. Brown's work. So I started thinking. I started looking through this book and what I noticed is that one third of Henry B. Brown's best works were from Nevada County and this amazed me. Here this very prominent, well-known artist and he did a lot of work in Nevada County. So this began an epic journey of my own to go to all the archives where Henry B. Brown's art now is and there are, it's, this work is scattered across the country in Providence, Rhode Island, at Peabody, at Harvard. Of course I didn't go there because this was during the COVID, but this is all online. Also the Huntington Library in San Marino and the Bancroft Library in, at Berkeley. So the results of that work is what I am going to show you today. Now Brown is terribly important and I'll show you a couple more image and you will see why. He is both realistic and he is empathetic and so, and these are pictures moreover are done in 1851 and 1852 and the timing is critical because this is just three years after the gold rush. So this is like very early contact period. These cultures and these populations are still intact but within five years they will have collapsed and the population and the culture is virtually gone. So Henry B. Brown is making this tour and making these images at a time when these cultures are still healthy and I want to read you a little excerpt from, there it is. All right. In Brown's Strimes, Indian villages are intact, their headmen are dignified, the people are attractive, happy, industrious, and relaxed. While conveying the immediacy and beauty of California Indian life, Brown's images are all the more precious, observes Blackburn, because they caught the ephemeral moment in time before the cataclysmic decline of Native America. So this is why this man is so terribly important and why his work is so highly rated by anthropologists and others today. Now the first question, there are several mysteries here and one of them is, who is this person? We have a name but what is his tribal affiliation? What do we know about them? Well, if we know when Brown took this picture, drew this picture and where he did it, that provides clues. So figuring out his Henry B. Brown's travels during 1851, 1852 is very important for that reason. Another mystery, how did he get access? He does pictures of people and they are relaxed. How did they trust him? How did he get their trust? There are four pictures of Nisanon chiefs, three of whom signed the Treaty of Fort Union. How did he manage to be someplace where three other chiefs were at the same time? How did he get people to cooperate? And finally, what do these images reveal about Indian culture and Indian history and the change people were going through? Now here's kind of a summary of what we know about his life. We don't know much at all. He was about 35, born in Massachusetts when he arrived in San Francisco in May of 1851. His goal was to, he wasn't a hearty soul, his goal was to do a illustrated volume and then sell it on the East Coast to people who were curious about Gold Rush, California. He takes a couple trips into the interior and he comes to California twice in 1851 at the end of the summer and the beginning of the fall. And then he's doing drawings and these are pen and ink drawings and a number of pencil drawings survive as well. Well, a man named John Russell Bartlett who was head of the border commission, US Boundary Commission, sees his work and hires Henry to make an eight-week trip up the Sacramento River, which at that point was Tara Incognito. And so, he wanted Brown to do a scientific study and document what he saw there with his drawings. And this is how Henry Brown becomes visible, historically visible, because he's part of this major boundary commission study. There are, as I explained, there's, these are the important reasons for his, for his work. And this is what I discovered, that there's about a hundred drawings in all. Some are duplicates, some are pencil drawings that are barely legible after a hundred and seventy-five years. Several of these pencil drawings are at the Huntington Library and the Bank Front Library. But about half of these are done in our area. To make a bad pun, Henry Brown was drawn to Nevada County. He was, he liked this place. And he did seventeen mining and landscape scenes in Nevada City, Grass Valley, and along the Yuba River. Ten of these are unpublished. There's also a number of ethnographic images by Brown that specifically refer to the Indian people he's drawing as Uba, or Yuba Indians. So we can place him very clearly on the boundary between Nevada County and Yuba County. And he did several Indian portraits. And I argue that the vast majority of these are Nisanon people. So what we have here is this remarkable treasure for a people who vanished from our sight so quickly in the gold rush. We have this remarkable record of the leaders and the people at that brief moment in time. Now Bartlett, as soon as, well he commissioned works from Henry B. Brown, twenty of them. And Brown, and then in 1854 Bartlett published his personal narrative, 1854, and took some of Henry Brown's pictures and turned them into woodcuts that were part of this 1854 book. But he didn't give attribution. All right? And I want you to notice something interesting about this. See this guy over here? He's rolling around in the sand right here. See how this odd figure here? Well this is a wonderful ethnographic document of fishing. But we don't know where. Here's another one of the woodcuts. And it is an interior of an Indian home. Very rare to have something like this. But it's a woodcut based on one of Brown's drawings. And here is the original from which it was taken. And these are very finely rendered. And these ended up in the Bartlett collection both at the Peabody and at the John Carter Brown Library in Providence. And they got subsumed into the Bartlett collection. Nobody knew Henry B. Brown drew them. So they were attributed to Bartlett. So for over 100 years Henry B. Brown basically vanishes from sight. But these are considered some of the best ethnographic works on California Indians in existence. This one is near Calusa. It's just a family at home. This one is probably the rarest and most exceptional because it's the only example we have of a contemporary. That is 1851, the interior of an Indian council house. And this is Patlin I believe. These were done on his trip, his eight week trip up the Sacramento River. Another very famous Brown done. And again you see Indian people in a natural state. Very contented going about their business in their, it's just, these are very rare. Now Henry B. Brown did not leave us much, but he did leave us a map that survived in the Bancroft Library. And this is the most interesting document here. What he did is he took an 1851 map and he drew a pencil mark of where? You can see his lines of where he traveled. So we got to have a clue here. All right. So it's July 1851. He's itching to go into the interior and start his books and drawings of historic California. Where would you go first? And you were going to do an illustrated book on the gold rush. Sutter sport. Right? So. And we see him going, now pencil mark right there. Going and then going straight north. And what's between Kavoma and Nevada City? Many different river canyons. Now here is a artist's, artist's rendering of that same trip, which makes it much easier. But we can see that he does, he two times or perhaps as many as four times, he comes back to Nevada City, Grass Valley. He's at Storm's Ranch and Rose's Bar. And then heads back. We don't know which direction he's going, of course. So this is something that we have to guess about. And here's a better, closer image of that. And my theory is he goes to Kavoma first. All right. And then he heads, heads north and comes to Storm's Ranch, which the hermitage at that time was the best hotel with the best food. So it was a very good place to rest for the weary travel ers after going up and down and up and down major deep river canyons. And there it is, Henry B. Brown's picture of Sutter's Fort. And here's another artist's view of Sutter's Fort, but I think Brown's is particularly lovely. All right. And then there, this is one of the woodcuts from Bartlett's book that has no attribution. But I'm guessing this might be Henry B. Brown. That he was going into those deep, you know, in a stagecoach, going down deep into these river corges, and this is one of his crimes. And another one that might be a Henry B. Brown. All right. Then he arrives at Storm's Ranch, and here is Storm's himself, Simone Pena Storms, who was, according to some reports, Wima's father-in-law. He, he married Wima's daughter, purportedly. All right. He's a very young man, but this is a very important man in Placer County, in Nevada County history. A Chicago Park area. And there was a great density of Indian population there. This is dated, and it says, "Simone Storms, 1851 Indian interpreter and Indian agent. " At this time he was a private citizen, but later he became a Indian agent and interpreter at treaties. And here, Storm's is shown next to Wima at Round Valley after the Nisanon Indians had been removed to reservation on the coast in 1855. Wima always wore this blue coat that was distributed to him at treaty sessions to fatten him up. All right. Now this is a man named Bullock, and that's all we know, but it's a particularly beautiful round portrait. And Bullock, if we put some of the ethnographic information together, we learned that this is a hereditary chief, a ancestor of the Prow family in Colfax, California. And one thing that we learned from this, I think, is it confirms that the Nisanon had hereditary chiefs, and we can tell that they are the chiefs because they have the abalone shells as a sign of their stature. And it says, a little quote at the bottom, you probably can't read it, but it says, "The more beads one had, the stronger one's relationships with other tribes. " These were the boundary players. They were multilingual. They intermered with elites of other communities to create a family of royals, and they did the trade and the diplomacy. And this man, you can see, has a very fancy headpiece there. Now here he is, and next to him, what we don't have many pictures of, I think there's only two surviving pictures of the 18, unratified treaties of 1851, but we do have a daguerreotype of the Machupta treaty, and this is a photo of one of the Mayu men who signed that treaty, and you can see the strong resemblance to Boak. And Boak, by the way, is a signature to the 1850 treaty of Fort, of Bear River. All right, next, where do you go if you're doing illustrated history? Of course, you want to go to the mines, and this is Grass Valley, when it was grass. And now we get into one of the unpublished pictures that was pencil, and pencil only. And what I discovered was that through digitalization, that is scanning these and then using Photoshop, I could get more definition. And this actually is quite an involved, of course somebody like Don could do this much better, but if you can see how much time he's been in, this is Wolf Creek. This is Wolf Creek, which I think is really, really remarkable. All right, and then he goes to Gold Hill. All right, and Gold Hill was the first quartz mine. All right, and so these are very historic images of this first quartz mine. I have a quote from, and he does it two or three drawings here at Gold Hill in Grass Valley. Charles Ferguson reports in his memoir of mining in Nevada City in the early 50s about the middle of 1851, Nevada City was startled by a midnight cry from Grass Valley. It was the quartz gold discovery, reputed to be wonderfully rich but difficult to work, though men were making good wages pounding it with mortar and pestle. Soon it was seen that some process must be devised to get the gold out easier and faster. Judge Walsh and Mr. Collins were the pioneers in the quartz mills. It was four head of stamps with wooden shanks, and the most it could do was pound out two tons of quartz in a day. The job of feeding the quartz into the mill was arduous. The joke was a patient man, said Ferguson, but he never attended a quartz mill like the first one in Grass Valley. And here is an entrance to a mine in Gold Hill. All right, onward to Nevada City. This is another quartz mill. Quartz mill near Nevada City, it says, and this has been digitally enhanced in order to get some of the detail. Then there are about six images of Nevada City from 1851-52. We know he came back. We don't, these, most of these aren't dated. This has been digitalized to bring out the color, and this is one of the finest ones. This is Sugarloaf, looking down at Deer Creek. And for some reason, he put those black marks to indicate the river. And I don't know why that is, I guess because it was being torn up, right? And so it was in an upheater, but that's how he indicated the river. And this is another one that has been digitized to bring out, and because the more you enhance, you can see more of the forest, more of the ridges. Here we're looking, I think, at Banner Ridge and Deer Creek. Here's another one before it was digitized. Huntington Library scene, doesn't look like much, but once it's digitized, you get this amazing amount of detail. And so back where Dan is, there's a printed copy of this. This is actually one half of one of these drawings. You can see Man on a Horse. There's quite a bit of detail. Of course, there's a sluice. There's trees down, obviously. But we get an image of what it was like in Nevada City in 1851-52. Here's again another pencil drawing without enhancement. But I think this is a different one, sorry, but this is. But here we see again a great deal of detail once it is enhanced. You can tell what kind of trees these are. Lots of buildings, miners, cabins, and then a whole row of miners cabins in the entrance to a mine. And there you can see all the cabins that were built right on the ridge. And this one is a meadow near Nevada City. And I'm guessing it's Pioneer Park. And once it's enhanced, we can see a cow grazing in the meadow. This one is called Diggings near Nevada County. And when I first saw this, I thought I was in heaven because I thought what we are looking at here is hobo. That is, a lot of the Nisanon structures are kind of cone-shaped like a teepee, but the winter dwellings were rounded and domed. And I thought I have found the only existing picture of a village site with an intact village site with the winter villages. And then I enhanced it. And you can see a lot more detail. But what it starts looking like, and it gets, you know, you should, you could tell from the title "Dingings" near Nevada City, that there's deconstruction going on here. There's mining and the trees are being felled. And here's a hobo right here in this 1855 map. You can see it's a very funny, you know, it's got a smoke hole at the top. And then I look closer and it says "Loose Stones. " So the laugh was on me and I was glad that I didn't brag about it, or especially didn't brag about it in print because I was so wrong. Nevada City was a center for the manufacture of nets that were traded across the region. And in fact they had a brew of certain kind of reed that was used for this very strong nets. And this is one of a fine Henry B. Brown drawing perhaps down right here in Nevada City of a man making a net. 1852. California Indian men making a net. It could be someplace else. One of the best things, takeaways from Hank Meals and my book, Nevada City Nissanam, is we developed this idea that the Nissanam were not, that they were a very mobile people. We call it the mobile metropolis. That they were constantly at the, on the move, and that they had certain urban centers. And among these were Empire Ranch, Nevada City, Colfax, Auburn. Each of these very dense urban areas, if you will. Lots of Indian communities in these places because they were particularly rich in resources. They were at locations for trade. And here's Hank's definition. We call these geo hubs. Settlements and or meeting places based on favorable topography that connects ridges and watersheds where trails converge. These trails access different ecosystems and different elevations. These were typically places of abundance adjacent to springs and wetlands and were favorable places for trade, ceremonial events, and social transactions. And Nevada City has had a very long-lasting Indian community. And my argument is that it was because this was a hub here in Nevada City. And here's the villages of, village of Waukadot that later became an Indian reservation. They were continually relocated. This is a Don Lenders map, by the way. And they had, they had a permanent settlement that later became a reservation out there on cement hill. All right, moving on. Now there was quite a bit of movement. Seasonal movement up and down Deer Creek. And this is out of place, but there's the Indian reservation up there, five in the Nevada City airport that was there until the 1860s. Now we're in, now we're down there near Smartville. And Smartville, there was a village there called Pudadom. And that was the area where they had annual burning celebrations. And Nevada City also was one such place. Now this is an early map by Derby. And what you can see here is he has Digger here. And I don't think he means miners. I think there's a concentration, this is Rose's Bar right here. And this is probably where Indians were for wintering during that tumultuous period in the Gold Rush. And this shows some early map where, you know, dating back to the 1840s and Sutter's time, this was one of the early ranchos, Cordua's Rancho near Rose's Bar. And the main travel route was through Johnson's Ranch up to Cordua's Ranch. And this is, you know, down here in Sacramento. And so my theory is that after Henry Brown went up and down and up and down in that bumpy stage in that, through those winter counter count, through those river canyons, he was going to do that again. He took this road. This was the established road. And it took him to Rose's Bar, which at that point in time, and here is a picture of Rose's Bar, 1851. And at that time, many Indians were there and they were largely imploed, engaged in mining themselves, either as employees or independently. And again, we can see that, I mean, what do you make of that, that little, you know, this little black area? And Sierra Sutter-Bewds. He does two or three different images. Sometimes he reworked an image, and this was one of his favorites. And so this is from Smartsville, basically from that area. And here's his, one of his originals. This Sierra of Ewes. Industry Bar, which was right up from Rose's Bar. This is a mining scene, 1851, 1852. Now we're back to this woodcut, this mysterious woodcut that was included in Bartlett's personal narrative. And we have no idea who the artist is, because Bartlett didn't say. But look, here's a Henry B. Brown drawing, and look at here, look who's here. The same, he's reworking these. All right, and this was, the bankroll has lots and lots of pencil drawings that are barely legible, but once they're digitized, you get some interesting things. And here probably is one of the finest, one of the rarest, and one of the best ethnographic images of Henry B. Brown. And it's a morning ceremony. And they are sacrificing, and they are painting the women's heads with tar and ash as part of the grieving process. And in the back, you can see people singing. So this indicates to me that he was either in Nevada City when this was going on, or he was at Pudadon near the Yuba River. And this is a picture of a Indian fan mango. They were quite common throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s. People still got together. Here's a couple images of Indian girls making a bread of acorns, Yuba River, 1851. And look, the little girl is smiling, how did he get them to trust him? How did he get so close to these people? Here's a picture that was very faint. And then once digitized, we see this woman has the morning ashes on her head. And it isn't just random, plopped some ashes on someone's head. It was very artfully done. It was the line of the ash and the tar was brought underneath her cheek. And I think so that when she's cried, that there would be all the more black stuff dribbling down her downward face. And this is one of my favorites, this small child reaching up, hopefully, into the sky. And again, another never published before, Henry Brown. And it's very different from his other work. And we don't know where it is, but there is an American standing here and he is shielding a child. And this man is trying to moderate, this man is clearly quite angry. What's very curious is that this woman has a Sioux Indian hairdo. That this woman does not look like she is a local. She looks like she's one of the people who came in with the fur traders. Another woman and child. And this is an image done very early in time. And I think it, and the message, and it's usually been interpreted as how Indians assimilation into white society is inevitable that they were doomed, they had to assimilate or die. But I think there's another way to read this. I think it shows how quickly the Nisanon had to adapt or die. In weeks, months, years, they had to adapt their way of life. And that meant working for heading up work parties that worked for miners. This is not a brown, but it's a wonderful picture of a Indian chief with a beautiful headdress, a native headdress on the Stanislaus River, a Yuba River Indian gambling. This man is holding the little pegs behind his back and these people are trying to guess. And what this, we discover something the closer we look at that. And that is, this says Yuba River Indians gambling. So we know this was down at Smartsville Roses Bar area where Henry B. Brown was. But it turns out he did portraits of these same individuals. So we know they were on the Yuba River too. That they were Yuba River Indians. So this places a lot of different portraits in Nevada County and Yuba County. Now the clear supposition is that Brown must have been at the Fort Union Treaty of 1851 and that's how he happened to be able to see a lot of chiefs and a lot of people were gathered there. And that's how he got to do this. Well this is for those of you who are probably aware of this. 18 unratified treaties in California. The federal government had a policy and it was you have to buy Indians land before it can be distributed to white people. All right. So, or before white settlers can move in. So the federal government was a little late but 1851, they came in and they started negotiating treaties with the Indians. And one of the groups they negotiated with in this area called 2288 is the Nisanon or the Southern Miter. And what's going on here is their territory is being surrendered. They want them out of the Goldridge, Red Bridge territory. So and then they're going to agree to stay in this area right here. And same thing up at 290. This is all being surrendered so but the Indians are reserving this part in this reserve area as well. All right. And here's another rendition of this. And a lot of the richest gold area indeed was outside the treaty area. But look at this. It's bounded on the north by the Yuda River and the south by the Bear River which are full of gold. And also this is very rich. But here is Union Ranch where that treaty was negotiated. Right there. 1851. Another rendition of that. That treaty boundary. Now the senate did not ratify this. So this reservation did not occur. Here was one of the signatures. And what can we learn about these men from these images? Are there clues here? Now clearly the child, either a girl or a boy, is a member of the elite. But Wima has no ornamentation. He shows a a culturation and he has on a white man's clothes. He was the chief signator at that treaty. Here I think this looks a lot like him. Oh, I think this was his daughter possibly married to storms. Here's another signature to the 1851 treaty. Walupa. For whom the town Walupa is named. And there's two versions of this. And you're going, well where was this picture? Where was this drawn? Well can you see what's in the background here? The slope and the looks here in the background. It's the it's the setter views. This was done at at Smartsville at the Union Ranch. Clearly right there. Walupa is famous in Grass Valley history for this well-documented incident in which he, you know, Indians are basically surviving by the gold dust they're collecting. And the people are starving. So he goes to a shopkeeper and promises to bring back gold after they have a chance to gather some. And they did. 40 men brought in sacks of 100 to 150 weight in gold in the following year. Here's another signature to the Fort Union treaty. And again what's in the background? The setter views and then the upland there. So it's that it's that eco tone between these two places. And there's a couple pictures. But we know from here was one of those pictures of a portraits of a man who was in the the gambling picture. We know that Henry B Brown couldn't have been at the treaty. I think this Tacoma is this guy. There's a similarity in the facial stroke. [Applause] Do you have any questions? Yes. I'm curious. Well Mr. Proud, Clyde Proud, who is the descendant of Bullock, was very excited about it. And I did share these at a Nisenon event last year. Yeah they're they're aware. They're aware of it. This this publication goes in deeper to what happened at the Treaty of Fort Union. As you know, the Nisenon says our land was never ceded. The treaties were never ratified. And this article goes deeper into what happened there. And my theory is is that these particular Nisenon leaders were pretty sophisticated. They've been dealing with traders for some time. And they got the best of the negotiator and got an absolutely fabulous reservation that had gold on one side and gold on the other. And if you want to hear the sort of the nuanced story of what I what I think I've learned from what happened there at the Fort Union Treaty, please take a look at this. And I think the very fact that they got a fabulous reservation that had gold deposits on it, perhaps doomed all 18 treaties. Because they couldn't, it was such a good reservation, they couldn't ratify that treaty. There was a huge uproar and opposition to it in Nevada County. Penn Valley was located in the middle of it and that was valuable for grazing. And it's just, I think, Nevada Countians were very instrumental in getting the treaty rejected and the other 17 went on. Yeah. And before many gatherings in this area, the hosts will pay homage to the indigenous of the region. And I've heard some debate what in favor and out of favor of doing such a thing. I'd be curious to hear your perspective. I'm sorry, I didn't quite understand what you said. So when meetings are held, yes, the host will typically say offer homage to the indigenous. We are on Nisenon land. I'd like to hear your perspective on that. I've heard debates in favor and out of favor of doing such an homage. You know, I see, I've been doing Native American studies for 20, 30 years and I've seen this transition. I first started in New Zealand and Australia, Pacific Islanders. I just don't do it myself. I guess I'm just kind of an old school academic and I don't oppose it, but I just don't do it myself. But from Nisenon's perspective, do you, do you, can you enlighten us on the purpose of it? Oh, the purpose of it. I think it's pretty straightforward that this was indigenous land and we have to be aware of the people who were the first people here. Is it insulting to them? Oh no, no, no, no, no, no. Because I think Shelley and the, and the Rancheria people feel like this is unceded land, it's still theirs. You know, that's another reason to, to, you know, make this front and center in people's consciousness. And as many of the images, the sketched images show the complexion is being pretty light, yet we see photographs that are in fact very dark. What are your thoughts on that? Do you think that was purposely done by the artist? I think it depends on the time of the year. But, and I think this particular artist, can you say, or is it medium? Yeah. Have you found any journals from any of the men that were written around and traveled that might add some more inspiration? No, we've looked and looked and others have looked as well. And Tom Blackburn does a great job of kind of sorting out what happened and who he was and where he went and based on the available information. And what I did is I just further nuanced it a little bit by explaining how important Henry B. Brown was to Nevada County, specifically to the Nisarn people, because the Sacramento Valley pictures are just thought to be his very best. But I think some of these Nevada County and Nisarn pictures should get their recognition as well. Yeah. What brought Henry Brown here? Was he looking for gold like everybody else? No, no, no. He was kind of sickly. And I think he was about 35 years old, unmarried. We hardly know anything about him, but like many people, oh, he, he, one of his relatives was assigned to be the U. S. postmaster in San Francisco. So he came along with his, his relative for the adventure. And that's where he was based. So yeah, you said were there any journals? There was a little bit of family history and a few documents have come up. He gave a number of his pictures to his cousin for safekeeping. And then she put her name on it and said these are my drawings. And then that created all kinds of confusion for, for a while. So yeah, but there's just little tiny bits of information. But, but we're, you know, I think maybe more will be revealed. Many pictures were, didn't come to light until 1920 when they were given to Sea Heart, Miriam. Maybe other people have collections of Henry B. Brown pictures, you know, and, and they will donate them or they have letters or something. I mean, this is, it's possible. Do you know how long did he live after this? He, he, we think just till 1860. He died very young. He was at a consulate. There's some pictures showing that he ended up in a consulate in the Bahamas or something. He went home to Massachusetts once, but then, you know, he fades from sight. Now the pictures that were donated to Sea Heart, Miriam by an anonymous source, I think was the person or persons who were living with him when he died and inherited his stuff and hung on to it. Like a lot of us parents hang on to the very first drawings of our kids, those first little, you know, they treasured every single one of these pencil drawings and kept them and preserved them for a number of years and then anonymously donated them. And then they felt, they came into the, the bank rock and the Huntington. So, I mean, it's a miracle that they survived. [Audience member] Do you have any theories personally on how you think he obtains to intimate portraits and like scenes of losing his Well, I think he came to a, the morning ceremony. And these morning ceremonies were typically three or four day events. They were done at the time of salmon runs, so there was lots of food, lots of acorns being harvested. People are, are, are gambling, they're feasting, they're in a happy, relaxed food, and there's lots of people gathered together. And so I think that explains why. But, but how he got all these people to cooperate, I don't know. He must have been a very, very gentle soul. [Audience member] Do we know his training in Parkville at all? Did he sell thought or did he have any formal education? Not much, not much. Just scraps of information. Can I just get some books for sale? Yeah, there's some, I have some of these for sale for $30, and this is $15, and there's Nevada City Neeson on, which is a companion piece to this. So they're back in the corner if you're interested.

Research and there's some copies back there and I started doing research on Henry B Brown while doing the research for this book and this book has some never-before-published images of Henry B Brown in it. This is just to put a familiar, does everybody hear me? Is this loud? If I hold it like this? Okay. Just to familiarize yourself with the Nisanon territory, it's simply a synonym for Southern Maidu. Alright, so it's the southern part of the Maidu territory which we're in today and notice the Khaan Khao right above and also the Machupta Maidu. We'll be mentioning those later. These are all Maidu and speaking people. Now each journey has a point of departure and this is mine. I began my journey when I began reading David Comstock's wonderful research on this prominent Nisanon leader by the name of Wima. He spelled various ways and he, David, as you may know, fictionalized Wima in his book Gold Diggers and Khaan Followers and he also did a lot of newspaper research as many of you know and pulled out all the information about Wima. Wima was mentioned quite often. He was such a prominent Nisanon leader, regional leader, that he was called a king and somewhat facetiously Alonzo Delano, who was a Grass Valley resident and humorist, wrote a spoofing piece about Wima about actually going on a camping trip with him with Simone Storms and it's called A Sojourn with Royalty. But this one is a seriously important man. He was the major diplomat for the Nisanon major negotiator and this is a picture drawn by Henry B. Brown, both of these images. Then while I was doing research on my Nisanon book, I was looking through this book. Now Don Linders was so conscientious that he trimmed off the bottom and the top of this, but this is this image of a of a Khaan Khao village scene. It's also Henry B. Brown and Thomas Blackburn did this book in 2006 and it basically publishes some of the best Henry B. Brown pictures and in this book I found that portrait of Wima and was quite delighted to find that. There were also a picture of two other Nisanon leaders in this collection of thirty or more of Henry B. Brown's work. So I started thinking. I started looking through this book and what I noticed is that one third of Henry B. Brown's best works were from Nevada County and this amazed me. Here this very prominent, well-known artist and he did a lot of work in Nevada County. So this began an epic journey of my own to go to all the archives where Henry B. Brown's art now is and there are, it's, this work is scattered across the country in Providence, Rhode Island, at Peabody, at Harvard. Of course I didn't go there because this was during the COVID, but this is all online. Also the Huntington Library in San Marino and the Bancroft Library in, at Berkeley. So the results of that work is what I am going to show you today. Now Brown is terribly important and I'll show you a couple more image and you will see why. He is both realistic and he is empathetic and so, and these are pictures moreover are done in 1851 and 1852 and the timing is critical because this is just three years after the gold rush. So this is like very early contact period. These cultures and these populations are still intact but within five years they will have collapsed and the population and the culture is virtually gone. So Henry B. Brown is making this tour and making these images at a time when these cultures are still healthy and I want to read you a little excerpt from, there it is. All right. In Brown's Strimes, Indian villages are intact, their headmen are dignified, the people are attractive, happy, industrious, and relaxed. While conveying the immediacy and beauty of California Indian life, Brown's images are all the more precious, observes Blackburn, because they caught the ephemeral moment in time before the cataclysmic decline of Native America. So this is why this man is so terribly important and why his work is so highly rated by anthropologists and others today. Now the first question, there are several mysteries here and one of them is, who is this person? We have a name but what is his tribal affiliation? What do we know about them? Well, if we know when Brown took this picture, drew this picture and where he did it, that provides clues. So figuring out his Henry B. Brown's travels during 1851, 1852 is very important for that reason. Another mystery, how did he get access? He does pictures of people and they are relaxed. How did they trust him? How did he get their trust? There are four pictures of Nisanon chiefs, three of whom signed the Treaty of Fort Union. How did he manage to be someplace where three other chiefs were at the same time? How did he get people to cooperate? And finally, what do these images reveal about Indian culture and Indian history and the change people were going through? Now here's kind of a summary of what we know about his life. We don't know much at all. He was about 35, born in Massachusetts when he arrived in San Francisco in May of 1851. His goal was to, he wasn't a hearty soul, his goal was to do a illustrated volume and then sell it on the East Coast to people who were curious about Gold Rush, California. He takes a couple trips into the interior and he comes to California twice in 1851 at the end of the summer and the beginning of the fall. And then he's doing drawings and these are pen and ink drawings and a number of pencil drawings survive as well. Well, a man named John Russell Bartlett who was head of the border commission, US Boundary Commission, sees his work and hires Henry to make an eight-week trip up the Sacramento River, which at that point was Tara Incognito. And so, he wanted Brown to do a scientific study and document what he saw there with his drawings. And this is how Henry Brown becomes visible, historically visible, because he's part of this major boundary commission study. There are, as I explained, there's, these are the important reasons for his, for his work. And this is what I discovered, that there's about a hundred drawings in all. Some are duplicates, some are pencil drawings that are barely legible after a hundred and seventy-five years. Several of these pencil drawings are at the Huntington Library and the Bank Front Library. But about half of these are done in our area. To make a bad pun, Henry Brown was drawn to Nevada County. He was, he liked this place. And he did seventeen mining and landscape scenes in Nevada City, Grass Valley, and along the Yuba River. Ten of these are unpublished. There's also a number of ethnographic images by Brown that specifically refer to the Indian people he's drawing as Uba, or Yuba Indians. So we can place him very clearly on the boundary between Nevada County and Yuba County. And he did several Indian portraits. And I argue that the vast majority of these are Nisanon people. So what we have here is this remarkable treasure for a people who vanished from our sight so quickly in the gold rush. We have this remarkable record of the leaders and the people at that brief moment in time. Now Bartlett, as soon as, well he commissioned works from Henry B. Brown, twenty of them. And Brown, and then in 1854 Bartlett published his personal narrative, 1854, and took some of Henry Brown's pictures and turned them into woodcuts that were part of this 1854 book. But he didn't give attribution. All right? And I want you to notice something interesting about this. See this guy over here? He's rolling around in the sand right here. See how this odd figure here? Well this is a wonderful ethnographic document of fishing. But we don't know where. Here's another one of the woodcuts. And it is an interior of an Indian home. Very rare to have something like this. But it's a woodcut based on one of Brown's drawings. And here is the original from which it was taken. And these are very finely rendered. And these ended up in the Bartlett collection both at the Peabody and at the John Carter Brown Library in Providence. And they got subsumed into the Bartlett collection. Nobody knew Henry B. Brown drew them. So they were attributed to Bartlett. So for over 100 years Henry B. Brown basically vanishes from sight. But these are considered some of the best ethnographic works on California Indians in existence. This one is near Calusa. It's just a family at home. This one is probably the rarest and most exceptional because it's the only example we have of a contemporary. That is 1851, the interior of an Indian council house. And this is Patlin I believe. These were done on his trip, his eight week trip up the Sacramento River. Another very famous Brown done. And again you see Indian people in a natural state. Very contented going about their business in their, it's just, these are very rare. Now Henry B. Brown did not leave us much, but he did leave us a map that survived in the Bancroft Library. And this is the most interesting document here. What he did is he took an 1851 map and he drew a pencil mark of where? You can see his lines of where he traveled. So we got to have a clue here. All right. So it's July 1851. He's itching to go into the interior and start his books and drawings of historic California. Where would you go first? And you were going to do an illustrated book on the gold rush. Sutter sport. Right? So. And we see him going, now pencil mark right there. Going and then going straight north. And what's between Kavoma and Nevada City? Many different river canyons. Now here is a artist's, artist's rendering of that same trip, which makes it much easier. But we can see that he does, he two times or perhaps as many as four times, he comes back to Nevada City, Grass Valley. He's at Storm's Ranch and Rose's Bar. And then heads back. We don't know which direction he's going, of course. So this is something that we have to guess about. And here's a better, closer image of that. And my theory is he goes to Kavoma first. All right. And then he heads, heads north and comes to Storm's Ranch, which the hermitage at that time was the best hotel with the best food. So it was a very good place to rest for the weary travel ers after going up and down and up and down major deep river canyons. And there it is, Henry B. Brown's picture of Sutter's Fort. And here's another artist's view of Sutter's Fort, but I think Brown's is particularly lovely. All right. And then there, this is one of the woodcuts from Bartlett's book that has no attribution. But I'm guessing this might be Henry B. Brown. That he was going into those deep, you know, in a stagecoach, going down deep into these river corges, and this is one of his crimes. And another one that might be a Henry B. Brown. All right. Then he arrives at Storm's Ranch, and here is Storm's himself, Simone Pena Storms, who was, according to some reports, Wima's father-in-law. He, he married Wima's daughter, purportedly. All right. He's a very young man, but this is a very important man in Placer County, in Nevada County history. A Chicago Park area. And there was a great density of Indian population there. This is dated, and it says, "Simone Storms, 1851 Indian interpreter and Indian agent. " At this time he was a private citizen, but later he became a Indian agent and interpreter at treaties. And here, Storm's is shown next to Wima at Round Valley after the Nisanon Indians had been removed to reservation on the coast in 1855. Wima always wore this blue coat that was distributed to him at treaty sessions to fatten him up. All right. Now this is a man named Bullock, and that's all we know, but it's a particularly beautiful round portrait. And Bullock, if we put some of the ethnographic information together, we learned that this is a hereditary chief, a ancestor of the Prow family in Colfax, California. And one thing that we learned from this, I think, is it confirms that the Nisanon had hereditary chiefs, and we can tell that they are the chiefs because they have the abalone shells as a sign of their stature. And it says, a little quote at the bottom, you probably can't read it, but it says, "The more beads one had, the stronger one's relationships with other tribes. " These were the boundary players. They were multilingual. They intermered with elites of other communities to create a family of royals, and they did the trade and the diplomacy. And this man, you can see, has a very fancy headpiece there. Now here he is, and next to him, what we don't have many pictures of, I think there's only two surviving pictures of the 18, unratified treaties of 1851, but we do have a daguerreotype of the Machupta treaty, and this is a photo of one of the Mayu men who signed that treaty, and you can see the strong resemblance to Boak. And Boak, by the way, is a signature to the 1850 treaty of Fort, of Bear River. All right, next, where do you go if you're doing illustrated history? Of course, you want to go to the mines, and this is Grass Valley, when it was grass. And now we get into one of the unpublished pictures that was pencil, and pencil only. And what I discovered was that through digitalization, that is scanning these and then using Photoshop, I could get more definition. And this actually is quite an involved, of course somebody like Don could do this much better, but if you can see how much time he's been in, this is Wolf Creek. This is Wolf Creek, which I think is really, really remarkable. All right, and then he goes to Gold Hill. All right, and Gold Hill was the first quartz mine. All right, and so these are very historic images of this first quartz mine. I have a quote from, and he does it two or three drawings here at Gold Hill in Grass Valley. Charles Ferguson reports in his memoir of mining in Nevada City in the early 50s about the middle of 1851, Nevada City was startled by a midnight cry from Grass Valley. It was the quartz gold discovery, reputed to be wonderfully rich but difficult to work, though men were making good wages pounding it with mortar and pestle. Soon it was seen that some process must be devised to get the gold out easier and faster. Judge Walsh and Mr. Collins were the pioneers in the quartz mills. It was four head of stamps with wooden shanks, and the most it could do was pound out two tons of quartz in a day. The job of feeding the quartz into the mill was arduous. The joke was a patient man, said Ferguson, but he never attended a quartz mill like the first one in Grass Valley. And here is an entrance to a mine in Gold Hill. All right, onward to Nevada City. This is another quartz mill. Quartz mill near Nevada City, it says, and this has been digitally enhanced in order to get some of the detail. Then there are about six images of Nevada City from 1851-52. We know he came back. We don't, these, most of these aren't dated. This has been digitalized to bring out the color, and this is one of the finest ones. This is Sugarloaf, looking down at Deer Creek. And for some reason, he put those black marks to indicate the river. And I don't know why that is, I guess because it was being torn up, right? And so it was in an upheater, but that's how he indicated the river. And this is another one that has been digitized to bring out, and because the more you enhance, you can see more of the forest, more of the ridges. Here we're looking, I think, at Banner Ridge and Deer Creek. Here's another one before it was digitized. Huntington Library scene, doesn't look like much, but once it's digitized, you get this amazing amount of detail. And so back where Dan is, there's a printed copy of this. This is actually one half of one of these drawings. You can see Man on a Horse. There's quite a bit of detail. Of course, there's a sluice. There's trees down, obviously. But we get an image of what it was like in Nevada City in 1851-52. Here's again another pencil drawing without enhancement. But I think this is a different one, sorry, but this is. But here we see again a great deal of detail once it is enhanced. You can tell what kind of trees these are. Lots of buildings, miners, cabins, and then a whole row of miners cabins in the entrance to a mine. And there you can see all the cabins that were built right on the ridge. And this one is a meadow near Nevada City. And I'm guessing it's Pioneer Park. And once it's enhanced, we can see a cow grazing in the meadow. This one is called Diggings near Nevada County. And when I first saw this, I thought I was in heaven because I thought what we are looking at here is hobo. That is, a lot of the Nisanon structures are kind of cone-shaped like a teepee, but the winter dwellings were rounded and domed. And I thought I have found the only existing picture of a village site with an intact village site with the winter villages. And then I enhanced it. And you can see a lot more detail. But what it starts looking like, and it gets, you know, you should, you could tell from the title "Dingings" near Nevada City, that there's deconstruction going on here. There's mining and the trees are being felled. And here's a hobo right here in this 1855 map. You can see it's a very funny, you know, it's got a smoke hole at the top. And then I look closer and it says "Loose Stones. " So the laugh was on me and I was glad that I didn't brag about it, or especially didn't brag about it in print because I was so wrong. Nevada City was a center for the manufacture of nets that were traded across the region. And in fact they had a brew of certain kind of reed that was used for this very strong nets. And this is one of a fine Henry B. Brown drawing perhaps down right here in Nevada City of a man making a net. 1852. California Indian men making a net. It could be someplace else. One of the best things, takeaways from Hank Meals and my book, Nevada City Nissanam, is we developed this idea that the Nissanam were not, that they were a very mobile people. We call it the mobile metropolis. That they were constantly at the, on the move, and that they had certain urban centers. And among these were Empire Ranch, Nevada City, Colfax, Auburn. Each of these very dense urban areas, if you will. Lots of Indian communities in these places because they were particularly rich in resources. They were at locations for trade. And here's Hank's definition. We call these geo hubs. Settlements and or meeting places based on favorable topography that connects ridges and watersheds where trails converge. These trails access different ecosystems and different elevations. These were typically places of abundance adjacent to springs and wetlands and were favorable places for trade, ceremonial events, and social transactions. And Nevada City has had a very long-lasting Indian community. And my argument is that it was because this was a hub here in Nevada City. And here's the villages of, village of Waukadot that later became an Indian reservation. They were continually relocated. This is a Don Lenders map, by the way. And they had, they had a permanent settlement that later became a reservation out there on cement hill. All right, moving on. Now there was quite a bit of movement. Seasonal movement up and down Deer Creek. And this is out of place, but there's the Indian reservation up there, five in the Nevada City airport that was there until the 1860s. Now we're in, now we're down there near Smartville. And Smartville, there was a village there called Pudadom. And that was the area where they had annual burning celebrations. And Nevada City also was one such place. Now this is an early map by Derby. And what you can see here is he has Digger here. And I don't think he means miners. I think there's a concentration, this is Rose's Bar right here. And this is probably where Indians were for wintering during that tumultuous period in the Gold Rush. And this shows some early map where, you know, dating back to the 1840s and Sutter's time, this was one of the early ranchos, Cordua's Rancho near Rose's Bar. And the main travel route was through Johnson's Ranch up to Cordua's Ranch. And this is, you know, down here in Sacramento. And so my theory is that after Henry Brown went up and down and up and down in that bumpy stage in that, through those winter counter count, through those river canyons, he was going to do that again. He took this road. This was the established road. And it took him to Rose's Bar, which at that point in time, and here is a picture of Rose's Bar, 1851. And at that time, many Indians were there and they were largely imploed, engaged in mining themselves, either as employees or independently. And again, we can see that, I mean, what do you make of that, that little, you know, this little black area? And Sierra Sutter-Bewds. He does two or three different images. Sometimes he reworked an image, and this was one of his favorites. And so this is from Smartsville, basically from that area. And here's his, one of his originals. This Sierra of Ewes. Industry Bar, which was right up from Rose's Bar. This is a mining scene, 1851, 1852. Now we're back to this woodcut, this mysterious woodcut that was included in Bartlett's personal narrative. And we have no idea who the artist is, because Bartlett didn't say. But look, here's a Henry B. Brown drawing, and look at here, look who's here. The same, he's reworking these. All right, and this was, the bankroll has lots and lots of pencil drawings that are barely legible, but once they're digitized, you get some interesting things. And here probably is one of the finest, one of the rarest, and one of the best ethnographic images of Henry B. Brown. And it's a morning ceremony. And they are sacrificing, and they are painting the women's heads with tar and ash as part of the grieving process. And in the back, you can see people singing. So this indicates to me that he was either in Nevada City when this was going on, or he was at Pudadon near the Yuba River. And this is a picture of a Indian fan mango. They were quite common throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s. People still got together. Here's a couple images of Indian girls making a bread of acorns, Yuba River, 1851. And look, the little girl is smiling, how did he get them to trust him? How did he get so close to these people? Here's a picture that was very faint. And then once digitized, we see this woman has the morning ashes on her head. And it isn't just random, plopped some ashes on someone's head. It was very artfully done. It was the line of the ash and the tar was brought underneath her cheek. And I think so that when she's cried, that there would be all the more black stuff dribbling down her downward face. And this is one of my favorites, this small child reaching up, hopefully, into the sky. And again, another never published before, Henry Brown. And it's very different from his other work. And we don't know where it is, but there is an American standing here and he is shielding a child. And this man is trying to moderate, this man is clearly quite angry. What's very curious is that this woman has a Sioux Indian hairdo. That this woman does not look like she is a local. She looks like she's one of the people who came in with the fur traders. Another woman and child. And this is an image done very early in time. And I think it, and the message, and it's usually been interpreted as how Indians assimilation into white society is inevitable that they were doomed, they had to assimilate or die. But I think there's another way to read this. I think it shows how quickly the Nisanon had to adapt or die. In weeks, months, years, they had to adapt their way of life. And that meant working for heading up work parties that worked for miners. This is not a brown, but it's a wonderful picture of a Indian chief with a beautiful headdress, a native headdress on the Stanislaus River, a Yuba River Indian gambling. This man is holding the little pegs behind his back and these people are trying to guess. And what this, we discover something the closer we look at that. And that is, this says Yuba River Indians gambling. So we know this was down at Smartsville Roses Bar area where Henry B. Brown was. But it turns out he did portraits of these same individuals. So we know they were on the Yuba River too. That they were Yuba River Indians. So this places a lot of different portraits in Nevada County and Yuba County. Now the clear supposition is that Brown must have been at the Fort Union Treaty of 1851 and that's how he happened to be able to see a lot of chiefs and a lot of people were gathered there. And that's how he got to do this. Well this is for those of you who are probably aware of this. 18 unratified treaties in California. The federal government had a policy and it was you have to buy Indians land before it can be distributed to white people. All right. So, or before white settlers can move in. So the federal government was a little late but 1851, they came in and they started negotiating treaties with the Indians. And one of the groups they negotiated with in this area called 2288 is the Nisanon or the Southern Miter. And what's going on here is their territory is being surrendered. They want them out of the Goldridge, Red Bridge territory. So and then they're going to agree to stay in this area right here. And same thing up at 290. This is all being surrendered so but the Indians are reserving this part in this reserve area as well. All right. And here's another rendition of this. And a lot of the richest gold area indeed was outside the treaty area. But look at this. It's bounded on the north by the Yuda River and the south by the Bear River which are full of gold. And also this is very rich. But here is Union Ranch where that treaty was negotiated. Right there. 1851. Another rendition of that. That treaty boundary. Now the senate did not ratify this. So this reservation did not occur. Here was one of the signatures. And what can we learn about these men from these images? Are there clues here? Now clearly the child, either a girl or a boy, is a member of the elite. But Wima has no ornamentation. He shows a a culturation and he has on a white man's clothes. He was the chief signator at that treaty. Here I think this looks a lot like him. Oh, I think this was his daughter possibly married to storms. Here's another signature to the 1851 treaty. Walupa. For whom the town Walupa is named. And there's two versions of this. And you're going, well where was this picture? Where was this drawn? Well can you see what's in the background here? The slope and the looks here in the background. It's the it's the setter views. This was done at at Smartsville at the Union Ranch. Clearly right there. Walupa is famous in Grass Valley history for this well-documented incident in which he, you know, Indians are basically surviving by the gold dust they're collecting. And the people are starving. So he goes to a shopkeeper and promises to bring back gold after they have a chance to gather some. And they did. 40 men brought in sacks of 100 to 150 weight in gold in the following year. Here's another signature to the Fort Union treaty. And again what's in the background? The setter views and then the upland there. So it's that it's that eco tone between these two places. And there's a couple pictures. But we know from here was one of those pictures of a portraits of a man who was in the the gambling picture. We know that Henry B Brown couldn't have been at the treaty. I think this Tacoma is this guy. There's a similarity in the facial stroke. [Applause] Do you have any questions? Yes. I'm curious. Well Mr. Proud, Clyde Proud, who is the descendant of Bullock, was very excited about it. And I did share these at a Nisenon event last year. Yeah they're they're aware. They're aware of it. This this publication goes in deeper to what happened at the Treaty of Fort Union. As you know, the Nisenon says our land was never ceded. The treaties were never ratified. And this article goes deeper into what happened there. And my theory is is that these particular Nisenon leaders were pretty sophisticated. They've been dealing with traders for some time. And they got the best of the negotiator and got an absolutely fabulous reservation that had gold on one side and gold on the other. And if you want to hear the sort of the nuanced story of what I what I think I've learned from what happened there at the Fort Union Treaty, please take a look at this. And I think the very fact that they got a fabulous reservation that had gold deposits on it, perhaps doomed all 18 treaties. Because they couldn't, it was such a good reservation, they couldn't ratify that treaty. There was a huge uproar and opposition to it in Nevada County. Penn Valley was located in the middle of it and that was valuable for grazing. And it's just, I think, Nevada Countians were very instrumental in getting the treaty rejected and the other 17 went on. Yeah. And before many gatherings in this area, the hosts will pay homage to the indigenous of the region. And I've heard some debate what in favor and out of favor of doing such a thing. I'd be curious to hear your perspective. I'm sorry, I didn't quite understand what you said. So when meetings are held, yes, the host will typically say offer homage to the indigenous. We are on Nisenon land. I'd like to hear your perspective on that. I've heard debates in favor and out of favor of doing such an homage. You know, I see, I've been doing Native American studies for 20, 30 years and I've seen this transition. I first started in New Zealand and Australia, Pacific Islanders. I just don't do it myself. I guess I'm just kind of an old school academic and I don't oppose it, but I just don't do it myself. But from Nisenon's perspective, do you, do you, can you enlighten us on the purpose of it? Oh, the purpose of it. I think it's pretty straightforward that this was indigenous land and we have to be aware of the people who were the first people here. Is it insulting to them? Oh no, no, no, no, no, no. Because I think Shelley and the, and the Rancheria people feel like this is unceded land, it's still theirs. You know, that's another reason to, to, you know, make this front and center in people's consciousness. And as many of the images, the sketched images show the complexion is being pretty light, yet we see photographs that are in fact very dark. What are your thoughts on that? Do you think that was purposely done by the artist? I think it depends on the time of the year. But, and I think this particular artist, can you say, or is it medium? Yeah. Have you found any journals from any of the men that were written around and traveled that might add some more inspiration? No, we've looked and looked and others have looked as well. And Tom Blackburn does a great job of kind of sorting out what happened and who he was and where he went and based on the available information. And what I did is I just further nuanced it a little bit by explaining how important Henry B. Brown was to Nevada County, specifically to the Nisarn people, because the Sacramento Valley pictures are just thought to be his very best. But I think some of these Nevada County and Nisarn pictures should get their recognition as well. Yeah. What brought Henry Brown here? Was he looking for gold like everybody else? No, no, no. He was kind of sickly. And I think he was about 35 years old, unmarried. We hardly know anything about him, but like many people, oh, he, he, one of his relatives was assigned to be the U. S. postmaster in San Francisco. So he came along with his, his relative for the adventure. And that's where he was based. So yeah, you said were there any journals? There was a little bit of family history and a few documents have come up. He gave a number of his pictures to his cousin for safekeeping. And then she put her name on it and said these are my drawings. And then that created all kinds of confusion for, for a while. So yeah, but there's just little tiny bits of information. But, but we're, you know, I think maybe more will be revealed. Many pictures were, didn't come to light until 1920 when they were given to Sea Heart, Miriam. Maybe other people have collections of Henry B. Brown pictures, you know, and, and they will donate them or they have letters or something. I mean, this is, it's possible. Do you know how long did he live after this? He, he, we think just till 1860. He died very young. He was at a consulate. There's some pictures showing that he ended up in a consulate in the Bahamas or something. He went home to Massachusetts once, but then, you know, he fades from sight. Now the pictures that were donated to Sea Heart, Miriam by an anonymous source, I think was the person or persons who were living with him when he died and inherited his stuff and hung on to it. Like a lot of us parents hang on to the very first drawings of our kids, those first little, you know, they treasured every single one of these pencil drawings and kept them and preserved them for a number of years and then anonymously donated them. And then they felt, they came into the, the bank rock and the Huntington. So, I mean, it's a miracle that they survived. [Audience member] Do you have any theories personally on how you think he obtains to intimate portraits and like scenes of losing his Well, I think he came to a, the morning ceremony. And these morning ceremonies were typically three or four day events. They were done at the time of salmon runs, so there was lots of food, lots of acorns being harvested. People are, are, are gambling, they're feasting, they're in a happy, relaxed food, and there's lots of people gathered together. And so I think that explains why. But, but how he got all these people to cooperate, I don't know. He must have been a very, very gentle soul. [Audience member] Do we know his training in Parkville at all? Did he sell thought or did he have any formal education? Not much, not much. Just scraps of information. Can I just get some books for sale? Yeah, there's some, I have some of these for sale for $30, and this is $15, and there's Nevada City Neeson on, which is a companion piece to this. So they're back in the corner if you're interested.

Zoom Out

Zoom In (Please allow time for high-res images to load)

Zoom: 100%