Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2023-04-20 - Traveling Photographers with Carl Mautz (56 minutes)

Nevada County Historical Society presents local author Carl Mautz who will be discussing his book titled “Biographies of Western Photographers – 2018 edition“. Traveling photography has long been recognized as a category for collecting 19th century photography, but who were the traveling photographers? Carl will touch first upon a photographer who visited Nevada County and then talk generally about the category of photographers who sought customers and provided services to the many who live away from urban centers. Presentation will include many historical photographs.

Author: Carl Mautz

Published: 2023-04-20

Original Held At:

Published: 2023-04-20

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

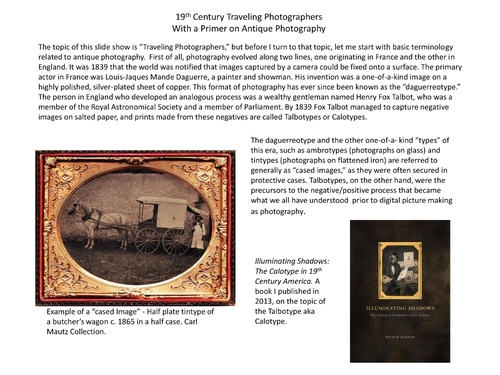

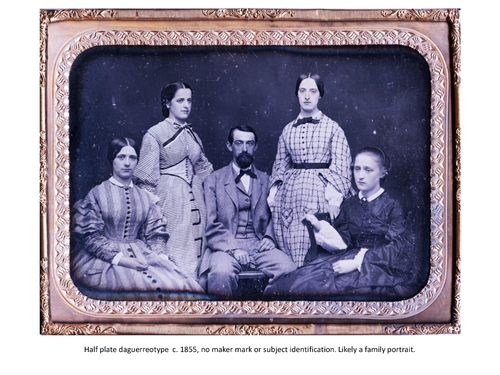

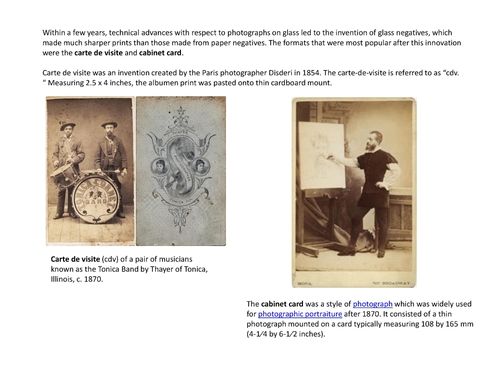

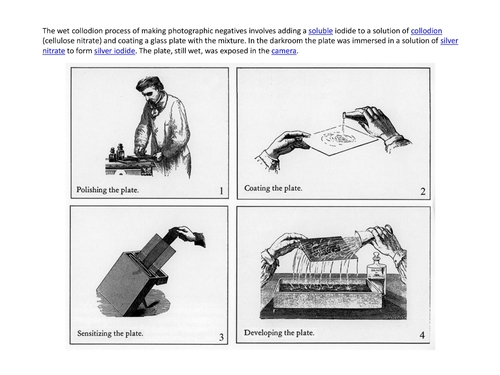

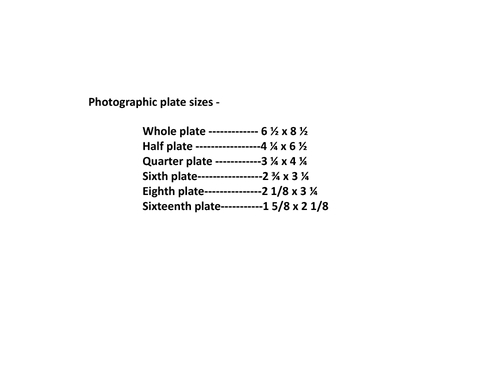

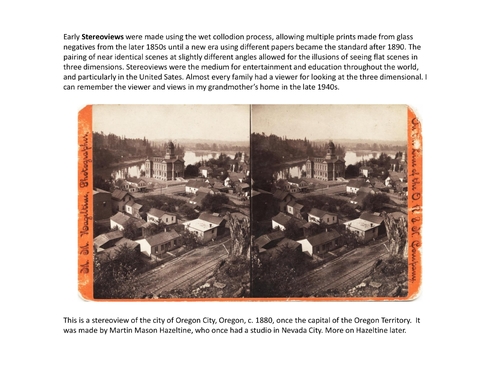

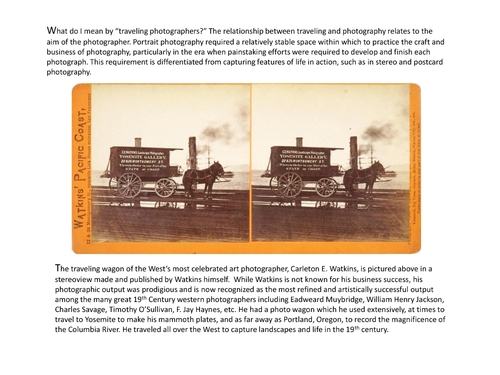

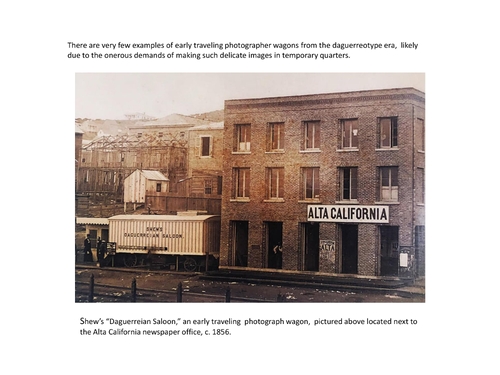

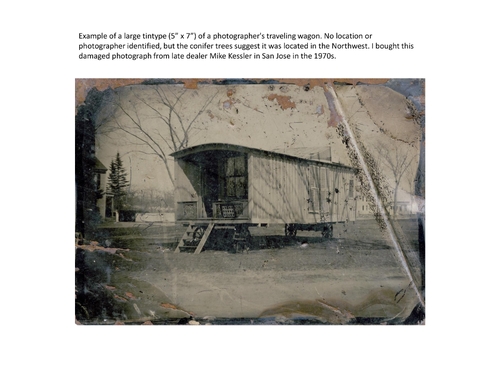

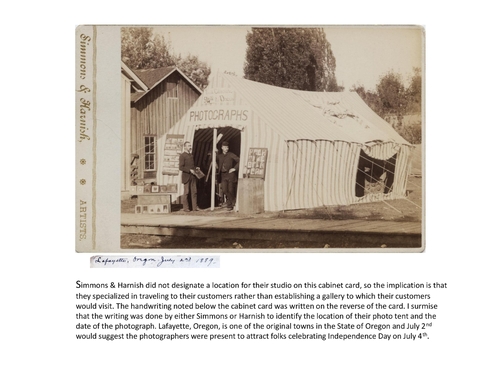

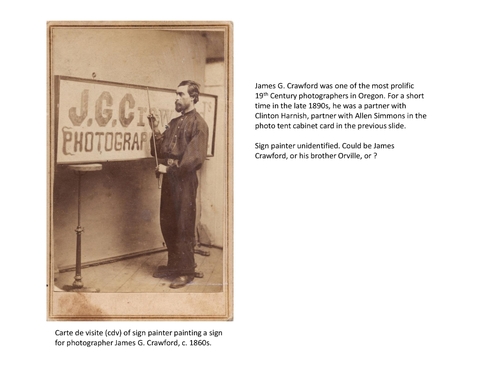

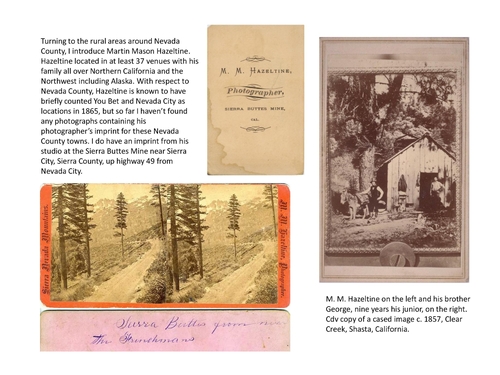

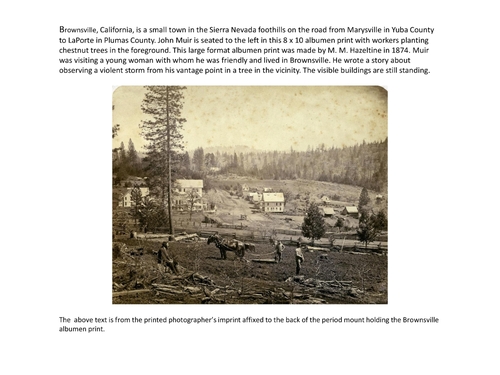

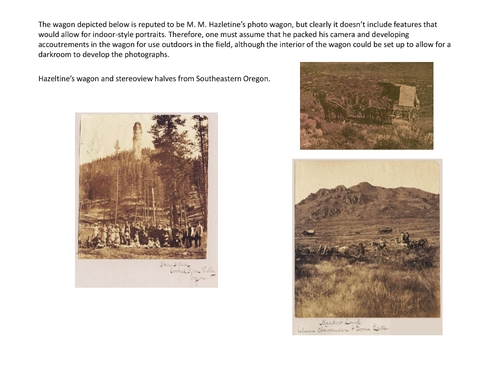

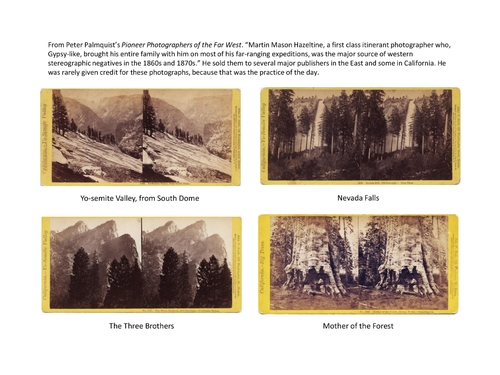

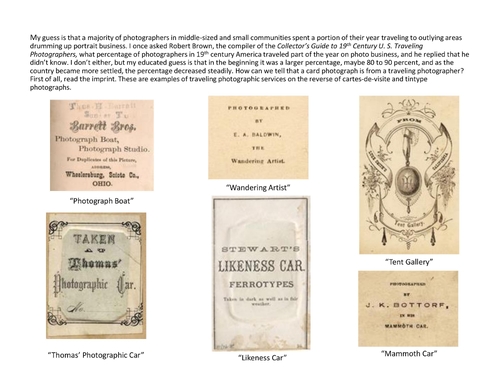

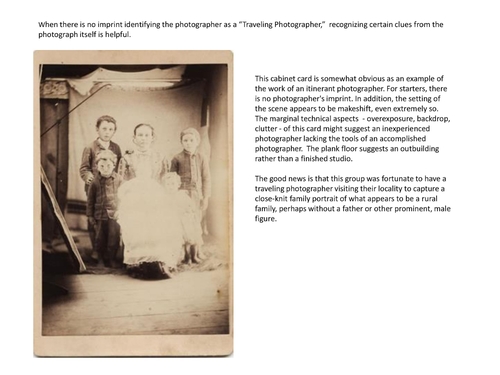

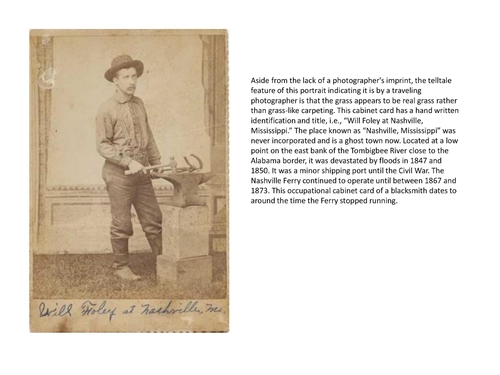

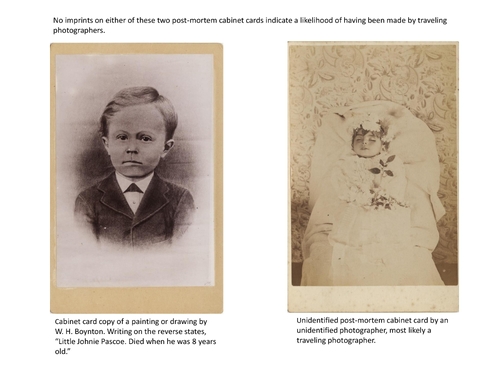

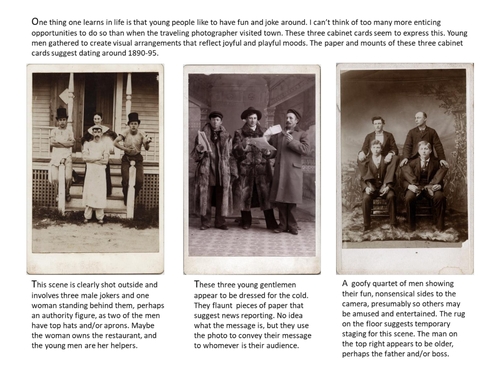

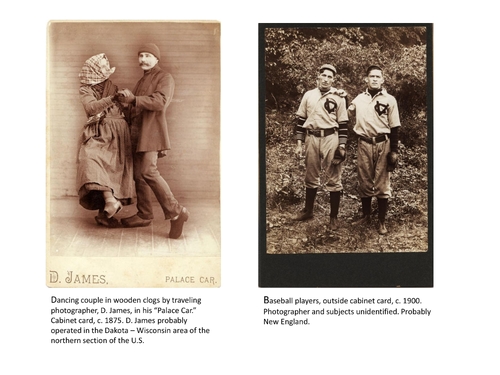

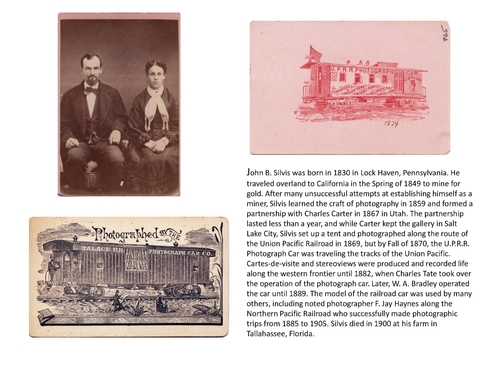

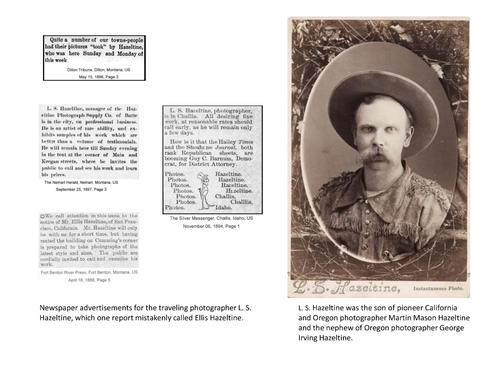

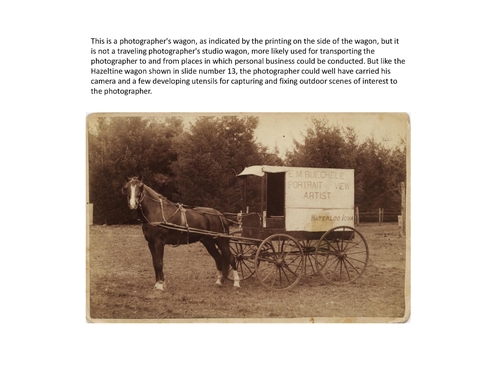

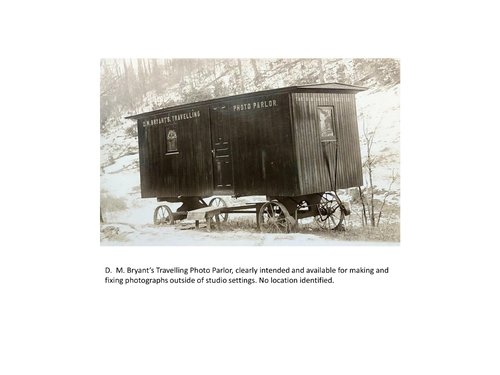

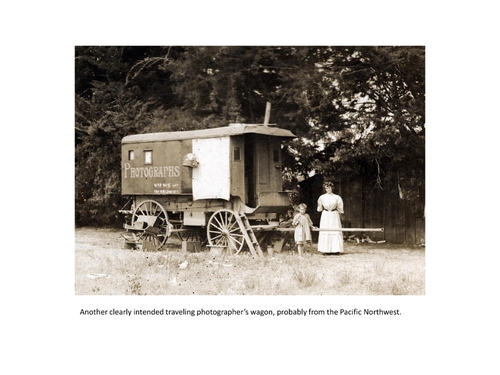

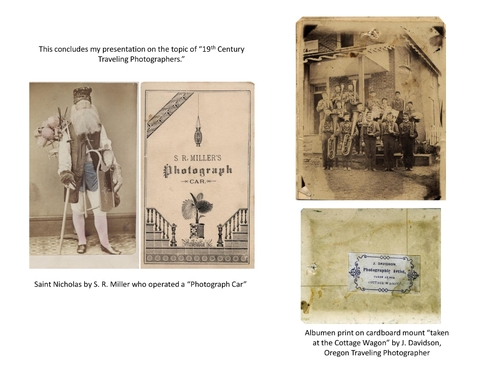

Okay, so tonight we have Karl Watts and I will tell you that Karl has been on our our speaker night list for at least five years I'm sure. So I probably reached out to him before we just never connected and I'm really glad we've done that. Finally, Abby here to share with us his rather outstanding book. It's a pre- imminent book on traveling photographers. So I'm hoping you can share with us what is a traveling photographer? You're on. That's a question. Well actually I did give a talk. There's a group of five years ago. The history of photography is a slight challenge. I must admit. But I guess it's funny though. Okay. [ Inaudible ] [ Inaudible ] No, he didn't know he was. . . So the subject, the topic that we're going to talk about is traveling photographers. We will address that question, what are traveling photographers? But there are a number of categories. But before I turn to that topic, let me start with basic terminology related to anti-photography. So some of the names all figured out here. First of all, photography of all along two lines. One originated in France and the other in England. It was 1839, January 1839, that the world was first notified that images captured by a camera could be thick off the surface. The primary actor in France was Louis-Jean-Mondet de Guerre, a painter and showman. His invention was a one-of-a-kind image of highly polished silver-plated sheet of copper. The format of photography has ever. . . This format of photography has ever since been known as the de Guerre text. And I have a nice example of it in my class case back here, which you can all look at later. First in England, who developed an analogous process, was a wealthy gentleman named Henry Fox Talbot, who was a member of the Royalist Astronomical Society and a member of the Parliament. By 1839, Fox Talbot managed to capture negative images on salt paper, and prints made from these natives are called calotypes. I don't have any examples of that style of photography. They're pretty scarce. Unfortunately, I made my living last number of years by installing photographs, so I sold them all. But I do public books as well, and let's see. I think it's really how I use it. Oh, I got it. I got it. So that's a book that I published on American teletypes, or talotypes. And it's the only book on this process. It was done by Americans. Using really wealthy Americans that were traveling in the Middle East and Europe. So that's about one thing I had to show about talotypes. So over here on the other side is what is called a half-plate kin type, a butcher's wagon, about 1865. So this is actually the daguerreotype that I brought. It's called a quarter-plate, I mean a half-plate. It's a very beautiful thing, as I say, look at it in the case behind me. It's about 1855. There's no major mark or subject identification. So there's a lovely family portrait. So technical advances with respect to photographs on glass, led to the invention of glass negatives, which made much sharper prints than those made from paper negatives. The formats that were most popular after this innovation were the carte de visie and the cavity carte. This one. It's a little tricky here. So this is a carte de visie, and this is a cavity carte. So the carte de visie is a 2. 5 by 4 inch card. It's an albumin print, based down on a cardstock, which measures 2. 5 by 4 inches. It's kind of my specialty, is carte de visie. So this one, being from my collection, I think it's really exceptional right here. So Black on the Wake Eye, we're part of a band, and then you talk about Illinois in 1870. So the next to the cabinet photograph is that one, and that's an artist drawing on his easel. And that's a cavity carte, which is measured 4. 5 by 6. 5 inches. And it was very widely used in portraiture after 1870. So the white collodion process of making photographic negatives involves, not everybody can do that. Anyway, it involves having a soluble iodide to a solution of collodion and coating a glass plate with the mixture. In the dark, when the plate was immersed in the solution of silver nitrate, it formed silver iodide. The plate, still wet, was exposed in the camera. So the first plate, the first illustration, you're polishing the plate. The second one, you're putting the three until the wet collodion process, because the solution's wet when it goes onto the plate. And then it is, so the plate is sensitized, and then it's exposed in the camera, and then it's developed in the plate, and then developed in the plate. And this is a very attaching kind of procedure, so not everybody can do it. So then, let me talk about photographic plate size. I mentioned that the gyrotype, that gyrotype is called a half plate, and that's actually a half plate, too. But they're both what are called quiche images, because they put them in cases, and the glass would keep the photograph from touching the protector, called the protector. You see that? The frame around the image has a protector underneath it, but it's above the glass, above the gyrotype, with the three sensibility. You're following all that, I hope. Anyway, you've got the whole plate, half plate, quarter plate, six plate, so forth. That's the way everything was measured back then in photography. Then, we have stereo views, which I'm sure many of you are familiar with. They were being developed during the same period. The early stereo views were made using the wet clothing process, which we just talked about. And they allowed multiple prints made from class negatives. From the later 1850s until a new era, using different papers, became the standard after 1890s. The pairing of near-identical scenes at a slightly different angle allowed the illusion of seeing flat scenes in three dimensions. Stereo views were the medium for entertainment and education throughout the world, and particularly in the United States. Almost every family had a viewer for looking at the three-dimensional images. I can remember personally, I'm now 80, and I remember in the late '40s, being in my grandmother's house, when she had a viewer in stereo views, and I looked at it back then. So then, they became very collectible waver. I didn't get any of her stereo views, but I had the experience. This is a stereo view of Oregon City, Oregon, around 1880. Oregon City was the capital of Oregon territory for a while. The photograph, this stereo view, was made by a guy named Martin Mason Hazeltide, who once had a studio in Nevada City, which I'll talk more about a little later. By the way, if anybody has any questions, ask away. What do I mean by traveling to Target? That was Dan's initial question. Portrait photography requires a relatively stable space within which to practice the craft and business of photography, particularly in the era when painstaking efforts were required to develop and finish each photograph. This requirement is differentiated from the capturing features of light and action, such as with stereo and post-partum photography. This gives you an example of traveling. This is a very famous traveling photographer's wagon. He's actually not a portrait photographer. This is Carlson Watson's wagon. Carlson Watson is probably figures to be the most. . . He's not known for his business success, but he's. . . Well, he's a pretty. His photographic output was prodigious and is now recognized as the most refined and artistically successful outfit among the many great nanki-tendrick photographers, such as Edward Mydred, William Henry Jackson, Charles Savage, Jothio Sullivan, and so forth. He had a photo way in which he used extensively at times to travel to Yosemite to make magnificent mammoth blades. And as far away as Portland, Oregon, three-quarters of the magnificence of the Columbia River, he traveled all over the west to capture the landscape of Dunlighter in the 19th century. But we're talking more about. . . In traveling photographers in this context are photographers who want to make a business out of taking portraits of people. So in the early days, nearly everybody was a traveling photographer. A few, I guess, who would afford to have a studio in a town, but most of them had to get out there and find customers. So that's what we call, what I call, traveling photographers. And here we have. . . This is right here is a little newspaper ad. This is M. M. Hazeltine's son, L. S. , and this is an example of a traveling photo wagging. And there's no indication as to who this guy is or where it was at, but it's a beautiful example. And actually I brought it back in the case. You can look at it. There are very few examples of traveling photographer wagons. There's a type of radio, but one is shown here. It's William Shoe's. He called it the "Gurion Saloon. " So he could hatch up his horses to the Gurion Saloon, ride out to such-and-such place, and get customers in there to take their gear types. So it's in the 19th of '56. And the Alta California newspaper is right nearby there. There it is. So this next image is the 5x7 tin type. It doesn't quite fit into the neat case, half-blade, full-blade, and each designation. But as photographers, traveling away is in terrible, terrible condition. I applied it back in the 1970s from a dealer in San Jose. And the trees, I guess it was northwest, because it had all the concert trees here. And I actually went to the trouble of cleaning it up digitally, just so I could see what it looked like restored. Thank you, here. How is it restored, okay? Okay, this next image, this was found by a dealer in Portland who I had known for decades. Well, I'm from Portland, that's why I know that. But anyway, I've been lucky enough to tap into this and put it on eBay, and I got to test directly with him. It's a fabulous artifact. So this is an example of a studio. So it's got two photographers here, Simmons and Marnage. And they're labeled as artists. There's no address, so it's not like they're not advertising a studio. And one of them did right on the back, Lafayette, Oregon, July 2, 1889. Well, Lafayette, by the way, was one of the original towns in Oregon. It was incorporated in the 1830s. And then July 2 would suggest that they're there for July 4 celebrations. You know, buying tessellers. So here you have, this is the, see if here's the skylight, put the light in, and here too. And then over here you have examples of the photographs. Up here is a sign that says, "Four dozen cabinets. " A dozen cabinets for 50 cents, I think. Anyway, it's just an amazing cabin card. It just provides all kinds of information for microspaces. With 50 cents, it's very expensive. What would 50 cents have been? 50 bucks. Got an end. Still more than each, the number of furniture in this place. How about that? Thank you, number 50 cents for the dinner. We're ready. Thank you. Nobody knows. So the next slide, I just have this in here because I love this part of the Z. This is the CDB of James Crawford. It shows James G. Crawford. So this is a guy's painting design for James G. Crawford, who was a prolific 19th century star and anoreist. For a short time, in the late '90s, he was a partner with Trenton Harnish, who was the partner of Alan Simmons, going to be a photo tent cabin here we just looked at. The sign painter is unidentified. It could be James Crawford, or it could be his brother Orville. Or it could be Harnish, or it could be Simmons. Anyways, kind of what I'd like to look at is these carton zines. Okay, the next slide, which I'm going to turn to, is a very interesting piece of art. Any questions? No? Okay. So here we go. We get to Martin Mason Heasle's art. So he was actually an incredible photographer. And he worked in Yosemite for many years in the 1860s. So he competed with Carl Watt because of people like that. He was a really good photographer. In those days, business sense was a little different. So, Heatland's eye would sell his negatives to Eastern and San Francisco publishers who would publish something. They wouldn't give him credit. But he didn't care because it just wasn't a practice back then. And so there's a lot of, which I'll show you soon, I'll just go down here in the past. Those are all published by John Soolay in Boston. And they're all from natives that handle time checks. They're beautiful, beautiful images. Okay, so the stereo view, what's that? Question. Who would be the customers for these carte de bistes in the catalog? Were they like a postcard on their day? Well, the customers would be the sitters. They had their photograph taken for their family and their friends. Like during the Civil War, it became very widespread to get your carte de bizit taken. During the Civil War, it became just exploded in popularity. And they would make Victorian albums, leather albums, and they'd have little slots, and you'd put your friends in there, you'd put Lincoln in there, and maybe Tom Thumb, and relatives, maybe Custer, when he became famous for dying. He was famous for that. So, generally, that's the end of the time photographer is the port photographer went out into the field applying test scores. And he had a big family, and he drove them around. He was an itinerant photographer. He drove all over the place in Northern California and Oregon and Washington and Idaho, Montana, but mostly in Northern California and Oregon. And he did a lot of work. And his brother, George Irby, he was nine years younger. And I'll show you. This is an amazing carte de cibie. But it's not a cbb per se. It's actually a photograph of a photograph. So this is the part of a cb image, probably an ambrotype. But it's got a protector around it. It keeps the glass off the photo itself. And the guy, so he'll tell you, it's pinned on a board. See, that's a screw, and it's pinned against the board. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. He had two addresses he advertised during 1865. One in U-Vet. And one in Nevada City. I haven't found any photographs with a hill-times infra indicating these locations. But I didn't do that before on the Sierra Bew's mine. Which you can see right there. All right. And that's a -- it's a portrait. This is an ordinary portrait. Okay, now this is a really -- this is a really -- to me -- a very interesting photograph. So -- and I'll leave my photograph here. Let me do this. A shovel of paper. So I don't know how many of you know where Brownsville is. It's on the road between Marysville and the port. And it was an old bull road town. And many of us, I guess, back in the day. It's also where I had a law office there for ten years. And I can tell you that this -- these buildings are still there. One was a restaurant called Lottie Bremen's. And the other one was a bed and breakfast. My friend Nancy All-Brown and Russ Street was an antique store that Rex Maudsley, a friend of mine, has owned. Anyway, 18 -- whoops. In 1874, John Muir, who -- maybe he liked -- lived in Brownsville. He was a visitor. And there was a big storm there. He -- he had a -- he had an interesting character. He decided to climb a tree and watch the storm from the tree. Well, here. So anyway, that is -- let me think, John Muir right there in this rock code. And the guys over here, they're planting chess entries. So the chess that grow was planted right there. And the chess entries are still there. Those are the 8 by 10 albumin print on a period mount with a deal sign's paper label on the back. Fabulous thing. But anyway, I bought it and then I sold it. So I kept just getting it. Doable thing. So this is not very sharp. It's a photograph from the distance of a wagon. And we think it's a needle-dudged wagon. And anyway, these are stereo paths. What they did back in those days is the photographer would use the -- cut the stereos in half and make a presentation album to show what they did, what they had. He doubled their mileage with getting two photographs out of one. So anyway, they did that a lot, but -- look. Where'd he go? There. So these are from Oregon, the Crookard River in eastern Oregon. And we think those are both by Healdine. Okay, now going back to this piece. These are the stereo views that Healdine made of Yosemite. And they're very, very popular. And they sold well. There were a number of publishers that published them. Later he did his own stereo views. And they're kind of -- they're very nice. But anyway, this was a big deal, I think. And later he lived in the Mendocino. And he published a lot of the stereo views of the Mendocino logging operations in Little River, Big River, that whole area around Mendocino. And Sousaix in Boston published them. So I used to find them for my friend, Glenn Mason, who grew up in Mendocino and went to Arcadia. And he collects them. So I used to sell them to him. Okay. Now these are all samples of what we call imprints. So the photography imprint is basically his logo, his way of advertising who he is and where he's at, so on and so forth. So we've got different -- So you've got the photograph boat. You've got Thomas X's photographic car, wandering artist, likeness car, mammoth car, tent gallery. What's a ferrotype? Ferrotype is a tent type. Ferro is iron. So tent type is Latin iron. So along with the dendrotype, the emertype on glass, the ferrotype or tent type on Latin iron. So this next cabinet card is really interesting. I don't know if anyone wants to see it, I guess. Because it really tells you what you look for to figure out if it's a traveling photographer. So the first thing you notice is there is no imprint. So whoever is taking this photograph wasn't really that interested in advertising for more business. He just wanted to get the job done and get paid and move on. So there's no imprint, which suggests a 19-year-old photograph photographer. In addition, the setting of the scene appears to be makeshift, even extremely so. The marginal technical aspects such as overexposure, backdrop, clutter, and so forth suggest an inexperienced photographer, lacking tools of an accomplished photographer, which you find in town and the city. The plank floor suggests an outbuilding rather than a finished studio. The good news is that this group was fortunate to have a traveling photographer visiting their locality to capture its close-knit family portrait of what appears to be a rural family, perhaps without thought or prominent male figure. So I think this is really important. I mean, this isn't something that the market would recognize per se, but I love it. I think it's a great example of the history of the traveling photographers. And here's another one. This is. . . So this guy is. . . This guy is Will Foley at. . . Where is he at? Anyway, it's in Mississippi. Yeah, he's got it in Nashville, Mississippi, which I never heard of. He's obviously. . . This is called "Occupational. " It shows something with his tools. So I looked up Nashville, Mississippi, and the place was never incorporated. It's a ghost town now. It's located at a low point on the east bank of the Tom Bigby River, close to the Alabama border. It was devastated by floods in 1847 and 1850. It was a minor shipping port until the Civil War. It almost very continued to operate until between 1867 and 1873. This occupational cabin guard, a blacksmith, dates to around the time the dirty stuff runs. So it's pretty routine. So. . . Okay, these next two cabin guards. . . Whoop. Got the same one. They're both unidentified. They're doing print, so the farmer didn't care to advertise. So he just got doing his job, playing a It was a way for people to get the likeness of their loved ones who had departed. And now they're pretty able to collect it. So the one on the left is of a painting or drawing by a man named W. H. Boynton. Could be a woman, actually. I don't know. And on the right in the back says, "Little Johnny Pascoe died when he was eight years old. " So this is a copy photograph of this drawing or painting, and it's based on the cabin guard mount. And there's no indication of the photographer, so it's very likely to be a traveling photographer. The one on the right has no idea if you're finding words about the photographer or the subject, but it's a baby who's died. So that's another traveling photographer. Likely many. So the next group. . . One of my favorites. So one thing that someone learns in life is that young people like to have fun and joke around. I can't think of too many more enticing opportunities to do so than when the traveling photographer visits town. These three cabin cards seem to express this. Young men gathered to create visual arrangements that reflect joyful and playful moods. The paper and mounts of these three cabin cards are just being around 1890 to '95. So the one on the left, you've got four people, three of whom are male, two of your males. Two guys have top hats and aprons on, and the guy that was an apron. There's a woman in the back. She might be the owner of the restaurant or the cook, but they're just enjoying having their photo taken, which I'll share with their friends. And then the one in the middle, these three young gentlemen, if they're to be dressed or they're real cold, they flaunt pieces of paper that suggest news reporting, no idea what their message is, but they use the photo to convey their message to whomever is their audience. The third photograph is a goofy, corrugated man showing their fun, nonsensical sides to the camera, presumably so others may be amused and entertained. The rug on the floor suggests temporary staging for this scene. The man on the top right appears to be older, perhaps the father or the boss. So now we have two more cabin cards. So the one on the left is one of my favorite pretty favorites, and it's a dancing couple with wooden shoes by a traveling photographer, B. James, where in this case we got the tip off that he was the traveling photographer. He called his Operation Palace Car. And you can see it's probably a bug star on the railroad, and it's probably in the northern U. S. , probably. They're probably Dutch or German, and probably the Dakotas of Wisconsin area. I love that photograph. How long did that take you to expose her up a little bit so I'm flirting? Well, one reason they didn't smile is because exposure took a while. And this is probably the 1870s, so it probably took a while, but he captured this pretty damn well. That's the part of my English. And they obviously like each other. I really love this photograph. She had the baby and the aunt on, and they're obviously dressed for the cold. And they have the wooden shoes on. And then the galley garden next to it are a couple of baseball players. So there's no, again, there's no photographer's imprint, and they're outdoors. So it's a couple of ballplayers and probably a tiny, a tenor of stars, I think it is anyway. So, that's that. So we're getting here, I'm getting in here. So this is, so John Silva, John B. Silva was born in 1830 in Lockhaven, Pennsylvania. He traveled overland into California in the spring of 1849 to mine for gold. After many unsuccessful attempts at establishing him, Silva as a miner, Silva's learned the graph of photography in 1859 and formed a partnership with Charles Carden in my last compilation of Western photographers. It was a little essay on Carden by one of his relatives. Anyway, Silva's left and Carden kept the thing going in a solid city, kept the studio going in a solid city, whereas Silva's had this car made for the Union Pacific Railroad. So he would ride the tracks all over northern U. S. taking photographs. And you hired yourself out as a portrait star. So these are just, these are customers of his. A couple we've got the photograph taken. But this is the back of the courtesy in their traveling railroad photograph I gave you. So next we have, so these are some examples of newspaper ads in papers advertising the services of Leland Stanford Hazeltine, who is M. M. Hazeltine's son. I want to find out what the relationship was between Leland Stanford and Governor Stanford and Hazeltine. And so that's the topic I'm interested in. But anyway, he ended up in, he was up in Idaho, I think he did this. He also includes in Montana a lot and he ended up down in the Mendocino, which is a fuck word, he was a boy. And he was like, he took a lot of photographs of the shipping down there. So this is a different kind of wagon. It's also a photographer's wagon, but as you can see it's not big enough to set people and take their photographs. But you can carry around all the equipment and the chemicals and so forth that you would need to get their, get their glass negatives and take their pictures. So that's what this particular image is of a photographer in his wagon. So the next one is where we're traveling photo parlor, he calls it. This is Bryant's traveling photo parlor. I think that was used to have, shoot the photographs, but I don't really see a skylight there, but it's not the only thing at the angle. But there's no location identified, but it's great to, pretty exciting to own the wagon. Question. Pardon me? Question over here. In these photo wagons, what typically would, I mean were they partitioned off with part of the dark room and part of the studio for sitting? I think all kinds of different ways. And I think that, yeah, a really well-adclinic one, a really well-designed one, would have, that we have that kind of arrangement, you know, where you fish up and make it better than you do business. But I'm sure there's all kinds of permutations. If they know who the photographer was, how could they remember the song, the hammer, their brother and so forth. Well, you have one, right, you said? I do have one. So what's your selecting site? Well, it's an animal. I have one that has photographs of it. Oh. Yeah. Like the one I showed earlier, it's actually in the case back here, if you can look at it. So anyway, so this is probably in the particular north, whoop, in the previous one, right there. Somebody decented this to do me out of the blue. It's really neat, you know, maybe a little later, maybe a little 1890s. But obviously the family travels around in this thing, and they unload and set up, and they get customers and take their pictures. So this is an example of a photographer's wedding, his wedding child. And he's probably taking the picture. I think this is a chorus. Of course, yeah. So this is sort of the end of the talk. I love this. This is a Carte de la Zie, and a photograph car. This guy has decos, Saint Nick, and I'll tell you that's cool. And the other one is like Oregon, so I kind of had a lot of Oregon stuff. So this is the cottage car, and we're taking the picture of the van here. So it's kind of cool. That's it. The legends look so ungainly. How did they ever get them up and over origins? I don't know. It's hard to imagine. They were pretty resourceful people. I'm sure we had all of us, or many of us, had relatives back in those days that could do this sort of thing. A lot of work. Oh, yeah. More questions? Can you buy pictures from people? I guess a lot of us have a lot of pictures. Me too. Yeah, I bought a picture. Not like I used to. I get more slow. I can tell you about this. Anybody else? Come on, buy Paretta. Were all these pictures we saw tonight in your photographs, in your collection? No, some were from other people. And some I have sold, or I have a scan. So all these photographs are in the public domain. I used to study copyright law a little bit. Making mountains, writing spit, spit out the copyright thing, as much as you can, of course. All about money. But back in the 1860s, the 70s, the 80s, these were all over the land. You got the picture, you can just take off. What's the oldest picture you have? That I have now? Well, the daguerreotype is 1850s. I've had older daguerreotypes. The daguerreotype was announced in January of 1839. So in America, Samuel B. F. B. Morse, who went back to Paris, when this announcement was made, and he brought a daguerreotype apparatus with him home to the U. S. And he taught people on these coasts how to make daguerreotypes. So that was the beginning of daguerreotypes, the photography of the daguerreotype. The Americans are very resourceful, and they want to do the daguerreotype. They make some beautiful, beautiful work back in those days. So you can see this one back here, and get a chance. It's a really beautiful thing. I've seen so many people behind. What life did they use? You said 1860, 1870. They didn't have electricity. You got the sun. They were in this way then. That's where they have the skylight. Wow. I know. I remember. I do too. And people had to stay very still. Is that correct? See here? Yeah. The skylight? Yeah, they had the same very still. And here. Whoop. The skylight up here? It was that portion of the roof that opened up. And then you have in the tent, they have the light into here and here. Now, life is very important. I was just going to make a comment. I studied photography at the degree in photojournalism. And I really, I mean, to me, I don't think that they just only photograph in their wagon. I'm sure they probably did on site, people's homes, out in nature. So they weren't restricted just to the wagon. But that was their means of getting around. And if they could use the wagon to take photographs and have a bike, then they would do that. In an outbuilding farm or somewhere? Yeah. And like I mentioned, so this has the starper's information on the side, but they obviously didn't take photographs in it. Right. They would set up their equipment wherever they could bamboozle the customer alone, use their facility. When did the Garatykes and Timmy types go out of fashion? Good question. So the Garatykes, as I said, started in 1839. Actually, the first photograph was 1826. The Garatykes' partner, Gany Neeps, made that a computer. Anyway, the Garatykes started in 1839, and they just got it really popular, really fast, and spread it around, and a lot of them were made. But when the Frederick Archer in 1851 developed the glass negative. And so the glass, so the photograph on glass is called the ambrotype. It was also kept in a, where'd it go? Well, it's over there. That's a half-blade tintype. So anyway, with the technological advances with glass, it made much sharper photographs. Well, it didn't make sharper photographs. These are pretty amazing photographs of the Garatykes. But they don't reflect like the mirror, because they're like mirrors. So, you know, there I am, but I want the photograph. So that's kind of the ambrotypes that pushed the Garatykes out by, I'd say the mid-50s, or the late-50s, certainly. In England, they made them for a long time, and like as tourist things, they made them into the 1860s and '70s, the ambrotypes. But anyway, the tintypes came in right at the end of the 1850s, and the Civil War. I mean, tintypes take off as they did carton de jis, because they were smaller, people could afford them in the Civil War, or they won a picture of their brother or their father or their neighbor or whatever. So that was a big deal. And so that really spread the photography practice out there in the world. Were there many women photographers? That's a good topic. There were some great women photographers, but of course they were always my husband, you know, but there's some good ones out there. Yeah, there's some studies on women photographers, some good studies, actually. Do you have any Margaret Cameron Mitchell photographs? The camera? Margaret? I know. Because she was an early photographer. In England? Right. And she did large format stuff, and her photographs are very valuable. But I don't have any. I have one more question. When Edward Mybridge was the study for Stanford on motion, and then later on they developed a film, the callback process, what was that? Mybridge's work with Stanford was in the early 1870s. And then later on he went to-- And then he went back to Pennsylvania and worked for the University of Pennsylvania. And then for his time did it transition to some class or film? Mybridge was always working with class, negative. What was the process? He never went to film. I don't think so. No, film didn't come in total, like 18, late 80s, early 90s. And so by the turn of the century film was taking over. There's still some specialists that do it, even now, that do the old processes. I have a book called The History of the Woodbury Type, which I published for a guy down in L. A. He's Barrett Oliver. And he makes woodbury types, and he can do all the processes. So he can make amber types, or woodcullodians, natives, and friends that go through. Are the chemicals dangerous? Yeah. [LAUGHTER] A few exploding weapons. Well fired. And people would die of mercury poisoning? Maybe mercury to develop some of these processes. And if you smell of mercury then you'd go crazy or-- Good question. Could providers have a short life expectancy because of that? I think they did, actually. They did. How prolific were photographers on the East Coast? What's that? How prolific were traveling photographers on the East Coast? I didn't catch it. East Coast. The East Coast. Yeah, what about the East Coast? How many more-- [LAUGHTER] All these pictures are showing, looks like, all out in the West. Well, I'm the Western guy, you know, so-- In the East. [LAUGHTER] Pretend you're from the East. Were they prolific there? Oh, yeah. As much as the West? I can't understand what you're saying. Were they more prolific than the West? They probably had more-- No, they're all-- As the time went on and more and more people gathered in town, became more urbanized, then the traveling photographers were less and less needed to go out and get photographs. So they developed elaborate studios in all big towns, you know, like-- In Cincinnati, as a black photographer, that's pretty popular, who took a lot of great photographs back in the-- the yard type era, and then he went on from there, and he ended up in Montana and then finally see out. So, yeah, I mean, you know, it all evolved along the same lines. They were in communication. There were magazines being printed that alone took-- There were examples of people like Peter Britt of Jacksonville, Oregon. He was published in the magazines back in those days, and they all kind of kept pace with the new developments, and some were really into it, you know. They loved the new techniques, and they would get into it, they would buy the latest chemicals or learn the new techniques and so forth. So, anyway. They didn't all go for the new stuff. That's right. I have a lot of collection of a photographer by the name of Moore from Nevada City. He apparently never gave up the glass plate. I've got pictures of women in 1920s and 30s clothes on glass plates. Sure. Moore doesn't get careful for it? Yeah, that's true. Some people don't like to change. Well, black people didn't want a computer. [laughter] Mike doesn't dance a lot and he's using glass plates and some of the assembled stuff. Okay. So, how many folks think in about 20, 100 years, we'll be talking about how we transition from film to digital cameras. [laughter] Well, thank you. Thank you. [applause]

Okay, so tonight we have Karl Watts and I will tell you that Karl has been on our our speaker night list for at least five years I'm sure. So I probably reached out to him before we just never connected and I'm really glad we've done that. Finally, Abby here to share with us his rather outstanding book. It's a pre- imminent book on traveling photographers. So I'm hoping you can share with us what is a traveling photographer? You're on. That's a question. Well actually I did give a talk. There's a group of five years ago. The history of photography is a slight challenge. I must admit. But I guess it's funny though. Okay. [ Inaudible ] [ Inaudible ] No, he didn't know he was. . . So the subject, the topic that we're going to talk about is traveling photographers. We will address that question, what are traveling photographers? But there are a number of categories. But before I turn to that topic, let me start with basic terminology related to anti-photography. So some of the names all figured out here. First of all, photography of all along two lines. One originated in France and the other in England. It was 1839, January 1839, that the world was first notified that images captured by a camera could be thick off the surface. The primary actor in France was Louis-Jean-Mondet de Guerre, a painter and showman. His invention was a one-of-a-kind image of highly polished silver-plated sheet of copper. The format of photography has ever. . . This format of photography has ever since been known as the de Guerre text. And I have a nice example of it in my class case back here, which you can all look at later. First in England, who developed an analogous process, was a wealthy gentleman named Henry Fox Talbot, who was a member of the Royalist Astronomical Society and a member of the Parliament. By 1839, Fox Talbot managed to capture negative images on salt paper, and prints made from these natives are called calotypes. I don't have any examples of that style of photography. They're pretty scarce. Unfortunately, I made my living last number of years by installing photographs, so I sold them all. But I do public books as well, and let's see. I think it's really how I use it. Oh, I got it. I got it. So that's a book that I published on American teletypes, or talotypes. And it's the only book on this process. It was done by Americans. Using really wealthy Americans that were traveling in the Middle East and Europe. So that's about one thing I had to show about talotypes. So over here on the other side is what is called a half-plate kin type, a butcher's wagon, about 1865. So this is actually the daguerreotype that I brought. It's called a quarter-plate, I mean a half-plate. It's a very beautiful thing, as I say, look at it in the case behind me. It's about 1855. There's no major mark or subject identification. So there's a lovely family portrait. So technical advances with respect to photographs on glass, led to the invention of glass negatives, which made much sharper prints than those made from paper negatives. The formats that were most popular after this innovation were the carte de visie and the cavity carte. This one. It's a little tricky here. So this is a carte de visie, and this is a cavity carte. So the carte de visie is a 2. 5 by 4 inch card. It's an albumin print, based down on a cardstock, which measures 2. 5 by 4 inches. It's kind of my specialty, is carte de visie. So this one, being from my collection, I think it's really exceptional right here. So Black on the Wake Eye, we're part of a band, and then you talk about Illinois in 1870. So the next to the cabinet photograph is that one, and that's an artist drawing on his easel. And that's a cavity carte, which is measured 4. 5 by 6. 5 inches. And it was very widely used in portraiture after 1870. So the white collodion process of making photographic negatives involves, not everybody can do that. Anyway, it involves having a soluble iodide to a solution of collodion and coating a glass plate with the mixture. In the dark, when the plate was immersed in the solution of silver nitrate, it formed silver iodide. The plate, still wet, was exposed in the camera. So the first plate, the first illustration, you're polishing the plate. The second one, you're putting the three until the wet collodion process, because the solution's wet when it goes onto the plate. And then it is, so the plate is sensitized, and then it's exposed in the camera, and then it's developed in the plate, and then developed in the plate. And this is a very attaching kind of procedure, so not everybody can do it. So then, let me talk about photographic plate size. I mentioned that the gyrotype, that gyrotype is called a half plate, and that's actually a half plate, too. But they're both what are called quiche images, because they put them in cases, and the glass would keep the photograph from touching the protector, called the protector. You see that? The frame around the image has a protector underneath it, but it's above the glass, above the gyrotype, with the three sensibility. You're following all that, I hope. Anyway, you've got the whole plate, half plate, quarter plate, six plate, so forth. That's the way everything was measured back then in photography. Then, we have stereo views, which I'm sure many of you are familiar with. They were being developed during the same period. The early stereo views were made using the wet clothing process, which we just talked about. And they allowed multiple prints made from class negatives. From the later 1850s until a new era, using different papers, became the standard after 1890s. The pairing of near-identical scenes at a slightly different angle allowed the illusion of seeing flat scenes in three dimensions. Stereo views were the medium for entertainment and education throughout the world, and particularly in the United States. Almost every family had a viewer for looking at the three-dimensional images. I can remember personally, I'm now 80, and I remember in the late '40s, being in my grandmother's house, when she had a viewer in stereo views, and I looked at it back then. So then, they became very collectible waver. I didn't get any of her stereo views, but I had the experience. This is a stereo view of Oregon City, Oregon, around 1880. Oregon City was the capital of Oregon territory for a while. The photograph, this stereo view, was made by a guy named Martin Mason Hazeltide, who once had a studio in Nevada City, which I'll talk more about a little later. By the way, if anybody has any questions, ask away. What do I mean by traveling to Target? That was Dan's initial question. Portrait photography requires a relatively stable space within which to practice the craft and business of photography, particularly in the era when painstaking efforts were required to develop and finish each photograph. This requirement is differentiated from the capturing features of light and action, such as with stereo and post-partum photography. This gives you an example of traveling. This is a very famous traveling photographer's wagon. He's actually not a portrait photographer. This is Carlson Watson's wagon. Carlson Watson is probably figures to be the most. . . He's not known for his business success, but he's. . . Well, he's a pretty. His photographic output was prodigious and is now recognized as the most refined and artistically successful outfit among the many great nanki-tendrick photographers, such as Edward Mydred, William Henry Jackson, Charles Savage, Jothio Sullivan, and so forth. He had a photo way in which he used extensively at times to travel to Yosemite to make magnificent mammoth blades. And as far away as Portland, Oregon, three-quarters of the magnificence of the Columbia River, he traveled all over the west to capture the landscape of Dunlighter in the 19th century. But we're talking more about. . . In traveling photographers in this context are photographers who want to make a business out of taking portraits of people. So in the early days, nearly everybody was a traveling photographer. A few, I guess, who would afford to have a studio in a town, but most of them had to get out there and find customers. So that's what we call, what I call, traveling photographers. And here we have. . . This is right here is a little newspaper ad. This is M. M. Hazeltine's son, L. S. , and this is an example of a traveling photo wagging. And there's no indication as to who this guy is or where it was at, but it's a beautiful example. And actually I brought it back in the case. You can look at it. There are very few examples of traveling photographer wagons. There's a type of radio, but one is shown here. It's William Shoe's. He called it the "Gurion Saloon. " So he could hatch up his horses to the Gurion Saloon, ride out to such-and-such place, and get customers in there to take their gear types. So it's in the 19th of '56. And the Alta California newspaper is right nearby there. There it is. So this next image is the 5x7 tin type. It doesn't quite fit into the neat case, half-blade, full-blade, and each designation. But as photographers, traveling away is in terrible, terrible condition. I applied it back in the 1970s from a dealer in San Jose. And the trees, I guess it was northwest, because it had all the concert trees here. And I actually went to the trouble of cleaning it up digitally, just so I could see what it looked like restored. Thank you, here. How is it restored, okay? Okay, this next image, this was found by a dealer in Portland who I had known for decades. Well, I'm from Portland, that's why I know that. But anyway, I've been lucky enough to tap into this and put it on eBay, and I got to test directly with him. It's a fabulous artifact. So this is an example of a studio. So it's got two photographers here, Simmons and Marnage. And they're labeled as artists. There's no address, so it's not like they're not advertising a studio. And one of them did right on the back, Lafayette, Oregon, July 2, 1889. Well, Lafayette, by the way, was one of the original towns in Oregon. It was incorporated in the 1830s. And then July 2 would suggest that they're there for July 4 celebrations. You know, buying tessellers. So here you have, this is the, see if here's the skylight, put the light in, and here too. And then over here you have examples of the photographs. Up here is a sign that says, "Four dozen cabinets. " A dozen cabinets for 50 cents, I think. Anyway, it's just an amazing cabin card. It just provides all kinds of information for microspaces. With 50 cents, it's very expensive. What would 50 cents have been? 50 bucks. Got an end. Still more than each, the number of furniture in this place. How about that? Thank you, number 50 cents for the dinner. We're ready. Thank you. Nobody knows. So the next slide, I just have this in here because I love this part of the Z. This is the CDB of James Crawford. It shows James G. Crawford. So this is a guy's painting design for James G. Crawford, who was a prolific 19th century star and anoreist. For a short time, in the late '90s, he was a partner with Trenton Harnish, who was the partner of Alan Simmons, going to be a photo tent cabin here we just looked at. The sign painter is unidentified. It could be James Crawford, or it could be his brother Orville. Or it could be Harnish, or it could be Simmons. Anyways, kind of what I'd like to look at is these carton zines. Okay, the next slide, which I'm going to turn to, is a very interesting piece of art. Any questions? No? Okay. So here we go. We get to Martin Mason Heasle's art. So he was actually an incredible photographer. And he worked in Yosemite for many years in the 1860s. So he competed with Carl Watt because of people like that. He was a really good photographer. In those days, business sense was a little different. So, Heatland's eye would sell his negatives to Eastern and San Francisco publishers who would publish something. They wouldn't give him credit. But he didn't care because it just wasn't a practice back then. And so there's a lot of, which I'll show you soon, I'll just go down here in the past. Those are all published by John Soolay in Boston. And they're all from natives that handle time checks. They're beautiful, beautiful images. Okay, so the stereo view, what's that? Question. Who would be the customers for these carte de bistes in the catalog? Were they like a postcard on their day? Well, the customers would be the sitters. They had their photograph taken for their family and their friends. Like during the Civil War, it became very widespread to get your carte de bizit taken. During the Civil War, it became just exploded in popularity. And they would make Victorian albums, leather albums, and they'd have little slots, and you'd put your friends in there, you'd put Lincoln in there, and maybe Tom Thumb, and relatives, maybe Custer, when he became famous for dying. He was famous for that. So, generally, that's the end of the time photographer is the port photographer went out into the field applying test scores. And he had a big family, and he drove them around. He was an itinerant photographer. He drove all over the place in Northern California and Oregon and Washington and Idaho, Montana, but mostly in Northern California and Oregon. And he did a lot of work. And his brother, George Irby, he was nine years younger. And I'll show you. This is an amazing carte de cibie. But it's not a cbb per se. It's actually a photograph of a photograph. So this is the part of a cb image, probably an ambrotype. But it's got a protector around it. It keeps the glass off the photo itself. And the guy, so he'll tell you, it's pinned on a board. See, that's a screw, and it's pinned against the board. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. And they took a photograph of it. And then they took a photograph of it. He had two addresses he advertised during 1865. One in U-Vet. And one in Nevada City. I haven't found any photographs with a hill-times infra indicating these locations. But I didn't do that before on the Sierra Bew's mine. Which you can see right there. All right. And that's a -- it's a portrait. This is an ordinary portrait. Okay, now this is a really -- this is a really -- to me -- a very interesting photograph. So -- and I'll leave my photograph here. Let me do this. A shovel of paper. So I don't know how many of you know where Brownsville is. It's on the road between Marysville and the port. And it was an old bull road town. And many of us, I guess, back in the day. It's also where I had a law office there for ten years. And I can tell you that this -- these buildings are still there. One was a restaurant called Lottie Bremen's. And the other one was a bed and breakfast. My friend Nancy All-Brown and Russ Street was an antique store that Rex Maudsley, a friend of mine, has owned. Anyway, 18 -- whoops. In 1874, John Muir, who -- maybe he liked -- lived in Brownsville. He was a visitor. And there was a big storm there. He -- he had a -- he had an interesting character. He decided to climb a tree and watch the storm from the tree. Well, here. So anyway, that is -- let me think, John Muir right there in this rock code. And the guys over here, they're planting chess entries. So the chess that grow was planted right there. And the chess entries are still there. Those are the 8 by 10 albumin print on a period mount with a deal sign's paper label on the back. Fabulous thing. But anyway, I bought it and then I sold it. So I kept just getting it. Doable thing. So this is not very sharp. It's a photograph from the distance of a wagon. And we think it's a needle-dudged wagon. And anyway, these are stereo paths. What they did back in those days is the photographer would use the -- cut the stereos in half and make a presentation album to show what they did, what they had. He doubled their mileage with getting two photographs out of one. So anyway, they did that a lot, but -- look. Where'd he go? There. So these are from Oregon, the Crookard River in eastern Oregon. And we think those are both by Healdine. Okay, now going back to this piece. These are the stereo views that Healdine made of Yosemite. And they're very, very popular. And they sold well. There were a number of publishers that published them. Later he did his own stereo views. And they're kind of -- they're very nice. But anyway, this was a big deal, I think. And later he lived in the Mendocino. And he published a lot of the stereo views of the Mendocino logging operations in Little River, Big River, that whole area around Mendocino. And Sousaix in Boston published them. So I used to find them for my friend, Glenn Mason, who grew up in Mendocino and went to Arcadia. And he collects them. So I used to sell them to him. Okay. Now these are all samples of what we call imprints. So the photography imprint is basically his logo, his way of advertising who he is and where he's at, so on and so forth. So we've got different -- So you've got the photograph boat. You've got Thomas X's photographic car, wandering artist, likeness car, mammoth car, tent gallery. What's a ferrotype? Ferrotype is a tent type. Ferro is iron. So tent type is Latin iron. So along with the dendrotype, the emertype on glass, the ferrotype or tent type on Latin iron. So this next cabinet card is really interesting. I don't know if anyone wants to see it, I guess. Because it really tells you what you look for to figure out if it's a traveling photographer. So the first thing you notice is there is no imprint. So whoever is taking this photograph wasn't really that interested in advertising for more business. He just wanted to get the job done and get paid and move on. So there's no imprint, which suggests a 19-year-old photograph photographer. In addition, the setting of the scene appears to be makeshift, even extremely so. The marginal technical aspects such as overexposure, backdrop, clutter, and so forth suggest an inexperienced photographer, lacking tools of an accomplished photographer, which you find in town and the city. The plank floor suggests an outbuilding rather than a finished studio. The good news is that this group was fortunate to have a traveling photographer visiting their locality to capture its close-knit family portrait of what appears to be a rural family, perhaps without thought or prominent male figure. So I think this is really important. I mean, this isn't something that the market would recognize per se, but I love it. I think it's a great example of the history of the traveling photographers. And here's another one. This is. . . So this guy is. . . This guy is Will Foley at. . . Where is he at? Anyway, it's in Mississippi. Yeah, he's got it in Nashville, Mississippi, which I never heard of. He's obviously. . . This is called "Occupational. " It shows something with his tools. So I looked up Nashville, Mississippi, and the place was never incorporated. It's a ghost town now. It's located at a low point on the east bank of the Tom Bigby River, close to the Alabama border. It was devastated by floods in 1847 and 1850. It was a minor shipping port until the Civil War. It almost very continued to operate until between 1867 and 1873. This occupational cabin guard, a blacksmith, dates to around the time the dirty stuff runs. So it's pretty routine. So. . . Okay, these next two cabin guards. . . Whoop. Got the same one. They're both unidentified. They're doing print, so the farmer didn't care to advertise. So he just got doing his job, playing a It was a way for people to get the likeness of their loved ones who had departed. And now they're pretty able to collect it. So the one on the left is of a painting or drawing by a man named W. H. Boynton. Could be a woman, actually. I don't know. And on the right in the back says, "Little Johnny Pascoe died when he was eight years old. " So this is a copy photograph of this drawing or painting, and it's based on the cabin guard mount. And there's no indication of the photographer, so it's very likely to be a traveling photographer. The one on the right has no idea if you're finding words about the photographer or the subject, but it's a baby who's died. So that's another traveling photographer. Likely many. So the next group. . . One of my favorites. So one thing that someone learns in life is that young people like to have fun and joke around. I can't think of too many more enticing opportunities to do so than when the traveling photographer visits town. These three cabin cards seem to express this. Young men gathered to create visual arrangements that reflect joyful and playful moods. The paper and mounts of these three cabin cards are just being around 1890 to '95. So the one on the left, you've got four people, three of whom are male, two of your males. Two guys have top hats and aprons on, and the guy that was an apron. There's a woman in the back. She might be the owner of the restaurant or the cook, but they're just enjoying having their photo taken, which I'll share with their friends. And then the one in the middle, these three young gentlemen, if they're to be dressed or they're real cold, they flaunt pieces of paper that suggest news reporting, no idea what their message is, but they use the photo to convey their message to whomever is their audience. The third photograph is a goofy, corrugated man showing their fun, nonsensical sides to the camera, presumably so others may be amused and entertained. The rug on the floor suggests temporary staging for this scene. The man on the top right appears to be older, perhaps the father or the boss. So now we have two more cabin cards. So the one on the left is one of my favorite pretty favorites, and it's a dancing couple with wooden shoes by a traveling photographer, B. James, where in this case we got the tip off that he was the traveling photographer. He called his Operation Palace Car. And you can see it's probably a bug star on the railroad, and it's probably in the northern U. S. , probably. They're probably Dutch or German, and probably the Dakotas of Wisconsin area. I love that photograph. How long did that take you to expose her up a little bit so I'm flirting? Well, one reason they didn't smile is because exposure took a while. And this is probably the 1870s, so it probably took a while, but he captured this pretty damn well. That's the part of my English. And they obviously like each other. I really love this photograph. She had the baby and the aunt on, and they're obviously dressed for the cold. And they have the wooden shoes on. And then the galley garden next to it are a couple of baseball players. So there's no, again, there's no photographer's imprint, and they're outdoors. So it's a couple of ballplayers and probably a tiny, a tenor of stars, I think it is anyway. So, that's that. So we're getting here, I'm getting in here. So this is, so John Silva, John B. Silva was born in 1830 in Lockhaven, Pennsylvania. He traveled overland into California in the spring of 1849 to mine for gold. After many unsuccessful attempts at establishing him, Silva as a miner, Silva's learned the graph of photography in 1859 and formed a partnership with Charles Carden in my last compilation of Western photographers. It was a little essay on Carden by one of his relatives. Anyway, Silva's left and Carden kept the thing going in a solid city, kept the studio going in a solid city, whereas Silva's had this car made for the Union Pacific Railroad. So he would ride the tracks all over northern U. S. taking photographs. And you hired yourself out as a portrait star. So these are just, these are customers of his. A couple we've got the photograph taken. But this is the back of the courtesy in their traveling railroad photograph I gave you. So next we have, so these are some examples of newspaper ads in papers advertising the services of Leland Stanford Hazeltine, who is M. M. Hazeltine's son. I want to find out what the relationship was between Leland Stanford and Governor Stanford and Hazeltine. And so that's the topic I'm interested in. But anyway, he ended up in, he was up in Idaho, I think he did this. He also includes in Montana a lot and he ended up down in the Mendocino, which is a fuck word, he was a boy. And he was like, he took a lot of photographs of the shipping down there. So this is a different kind of wagon. It's also a photographer's wagon, but as you can see it's not big enough to set people and take their photographs. But you can carry around all the equipment and the chemicals and so forth that you would need to get their, get their glass negatives and take their pictures. So that's what this particular image is of a photographer in his wagon. So the next one is where we're traveling photo parlor, he calls it. This is Bryant's traveling photo parlor. I think that was used to have, shoot the photographs, but I don't really see a skylight there, but it's not the only thing at the angle. But there's no location identified, but it's great to, pretty exciting to own the wagon. Question. Pardon me? Question over here. In these photo wagons, what typically would, I mean were they partitioned off with part of the dark room and part of the studio for sitting? I think all kinds of different ways. And I think that, yeah, a really well-adclinic one, a really well-designed one, would have, that we have that kind of arrangement, you know, where you fish up and make it better than you do business. But I'm sure there's all kinds of permutations. If they know who the photographer was, how could they remember the song, the hammer, their brother and so forth. Well, you have one, right, you said? I do have one. So what's your selecting site? Well, it's an animal. I have one that has photographs of it. Oh. Yeah. Like the one I showed earlier, it's actually in the case back here, if you can look at it. So anyway, so this is probably in the particular north, whoop, in the previous one, right there. Somebody decented this to do me out of the blue. It's really neat, you know, maybe a little later, maybe a little 1890s. But obviously the family travels around in this thing, and they unload and set up, and they get customers and take their pictures. So this is an example of a photographer's wedding, his wedding child. And he's probably taking the picture. I think this is a chorus. Of course, yeah. So this is sort of the end of the talk. I love this. This is a Carte de la Zie, and a photograph car. This guy has decos, Saint Nick, and I'll tell you that's cool. And the other one is like Oregon, so I kind of had a lot of Oregon stuff. So this is the cottage car, and we're taking the picture of the van here. So it's kind of cool. That's it. The legends look so ungainly. How did they ever get them up and over origins? I don't know. It's hard to imagine. They were pretty resourceful people. I'm sure we had all of us, or many of us, had relatives back in those days that could do this sort of thing. A lot of work. Oh, yeah. More questions? Can you buy pictures from people? I guess a lot of us have a lot of pictures. Me too. Yeah, I bought a picture. Not like I used to. I get more slow. I can tell you about this. Anybody else? Come on, buy Paretta. Were all these pictures we saw tonight in your photographs, in your collection? No, some were from other people. And some I have sold, or I have a scan. So all these photographs are in the public domain. I used to study copyright law a little bit. Making mountains, writing spit, spit out the copyright thing, as much as you can, of course. All about money. But back in the 1860s, the 70s, the 80s, these were all over the land. You got the picture, you can just take off. What's the oldest picture you have? That I have now? Well, the daguerreotype is 1850s. I've had older daguerreotypes. The daguerreotype was announced in January of 1839. So in America, Samuel B. F. B. Morse, who went back to Paris, when this announcement was made, and he brought a daguerreotype apparatus with him home to the U. S. And he taught people on these coasts how to make daguerreotypes. So that was the beginning of daguerreotypes, the photography of the daguerreotype. The Americans are very resourceful, and they want to do the daguerreotype. They make some beautiful, beautiful work back in those days. So you can see this one back here, and get a chance. It's a really beautiful thing. I've seen so many people behind. What life did they use? You said 1860, 1870. They didn't have electricity. You got the sun. They were in this way then. That's where they have the skylight. Wow. I know. I remember. I do too. And people had to stay very still. Is that correct? See here? Yeah. The skylight? Yeah, they had the same very still. And here. Whoop. The skylight up here? It was that portion of the roof that opened up. And then you have in the tent, they have the light into here and here. Now, life is very important. I was just going to make a comment. I studied photography at the degree in photojournalism. And I really, I mean, to me, I don't think that they just only photograph in their wagon. I'm sure they probably did on site, people's homes, out in nature. So they weren't restricted just to the wagon. But that was their means of getting around. And if they could use the wagon to take photographs and have a bike, then they would do that. In an outbuilding farm or somewhere? Yeah. And like I mentioned, so this has the starper's information on the side, but they obviously didn't take photographs in it. Right. They would set up their equipment wherever they could bamboozle the customer alone, use their facility. When did the Garatykes and Timmy types go out of fashion? Good question. So the Garatykes, as I said, started in 1839. Actually, the first photograph was 1826. The Garatykes' partner, Gany Neeps, made that a computer. Anyway, the Garatykes started in 1839, and they just got it really popular, really fast, and spread it around, and a lot of them were made. But when the Frederick Archer in 1851 developed the glass negative. And so the glass, so the photograph on glass is called the ambrotype. It was also kept in a, where'd it go? Well, it's over there. That's a half-blade tintype. So anyway, with the technological advances with glass, it made much sharper photographs. Well, it didn't make sharper photographs. These are pretty amazing photographs of the Garatykes. But they don't reflect like the mirror, because they're like mirrors. So, you know, there I am, but I want the photograph. So that's kind of the ambrotypes that pushed the Garatykes out by, I'd say the mid-50s, or the late-50s, certainly. In England, they made them for a long time, and like as tourist things, they made them into the 1860s and '70s, the ambrotypes. But anyway, the tintypes came in right at the end of the 1850s, and the Civil War. I mean, tintypes take off as they did carton de jis, because they were smaller, people could afford them in the Civil War, or they won a picture of their brother or their father or their neighbor or whatever. So that was a big deal. And so that really spread the photography practice out there in the world. Were there many women photographers? That's a good topic. There were some great women photographers, but of course they were always my husband, you know, but there's some good ones out there. Yeah, there's some studies on women photographers, some good studies, actually. Do you have any Margaret Cameron Mitchell photographs? The camera? Margaret? I know. Because she was an early photographer. In England? Right. And she did large format stuff, and her photographs are very valuable. But I don't have any. I have one more question. When Edward Mybridge was the study for Stanford on motion, and then later on they developed a film, the callback process, what was that? Mybridge's work with Stanford was in the early 1870s. And then later on he went to-- And then he went back to Pennsylvania and worked for the University of Pennsylvania. And then for his time did it transition to some class or film? Mybridge was always working with class, negative. What was the process? He never went to film. I don't think so. No, film didn't come in total, like 18, late 80s, early 90s. And so by the turn of the century film was taking over. There's still some specialists that do it, even now, that do the old processes. I have a book called The History of the Woodbury Type, which I published for a guy down in L. A. He's Barrett Oliver. And he makes woodbury types, and he can do all the processes. So he can make amber types, or woodcullodians, natives, and friends that go through. Are the chemicals dangerous? Yeah. [LAUGHTER] A few exploding weapons. Well fired. And people would die of mercury poisoning? Maybe mercury to develop some of these processes. And if you smell of mercury then you'd go crazy or-- Good question. Could providers have a short life expectancy because of that? I think they did, actually. They did. How prolific were photographers on the East Coast? What's that? How prolific were traveling photographers on the East Coast? I didn't catch it. East Coast. The East Coast. Yeah, what about the East Coast? How many more-- [LAUGHTER] All these pictures are showing, looks like, all out in the West. Well, I'm the Western guy, you know, so-- In the East. [LAUGHTER] Pretend you're from the East. Were they prolific there? Oh, yeah. As much as the West? I can't understand what you're saying. Were they more prolific than the West? They probably had more-- No, they're all-- As the time went on and more and more people gathered in town, became more urbanized, then the traveling photographers were less and less needed to go out and get photographs. So they developed elaborate studios in all big towns, you know, like-- In Cincinnati, as a black photographer, that's pretty popular, who took a lot of great photographs back in the-- the yard type era, and then he went on from there, and he ended up in Montana and then finally see out. So, yeah, I mean, you know, it all evolved along the same lines. They were in communication. There were magazines being printed that alone took-- There were examples of people like Peter Britt of Jacksonville, Oregon. He was published in the magazines back in those days, and they all kind of kept pace with the new developments, and some were really into it, you know. They loved the new techniques, and they would get into it, they would buy the latest chemicals or learn the new techniques and so forth. So, anyway. They didn't all go for the new stuff. That's right. I have a lot of collection of a photographer by the name of Moore from Nevada City. He apparently never gave up the glass plate. I've got pictures of women in 1920s and 30s clothes on glass plates. Sure. Moore doesn't get careful for it? Yeah, that's true. Some people don't like to change. Well, black people didn't want a computer. [laughter] Mike doesn't dance a lot and he's using glass plates and some of the assembled stuff. Okay. So, how many folks think in about 20, 100 years, we'll be talking about how we transition from film to digital cameras. [laughter] Well, thank you. Thank you. [applause]

Zoom Out

Zoom In (Please allow time for high-res images to load)

Zoom: 100%