Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2023-01-18 - The Ways of Fiction Are Devious Indeed with Sands Hall (75 minutes)

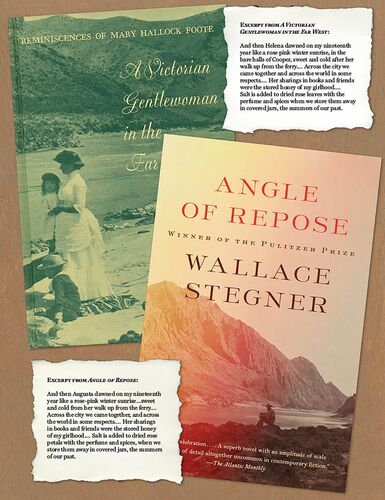

Local author, playwright and musician, Sands Hall presents "The Ways of Fiction Are Devious Indeed," exploring the controversy surrounding Wallace Stegner's use of the life and writing of Mary Hallock Foote in his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “Angle of Repose.”

From a review of her play Fair Use by the The Sacramento Bee, Scene...

From a review of her play Fair Use by the The Sacramento Bee, Scene...

Author: Sands Hall

Published: 2023-01-18

Original Held At:

Published: 2023-01-18

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

So I'm going to introduce the speaker a little bit. Jeffrey's going to be the formal introduction. If you heard us on KNCO, we have him yesterday. The interviewer talked about, well, where did you find that? On Wikipedia? And Sam says, no. That's a good idea. So I thought, well, I'll check out Sam's today on Wikipedia. Have you checked your Wikipedia? It suddenly goes right here. [LAUGHTER] It probably goes all the way up. So he's the daughter of novelist Oakley Paul, was born in La Jolla, California. Graduated Mengda Cum Laude with a Bachelor of Arts and Drama from the University of Irvine. She earned two Master's and Fine Arts degrees from the University of Iowa, one in theater arts, a second in fiction from the Iowa Writers Workshop. She also studied at the American Conservatory of Theater Advanced Training Program. So I want to just-- we have a highlight or educational background. There's a lot more to her than Jeffrey might want to add to. So we're really excited about having you tonight. Jeffrey arranged for this presentation tonight. So you're on. Thank you. Well, I'll do my best. I'm a little nervous. I'm so excited that Sam's here. My story about this all began in 1987, sitting in my wife's parents' kitchen. And I saw this book on the shelf, "An Angle of Repose. " And I said to myself, wow, that's such a poetic phrase. I wonder what it's all about. And I had never been to Grass Valley. I hadn't been much through the county. I did Tahoe and Yosemite, all of that. And so I read the book. And I said, wow, that's a cool book. And then came up here and got involved with the museum. And when I give tours, I point out the book as the literary component of the story, having it be an engineering story and a mining story, of course, and that I always relished using the book as a literary component. Little did I know that there was another book here, "Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West," that quickly became a lightning rod for this book, which, not to take much away from Sam's, is what we're going to hear all about tonight, I'm sure. And so just awesome history. I teach at Lyman Gilmore. And Lyman Ward is the protagonist of "I Go and Propose. " Just all these great historical stories became interwoven for me. And then I heard about this lady. And I had never met her. And KVMR is another one of my passions. And so there was a Christmas show a week or two before Christmas. And this lady's up there doing the 12 Days of Christmas, 260 Sling, eight nines of the little king thing. And I'm going like, wow, she looks like a really fun woman. Turns out, there she is. And so I wrote to her. And she politely replied. And she loved to come speak to the society. And what else happened? That's about it. But we are in very much awe of this lady. She's an actor, a director, a writer, a professor, a teacher. And if you look at her website, this is all evident. And I don't know a more talented person personally than Sam's tonight. And I'm just very excited to see what she has to say. She illuminates the controversy that's been stalking Stainer since quickly, after he won his Pulitzer Prize. So Sam's-- [APPLAUSE] We almost can't send this woman out tonight, but she says she's much too enamaged. She can't say so. So I wouldn't be able to hear if I was sitting down. And besides, they both stood up to speak. I am deeply, deeply honored to be here. Thank you so much, Dan. It was so fun. Of course. Just wonderful. I just love that you got to see me doing the Seven Days of Christmas. I love it. It sounds like people in the audience were there, which was great. That was the sixth piece of land that was-- They got it. So it was very antique and very fun. And we get a little bit tired tonight. We can all sing back. Yes. [LAUGHTER] I'm very aware that people in the community know this story, know this controversy, probably knew some of the people Janet McElohar and Tyler involved. And I just want to begin, whatever I have to say here, with tremendous humility. This is just the research I did and what I found. And I'm really looking forward to your questions. Should you have any at the end of the evening? I'll start by just talking briefly about how I came to know about the story. I was involved as an actor and director with the Layman's and Field Theater Company. And our artistic director, Philip Snead, had this idea that we could present "Angle of Repose" as a play. And he had in mind, some of you may have seen Nicholas Nickleby as sort of a Dickens novel that is so large and convoluted that it takes two productions to see it. So you might go on a Saturday afternoon, a Saturday evening, or two, one, even two. So that was the idea that we had in mind. Because as most of you in the room, I'm sure, know there is this double story in "Angle of Repose. " There is the narrator, Lyman Ward, which was just mentioned. And he is living-- he's got a missing leg. And he is living in a place called Zodiac Cottage, which is all bummed up and lots of graffiti on it. We're going to find out why. And he is in the process-- his wife has left him. And he's felt very betrayed. And for reasons he ought to, but whatever. And so the other story is, he is researching the lives of his grandparents, Susan and Oliver Ward. And he's claiming them as his grandparents. And he is using his grandmother's reminiscences and letters to reconstruct their life. And Lyman Ward takes the opportunity to include chunks from the reminiscences and the letters as he is making his way to this-- what becomes the book "Angle of Repose. " I believe that Stegner created a really smart narrator, very clever narrator, because Lyman Ward is an historian. So he cannot only-- he's processing all the stuff about his grandparents. But he can put everything in context for the reader so that he can actually present things that the reader might not know. Very clever. And of course, that's Stegner's own expertise as well. He knew very deeply about the Western. So we're getting together as a small group of people. There's a potential director. There's a potential playwright. That's me. There's maybe some actor or two that might be involved. Maybe some designers. And we're just jabbering excitedly about what this might be. And we're very turned on and excited. And then a gentleman named Thomas Taylor, whom some of you may know, and who's here in the room-- it was my sweetheart at the time-- says, you know, there's some local dungeon aimed at Wallace Stegner. And you might want to look into it. Something about-- he used some woman's diary who lived locally. Actually, he was more specific than that. But I'm going to play out this thing. So we all went, oh, no. It's Wallace Stegner. There's no way. Of course, we were just shocked in the poll. But we felt a little bit-- our enthusiasm was a bit dental for this project. So we go off. I'm supposed to be starting to work. And we're all-- I got our little projects to go out. And I will say at this point, part of my excitement is that Wallace Stegner is kind of a god to me. I love his work. I enjoy this book. I will say that I did not love the Lyman Ward parts of "Angela Repose," but I adored the Ward's part of the book. I really loved following their story. And I thought it was all just completely fabulous. And he was a friend of my father's, probably about a decade or so older. They both lived in San Francisco. And they had quite the literary, august friendship. And in fact, when "Angela Repose" was made into San Francisco opera company to decide to make an opera, my father was a commission to write the libretto. So there was some association there. And I was very, very much sort of longing to join that sort of patriarchal world that they both belonged to. There was this excitement about that, that I was going to be able to be on par with them, perhaps, if I wrote a really good play. So the next day, the 2B director arrives. And she brings to me this book, "The Victorian-- Victorin Judgment in the Far West," which I'm sure all of you are familiar with. She says to me, this was actually shelved next to "Angela Repose" in the local library, so for-- I mean, in a local bookstore. So maybe there is something to that controversy. And I'm like, I really don't want to know about it. I just want to get down to how am I going to dramatize this incredibly complicated book. So somewhat beautifully, I sit down, and I begin to read. And right away, I am a little bit intrigued by the writing. For instance, right away, very first of her writing-- there's a very long and fabulous introduction by the editor, Rodman Paul. "There were dark winter mornings when we woke as it were in the night, in a room where an airtight stove blared away with the draft open, panting and reddening on its legless feet. " Even now, I've got this little chat mark, and I remember making it. It was like, I love that, panting and reddening on its legless feet. So right away, she captures me. But I'm also aware of her life. Yeah, I understand that she's a quaker, and she lives up in Milton. She's got this life that's up there in Milton. It's kind of similar to what Stegna is writing about. But I'm a novelist. I come from a literary family. This is what fiction writers do. They borrow lives and ideas. My mother used to call it "Christ for your mill. " You're just like, grind it up to your mill and put it to work in your writing. So I'm like, I'm still not very concerned. But then I turn the page, and I come to this. And I'm going to pretend to read it from my book, but I'm really going to read it from my slightly larger image. [LAUGHTER] So I turn the page, and I get to this. And then Helena dawned on my 19th year like a rose-pink winter sunrise in the bare halls of Cooper, sweet and cold after her walk up from the ferry. I understand that both Susan Ward in the novel and Mary Halleck in the Reminiscences have both been accepted to the Women's School of Design in New York City. So this is where she's meeting Helena. But something rings a bell, and I sit up a bit straighter. And I read some more. She says-- I have to find that page, though. Where did it go? Here we go. [VIDEO PLAYBACK] - And then Helena dawned on my 19th year like a rose-pink winter sunrise, sweet and cold after her walk up from the ferry. Staten Island was her home. A subsidiary aunt had taken me in, that winter who lived on Long Island, and I crossed by an uptown ferry and walked down. Across the city we came together, and across the world in some respects. She was the daughter of Comunair Duque and a granddaughter of Joseph Rodman Drake. Her people belonged to the old aristocracy of New York. My people belonged to nothing except the society of friends, and not that any longer in good standing. By spring we were calling each other Helena and Molly, and we sat together at the anatomy lectures and Friday composition class and scribbled quotations and remarks to each other in the margins of our notebooks. I still keep one of those loose pages of my youth with "let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments" copied in pencil in her bold and graceful hand. And on the other side, in the same hand, the words which began our life correspondence, not gushingly nor lightly. We wrote to each other for 50 years. Her sharings in books and friends were the stored honey of my childhood. Our strings were tuned high in those days, but after we became wives and mothers and had lost our own mothers, she loved mine and I loved hers, a settled homely quality took the place of that first passion of my life. Salt is added to dried rose leaves with a perfume and spices when we store them away in covered jars the summers of our past. And I thought, hold on a minute. And I was all here in this book. And I leafed through it. And there it is, slightly smaller font, indented. And then Augusta dawned on my 19th year like a rose pink winter sunrise sweetened cold from a walk up from the ferry. Staten Island was her home. A subsidiary aunt had taken her in. On and on and on it goes all the way. And just a few things that I'll just emphasize here because they really struck me so deeply. My people belonged to nothing except to side friends and not no longer that in good standing, that with a sense of humor that comes through. We sat together in anatomy lectures, Friday composition class, the scribbled quotations to each other, including "Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds" and "Invented and It Was Copied" in her bold and graceful hands. Her sharings in books and friends were the stored honey of my childhood. And above all, because I remembered reading this when I first read the book so many years before this time, salt is added to dried rose leaves when we store them away in covered jars the summers of our past because I thought, "Paula Stegner is amazing. What kind of research did he do to know that hopefully that complicated thing that we store in jars and put in our underwear drawers is made in this way? Gosh, his research is astounding and dependent to a woman's mind in this way. " And all of a sudden, I'm staring at that statue in the feet of Playar. Got some water dropping on them. They're getting really mushy. I'm a little bit worried about my hero, Lola Stegner. So I read on. And I see more things. And so at this point, I begin to look for an acknowledgment. I look in the back. I look in the front. And all I find is my thanks to J. M. and her sister for the lone of their ancestors. We will talk about that word, lone, eventually. Though I have used many details of their lives and characters, I have not hesitated to warp both personality and events to fictional needs. This is a novel which utilizes selected facts from their real lives that is in no sense of family history. And again, I'm a fiction writer. I understand how we can warp things. We can take our dear friend Kate's red hair and does this weird thing and put it on a character because we really like what the hair does. But that doesn't mean that we're looking at the character of Kate in the red-- or we do it as fiction writers all the time. But here he is using the actual writing. I'm seeing these big chunks of reminiscences that I am now reading through and seeing all the ways he's using it over and over again. Chumps, always indented and set off in a slightly different font size. So both Susan and Mary, Robyn Milton, they both come from Quaker families. Their family friends include people like Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass. Both are artists and they're getting known. They're both getting commissions for their work. As you've heard, both Mary and Susan eventually live with their-- Susan and Mary both live with subsidiary ants and attend Cooper Union School of Design, which is when Mary meets Helena and Susan meets Augusta. But that's not, of course, the end of things. Both Mary and Susan meet and eventually Mary mining engineers, Arthur and Oliver, both go along with those mining engineers to live in New Almond in California. It's during this time that the letters that both Mary and Susan are sending back to their friends Helena and Augusta are being read with great fervor and excitement. And it turns out that Helena and Augusta are both married to the editor of Century Magazine. Yes. So these are these incredible collections of Century Magazines where some illustrations and some stories of their life show up. But this is the first time that this is beginning to happen. And the real editor, Richard Gilder, and the name that Stegner gives the real editor-- I don't know how you do that when he's a real editor of the actual Century Magazine, but he does it-- is Thomas Hudson. So they are saying to Mary and to Susan, why don't we take your beautiful letters and craft them just a little bit and turn them into essays and publish them in century? And she's like, really? Because I'm an artist. I forgot to say that. By this point, she is illustrating-- gosh, if you have any moment before you leave, take a look at the extraordinary images in the Scarlet Letter that she illustrated and these just fantastic things where she uses her family. She writes about this in the reminiscence. She uses her family as models for the various points in this poem by Longfellow, the skeleton in armor. So she is getting nice commission. She thinks of herself as an illustrator, and all of a sudden, a literary career is born. And she begins to write essays for them. She begins to write stories in fiction. So she begins to build quite a career. And just to say, I find this interesting. At no point, at least in the reminiscences-- obviously, it's her point of view that she's telling it-- does Mary seem to indicate that Arthur has any problem with the fact that she is earning money for the family with her writing and her art. Whereas in "Angela Proposed," it is very clear that Oliver-- it resents the heck out of the fact that she is successful, both in a literary and monetary way. So once that new-on-the-den job ends, Mary and Susan both hang out with Santa Cruz for a while with their respective first children. We've got Arthur Jr. , Sonny, and we've got Oliver Jr. , Ollie. While Arthur Oliver seeks work in the Black Hills with the Dakotas and other things, then all of them, all four of them, land a job well. Arthur and Oliver land a job in Leadville, fabulous section of both "Angela Proposed" and of the reminiscences. They both travel to Mexico looking at mines and mining. This trip is written about by both Mary and Susan and serialized in vivid essays that are sent back to Century Magazine, quoted lengthy and verbatified signal in "Angela Reposed. " So in Mexico, both Mary and Susan conceived their second child, a girl named Betty by Mary and very inventively by Stegner, Betsy. And both Oliver and Oliver and Arthur have a sister, Mary in both cases, who are married to a man who will turn out to be very important in their lives. This is J. D. Hay as the Foote's brother-in-law. For Stegner, it's Prager. And I just imagine going, hey, hey, Prager. I just do. Sorry. Eventually, both Arthur and Oliver turn their ingenuity to the idea of bringing water to the arid lands outside Boise. And I'll talk a bit more, actually, a lot more about that important time in their life shortly. All through, Stegner's quoting liberally from "The Reminiscences. " And I began to move back and forth between the two books. And I want to take a moment here, if I may, because I have a really attentive, educated audience that is going to be nuanced, I think, understand the nuance of what I'm going to try to do here. Not only does Stegner borrow, loan, whatever his weird word is, take these huge chunks of text, but he also does something that I find to be quite clever. In "The Reminiscences," Mary will often set a scene. She'll describe what goes on in the scene. She doesn't necessarily give lots of dialogue. She might describe how the dialogue unfolds. But she might give certain elements and details. And this is what I found really almost diabolically clever on Stegner's behalf. And I'm going to just take one and just break it down for a moment, because I think it's so interesting. "From the Reminiscences. " This is the first meeting Mary has of Arthur. And then we will also talk about how Stegner uses it when Susan meets Oliver. So first, Mary. In the afternoon, I slipped into the library. She's at a party. And in this quiet there, rubbed away at a piece of work I had brought with me, a front page drawing for "Heart and Home," which had to be finished on time. The door behind me opened with a burst of noise. I gave it again. A young man stood there who apologized for his entrance and asked if he might stay. Susan's point of view written by Stegner. Some time later, the door opened, letting in a wave of party noise. She's also-- Susan is working in the library on a drawing-- hoping that whoever it was would see her working and go away. Susan did not look up. The door closed with a careful click, which she did look up. He had such an earnest and inquiring face that she felt like throwing the drawing pad at it. That's Susan. Mary. As a matter of fact, I didn't believe I could draw a stroke with him there, but I did. I had noted the evening before when he was introduced to me a restfulness of manner that seems to go with certain occupations or with the temperaments that seek him then. We have met this man in the England Repose. She got an earnest frowning regard from an unseasonably sun blackened boy, too big for the guilt chair he was perched on. She had met him barely, one of the beaches cousin of newly arrived from somewhere. He had a sandy mustache and fair short hair. He looked out doorish and uncomfortable and entrapped. His hands were large, brown, and fidgety. You see how the characterization is really moving in different ways. He did not praise my work. He merely said, oh, jolly, it must be to have one light to make it pay. She wanted Mr. Warren to praise the drawing, but he only said, it must be wonderful to do what you'd like and get paid for it. I'll do read the rest of the scene, and then I will talk about what he does with it. So here's, again, Mary's. "I gathered that he had a job which paid, but he hated it, and was thinking hungrily of some other work that should have been his. His eyes were given out permanently. He was told by an oculus who made a mistake and cost the stunned patient his last two years at Sheffield Scientific School at Yale. No gears are wasted, necessarily, of course. He accepted the verdict and went south to raise oranges and laid up more chills and fever than money, and came north and had his eyes looked at by a better man. All he needed was the right pair of glasses. His class had graduated in June, and there it was, done out of those two years which would have put him in line with the other fellows. " OK, in that context, let's go back to Stegner's version. She wanted Mr. Warren to praise the drawing, but he only said, it must be wonderful to do what you'd like and get paid for it. Why, don't you? I'm not doing anything, not getting paid either, but you've been doing something somewhere in the sun to find this a bit for patients. "Wara-da, I was trying to grow oranges and couldn't. The chills and fever flourished a little better. What did you want to do? I started out to be an engineer and at an advanced age, he gave it up. No smile. I was at Yale at the Sheffield Scientific School. My eyes went bad. I was supposed to be going blind. He pulled from the inner pocket of his coat a pair of silver-room spectacles and hooked them over his ears, aging himself almost a decade. They made a mistake. All I needed were these. " So now you can go back to Yale, Susan says. "I've lost two years," said Oliver Warren. "All my classes graduated. " Back to the reminiscences. I find this to be really intriguing, intriguing. Mary, what worry about Yale if he had his eyes? Why not go ahead and be an engineer on one's own, I think I said. Susan said, "So now you can go back to Yale. I've lost two years," said Oliver Warren. "All my classes graduated. I'm going out west and make myself into an engineer. " So I believe that amongst the things I want to point out is that I think you've heard them, the earnest and inquiring face that Susan wants to throw the drawing pad at, which I think is kind of fascinating. Very nice, very nice. Mary Hallett footnotes the restfulness of manner that seems to go with certain occupations or with the templumens that seek them. Stegner, Susan, he looked outdoorish and uncomfortable and entrapped in his hands with a very large brown fidgety. The difference between Mary Hallett's foots, he did not praise my work. And Stegner's, she wanted him to praise her work. Mary says to Arthur in Mary Hallett's foots and the reminiscences-- and I think this is a lovely bit of characterization-- "Why not go ahead and be an engineer on one's own?" Stegner gives this characterization to Oliver. "I'm going out west and make myself into an engineer. " And then he has Susan laugh at this and say rather snottily, "It just strongly is funny for someone of the Beacher Blood to become an engineer in the wild west. " So you can see, and why I bring this up and spend a bit of time on it is partly because I just want to share this sort of deep work of the comparison of the two pieces. But also because over the book, this becomes incredibly important. Who Susan is is very, very different than this incredibly adventurous, leaning into life woman that Mary Hallett's foot is. And Susan comes across to me much more as sort of a disgruntled housewife. So here I am, looking at a movie and I'm thinking about my play. And then I think, well, now there's all these letters in here that this woman is writing to her friend, that Susan is writing to her friend Augusta. Surely, surely Stegner has written those. And partly I'm thinking this because my father had told me a story about-- he has a novel called Warlock. It takes place in the old west, which had been nominated for a Pulitzer. And I remember him telling me that there were these letters from the man that ran the grocery store in town, Mr. Goodpastor. And he wrote Mr. Goodpastor's journals. And an editor at the publishing company said, you can't just copy someone's journal. And dad's saying, no, I wrote the journal. He was very, very proud that this editor thought that they weren't actually period pieces. So I had this in my mind. Well, surely he must have then written the letters. So at this point, I don't quite know what to do. Turn back to Tom Taylor. And he introduces me to Tyler Miccolo. Some of you may know or have known Tyler Miccolo. And of course, he was married to Janet Miccolo, who is, of course, the J. M. of Stegner's acknowledgement. The J. M. and her sister for the long-- there's actually two sisters, but he only says one. So Tyler is incredibly excited that I have been turned on to this project. He hands me folders of information, including the correspondence between Janet, Miccolo, and Stegner about getting the materials. And he also says to me that the letters of Mary Hallockfoot, for reasons I'm about to explain, are stored at Stanford University. So I get in my car, and I drive down to Stanford. And many of your historians have probably done this work, where you order up some boxes from the archives, and you put on your white gloves, and you wait, and you're so excited for them to come. And the boxes come, and you go through them. And it's amazing and incredible. And he copied those letters verbatim. I mean, I have all of that written in the margins of my angle of repose as well. So I'm feeling a little outraged, and I'm set. And I go back to the group, and I say, we're not going to do a play based on angle of repose, because even though I really want to join the patriarchy, I'm really not wanting to give Stegner any more credit than he's already received for this book. And for the life of the foots, which partly was so amazing, but I could imagine-- and I kept thinking about what it would be like. Mary Hallockfoot and Wallace Stegner could be in a room and talk. I really-- yes, I really wanted that to happen. But of course, power could have happened. The one place I could imagine it could take place would be in the wonderful limbo that theater and the stage provide. But I'm getting ahead of myself, because all of that was here to finish a comment. So how did Stegner come to have access to the letters and Roman instances? Well, he appears to have been aware of Mary Hallockfoot and her writing in the 1950s. Stegner taught her stories in a course at Stanford called The Rise of Realism. He told a person with whom he did a lot of interviews that she was one of the best and hadn't been noticed. And a graduate student of his named George McMurray, thinking he might pursue a dissertation on M. H. F. , tracks down her descendants here in Grass Valley. And in a 1957 letter to Stegner, McMurray writes that he's met with Janet and Tyler Michelot, and that-- this is a quote-- "They gave me two more cartons, each as big as the one in the Felton Room, a prime M. H. F. material, including nearly 200 of her sketches, all her brisket beans, reviews in family and fan letters. " So they've already-- the family's already given them a lot of material, and now he has a whole bunch more. McMurray was supposedly working on the novel, but his letters to Stegner-- fascinating to read. For some reason, Tyler has them. Tyler Michelot, when they're in the folder. And his letters to Stegner, who was his thesis advisor, they demonstrate he's entranced by M. H. F. , what you can see. It's kind of easy to become entranced by M. H. F. , but he collects her out-of-print novels, and he is working on a biography, and he has taken those letters that were written to Helena, which had been sent back by the family, and he is transcribing them. He's typing them up. So there's evidence the Stanford Library wants more of this M. H. F. material. And of course, the Michelot's are thrilled at the idea that such attention might be paid to their ancestors. Janet is the daughter of Arthur. So she's a granddaughter of Mary Hallock Foote. She's the daughter of Mary and Arthur's son Arthur. So in March 1957, Stegner visiting Grass Valley asked to meet with the Michelot's about your grandmother. Now, I don't have his side of the-- Janet's side of the correspondence, so you have to guess this. A month later, a letter indicates he's returning some M. H. F. stories. They have loaned him, and he says he's encouraging McMurray's biography, and I'm really glad that he's editing for parallel publication, The Reminiscences, because right now they're in unpublished manuscript form. 10 years past, in August 1967, Stegner writes that McMurray, quote, "has got pretty old, and it's clear he is not going to get on with that biography. He has given me the typescripts of the letters, and I have been reading them, and I see why the letters excited him. " While Stegner says he doesn't want to do a biography of the foots, he can see that out of there, so typical-- I find that really interesting word-- out of there, so typical and so comprehensive life, I might work out the outlines of a big Western novel of a kind I have not yet seen written. He adds, "since it would involve no recognizable characterizations and no quotations direct from the letters, I assume this sort of book is more or less open to me. " And in a p. s. , he adds, "do you know the location of your grandmother's reminiscences?" In September, he acknowledges Janet's prompt reply in October, he thinks, for sending the reminiscences. By February 1968, he's read them quite a book, really, and I'm quite a wife. I'm all the more persuaded that it ought to be worked into something. I'm all the more eager to try and do it. Then, silence. Meanwhile, this other intriguing thing happens. The son of Arthur's brother-in-law, aforementioned J. D. Haig, encourages the Huntington Library Press to publish a magens reminiscences, which they are delighted to do. And in March 1970, Janet receives a slightly panicky letter. Probably. You thought I was dead, paralyzed, struck, dumb, or otherwise incapacitated. I am none of these. This is Stegner. Thank you. From Stegner, Janet receives a slightly panicky letter from Stegner. Probably, he writes, you thought I was dead, paralyzed, struck, dumb, or otherwise incapacitated. I am none of these. I am only slow as a sinful conscience. Ron McCall, the extraordinary editor who worked on this, on the reminiscences, has just fun, Stegner, with news of the forthcoming publication. Me, I think it's a splendid idea, Stegner writes. But must I now unravel all these little threads I've so painstakingly rabbled together, the real with the fictional and replace all truth with fiction? Or does it matter to you that an occasional reader or scholar can detect the foots behind my fiction? Thank you. The news of the imminent publication of the manuscript and what she was basing his book was no doubt unsettling. As long as there was no copyright, Stegner was within his legal rights to borrow from it freely. I don't know where that's actually going to be actually OK anywhere, but he is legally OK. Above all, unraveling those little threads would have destroyed the novel. It seems to be at around this point that Janet simply says, well, let's change the names. Just don't use any family names, which is where we get the Susan and the Oliver and the Betty and the Betsy and the Arthur, Sonny and the Ollie. It was very, very clever work of changing the name. He adds in this letter, "For reasons of drama, I'm having to throw in a domestic tragedy of an entirely fictional nature, but I think I'm not too far from their real characters. " A month later, Janet has written back, and thanks her for the "vote of confidence. " Then he adds, "Do you want to read this fat 600-page manuscript when it's finished? Or would you rather wait till I can send it to you in print? As I've already warned you, it wouldn't do to look for your grandparents' lives. And it only is sort of outlined in flashes. All of it bent where I needed to bend it. " We don't have Janet's reply, but it's clear she demured from reading that fat manuscript. So the novel is published with the threads intact, marriage-like bent when he needed to bend it, and including the domestic tragedy of an entirely fictional nature. That was 1971. The reminiscences were published in 1972. The same year, "Angle of Reposed" won the Pulitzer Prize. [LAUGHTER] So I have lots of other little details I'd love to share with you, but I'm going to move along to Idaho. So one of the things-- the first draft of "Fair Use," which I did eventually write, if I called it "Fair Use," I fell so in love with Arthur and his extraordinaryness that the play almost became more about Arthur than it became about Mary, which I think is kind of interesting. But amongst the things I adore about Arthur is that he was in a business that required the exploitation of men in terrible, terrible working conditions, deep in minds, horrible things like having to strip down and have their butts checked so in case they were taking gold out, just completely exploiting and just these disgusting things. And he had come up with this plan that out in Idaho, around Boise, this little town, there was erudeness. And then he could turn the Snake River and cause it to run through a canal and go through Boise and irrigate all around Boise. He could bring water to these errand lands and make a lot of people happy and be outdoors and up all around while doing it. Oliver is given the exact same dream. It's called the Big Ditch. I think kind of fondly-- I love this about the foots. They just gave-- she's rubbing away on a painting and they call this humongous project the Big Ditch. They just had a great sense of humor. So they have money behind them. There's so much detail I'd love to give you. The money dries up. There's more money. There's a terrible recession. They create a pretty extraordinary and very hard life out there. If you read the rims. And I just want to say that this wonderful book by Stacey Will-- I stayed with her when I did a staked reading of my play in Boise right on the canal, by the way, so I could just see the water that Arthur had planned. But this is a pretty amazing book because she talks about-- she goes through all the letters and she finds out the decor that would have been the house. And this is a house they built as Mary Hallet Foote writes about it out of the native earth we stood on. And she says, of all of our wild nest building, this was the wildest and the hardest to leave. It's just an amazing story of building this house. So they actually-- in Mary's part of things, they actually created some pretty happy circumstances. And she just writes about it so well. One of my moments that I want to say is that they're arriving for the first time. She and Arthur, Sonny, Jr. , and Betty, the daughter, are all arriving. She writes-- this was a big laugh line in Boise because Kuna now is a hub of many, many-- one. Yes, thank you. No one remembers Kuna. Huge laugh line. Anyway, here she writes, no one remembers Kuna. It was a place where silence closed about you after the bustle of the train, where a soft, dry wind from great distances hummed through the telegraph wires, and a stage road went out of sight in one direction and a new railroad track in another. But that wind had magic in it. It came across immense dry areas without an object to harp upon except the man-made wires. There was not a tree in sight, miles and miles of pallid sagebrush, as moonlight unto sunlight was that desert sage to other greens. It gives a great intensity to the blue of the sky and to the deeper blue of the mountains lifting their snow-capped peaks, the highest light along the far horizon. And you can see what fine illustrator she was because of the language that she uses in this way. Also, this is her response to their first thing. We're bowling along in our light livery ring, she writes. From time to time, the front seat looked back to see how the back seat was making it and how we liked it on the pole. We liked it very much. Over there, we were told, was a sawtooth range where the Boise River heads up in southern Idaho. War Eagle Mountain and his brethren of the O'Waukes, might be 50 miles away. There was no guessing distances in that pure light and a featureless perspective. We were driving straight across the drainage, and the wife of the new irrigation engineer marked the phrase as part of the language he was expected to know. We came out on the last long bench above the Valley of the Boise and saw, across a bridge in the distance, the little city which was called the Metropolis of the Desert Plains. The heaven of old teamsters and stage drivers crawling in at nightfall. We saw the wild river we had come to tame, slipping from the hold of the farms along its banks that snatched a season's crops from it as it bled. Multiply that in constant water a hundred fold. Stored in these reservoirs, the mam talked of building up in the crotches of the hills. Covered the valley with farms, and even to the mind of the misbeliever, here was a work worth spending a lifetime on. So that's Mary Palak Futt's perspective, right? On what her husband has come here to do. So beautifully phrased. Susan is a lot less enthusiastic. [LAUGHTER] So in those 10 years, they take a decade out there, hoping and grieving and praying for this dream to happen. Susan has no miscarriages. Stegner just leaves those out. But miscarriages were a huge part of both her and Helen's lives. Helen had a startling number of them. Mary has a number that she mentions very briefly in the reminiscences. But both of them, finally blessed by a second daughter through a child. Both, in this case, are named Agnes. Stegner does not change the name of the youngest daughter. And just another little short piece of writing to let you know. The day had been both babies were born with a double rainbow across the canyon. And Stegner uses that in his description of the baby of Agnes arriving. But this is-- The day had been stifling hot with showers around us on the mountains cutting off our down canyon wind. The baby came at sunset. And out of the window of my room, they told me a double rainbow could be seen spanning the hills where the river enters the canyon. A sight so beautiful that he, who did not know that he had another daughter about two minutes old, came to the door and begged them not to let me miss this welcome to our canyon baby. I laughed and think of it afterwards how Bessie, her sister, held the door against him and said, she is not thinking of rainbows. Heaven and all its rainbows could not have sent me greater peace than I owed that night to my tired sister on the cot beside me. Not awarded, she said about her descent upon the cloud. She had given its first bath to the new baby that lay cradled between us in that trance-like sleep, which ushers in the troubles of the world. The wind rose in the night and came rushing past the house with the sound of the misty in the air. It was mid-summer night. The fairies might have been abroad on that wild, soft wind bringing dreams. We name the new baby Agnes. She was quick on her feet, resilient in spirit, yet rested in speech, full of a mysterious, lonely joy, as if the fairies of her birth night still kept her company. And double rainbows that no one could see stood in her dreaming skies. So that's the kind of language which entranced me. You can tell, and I just love so much. In his conversation with Wallace Stegner, historian Richard Echelin dedicates a chapter to Angela proposed, and in it Stegner is often defensive. It has nothing to do with the actual life of Mary Hallock Foote, except that I borrowed a lot of her experiences, he tells Echelin. And the Mary Foote stuff, his word, had the same function as raw material, broken rocks out of which I could build any kind of wall I wanted to. Contemporary reviewers and writers, with few exceptions, men-- of course, I had those jobs in those days-- defend Stegner with a no copyright argument, or insisting, as Stegner himself did, that the family had given him permission. But that permission, if it was indeed granted, seems to me to have been secured under false pretenses. There's that 1967 letter in which he tells Janet that the novel would involve no direct quotations. In 1970, he assures her that it wouldn't do to look for your grandparents' lives in it, only a sort of outline. For many people, the only excuse needed is that Stegner created a great work of art. I've heard this one many, many times. But whose work of art is it really? When Angler proposed was released, the New Yorker described the board's triumphantly on American Odyssey. They did not include a single mention of the very ingenious narrator, Lyman Ward, just the foot story or the ward story. The New Statesman wrote that Susan is the book's great strength. And the Atlantic Monthly praised Stegner's ability with voice, especially Susan's, in letters that are a triumph of verisimilitude. Verisimilitude. Play-doh. Yet in the end, it wasn't that Stegner copied so much verbatim that incensed me. And in this, I have partly to thank the other sister that isn't married mentioned in Stegner's acknowledgment, Evelyn, who really pointed this out to me. It wasn't so much that he copied so much verbatim, nor that in creating wards like he followed so precisely for 523 of the novels, 569 pages, the trajectory of the foot's lives. It was then in the process he altered Mary's character. By giving you just a small little sense of that. I had other ones, but I know I've got to come to a close soon. It was then in the process he altered her character. She emerges to me as a griping, entitled, discontented, 1950s housewife. [LAUGHTER] And I'm saying nothing like the adventurous, deeply intelligent, resilient woman on whom she was based. One of my favorite moments in one of the letters to Helena is that they go in a boat down the Snake River, which is going, pshh, in the spring. And she writes to Helena, the worst that could have happened was we might have hit a rock going at the tremendous speed and had to walk home in wet clothes. [LAUGHTER] You know, you just love her. Just amazing. In addition to the little penny quality that I believe-- not everybody agrees with me-- that how Susan comes across is he sets up this flirtation with one of Oliver's assistants, Frank Sargent, which gradually and predictably becomes something more. Having established that affair, and once more, the money for the big ditch has dried up. Just 50 pages from the end of the novel, the story of the foots and the wards finally diverges. On page 523, this far from the end of the novel, he writes, up to now, reconstructing grandmother's life has been an easy game. Her letters and reminiscences have provided both event and interpretation. But now I am in a place where she has not done the work for me. I have to make it up. [LAUGHTER] And make it up he does. [LAUGHTER] The flirtation reaches some kind of boiling point. Susan is off somewhere with Frank. We don't know what they're doing. Stegner's incredibly coy. I mean, maybe he just touched her foot. And while they're off canoodling, or not canoodling, whatever they're doing, she loses track of her daughter, Agnes, who drowns in an irrigation room. Frank's sergeant realizes that Oliver's sorted things out and blows his brains out. Oliver is so upset that he pulls up all these roses that he's planted for 10 years. Great, huge scene in that novel. And you won't speak to Susan for the rest of their days. This is Stegner's domestic tragedy. This is the part of the foot's lives he bent when he needed to bend it, while also telling the family, but I think I'm not too far from the real characters. And Stegner had a good sense of what he was doing. In 1971, he sent down a copy of the published novel, I Send This to You with Trepidation. You may have expected me to stick to your grandmother's real life and character. And that I found I was unable to do. I had to warp it. It warped itself. In effect, I make your grandmother bolster with her authentic letters the false portrait I am painting of her. The ways of fiction are devious indeed. In fact, when the big ditch went belly up, Mary worked like a fiend, writing stories and essays and providing illustrations to make money for the family. Arthur looks everywhere for work. Amongst the things I loved during this period is Mary is in touch with Rupert Kipling, and she's complaining that she's writing pop boilers. She's providing illustrations for a poem, I think, that's different. And Kipling right back, he says, that's OK. That's all right. If it boils, it pops. She says how much that meant to her, to get that little accolade. So it's great times pass. Things are difficult. Eventually, Arthur's brother-in-law, J. D. Haig, offers a position. It takes some time as position of the superintendent of the North Star Mine. They test him for about a year and a half to two years. They have him down here. Mary's still up in Boise. They're trying to figure out if he's dependable. He has things like he doesn't want-- once he becomes superintendent, he won't-- once electricity gets invented, he won't put electricity and men in the same mine because water is in mine, and he doesn't want to endanger them. So even men, when he was becoming superintendent, he took care of men, but he's men. So the same thing happens, of course, for Oliver with his brother-in-law, Prager. And finally, the tapestry of the novel returns to its original source. The foot speaking and the wards not move to Grass Valley for the wards of the Zodiac, for the foots the North Star. And tragically, Mary's daughter, Agnes, also dies young. Not as young as Susan's Agnes. Agnes dies at 18th of Pentecilitis. Mary was so distraught by this death, she did not write again for 20 years. And when she did, it's a beautiful book, in which she kind of imagines-- it's called The Groundswell-- in which she kind of imagined who Agnes might have become. Just incredible. And she becomes a feminist, actually, which I find fascinating, because Mary had none of that in her. She didn't believe who ended up alone. She was fascinating. Whole lot of talk, I think. And that's the Mobius twist for me. Those that don't know, the foot-ward connection thinks Stegner invented those astonishing lives and all that wonderful writing and the sorts of details that he's included that I've shared with you. Those that do know the connection think that Mary Foote, like Susan Ward, is not only a disgruntled wife, but far worse. A woman who cheated on her husband, as a result of which her daughter died, as a result of which the couple lived utterly estranged out there at the Zodiac. Or is it the North Star mine? Because Mary, how that foot was a big snob, and she didn't really take to her grass-belling neighbors, it was very easy to imagine the two of them out there, I'm sure, being quiet with one another. Arthur had a bit of a drinking problem. He would periodically go off and pick out on a bender and then come back. There were all these things that the community kind of knew. So they could actually supply Evelyn, the third daughter of Arthur, Janet, Nicola's sister, sent to me two things. One, she said, that was the most devastating thing for the family, that everybody thought that Stegner had uncovered a skeleton in the closet and they'd say, everybody has one. He just found out yours. But she also told me a wonderful story. She tells, she's probably about five years old out of the North Star, and she remembers Mary coming home from a long trip somewhere. And Mary stood very small. She was maybe 410, 411 at the slightest. And she said she remembers that Arthur was lying down on sofa and that Mary came in the house, ran across the living room, and it just jumped on him. So I don't think there was a lot of no talking going. So two little points, and then I'd like to open it up for questions. The first one, and I'm just really disappointed that Stegner did not include this because I think it's so remarkable. Arthur's dream did come to fruition. Years after they'd anchored at the North Star, Mary Hallock Foote-Weisz, in the reminiscences, deep in deep mining, the old Idaho dream came back to us with its sound of wild waters between dark basalt bluffs that cut the sky. Arthur's assistant, while he's still in Idaho, has sent them a news clipping from the Boise Statesman. In it, a quarter of a century ago, Arthur Foote saw where water could be diverted. He saw where it could be stored. And in the reach of his precise imagination, he could see these lands peopled with thousands of prosperous families. Although it took the force and wealth of the US government to make it happen, Arthur's big ditch is finally finished. 3,000 people lined its banks to see it open. The entire area continues to be watered today by his vision. It is an extraordinary thing to visit and see that beautiful green city and to fly in and see all green around it. That was his vision and the team to pass. And finally, angle of repose, many of you probably know, is the angle at which Earth will no longer slide. So I often think of it when I'm taking a turn on a freeway and the difference between a really well-banked one, when you kind of go down, the car just does this, and one that you kind of go, ooh, ooh, ooh, ooh, ooh. I feel these engineering turns. There's a reason engineer and ingenuity and ingenious are all connected. So this is Mary Hellecfoot looking back on those bleak years in the canyon. She's sitting-- she's remembering sitting with her husband and the two assistants. And she says-- she writes, "Often I thought of one of their phrases, the angle of repose, which was too good to waste on rocks, lads, and heaps of sand. Each of us was slipping and crawling and grinding along, seeking what to us was that angle. But we were none of us ready for repose. And I cannot help but know that Stegner, reading the reminiscences, came across that phrase and went, bingo. " He has Lyman Ward defining it, intriguingly, as horizontal permanently. Whereas I think this phrase sums up Mary for us so beautifully. Each of us was slipping and crawling and grinding along, seeking to us what was that angle. But we were none of us ready for repose. That's how she lived her life. She leaned in. She was excited. Tremendous woman of this last century. And I just feel so honored to have an opportunity to share a little bit of her life with you. Thank you. [APPLAUSE] [APPLAUSE] You can see I get emotional. [LAUGHTER] But you can see why I love her. She's just an amazing human. And their lives were amazing. I'd be happy to answer any questions. You can also just go to refreshments and I'll hang around. But let's take you and then you. Yes. In 1994, I talked with Eveline. And she was talking about how they were collecting papers and some of them were going to put it in a book. Were you that person? No. This is a story that she talked to Eveline in 1994. And there was talk of what it was, was trying to get both Helena's letters to Mary and Mary's letters to Helena in a book. And that project has been going on. It's still going on. But it has never come to fruition. Now it's passed to somebody. I think she was a professor at Boise State. But now I think she's retired. But it continues to be a vision. But it hasn't come to pass yet. Yeah. Yes. Thank you, Sam, for a marvelous presentation. So Mary Foote's grand nephew, James Haig, persuades the Huntington Library to publish her memoirs. At the same time that Wallace Stegner's working on the novel, is that a coincidence? Or does Rodman Paul's sort of warning letter to Stegner suggest that maybe it wasn't? And it may be a question that's not answerable. But I-- My own chromies into this exact same question have revealed that it was really a coincidence that Janet was-- she was aware of the reminiscences being with Stegner. But that it was James D. Haig who was wanting-- because there was a lot of material of the-- because James D. Haig's grandparent was an enormous force in the mining world. He knew everybody. He financed things. He bought things. He was a huge force. And a lot of those papers reside at the Huntington Library. So James D. Haig, the grandson, understood that, knew these reminiscences existed, and thought it would be nice to honor his great aunt. So I think that was how it came about. But I think that then once that began to unfold, Janet let Rodman Paul know that Stegner was working on a novel about them. And so then Rodman Paul's thinking, oh, and he does-- Rodman threads that line very, very carefully in his introduction to the reminiscences. Because Stegner at this point is this abussed creature. And how can you tackle it? And so he threads that needle in a really touching way. He makes an effort. But I think they were pretty disconnected. It was a coincidence. But Rodman is the one that clearly lets Stegner know. Thank you. Yes, Sandra. So was Stegner ever called on this? Yes, he was called on it by various academics. There's a woman who wrote an essay, Marion Walsh, who wrote an essay called Succubi and Other Monsters, in which she took him to task or to tell. Really intense thing. In fact, it was so virulent that it didn't serve any purposes. Because it allowed Stegner to go look at these crazy women, and how they talk about me. As recently as after my play-- I forgot to talk a bit about my play. My play eventually became a fair use of it. I called in-- there was the 45th or 40th anniversary of "Angler Opposed" or something. And Michael Krasny had Richard Echulain on his program. And I called in to cheerfully say, well, is there any conversation about the fact that there's a lot of that book that he didn't make up? And Echulain says to Krasny, he says, look at these women. All they want to do is bring a great man down. So you can see that my desire to join the patriarchy chipped it. So he did get called on the-- here's a little thing I think is really interesting. Completely, completely conjecture. More and more people began to find their way to Mary Halepfoot's diaries, and the reminiscences and the letters, because more and more women were becoming interested in lives of women. And it wasn't just men any longer, looking at them. And people were pouring over like journals of women who came across the plains, looking what that little dot in the upper right hand corner means she got her period. The little x means her husband. But maybe they had sex because she's pregnant. So people are-- they're pouring over the minutia. So a lot of attention began to be paid to this rather remarkable person. And ironically, attention paid to her turned attention to Stegner. So he began to receive a lot of letters saying, could you please explain the connection here? And why did you change all the names but not Agnes? He writes to that one. No, no. I invented Agnes as I invented the drowning. That's one of the letters he wrote. But this was, I think, in 1993. He was pressed pretty hard in a letter about various details. And I think it's just interesting because you know how when you're distracted and you're upset about something is when you drive over the curb or you're back into the wrong thing or whatever because you're not really paying attention. I think it's interesting that in 1994, in Albuquerque, accepting an award, Stegner had the car accident that led to his death. I think that he was understanding that stuff was beginning to come in, that more and more questions were being asked that he wasn't going to be able to answer. I don't believe that he causes no death. I don't mean that. I just mean I think that he was distracted. And that's complete conjecture. It's completely conjecture. It's my ooty-wooty weird thing I do, right? It's just conjecture. But I think it's really intriguing because those letters were by the early '90s, they were really beginning to ask very pointed questions about the differences between the fictional Susan and the changes he had made. No one had really noted yet that Mary did not have an affair. How do you actually know that? Maybe she did. Maybe Stegner knows something we don't know. But from my reading, that is not in her character. And it wouldn't have happened. So that didn't seem to close in much. But I think the questions were beginning to happen. Get closer. I do. So Mary was out in the Wild West. I mean, in Mary, where it was not a lot of press and publication and acknowledgment. And yet she was prolific in both her writing and her art. But how acknowledged or how much accolade did she actually have during her lifetime? She was very well-known. And she was very well-reviewed. Amongst the things I find really charming in the reminiscences is when she shares that these miners have one copy of Century Magazine. They have the little Century Magazine. And they're passing it around amongst themselves. One can read reading to the others. And one of the letters comes signed by 14 miners, starting with old Jack and ending with the kid. And they ask, how do you know these things that the eye of woman hath not seen? And she writes back and says, because of my engineering husband, blah, blah, blah. So she was popular in interesting ways. But she also-- in an interesting world, like the fact that she's being read in mining camps. And she's reviewed well. She was published, I think, other ironies, published by the same company that published most of Stegner's novels, "Happenitlin," published the same amount of novels as he did. I mean, I think there's some really-- they were both essayists. They both. And another irony I think is really fascinating is that Stegner really did so much work for the West about the environment and everything else. But he had a house in Vermont that he went to every summer. And when he died, he asked that his ashes be scattered there. When Mary and Arthur backup-- Arthur Jr. becomes superintendent of the mine. And they go back east to their family to Betty-- excuse me, yes, Betty. And he dies and is buried there. She dies. And she asks for her body to be cremated and brought back so she could be very beside her daughter, Agnes, in the graveyard that is at the very, very back of the grave, the cemetery that's opposite Llamy Gilmore. There's a little enclosed place. And you can see her, A. D. Jr. and Agnes' graves, amongst others, are way back there. So I find that to be amazing. She kind of always had this yearning for the East, partly because of Helena. But she wanted to be buried in the West. And he was this big Western guy. And he wanted his ashes in the East. I just find these to be fascinating little details that connect to each other. Yes? Not to make it all of that well-saved, but why? This guy was inspected, revered, had a huge career. Why would he-- what's he doing? What does he think he's going to get away with? Yeah. I have two thoughts about that. I'm sure the people in the room do too. One is he writes himself. He says to Richard Echelin that he was without book. And then he came across this material. And he found, he saw what he could do. And I think that once he began to look at her writing, he knew he couldn't actually talk her writing in trying to get the scenes across. He wanted to get across. So he incorporated it. There's a great moment in the play. I really try to completely honor it, where Mary-- Arthur picks up Mary at the train in Denver. And they have to go up over the pass into Leadville. And this horrible-- it's snowy. It's the last pass. It's going to be-- it's just things are going badly. And the horse is dying to altitude sickness. And he borrows this for Susan and Oliver. And both of them, both Arthur and Oliver, get out and lash the horse and force it up and make it die. Until it drags itself. And Susan's like, oh my god, this is really intense. And Susan's hating his violence, hating the cruel west. And she sits there shivering. Whereas in Maryhounds' foots, like we dined at the Clarendon and oysters and-- she's obviously totally into whatever had to happen to that horse. So it's completely different. But they move that scene. He borrows very well and writes very beautifully about it. But it's the same thing. There's this great moment when they're coming down. They're going up. And around the bend comes a huge stage coat with eight horses pulling out. And Arthur and Oliver have to run the buggy up the side of the hill to get out of this way. And they go horses and horses and horses go by. The steam-- they're both mentioned. Mary writes about the steam coming out of the horses. And now there's a little segner. Wonderful detail of Maryhounds' foot. And there was-- Arthur and the driver exchanged a small stern grin as they passed. And Stegner borrows that too. So I just don't think he could top it. And then I also think that he never thought that anybody would mind him. I think he thought she was a-- he said, she just wasn't interesting enough to make her the topic of a biography. By converting her to fiction, I had the chance to make her immortal. That is pretty direct. And I think he just-- when I say before, I don't think he dreamed that women would be going through diaries, that women would begin to be interested, that women would have this kind of power to be able to ask these kinds of questions and get and want the answer. So I think he just couldn't imagine it. And that was, I think, the little devil's agreement he made there. But I will always ask about that. You mentioned the play that he finally came about, the dialogue between the two of them. And I forgot-- fair use. It's a copyright term. And I understand it has been performed here in the past. Would you ever think about reliving that? Absolutely. I've had numbers of fabulous outings, readings. It's a fundraiser for the North Star House two times. And a full production at Foothill Theatre Company. A full production up in Boise. There are for obvious reasons, obviously very interested in the story as well. And two stage readings up there as well. I'm currently wooing Capitol Stage in Sacramento to please put a production up. It's a very fine professional theater. I think there's about a 0. 001 chance that they would take it. But if anybody is a subscriber, write them. Say, I just heard Sam stop getting it. I can't get to leave the academy. But there is a local theater company that's approaching me about the possibility of doing it. And if this falls through in Sacramento, I will probably accept their proposal that we do it here. Because it would be lovely. I'd love to have a professional theater company do it for all kinds of reasons. But it's really a story. You can see that it's a story worth telling. For me, the angle of the proposal I'm trying to get at is that as many people as possible know the difference between the Foothill's lives and the Ward's lives. That's just really, really essential to me. [APPLAUSE]