Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Other Videos

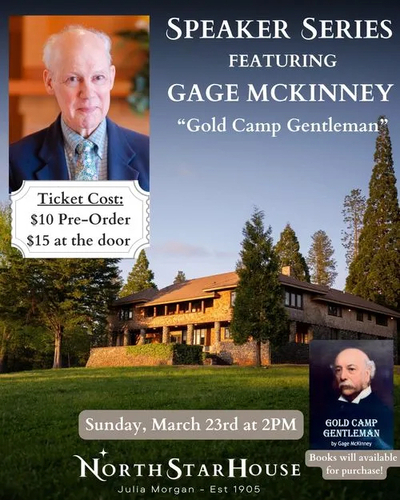

Video: Gold Camp Gentleman - James D. Hague (March 23, 2025) (77 minutes)

Join author Gage McKinney for a special presentation of his newly released book, Gold Camp Gentleman: A Life of James D. Hague, at the historic North Star House on Sunday, March 23rd at 2pm. This event will shed light on the life of James D. Hague, a man whose contributions to Nevada County and the gold mining industry have long been overlooked. McKinney's new book brings his story to the forefront, revealing a remarkable life intertwined with California's history, including his pivotal role in building both the North Star House and the North Star Powerhouse. The event will be attended by three generations of James Hague's descendants, making this a truly memorable gathering.

About James D. Hague: James Hague, a Harvard-educated engineer, was instrumental in securing the future of North Star Mine and employing generations of Grass Valley workers. He played a key role in bringing important figures to the area, including engineer Arthur D. Foote, illustrator and novelist Mary Hallock Foote, and the renowned architect Julia Morgan. Hague was also a man of science, befriending great minds like Charles Darwin and Theodore Roosevelt.

About Gage McKinney: McKinney is an award-winning author and historian recognized by the Mining History Association, California Pioneers, and the Phelan Foundation for his work on California's mining history. He has also been honored by the Nevada County Historical Society and is a reader at The Huntington Library in San Marino, CA.

About James D. Hague: James Hague, a Harvard-educated engineer, was instrumental in securing the future of North Star Mine and employing generations of Grass Valley workers. He played a key role in bringing important figures to the area, including engineer Arthur D. Foote, illustrator and novelist Mary Hallock Foote, and the renowned architect Julia Morgan. Hague was also a man of science, befriending great minds like Charles Darwin and Theodore Roosevelt.

About Gage McKinney: McKinney is an award-winning author and historian recognized by the Mining History Association, California Pioneers, and the Phelan Foundation for his work on California's mining history. He has also been honored by the Nevada County Historical Society and is a reader at The Huntington Library in San Marino, CA.

Author: Gage McKinney

Original Held At:

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

Welcome everyone to the North Star House. I'm Ken Underwood and I'm the Secretary of the Board of Directors and I just got that to introduce for you. First thank you for those who have been here many times, great. I hope you can see the house and all the progress that has been made. For those that this is the first time, well welcome. This is quite a surprise I'm sure for you. Maybe you saw it 20 or 30 years ago, but it's really been a lot of progress. So I want to invite you to come back and enjoy all the events that we have planned. Today's very special. I'm sure you know what the reason you're here is to hear about the Haig family and their relationship to the mining and to the North Star and all the work that happened here in the late 1800s or early 1900s. But I'm very glad to meet the family and glad to see them and maybe be able to tap their brains a little bit and find out more about what their lives were like here. Our speaker today is Gage McKinney. We know him because he's part of the North Nevada County Historical Group and they have their meetings here. They have shared many of their findings, many of the results of their historical searches with us so that we can really enhance the story that we're able to tell about the North Star House when people come to visit. And also just how to restore the place and make it back to fulfilling the same goals that it had even 120 years ago. So Gage is the award-winning author and historian. He's been recognized by the Mining History Association, the California Pioneers, and the Felix Foundation for all the work that he and his group have done together in California's mining history. The Nevada County Historical Society that he leads is vital to what we do here and across the whole county. And interestingly for me, he's a reader at the Huntington Library in San Marino and since I used to live in Pasadena and San Marino was just right there, I went many times to the Huntington Library. And many of the archives regarding mining and the North Star House, the foot family, the whole history of the North Star House, a lot of that is at the Huntington Library. And so we really want to have a good association with them. So without further ado, Gage, let us know all about it. Thank you. Thank you everyone for being here this afternoon. Do you like the sound of that? Yes. Good. Great. Great. So I was on the radio with my friend Tom Simmons on KNCO this week and Tom said, you know, the more you talk about history, Gage, the younger you get. And so I'm hoping by the end of this afternoon, I'm going to be 50 again. Well, we are very just thrilled to have the Hague family with us and I'm going to introduce them in a little while. But first, launch into the story of their illustrious ancestor, James D. Hague. And so, well, to help everybody feel younger, let's start with the pop quiz. So there are two questions. And if you know the answer to the first one, I want you to just raise your hand, but keep your hand up. So who lived in this house, drew illustrations for magazines and books, wrote stories for century and other national publications, and wrote books about the American West. Who knows the answer? Does everybody know? Somebody say it out. Mary Halleck. Mary Halleck foot. And who else? No, Arthur did not illustrate and write. Who else? James Hague. James D. Hague. James D. Hague wrote, was a writer for Overland Monthly, the Century National Geographic. His illustrations were in books about mining and in National Geographic magazines, and he wrote a couple of books about the American West, one called Mining Industries. So I have described him elsewhere as the Forgotten Man in Grass Valley, because he is the person responsible for the North Star Powerhouse, which is now this great engineering and cultural museum, one of the great in the West, and this North Star House. And by responsible, I mean, he selected the sites, he got the resources in place, he got the architect and the contractor in place. So these are very much his creations. So I want to come back a little later and talk specifically about the history of the North Star Powerhouse and the North Star Cottage first and then the North Star House. But let's begin with James D. Hague. So he's not a gold rush figure. He was born in 1836, and when James Marshall, about 50 miles from here, discovered gold on the American River, James Hague was an 11-year-old boy, and his principal interest in January 1848 was skating on Jamaica Pond in Boston. And so he did not get to Grass Valley until much later. He went to Harvard, and Harvard had recently opened its, what it called, its scientific schools. So what had been a liberal arts education now had a scientific dimension to it. And so he got a very good grounding in chemistry at Harvard, and then he went to Europe and took up his studies in Hanover, Germany, at the University of Sayedelke. Göttingen. Göttingen. Göttingen. Göttingen. Göttingen. She says it right. And so he was there for a couple of years, and that university started by, founded by George I of England, who was the elector of Hanover, that university was known for accommodating English speakers, especially British students and American students. The whole line of famous Americans went there, including Longfellow and Bancroft and many others. And when Hague was there, he especially studied mathematics, and one of his classmates was a mathematic whiz named J. P. Morgan. And Mr. Hague and Mr. Morgan were lifelong friends after that. And that theme, lifelong friends, James D. Hague was great at making friends, great at keeping friends, and most of his friends became lifelong friends. And so after some time becoming proficient in the German language, he went on to the oldest technical university in the world. That's the Royal School of Mines at Freiberg, Germany, in Saxony. And it's a school of mines actually built on top of the ancient lead and silver mines of Saxony, so that it was a theoretical education in the classroom, that it was also a practical education because the miners there were very proud of the fact that they helped to educate the students and took them underground and taught them practical mining. And so at Freiberg, my wife and I have been there to visit the university, and don't think of a western mining town, no swinging door saloons, no makeshift shanties. No, they have castles and monuments and statues, but the expression on the street, even to this day, is still when people greet you on the street, they say, Click off. Click off, like she said it. You know, I'm a Germanophile, and if you really want to do that right, you need to have a native speaker in the home. And so it would be as if we greeted people on the street of Grass Valley saying, Howdy-Pard, it would carry about the same sort of cultural weight. And so while there, of course, Mr. Haig's family were as much European as they were American, he descended from Scottish sea captains and clergymen, and Europe was never far away. His father, who was a very prominent Protestant clergyman in Boston, had gone to England, well, he had gone to England and Europe as part of his education, and of course Mr. Haig and his family, rather like characters in a Henry James novel, traveled to England many times during their lifetimes. His daughters could have substituted for Daisy Miller in the famous Henry James short stories, though perhaps they were a little better behaved than Daisy Miller. And so after his time at Freiburg, he was there with other American students. And so he had an American roommate, Louis Genine, and he set up a chemistry, and these were serious students, and they felt the chemistry at Freiburg was a little deficient. And so they set up their own chemistry lab in their digs at Freiburg, and then they had a lot of opportunity to travel around Europe. Of course they went on field trips to the Alps and other high places as far as their, as part of their training at Freiburg, but they had a lot of opportunity to see Dresden, which was nearby, but Munich and Vienna and Paris and the capitals of Paris. So when Mr. Haig got back to America, there's a whole South Seas episode, which is a lot of fun, but I'm going to glide over that for now and come back to it as he himself returned to the South Seas throughout his life, and talk about his first mining experience. So when he got back to the States, he did some time served in the Civil War. He was in the U. S. Navy, and then wisely, much of the naval activity between the Union, the American Navy, of course, and the Confederacy was over relatively early in the war. So the War Department, being wise people, recognized Mr. Haig was a lot more valuable to them as a miner, because they needed metals to prosecute the war than he was as a sailor. And so he was on the upper peninsula of Michigan on the St. Just Peninsula, and I'm sorry, the Kiwi Nile. St. Just is in Cornwall. In my mind, everything gets a little mixed up with Cornwall. He was on the Kiwi Nile Peninsula with sticks into Lake Superior, and he was part of, he was the geologist and the authority in discovering this great load of copper on the Kiwi Nile Peninsula. And he didn't discover it himself, but being a trained geologist, he could document it and describe it. And so he took this investment opportunity to men he knew in Boston, probably men in his father's church, or men that his father knew, and took them this investment opportunity for this great copper load in Michigan. And he was in his late 20s, and they looked him up and down, and they said, oh, young man, probably not. They didn't invest. And so that load became, in just a few years, the Hecula Calumet mine, which was in its day the greatest copper mine in America, and produced something like a quarter of the copper in the world. And those Boston investors who had this softball pitch to them and they whiffed, they never forgot James Hague. And that was the beginning of this relationship that he built with money people, J. P. Morgan, one of them, many others, the Bliss family, the Thelps Dodge people, the Anaconda people, many famous people in mining. That was the beginning of building a relationship of trust with those kinds of investors. So having had this great success in Michigan, he might have thought, well, my career as a mining consultant is launched. And I can just go off and reap the harvest. But he didn't do that. He wanted to learn more about the American West. And he had an ideal in his mind, an ideal of what a scientist was. And it's different from the way we think of science or scientists. To him and to his generation, a scientist was not a white coat in the lab. A scientist was an explorer on the edge of the known world. And the model for that was a German, Alexander von Humboldt. And so if you want to know where Humboldt County comes from and Humboldt Mountain and all the hundreds of other Humboldts in this country, they're all named after Alexander von Humboldt. And before Darwin, if you ask anyone, maybe if you ask anyone today, name a scientist. And they'd say, well, Darwin, Einstein, or Hawking. In Hague State, name a scientist, von Humboldt. And just to prove it, the chocolate company in Vienna stamped his image on chocolates and shipped it all around the world. So Mr. Hague, for a nominal salary, joined an effort to survey the 40th parallel from the Sierra Nevadas eastward towards the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. And so the 40th parallel vaguely was the route of the transcontinental railroad. And their project was vaguely, 100 miles either side of the 40th parallel, to document the flora and the fauna and all the features of this landscape that was about to be opened up by the railroad. So Congress financed this. There was no U. S. geological survey at that time. Not yet. It was conducted, financed through the War Department. But the 40th parallel survey was all civilians. Mr. Hague was a Harvard man, but he got along real well with Yalees. He was mostly Yale men, led by a man named Clarence King, again, all lifelong friends of Hague's. And what Congress was really interested in was flora, fauna, that's interesting. They wanted to know about the mineral resources. And so the project eventually published seven volumes and oversized atlas. And it redefined how to do a geological survey and how to do an atlas. Because they drew maps, actually, the way that we draw them today. And so a lot of geological surveys go back to that effort. But what Congress really wanted to know was about these mineral resources. So Mr. Hague was the geologist, the head geologist on the project, although Clarence King was a great geologist too. And he was responsible for the volume on mining. And so it was the third volume in the seven, right? But it was published first because they knew that's what Congress wanted to see. And for future appropriations, they had to present the mining material first. And so Mr. Hague did this survey of the American West. Still the historic, the history of Virginia City, Nevada, and the mining there. It's all based upon work that Mr. Hague and his team did in about 1870. So as the railroad was being built. And all of the mining districts of Nevada and Idaho and some in Colorado. And so that opened up the mining West. And so his book became a textbook in engineering courses in the United States. So that really launched him. And so he then really began his career as a consulting engineer. And mining engineer, then somewhat now, but then especially anyone who worked around a mine. Especially if they had an education. And Mr. Hague had the best in the world. It was called a mining engineer. If we described what James Hague did today, we would call him an economic geologist. And so he really understood the geology. And from that time in Germany, and he understood economics and could really do the math and work out the figures. And so there is more gold in the ground here today than there ever was. Ever was taken out under this mine, under the adjoining mines running east of here. There are $350 billion of rare earth metals we understand in Ukraine. Those are kind of interesting facts to an economic geologist. The fact they're looking for is, can you get those metals out of the mine and make a profit? Are they economically viable? That's the real question. And that's the question that James Hague set for his life's work answering for investors. And so he initially, some of his earliest investors were from London and York, England. And one of the early investments he led them into was a property called the Pittsburgh Mine. Does anyone know where that is? The Pittsburgh Mine? Yeah, it's over here about three miles. It's in the area of town talk above Tunnel Road around Banner Mountain Road. That was the Pittsburgh Mine. It never made a whole lot of money, but it was very characteristic of Hague's investments in that the geology was solid. The precious metals were there. The mine was well managed. And so while it was never a bonanza like the North Star, the Empire, the Idaho, Maryland, it was always profitable. And those British investors were involved in that mine for over 50 years. And they eventually sold out to friends of mine, the local family sold out the property. So that's the kind of investment that James Hague did. And so he had a, I'm just looking at the time here. Oh, great. And he had a lot more youth to develop. And so he had a successful mine with Clarence King, his good, really close friend, Clarence King, in Placerville, near Placerville. That was a successful operation. And a lot of other modest successes in Nevada and in Silver City, New Mexico, where Elka and I had a really great week chasing down Mr. Hague's investments there. And Silver City is interesting. Just what was the life of an itinerant consulting engineer? So Mr. Hague went down to Silver City about 1878. And so his first trip, the Santa Fe Railroad was starting to open up the Southwest. And so you could get from Chicago to Albuquerque and then a little further south to Socorro on the railroad. And then it was a 400 mile ride on stagecoach, which was not very pleasant. And so all the way down to the south end of the state, to the Gila Mountains and Minbrainos River, where he had a silver mine. And so in the course of the next five years, and this is how fast the West was being developed, within a year, the railroad was now coming across the bottom of the country and he could get to Las Cruces. And then a much shorter stagecoach ride and a year after that a narrow gauge railroad from Las Cruces into Silver City. And hardly any, well, he had another 25 miles of stage to get to his mind. But Mr. Hague was part of developing the West and the first industry, it's mining, it's always mining. That's what opens things up, brings in other industries, brings in workers, skilled workers and engineering talent. And so he was part of this opening of the American West and that really was his life's work. So he came here, he visited this mining property just actually before he got in the Civil War. And he was just a tourist with some friends from Freiburg. He was coming back from Honolulu and they met in San Francisco and came up here as tourists to see these mines. And he saw the Gold Hill Mine, he met Melville Atwood, who was the great director of mines here. An assayist who assayed the Silver Discovery from Virginia City. And he did some work around here, he did some work with the hydraulic mining. And he was obviously conflicted about hydraulic mining because obviously the environmental disaster that it was. And in his own notes he described that kind of environmental damage. He's one of the few people I've run into who contemporarily ever described hydraulic mining in environmental terms or ecological terms. It goes back to Humboldt, that's his German scientific training. Because most people in that day describe it purely in economic terms. And did the economic benefits to the miners outweigh the economic detriments to the farmers downriver. That's how most people talked about it. So Mr. Hague's reports about hydraulic mining were actually used by Judge Sawyer when he in, someone help me with the date 1874? 1885. 1885? Okay, okay. The high bidder 1885 when Judge Sawyer essentially shut down hydraulic mining. And in Judge Sawyer's decision are whole paragraphs quoted from James D. Hague. So he had a lot of experience around this area. But what got him to this mine was when he was working down in the mother mode. So that's that country down south, down south of the American River. And in shingle springs, in an inn, he ran into the most interesting young man who was about 12, 14 years younger than he was, William Bourne. William Bourne Jr. And they were in the inn that night. And I can just imagine how James Hague got an earful from William Bourne about what he was doing at the empire mine. And, but more especially when they met, William Bourne had just bought the North Star, which had been out of operation for about 15 years. And he bought it to flip it. He bought the North Star out of operation and he was going to get it operating, get the bumps working, bring up some more and put a coat of paint on everything. The paint was green and then sell it to someone. And what Bourne really needed was an economic geologist. And so he persuaded Mr. Hague to come to Grass Valley to work for him as a consultant. Now it wasn't easy. Hague was very resistant to coming. And the reason was there was a young man here already working for Bourne, a very proud young man, about even younger than Bourne. So almost a generation younger than Hague himself, who had also graduated from Freiburg named John Hay Hammond. And I think what happened, I think what was in Mr. Hague's mind, he didn't want to have two consultants and then be in conflict. And giving conflicting information to young Mr. Bourne. But Bourne, I can just imagine how William Bourne, who was known for being, should we say forceful in his business dealings, how he persuaded Hammond to write and invite Hague. And Hague kind of saw through that. But he eventually did come. And so the three of them worked on the geology of this mine. And they were down underground in this mine every day. This mine, I mean the North Star. And trying to figure out the geology and figuring out the value of the ore and what it would take to make this mine successful. And I sensed there was quite a bit of tension between Hague and Hammond. Now, it wasn't easy to have tension with James Hague. He could diffuse any problem or any tension. He was a very charming man and a gracious gentleman. Hammond was younger and sort of had something to prove. But a remark that William Bourne let slip 20 years later about Hague and Hammond and all their thunder sort of suggests that there are some tense conversations. And so what you need to understand, to understand a remark I'm going to make, is that in California, this region, the host rock of gold is quartz. And so the earth tilts, the granite pushes up, and then the quartz pushes up in the cracks in the granite, and the gold is in the quartz. And so they would be all day underground and then in the evening talking about what they'd seen and debating where the gold lay and how best to pursue it. And so Mr. Hague described this as quartz by day and pints by night. And listening to all this in the room with them, probably with his own pints, was a young man named George Starr who was William Bourne's younger cousin and would eventually be the general manager and managing director of the Empire Mine. And this was where George Starr got some of his education that made him the mining genius that he became. And he eventually worked for Mr. Hague for a time. Well, James Hague became so intrigued with the North Star Mine that he, like, couldn't keep away from this part. And he'd lived most of his life in New York City, but he would be here for months at a time and sometimes for six months out of the year, routinely for at least three months a year, he would be here. And he built a house for his mine managers, a little down the slope, you can see the foundation of it, and that was the North Star Cottage. And Mr. Hague built that, and that's where he had quarters and the mine manager and managers family. And so during this period, during the late 1880s, William Bourne got very involved in the wine business in Napa Valley and became a big leader of that. And then his mother's estate at St. Helena burnt down, and so he needed cash. So Mr. Bourne sold the Empire Mine, the controlling interest in the Empire Mine to James Hague. And James Hague had that for seven or eight years. And then he eventually, he sold it back to Bourne because he was so engaged here. And this took all his energy and all his commitment and running both mines is really too much. And typical William Bourne deal, William Bourne sold high and he bought low. And a lot of mining people thought he took advantage of his friendship with Hague and of Hague's connection with especially Eastern investors. But James Hague was a great friend and William Bourne's best friend. And he never complained and he never had an unkind word or critical word to say about his friend William Bourne's. So Hague was really involved here with the North Star Mine. He's still traveling all over the country. He's on the railroad constantly. He knows all the porters by name because he's still a consulting engineer. And that's a very lucrative career in itself. And then he was the majority owner of this mine. And so let's talk about the powerhouse and this house. So the economic geologist that he was, he knew what this mine really needed was three things. It needed to be bigger, a much bigger property. So it could be managed on an economic scale to get the advantages of scale. And so he spent 12 years acquiring the property that he wanted. And so the North Star Mine, the original opening or what's the inclined shaft is, anyone shout out and correct me if you've got a better figure? But about a quarter of a mile down the road. And then it runs north towards Grass Valley. So what Mr. Hague did was to acquire this whole mineral rise region. There are all these little mines. There's a list of them in the book, Rocky Hill Mine. I'm not coming up with names. Somebody shout them out, Jerry. Boston Ravine Mine, maybe Gold Hill Mine, so forth. He acquired all these mines. Now of course you want to do this quietly. You don't want people to know you're acquiring all this property. Here it drives up the price. And so he did this as quietly as he could for a few years with the help of his friend, William Bourne, who was kind of in on the deal. And then eventually the cat was out of the bag and he was involved in lawsuits with some of these mines and different things. But he acquired this mineralized region from a quarter of a mile south of here to over a mile and a half north of here. So people who live locally, if you know where the Gold Hill Monument is, well he owned the land, he owned the mineral rights under that going into Grass Valley. So I tell people, little exaggeration, almost as St. Patrick's Church. And so that was the region. So he needed that. He acquired it over about 12 years. He needed an inexpensive source of power to drive the equipment. And he needed the kind of power. You know, mining began here with what the Cornish called double jacking. And so you have a steel drill and you pound it into the face of the granite with hammers, with sledges. And to create your holes and you set your dynamite and blast the rock out. Double jacking was the preferred way. And double jacking, I think it was how many two people and how many blows a minute? Somebody knows. 50 blows a minute and 50 blows a minute. And that's men working hard to do it. Bringing a pneumatic drill. And that was. . . 1600 blows a minute. 1600 blows a minute. Thank you, Orlo. 1600 blows a minute. So and one man on the machine. And so you need it in source of power. And so about 1889. Mr. Hague had this all thought out in his mind. And he had selected the place for what we know today is the North Star powerhouse. He, on the land, he had selected the site. He wrote it all down in a notebook, described the powerhouse in a notebook. In 1891, in 1893, he revealed it all in a written report to his investors, who were San Francisco, New York, a few Boston people. He revealed it to his investors. And in 1895, he hired the best engineer he knew, happened to be his brother-in-law, Arthur D. Foot, to come build it. And so that's how the powerhouse came to be built. Now, before they built it, Mr. Hague sent Mr. Foot around the country, of course on expense accounts, and to look at electrical plants. One in Riverside, California. But the one they were really interested in was the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, back at the Hanglet Calumet mine. This hugely successful copper mine. And they were putting it in an electrical plant. And Arthur Foot went back there and looked at it, and he didn't like it. He felt electricity at that stage was not sufficiently developed as a technology to be used underground in mines in wet circumstances. It was a danger to the men. And so what he wanted to put in was a compressed air plant. And so there was a battle over this. And James Hague for electricity, Arthur Foot for compressed air. And it was a battle going on industry-wide. Their own discussions and arguments reflected what was going on in the mining industry across the country. Well, this is how James Hague managed men. He was an excellent manager. And he had done this earlier with George Starr. He'd let his manager argue with him, debate with him, and so forth. And at some point he would finally say, OK, you win. And the responsibility for success is on you. And so he put the burden on Arthur Foot. And Arthur Foot designed a compressed air plant that from, you know, down at the Wolf Creek where the powerhouse is and brought hot air up here at 95% efficiency. And it drove all those pneumatic drills. It drove machinery. And it even warmed the dry house where the miners changed their clothes. And so it was a huge success. And part of the success, and Jeffrey and George and the other volunteers will show you the 30-foot pelton wheel that Arthur Foot created to maximize the power that they could generate. And so one other element that Mr. Hague needed, and that was he wanted a vertical shaft. So you have this long inclined shaft heading from here up towards Grass Valley. And he said to really open up this whole mineralized region and operate efficiently, you need a vertical shaft because in mining you want to dig the shaft out and then always be working up. So the ore is falling so that gravity is on your side. And so right up above the house here is what became known as the central shaft. And it's about 1,600 feet deep where it connects to the inclined empire shaft. And it opened up this whole region for economic mining. And it took all these years to put these elements in place, so much patience, so much perseverance, so much time cramped into the empire cottage where the Foot family eventually lived there. And by 1893 the mine was making a profit. Now it had made a profit periodically, intermittently, all the years Hague had it because he managed it well. And he needed to show profit to keep his investors on board. But he always told them, he wrote to them, he humored and conjoaled his investors. And you have what's going to be one of the great mining properties in the world. Just stick with it. And because it was James Hague saying this, they stuck with him. Morgan and Phelps Dodds and Bliss and all of the others, they stuck with him. And he saw in 1893 not only was the mine making a profit, but it was making the right kind of profit. That is, it was making profit based upon the deep bones of this mine and the economic realities of what it took to operate it efficiently. And so this mine went on to be highly profitable for the rest of Mr. Hague's lifetime. And of course it went on to employ men up until 1956, hundreds of jobs because of what the foundation that Mr. Hague laid here. And so with that profit coming in and he realized it was coming in for years to come, he needed a bigger house. When he came here, spent three months or something, they remodeled the cottage so he'd have a bigger bedroom. He was president of the company. And Arthur Foote, if Mr. Hague brought someone with him, a mining engineer, an investor, someone to show the property, Arthur Foote had to move out of the house, give up his bedroom, and he slipped under a tent. And Mary Hallock Foote moved in with one of her daughters. And so they needed a bigger house. So in 1893 when he came, about this time of year, for several months, he came, he got off the narrow-gauge railroad, he came over to this property and he walked the ground and he picked this site. This is a site for the house. And then he showed it to Arthur Foote and then he showed it to Mary Foote. And said, this is where we're going to build the house with its beautiful westward vista. And so he was very socially connected, part of social register in New York, but he had a great lot of friends in San Francisco because he lived there for seven years early in his career. And among his close social circle in San Francisco were Benjamin Ida Wheeler, who was the president of the University of California, and Dean Samuel Christie, who was the dean of the Hearst School of Mines at UC Berkeley, which became one of the great mining schools in the world, based upon the Freiburg model and trying to rival Freiburg with their own model. And so he went down and spent time in San Francisco, had an intimate dinner with these UC Berkeley people and another lifelong friend, Emily Ashburner, who was an important, maybe the important benefactor to the UC Berkeley campus before Mrs. Hearst. And I presume that's where he heard about a young woman architect working on the campus, working on the Hearst mining building, which was Mrs. Hearst's first gift to the campus, named Julia Morgan. And so on a subsequent visit to the Bay Area, he had lunch with Dean Christie in Berkeley, and they walked down to look at the new mining building. That could have been when he met Julia Morgan. I don't know. Mr. Hayd kept a pocket diary, and at the end of the day he jot things down that had happened during the day, and you think, well, you met Julia Morgan, you write that down. Well, it's not in the diary, but I'll tell you this about the diary. The day he had lunch with Charles Darwin in London, that's not in the diary either. So later when he stayed at Charles Darwin's home, which is a place Ilka and I went to do research, a wonderful place to visit in Kent, England, that got in the diary, but just a lunch with Darwin didn't quite break it. So Julia Morgan at some point was hired. Now here's a really intriguing thing. In 1903, he certainly knew about her. He may have come to some understanding with her, because he immediately returned to that trip to Berkeley, and he and Arthur began drawing preliminary plans for a house on this site. And so that suggests to me, he talked to someone who said, well, why don't you draw something up and give me an idea of what you have in mind. And so they immediately began drawing some sketches for this house. Mary Hallock Foot was perturbed because the men were down in the cottage after dinner with their sleeves rolled up, drawing sketches and so forth, and she was not consulted. I can assure you when Julia Morgan got on the job, that was rectified. Because Julia Morgan was famous for making sure the women had a voice in how projects were constructed. So now a year elapses before Julia Morgan comes here, and so it raises this intriguing possibility. Miss Morgan's papers from the era we're talking about were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. So no one has found a contract for her, and she certainly had one. And what I found in the North Star Mining Company papers, if you want to spend a casual afternoon reading through some of the 55 boxes, they're at the Beinecke Library at Yale. So that's where Bilka and I spent a week, and we recommend the Graduate Hotel, and I do spend all day on campus every day going through the papers. And what I found were letters between Arthur Foot and Arthur Foot's son, Arthur B. Foot and Julia Morgan, and letters from Julia Morgan, but no other details. But she finished the drawings about October. The details are in the book, if I get them a little bit off, about October of 1904. So presumably she was up here in the summer of 1904 to walk the property, and so it leaves this really intriguing possibility. She didn't get licensed as an architect until 1904. So in 1903 she was still working under a licensed architect, John Galen Howard, as a Berkeley person I have to bow, who built the UC campus. And so she was working under his auspices. So it's possible Mr. Hague held out building this house until Julia was available to come do the job. So they began building in 1904, typical of Hague. He picked the site, had the big picture, had the concept, which he had written out and so forth, did some preliminary drawings, and then turned it over to Morgan and the Foot's and said, build the house. And as Mary Hallett Foot said, the mining company did not build this house over our heads, but let us do it. And she was very grateful for that. And of course she has her own office in the house. So this house has always been a place of hospitality and creativity. And you can look at the work the volunteers are doing here, and you'll see the hospitality in a bit and know that that's what it still is. And so Mr. Hague made a lot of money here, and a lot of other people rich, employed Grass Valley families for generations in this mine and encouraged others, including Arrow McBoyle at the Idaho-Marilyn mine, which employed thousands of men, especially during the Great Depression in the 1930s. So it was all on the foundations that Mr. Hague laid with that great understanding he had of the principles, geology, economics, and his faith in God, which is a big part of the book too. So, you know, the people here at North Star have just been wonderful in putting on this event. Haley Wright, the manager, is just a dream to work with and such a wonderful person. And so I'm very grateful to the North Star House and the Board of Directors and all of the volunteers who have saved this house. The special people we have here today are three generations of the Hague family. And so I'd like them to stand up, and I'd like to introduce, they'll be right to left, Horner Davis and Bill Hague, you might turn around. And Daniel Hague, Patricia Hague, and Luca Hague. And so this is of Jane Hague, this is the great grandson, great, great, great, great. One more. And Bill Hague, excuse me, I got that, the Reverend Dr. William Hague. Bill Hague lived in the Hague house when he was a boy, when the Hague family still had that part of the property. As you know, the foot family, of course, Arthur and Mary Halleck never owned this house. This house was a corporate asset, it was owned by the North Star mine. But their son, when Newmont Mining Company came to Grass Valley and consolidated the empire in North Star, their son, Arthur B. Foot, sometimes known as Sonny, by those of us who love him, he and his wife, Jeanette, bought this house. And then the foot family owned it after about 1930, and then it went on to, well, to a troubled career, but resulting in this beautiful house that's here today. So I want to say to all of you, thank you so much for coming out on this beautiful spring day. Angie and the bookseller staff have books to sell inside, and maybe my books will make you younger. So take them home and try it. And I thank the Hague family for the hospitality that we're about to enjoy. Yes. Is there a mic for Bill? Thank you. This is such an honor, and Gage is the most amazing person to make my family come alive. I think that your title of the forgotten person is no longer forgotten. And what would you do if you got a call just out of the blue from a total stranger who said, I'm interested in your family. May I talk to you a bit? And so I got on the phone, met Gage McKinney, lifelong friendship. The stories are fantastic in the book. And the best part of the book for me was that my father told me most of these stories at the dining room table. And I passed them on to my sons, and nobody believed me. And if you read the book, you'll be equally astonished, and you might be even a bit skeptical as my sons are. But the stories from, for example, that my father would say, did you know that Papa, as he was known in our family, persuaded Teddy Roosevelt to give him a worship, to explore a South Sea island? That's a great story in the book. It's well worth getting the book today. In the book, and in the slideshow that Gage put together so beautifully, there is an object that we would like to give to Gage. Excuse me. Sorry for being emotional, but this is so much. So I grew up with this bill, which was given by the Bourne family to Papa, James Hay. I'll let you open it up, because you don't know exactly what it is. Do you want to describe it? When James Hay was negotiating to buy the North Star Mine, he stayed through Christmas in California. He was invited to St. Helena by Sarah Bourne for Christmas. There were, I believe, 17 people for dinner at Mrs. Bourne's estate, and each of them, Christmas 1886, got a silver bell engraved as a memory of that Christmas. Bill, thank you so much. This is priceless. It's also served as a place card. It's written Mr. Hay, so he knew where to sit. In our household growing up, we used that bell. My parents built a house down in Pebble Beach, and they had a. . . Did any of you grow up with buzzers underneath the table so that you'd push the buzzer and would announce the end of a course and bring on the next course? Well, the buzzer was way over here, and so the dog kept sitting on it. And so we used this bell every night for dinner, and that would signal the next course. But Bill, please use this bell when you're ready for Gaze to Clean Eye. Can I ask a question? Sure. Can you give us a little bit of information on the Hague house when it was built and whether. . . Yes, right. Which Hague's were involved with it? So Bill's grandfather, also William Hague, was known around the mines and elsewhere, socially, as Billy Hague. And he followed his father into mine engineering and worked at various mines in the American West. Like his father, got a really good, after Harvard, got a very good practical education traveling among the mines. And so James Hague died in 1908, and Arthur Hague's senior retired in 1912. So after that, the North Star was managed by a team. And the team was Billy Hague, who was the managing director, and reported directly to the board of directors back in New York City. They had their office on Wall Street. And the younger foot, Sonny Foot, was the manager of the mine. And they were, of course, first cousins, but also an excellent management team. And they divided up the labor, and Billy, like his father, was really good with the numbers, close with the economics, and wanted the mine running efficiently, and Sonny managed it well, managed the men well, as his father did. And so they were highly successful. And so when Billy Hague married a beautiful woman from New England, and so he hired a New England architect, I think possibly a Harvard classmate, to design a house here. And so it was built around 1912, I think. Someone probably has the right date. It's in the book. And so Billy Hague and his wife and then their two sons lived in the house. Part of the reason that James Hague is a forgotten man here, and it's not on the plaques outside the powerhouse and this house and so forth, is because Billy, he didn't have to. He did it out of patriotism, but he was a trained engineer and the army needed engineers in World War I. And he was the first contingent that went to France to build all the harbor facilities at Harvard, which was our harbor, which was the western port set aside for all the American goods to come in. And sadly, it was the coldest winter Europe had in 50 years. The Americans were unprepared for it. Billy caught pneumonia and died in the hospital in Paris in January of 1917. My father was actually born in the house, 1911. 1911. And so was his brother, Nathaniel. And my nephew is named Nathaniel. Nathaniel. So Bill's father, just to keep them straight, I call Commander Hague, because he had a career in the amazing career in the U. S. Navy in WWII. Commander Hague was born in the house in 1911. He was also a James D. Hague and his brother, Nathaniel. If there's another question, shout it out. Otherwise we'll. . . Yeah, just shout it out. Yes. Angle of her pose. Yes. Wealth of things. Yes. Full of surprise when you look. Yes. Regarding the footpelling, particularly has to do with Mary Hallock foot. It does. It went to court because of libel, I guess, and false impressions regarding Mary Hallock foot. Can you speak to that? So, false impressions regarding Mary Hallock foot, yes. Regrettably in abundance late in the book, especially for his own narrative purposes. Stegner twists the foot story for drama. More disturbing, or also disturbing, is he lifted whole passages, great swaths of her writing, are in the book without accreditation. Never went to court. But Bill's father, Commander Hague, was responsible for the publication of Mary Hallock foot's memoirs, which are Victorian Gentle Woman in the Far West. So the foot family was literally traumatized by that book and the foots and hakes. They fought back, and the foot family used to give talk to service clubs and so forth and explain what was true and what was false in that novel. And then the publication of Victorian Gentle Woman really exposed it all. So now the context for reading Angle of Repose, this is TS Eliot's theory of literature that a new work changes the context for everything that was written previously. So now the context for Angle of Repose, you really can't understand or appreciate that book without having side by side Mary Hallock foot's own memoir in which she told her own story. And when you have them both, then you have a pretty comprehensive publication, an understanding of what Stegner did, the genius that is in the novel, but how much of that genius was not only Mr. Stegner's, but also Mrs. Foot's. It never went to court. It never went to court. Did Stegner apologize? No. I actually have a certain sympathy for Stegner, and I hope to write about that, but a man so gifted in language in this pickle that he got himself into, never found the language to get out of it, never really found a way out. And so it was always trouble. I mean, it was troubling to him. It was troubling to everyone around for the rest of their lives. Hey, Gage. Yes, Jeffrey. Jeffrey Boyle here, director of the North Star Mindpower House Museum, which is a huge part of the story. Indeed. On behalf of everyone here, Gage, I want to thank you for being you and keeping these stories alive, and it's a lot better than reading Wikipedia. You're just such a treasured community through your books. You've just painted such great pictures of our local stories. I don't know of another community that can claim that sort of thing, and you're so precious to all of us. I know. So thank you very much. Thank you very much. Thank you very much, Jeffrey. And thank you all for keeping that powerhouse alive. And some of the longtime volunteers of that powerhouse, they're no longer with us, but members of the foot family. Which is a really great legacy of that powerhouse. Bill's father had a big part to play in that powerhouse. So if there's another question, shout it out, or come see me afterwards. And otherwise, someone will probably give us further instructions.