Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2025-04-17 - American Burial Ground - A New History of the Overland Trail with Sarah Keyes (61 minutes)

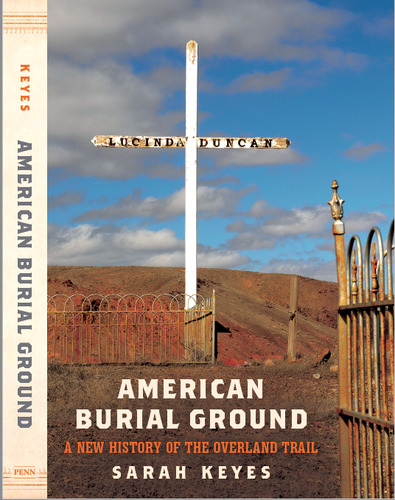

Historian Sarah Keyes discusses her book, American Burial Ground: A New History of the Overland Trail. American Burial Ground places death at the center of the history of the Overland Trail and, in doing so, offers a sweeping and long overdue reinterpretation of this historic touchstone. Keyes discusses how emigrant graves became seeds of U.S. possession across the West and how Native peoples defended their homelands by pointing to their graves as proofs of Indigenous persistence and enduring territorial claims.

Sarah Keyes is a historian of the United States. She specializes in the 19th century and the history of the U.S. West with a focus on the environment and intercultural interactions between Indigenous peoples and Euro-Americans. Her recent book, which was supported by a Donald J. Sterling Jr. Fellowship at the Oregon Historical Society, explores these topics along the overland trails to Oregon and California in the mid-19th century. Keyes has also begun work on her second project, a regional and transnational study of suffrage in the U.S. West, for which she was recently awarded a Mellon-Schlesinger Summer Research Grant from the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University.. Sarah is an Associate Professor of History, University of Reno, Nevada.

Sarah Keyes is a historian of the United States. She specializes in the 19th century and the history of the U.S. West with a focus on the environment and intercultural interactions between Indigenous peoples and Euro-Americans. Her recent book, which was supported by a Donald J. Sterling Jr. Fellowship at the Oregon Historical Society, explores these topics along the overland trails to Oregon and California in the mid-19th century. Keyes has also begun work on her second project, a regional and transnational study of suffrage in the U.S. West, for which she was recently awarded a Mellon-Schlesinger Summer Research Grant from the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University.. Sarah is an Associate Professor of History, University of Reno, Nevada.

Author: Sarah Keyes

Published: April 17, 2025

Original Held At:

Published: April 17, 2025

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

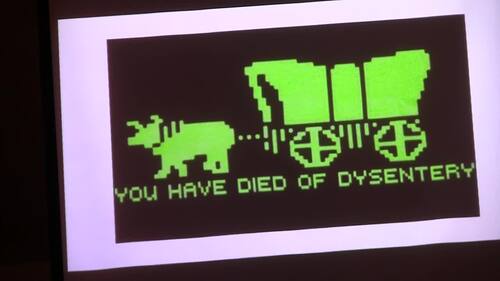

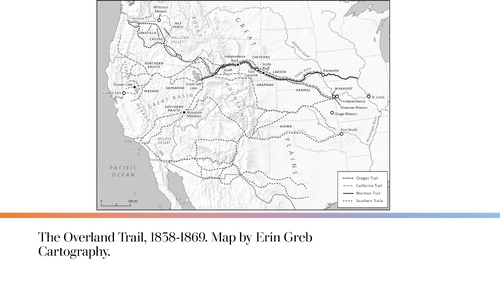

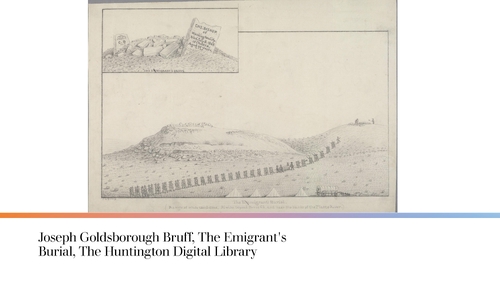

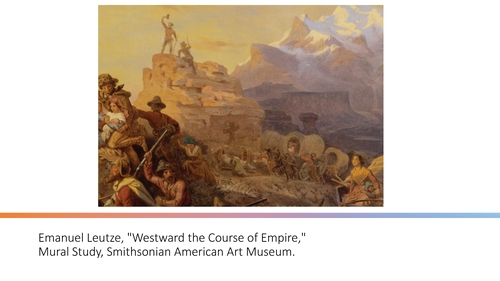

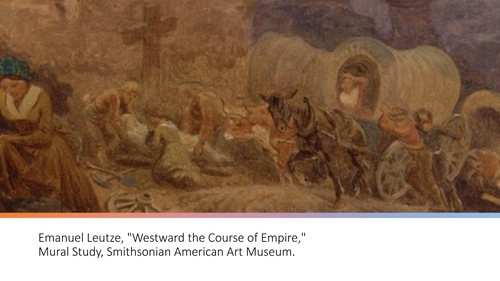

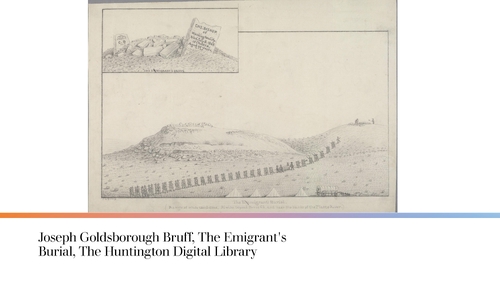

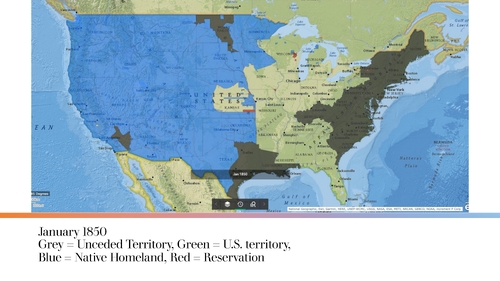

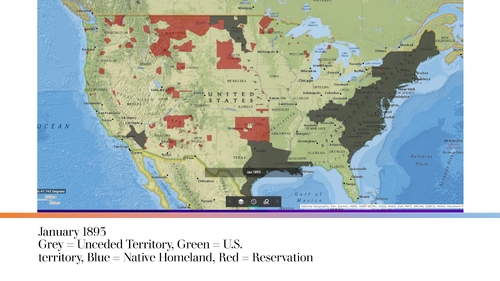

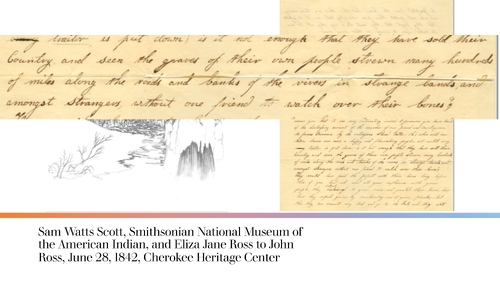

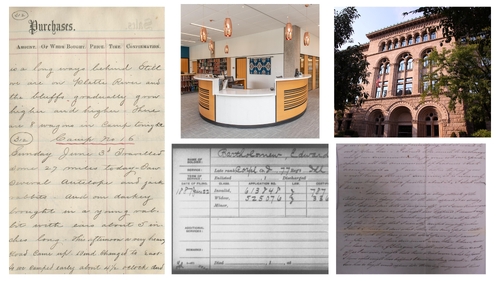

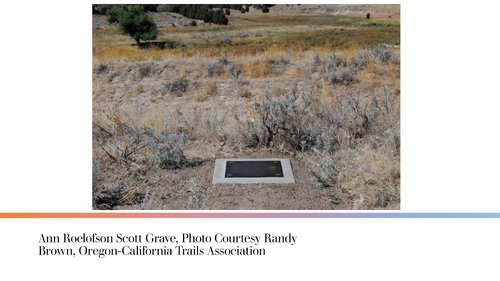

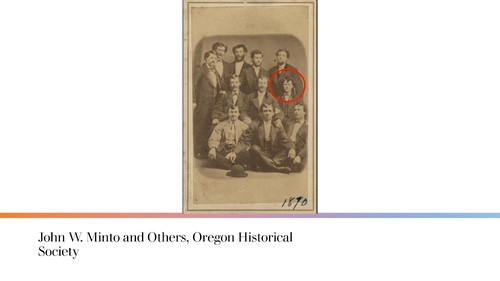

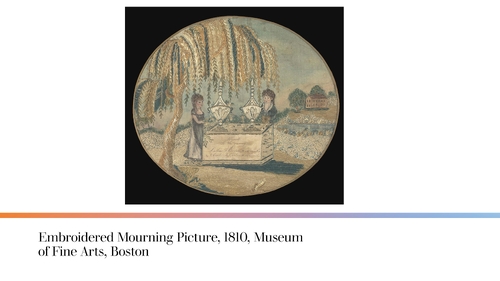

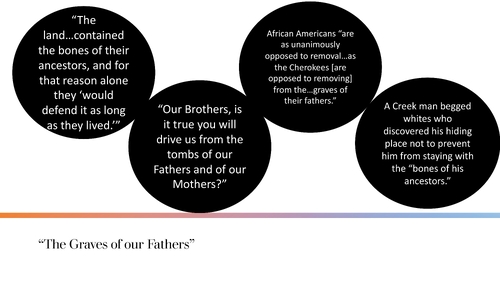

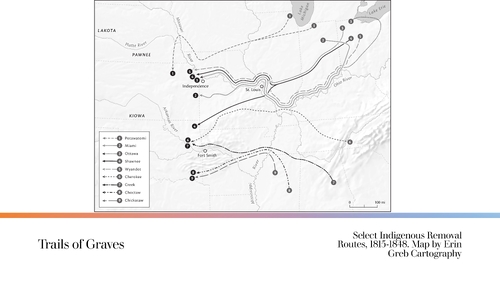

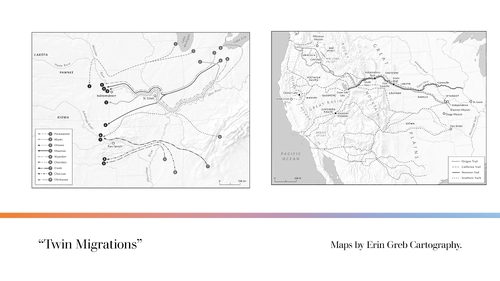

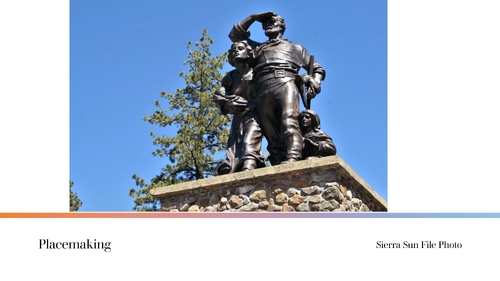

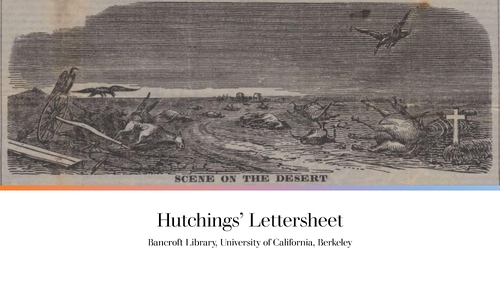

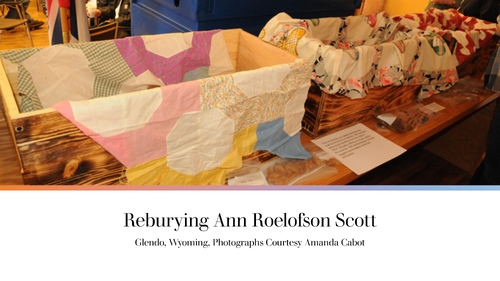

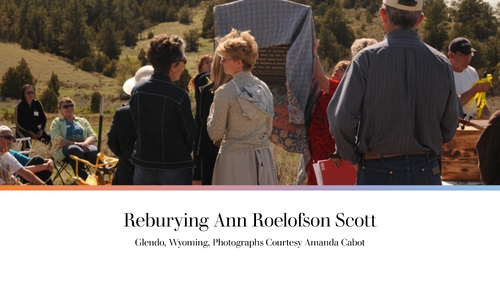

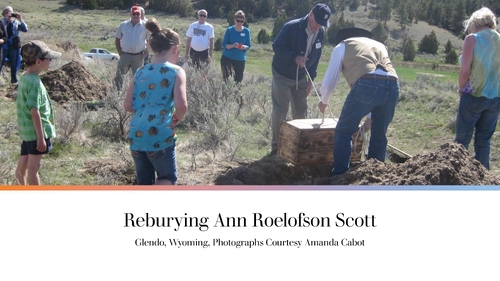

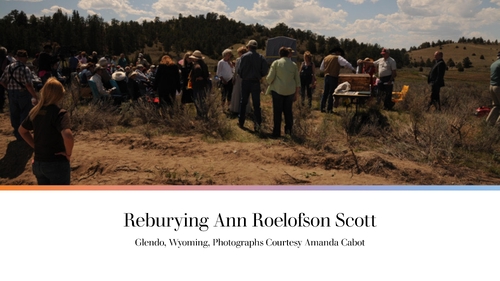

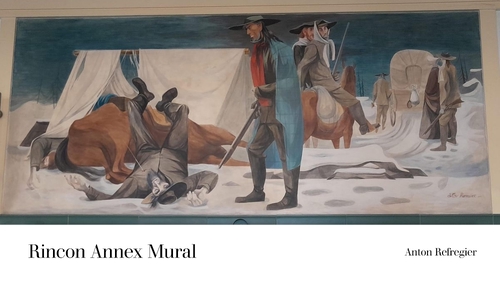

So, at this time, I'd like to introduce our presenter this evening, Sarah Keyes, who traveled Clear from Reno to be with us tonight. Appreciate that. And I'm going to let her tell a little bit about her own background and expertise and interests in history and her specialty, of course, about the old land trail and all the immigrants who traveled across the island. So, Sarah, here we go. Perfect. Well, I thank you all for coming, and I hope no one leaves after that. I'm sure we'll get it fixed. So, I talk a little. . . Are we doing okay on sound? I think we are. Okay. Okay. So, I talk a little bit about my biography and specifically my interest in the trails throughout the presentation. So, I think I'll leave that specific part and unveil it as I go along. But I'll just say that I am an associate professor of history at the University of Nevada, Reno, and that I am really thrilled to be here this evening. I'd like to thank Linda Jack for the lovely invitation. I'd like to thank Dan Ketchum for organizing and everyone else who's contributed to this event. It's a wonderful turnout, and I'm really excited to be here with all of you to talk about my new book, American Burial Ground, A New History of the Overland Trail. Now, we are in immigrant territory, right? We are in immigrant countries. So, many of you are likely familiar with the history of the Overland Trail or trails. It's an important component of local, state, and regional memory, as well as national memory. Indeed, white people moving westward and white-talked covered wagons were cinematic icons of the mid-20th century. Take, for example, the wagon train, as depicted in our old wall, which was 1930 epic wagon train film, The Big Trail. You all see John Wayne. And then from 1967, we have Andrew McLaughlin's big-budget cinematic adaptation of A. B. Guthrie Jr. 's novel, The Way West. Does anyone see this film? Okay, fantastic. So, I love this still because it captures that domesticity of the trail experience that even though men dominated, particularly during the California Gold Rush migration, the actual movement of covered wagons, culturally, is very much connected with the movement of families. And this is a really good representation of gender division of labor on the trail and the fact that women and children walked. And actually, when you think about the other half of us getting the vote in 1920, a lot of women talked about how they walked and they earned that right to citizenship through those sacrifices. Here's a more recent representation of the Overland Wagon Train in popular culture. Does anyone have any idea what this might be from? Okay, so have you all heard of Taylor Sheridan? He's been quite busy in the film sort of streaming world. He has sort of an entire corpus of very popular westerns. He's part of the surge of neo-westerns. My favorite of this TV shows is one called 1883, which is sort of the prequel to Yellowstone. Tell the story of the Dutton family and others moving overland from Texas to Montana. And I love this still because it really gets at what it might be like for somebody from the eastern limelands to get out on those great plains and then a thunderstorm comes up overhead. And you've got your white top covered wagons. Those are thin canvas covers. They're treated with a little bit, often of linseed oil for retouching. But that's not a lot. When you can get hail the size of rocks, which you all might be familiar with, that can rip right through those covers. So again, the continuation of these wagon trains in popular culture into the 21st century and for a new streaming generation. And it's not only movies. It's not only TV or streaming services. It's also computer games, right? And media. Any idea what this might be from? Is it the Oregon Trail Game? It is. It's the 2021 remake, which is. . . I don't know if anyone's played it here or if you have. I've never played it. I've seen it before. Okay, fantastic. Have you played the 2021 version? No. No? Okay, we had another hand in the back before the back. Have you? The new version? Okay. So this is really interesting. A few colleagues of mine, sort of extended colleagues who are historians of indigenous people, served as consultants for Game Lock, the company that makes these Oregon Trail games, because they said, hey, we want to make a new version. We want to bring this game to a new generation, but we want to do a better job of representing the multiplicity of people that immigrants would have encountered. So this new version only has better graphics. It has characters from a variety of backgrounds, including African-American Benjamin here, and then native characters who are more fully fleshed out when they come to trade things like salmon with immigrants. But again, it's reaching new audiences. I am more familiar with the Oregon Trail Game in this version. I don't know why the wagon looks like a paper towel roll. It was not my fault. I just played it. But this is my generation. Do you remember that one? Yes. The green and black, right? And so these are just some examples of how important the westward-moving wagon train is in American popular culture. And that cultural importance of the westward-moving wagon train is really the focus of my book and my research. And so I'd like to take just a moment to talk about that importance and meaning in relation to the physical and material migration across the continent. And a part of this I want to briefly discuss how I define Overland Trail and to explain why I use that term in my book. Because as you all know, there's a multiplicity of roots. We have a cartographic representation of them here. We have the Oregon Trail, the California Trail, the Pony Express Trail, which largely parallels the California Trail. We even have segments like the Cherokee Trail through Colorado named for Cherokee immigrants. And then we also have the southern roots that go down into Mexico or across New Mexico and then head up through southern California, right? There's a lot of pathways. And they changed over time. And when I was doing my research, I was really less interested in parsing these multiple migratory pathways across the continent and more interested in people and understanding the experiences of the people who took them and the meanings that they gave both to their landscape both to the landscape and to their journeys. And what I found in my research is that these pathways were linked in people's minds. Then and now, and we can see that now so clearly in those pop culture representations, that these pathways were linked in and now to the same monumental transcontinental migration. They're all about cresting the mountains. They're getting to that Pacific side where we are tonight. And that's really what links this migration together. And as I argue in the book, the shared trials and tragedies of these trails help to connect them. And in many ways, the entirety of the region of the U. S. West together as a landscape of white American suffering and sacrifice. Now, I have to say that I did not. I know, I couldn't resist. But this is a very serious talk, so we will also be very serious. No, I'm just kidding. Okay, I have to say that I'm not looking for the suffering and sacrifice. If you had told me, and I was raised in a very agnostic household, I'm really grateful that we're in a church tonight. It's a wonderful setting. But I was raised in a very agnostic household. If you told me that my first book would have had a cross on the cover, there's no way I would have believed you. But it does. I never thought this book would have a cross. I never thought it would be about death. But maybe I should have realized that, right? I played that Oregon Trail game, and that game is all about trying to evade death to make it to Oregon a lot. It's dysentery, drowned in a river, and it was game over. No Oregon for you, and you had to start over with a new team heading west. So of course I had this narrative in mind when I started working on the project. I mean, I was very bad at the game. I lost more times than I could count. But as I delved deep into trail documents, and I looked far and wide among other sources of the 19th century, I found something else that it wasn't game over for those who died. Instead, the deaths along the way changed the experience and the meaning of the trail for travelers and Americans at large, and they ultimately helped to advance Westward's expansion. Now, this doesn't mean these deaths weren't a loss, but they didn't mark failures. I mean, if you're migrating somewhere and you don't make it to Oregon or to California, as we're tragically seeing now around the world, we see deaths at the U. S. -Mexico border, or amongst migrants who are trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea, that's a loss. But deaths on the trail will also ultimately become something else. And they become something else because of the specific context of 19th century white Protestant culture and because of the political urge for expansion. And I share this image here to give you a sense of the work of death on the Overline Trail. We have a drawing by Joseph, a veteran known as Jay Goldsboro-Brough, one of the best-known recorders of the trail experience, and specifically of immigrant graves. And here he's showing his majority male mining company bearing and marking the grave of one of their own, of Charles Bishop. Now, I share this image with you because it's about death, and I also share it because one of the conceits of commentators and immigrants in the 19th century was that men would not be good nurses, that they would not be good caretakers, that if you died in a coal rush company on the way to California, they were just going to roll you to the side of the road and move on. But we actually see time, and again, men taking on these types of roles when they need to. And we see here, Brough's mining company doing all they can to bury and preserve the body of Charles Bishop. And so what I found in the sources is that suffering and sacrifice is at the center of the experience and the cultural narrative, the meaning of this migration. But there's been an overwhelming cultural and historical production of interpretations of the trail dating all the way back to the 19th century that have depicted the Overline migration as something else. The caravan of covered wagons transporting men, women, and children across the sunny plains. It's a triumphal, heroic, and peaceful story of party immigrants amounting obstacles, like the mountains depicted here, to reach the fertile lands of Oregon and the golden lands of California. And I love this painting by Emmanuel Lloyds. I don't know if anyone's seen it in person. It still hangs in the U. S. Capitol building today. What was a historical narrative painter? He also famously painted Washington Crossing the Delaware. And then about 10 years later in 1862, the Union government commissioned him during the Civil War to paint a picture of Westward expansion. So they're renovating the Capitol building. They're taking claim to the West as Northern space, as Union space. And they say, well, it's a Euroman. Paint us a picture of what that Westward expansion means to the nation. And so he goes West. The specific scene is likely depiction of South Pass in Wyoming, showing immigrants triumphing Westward over the Rocky Mountains. He goes West and he comes back with this. And there's a lot we could discuss about this painting. We could always return to it in the Q&A. But I actually want to draw attention to something that didn't quite make it into this painting. And it's right here. This is where it should have been, but it wasn't. It was here in the mural study, which is the last draft that Boitsa did of his final version in the Capitol. So this image gets a little bit closer to that missing piece. And then if we get a little bit closer, I hope you all can see what it is. Almost there. It was almost there. And what we're looking at here is not triumph, but suffering and sacrifice. The pain and burial and work of death. Much like Ruff recorded in his sketch from 1849. And so my point here is that while the Union government had a vested interest in depicting Westward immigration as a triumph during the Civil War, that Boitsa, like immigrants at the time, recognized its tragedies, and specifically the tragedy of dying along the way. Indeed, the trail was a treacherous, often deadly track that left a string of burials like the one in the mural study and like bishops. And with Ruff's, we can see some of the effort and strategy that goes into these burials. A procession to memorialize Bishop, the selection of a grave, not simply just by their campsite, but up on a rise. And if you put it up on a rise, that means that later immigrants are going to be able to see it. They're going to be able to pay their respects. We also see that Ruff titles us the immigrants burial. That means it's iconic. It's sort of symbolic of burials in general. But he's also careful to provide the individual identifying details of Bishop and what this inset, Charles Bishop of Washington City, died July 8th, 1849 of collar age 25 years. So he's recording that individual identity. And not only is that individual identity recorded, but all effort has gone into protecting Bishop's body buried underneath. You have the headboard, you have the footboard, and then you have additional rocks placed on top to try to keep the body preserved. And Bishop from Washington City that refers to Washington, D. C. , where Ruff's company left from, Bishop himself is very representative of the types of immigrants that would have traveled and also died during these years. Collar was the primary cause of death on the trail. And it was particularly virulent during the years of the California Gold Rush Migration. So during that 1849 to early 1850s period. But Bishop's body wasn't just a loss for Bishop. It also becomes a marker of white American space, something that later immigrants can travel to and pay their respects. Something that Bishop's family would have been interested in knowing about and remaining connected to. And so I actually, when thinking about what these immigrant deaths meant and how they played out in the 19th century, I actually was reading a book about the politics of death in 20th century Europe. And I came across a quote by a Serbian nationalist. And he's asked, you know, hey, you're saying all these things about Serbia and where Serbia is. Serbia is, okay, like tell us, where actually are Serbia's borders? And he said, do you know what? Serbia is wherever there's a Serbian grave. And he means it. And there's kind of a similar logic that goes into these 19th century burials and that undergird westward expansion in the U. S. west. And this is a darker portrait of westward expansion. But I think it gets us closer to understanding the trail than perhaps ever before. And it does so not just because it better captures the immigrant experience, but because it helps to connect the immigrant experience with the experience, the immigrant experience of expansion to the native experience of dispossession. Because how I see it, the cultural significance of the immigrant dead and laying claim to land that was inhabited by indigenous peoples is the most important argument of my book. Now, many of you are likely familiar with dispossession in U. S. history, the broken treaties and the wars that undergirded U. S. expansion to the Pacific. This map, which comes from a digital project led by historian Claudio Sont, depicts the status of native land possession in January 1850. So that's about six months after Charles Bishop was buried. And Bishop was buried between Scotts Bluff and Fort Laramie, so he would have been buried in the loop of native homeland here. And this is the state of native possession 40 years later in 1893. And the burial of Bishop's corpse in native land, and the burials of thousands of other immigrants in the lands of Little Coda, Shoshone, Northern Payu and Southern Payu, and other native polities through whose lands the trail cut, is an understudied part of this threat of dispossession. The act of inserting immigrant corpses such as bishops into sovereign indigenous soil had far-reaching consequences for U. S. history generally and the history of the trail specifically. And those far-reaching consequences stretched beyond the role of dead immigrants in dispossession to include the importance of indigenous defense of their homelands to shaping trail history. And this fact surprised me when I was doing research. This was not something that I expected to find as I worked on the book. Native voices and perspectives are scarce in the immigrant archive, and the thousands of trail letters, diaries, and memoirs that can be found in libraries across the United States that can be found here, and also perhaps in some of your own personal collections. But that doesn't mean native peoples weren't important to trail history. They absolutely were. And one of the ways they were important was in how they talked about their dead and their graves to assist in dispossession and to describe their suffering and sacrifice during forced renewables west. This drawing here by Cherokee artist Sam Watts Scott depicts one of the best known of these forced removal routes, the Cherokee Trail of Tears. But this Trail of Tears was also a trail of graves. The second image on this slide is of a letter that Cherokee woman Eliza Jane Ross wrote to her uncle John Ross in 1842, a few years after the Trail of Tears. In the letter, Eliza tells John, who serves as Cherokee principal chief, essentially the president about the dead along the trail. And she's writing here to blame members of the treaty party for agreeing to removal, saying that as a result they have, quote, seen the graves of their own people strewn many hundreds of miles along the roads and banks of the rivers and strange lands and amongst strangers without one friend to watch over their bones. This is the suffering of the Trail of Graves. And Eliza's words were just one of many examples of Native peoples describing their forced removal routes as marked by graves as well as tears. And they did so to document their suffering and the trauma of dispossession to try to better Native relations with the United States. And another key feature of the fight against dispossession that I trace in chapter one of the book is the ways in which indigenous peoples safeguarded and marked their ancestors' graves before they were forced from their home lands. And they did this for personal reasons and also as signs and symbols of their inextricability from the lands the U. S. was taking. But while this material and these arguments figure in the first chapter of my book, it's the last chapter I wrote, and it's the one that took me the longest to figure out because I started in such a dramatically different place than where I ended, which is not unlike a lot of immigrants who didn't know if they were going to go to California or go to Oregon when they started. So in the rest of the talk that follows, I'd like to take you chronologically, but I'm going to take you chronologically through my process rather than through my argument. There's really three periods that shaped my research. The first, where I saw the Overland Trail, is a viable research topic. Second, I got into the sources. I began to play step at the center. And then third, I entered the period in which I came to articulate the ways that Native peoples shaped the history of the Overland Trail. So I'll conclude with that final portion as well as a few comments about trail memory and memorialization. So at the beginning of my research process, my questions really centered on trying to understand sort of three things. How drives the Overland Trail continue to play such a prominent role in popular memory? And then the flip side of that being why had academics largely abandoned trail history? And then third, would it be possible to say something new about this major event? And not only something new, but something that contributed to the field of Western history that was striving to become more reflective of the diversity of our region. And the origins of these questions for me were really two central experiences. One which was specific to me and one which was more universal. So we talked about the second Oregon Trail game. We saw the paper towel low wagon, very nice. But now I want to tell you briefly about my Oregon Trail journey, which started as summer or two after I graduated from college when I got a paid internship at Fort Casper. That's me in the shadow wearing my nice blue polo. When I got to graduate school, all of my doctors wanted to know if I had to wear a costume. But no, it was a polo shirt. So I worked at Fort Casper all summer in Wyoming. I don't know how many of you have might have been to Fort Casper or been to that part of the trail in Wyoming. But it is, you have, fantastic. But it is breezy to say the least and very, very gusty at its most sort of strongest points of wind. So that was quite an experience for me not having lived in that environment. So I spent the summer there mostly outside, which is a great way to learn about the trail when they're spending five to six months outside in wagon. I led tours. I answered questions from visitors. I talked with them about Fort Casper being a paid ferry site across the Platte River. And all of this was really interesting for me because I realized through the visitors what a passion, knowledge, and interest that so many folks had for the trail experience. And at the same time I was talking to these folks and sitting outside and telling them about the district, I was also reading Western history books and preparing to go into graduate school. And I was realizing that people hadn't really written about the trail in a few decades. And so I was wondering why that was and what I might be able to do about it. So that's what was going through my head. What was most interesting to those Fort Casper museum visitors was my name, Sarah Keyes, which is the same name as the first person on the Donner party who died. Yes. So we all probably wished for some claim to fame. And this I discovered, at least in the trails world, was mine. A few signatures were given, photos were taken. But also, you know, even from the beginning of my exposure to trail history and memory, evidence is pointing to the prominence of death and dying in the trail experience. And then I got into the sources and there is a depth and richness to these materials that is really unparalleled. They're housed in archives at the end of the trail, you know, basically like where we are today or like the Oregon Historical Society, which is another of my favorite places to visit and do research. These sources are also in large archives with substantial Western history collections like the Newberry Library in Chicago. I mean, you can really find these things everywhere across the United States. And they can be found as standalone diaries. One example here is John C. Anderson's diary from Utah State Special Collections. They're also part of larger personal and familial collections. So this image is from the American Antiquarian Society. It's a letter about the Overland journey in the Shaw Web. Family papers was just a really large collection and one of their members went to the California Goldfields. And then this was one of my favorite finds is I also found Overland narratives in a pension claims file of federal government. So this last photograph is a snapshot of a microfilm card with paging information for the pension file of Edward J. Bartholomew's widow. And I don't know if you all are familiar with the J. Hawker Party that gets lost in the Mojave on the way to California. But Bartholomew was part of that party and his struggles and sacrifices during that sort of ill-fated journey into California also show up in his widow's sort of justification for earning of his pension, right? So it's about a civil war of sacrifices, but also it's Overland trail. So it's just fascinating that. And I bet some of you might know where some trail diaries are that aren't in libraries. You might have some on your shelves. And, you know, taken collectively, these accounts are, as noted, trail historian Dale El Morgan, a mosaic in words of the personal experiences of the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who pinned their hopes and set their sights on reaching the Pacific. Now, Morgan may be familiar with was originally from Utah. He spent years working at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. And I really like his phrasing here because I think it gives credit to the immigrants, some of whom struggled to put pen into paper for sharing their individual and familial experiences with the world. And as I read through their accounts, I kept stumbling upon attention to death. There was Silas Newcomb, an immigrant from Wisconsin who visited his mother's grave to say goodbye before heading Overland to seek his fortune in the California Goldfields. There was Abigail Scott Dunaway, who described her family's efforts to bury her mother in painstaking detail, including how, as with Charles Bishop, they selected a spot on a rise that was both beatific and prominent, a place that could be remembered. Or Vincent Hoover, who when he and his parents left his younger brother John's body behind on the trail, consoled themselves with the thought that by placing him so close to the Platte River, John would find companionship in the sounds of the water. And then there was Sarah Nichols, and this is the story that really gets me. There was Sarah Nichols, who as her husband and son took to the California Trail during a cholera epidemic, begged them to return to save their lives and her own. And they continued on, leaving her warnings unheeded until her son Samuel died of cholera on a steamboat headed up the Missouri River Valley to one of the jumping-off towns, those starting points on the eastern edge of the trail. Ultimately, Sarah's loss was mitigated that most losses on the trail weren't. Her husband, George, brought her son Samuel's body home. Now this was no easy feat in 1849, but George paid for a special double-lined coffin and he also paid freight on steamboats to take Samuel's body home to New York. And this return brought some consolation to Sarah. And so as I let my sources take the lead, as I turned an empathetic eye to their accounts, I began to see how central death and dying was to the immigrant experience. And it remained central to the memory of the trail today. This photograph is actually from 2015. It's a photograph of the grave of Abigail Scott Donnelly's mother. She was reburied by members of the Oregon California Trails Association in 2015 and her remains were remarked. And so in many ways they were doing the same thing that her family had originally done for her when she died in 1852. So seeing death at the center of the trail, and then as I zoomed out from the trail to the larger context of death and culture, in 19th century America I found that it made perfect sense that it would be. In the mid-19th century pre-antibiotic United States, death was everywhere. It was omnipresent in a way that it isn't in 20th century America. And this is not to discount the tragedies of the COVID-19 pandemic or other losses, but it's simply to impress upon us how different life was in the 19th century. And then one way to grasp this omnipresence of death is to grasp variations on one of the most common phrases of 19th century America. If I live. This phrase was something that 19th century Americans might say to a conversation partner when talking about future plans. And it was certainly a phrase that appeared in many 19th century letters. The most important medium of communication at that time. Here's one example of a use of this phrase. When John Minto, who's circled in red here, and he immigrated overland to Oregon in 1844 in one of the first wagon trains to make it there. And then in 1901 he dictates his reminiscences of his journey to an Oregon historian, H. S. Lyman. And when Minto tells Lyman his story about how he decided to go to Oregon, what he says is he said, well, you know, my family and I were having Christmas dinner. We finished up and I just told them, if I live, I will go across the Rocky Mountains. I think that probably went over horribly with his mother, but that's what he said. John was really lucky though. He lived until 1915. He died at the age of 92. I know, but that was really unheard of for someone of Minto's time. And in fact, people born in the 1820s and 1830s, that's the decades of birth of many overlanders, had some of the lowest life expectancies of the entire 19th century. So Americans at this time were powerless to prevent death, but they could and they did choreograph their responses to it. They gathered to listen to their loved ones dying in moral instructions, and they dutifully narrated the scene for distant friends and relatives. With the soul gone, the body became the focus of the moralization. Where Americans laid their loved ones out, they wrapped them in shrouds, buried them close to home, and they waited for the day they would be reunited in heaven. As they had cared for their dead, anticipative survivors cared for their connection with their deceased loved ones. They fingered lots of hair, they gazed on miniature portraits, and most importantly, they visited their graves. Graves were seen as portals between the dead and the living, and tranquil beatific places for the living to commune with the dead. This embroidered morning picture from about 1810 captures this role of the grave. You have two mourners, a girl and a boy, paying their respects. This is something that could have hung in someone's home. The willow that's bending overhead symbolizes the grief. The two urns on top of the tomb symbolizes two lost family members who were buried within. Normally people would be buried individually, but in this case these were two very young children who died, or relatives, so they were buried together. I don't know if anyone's seen this type of embroidery work in person, but women could do it, girls were trained to do it, and it's just absolutely gorgeous, it takes a lot of time. It's really representative of the type of artwork that was being produced in this time period, and also the centrality of death to these types of productions, the attempt to keep that grave close. It's the grave to which mourners form specific attachments. This is the reason why Sarah Nichols was in such despair that her husband and son might die on the journey. It's also why Margaret White Chambers, who traveled to Oregon seven years after John Minto did, described the fear of leaving loved ones on the trail as perfectly agonizing. Now in the earlier image from Ruff, we saw a good depiction of how people cared for bodies on the trail, and this image we see the fear and concern of what would happen to what was left behind. So you see this absolute onslaught of wilderness forces. After the grave that was left behind, you have the coyotes digging in, you have the bear with exceptionally long path of claws waiting for his turn. It's not only the physical memory of John Smith that's being erased, it's also the individual identity that the headstone is ragged, and there's scratches on the details of his death and his age. All of this is symbolizing utter destruction, and this is sort of at the center of immigrants' experiences of fear, of death on the trail. And this type of concern, of course, was one that we already saw noted by Eliza Jane Ross in 1842. So that's nearly a decade before Ruff drew the fate of many. So here I'm moving to the third and final section of my process where I talk about the connection between overland trail history and native history. Now, while Eliza's words about the trail of tears as a trail of graves are telling an evocative, they weren't the first piece of evidence that made me begin to investigate the connections between forced removals and the voluntary migration of immigrants across the overland trail. Those words came from someone else, and I bet if I didn't have his name on the slide, you could still tell me who he was. Those words came from someone else, someone who used his power to become one of the direct causal forces of indigenous removal, President Andrew Jackson. So I was at this point in my research where I was working to place immigrant descriptions of the emotional toll of leaving home and their dead behind in a larger context. And while I was trying to do that, I picked up a book by another historian named Susan Matt. And Susan Matt has written a book about homesickness in US history. It's really interesting. It's wide-ranging. It talks about a lot of different peoples in the United States and how they dealt with homesickness. And Matt's really challenging the idea that Americans were inherently mobile and uprooted. So she's really looking at that toll of leaving home behind. And in her book, she included an excerpt from a speech that Andrew Jackson had made to Congress in 1830. Now, Jackson was elected president in 1828. It's actually the same year that Eliza's uncle John Ross became principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. And as you probably know, Jackson's a man whose moment of fame in war helped him launch his political career. He's also riddled with old bullet wounds and at least one bullet. He's plagued by chronic digestive issues. And he becomes the face as well of an increasingly hard-line belief in racial difference between whites and natives. And he becomes the primary proponent of full removal. And then in his second annual message to Congress in December 1830, he says this. And so he's laying out his vision of removal as one that was necessary and little different than white voluntary Western migration. And so he says to the representatives, doubtless it will be painful to leave the graves of their fathers, referring to native peoples. But what do they do more than our ancestors did or than our children are now doing? To better their condition in an unknown land, our forefathers left all that was dear in earthly objects. When I first read this, I thought, why would Jackson be talking about the indigenous pain of removal from the graves of their fathers? And how did he need to come to refer to this in his speech? Jackson certainly had no sympathy for native pain, but some, in fact, many representatives did. Jackson's removal actually passed earlier in 1830 at the end of May, but it barely passed. And so in this report, Jackson is telling Congress how removal is going. And he's also trying to mitigate native pain by comparing it to voluntary Western movement. And I'm wondering, why does he have to talk about this? And so I looked out into other sources and started investigating what was happening in the discourse around forced removal in the time period. The time period that sort of immediately precedes the surge of migration across the Oberlin Trail. And I realized that descriptions of native homelands as holding the bones of their fathers, descriptions of native claim to their land, as through these connections to their dead, were absolutely everywhere. They were in the printed press. They were in letters that John Ross himself wrote to congressional representatives, begging them, is it true you will drive us from the tombs of our fathers and of our mothers? It's even referenced in William Lloyd Garrison's liberator, the most sort of the publication is at the forefront of the abolitionist movement. And Garrison says, hey, you know, African Americans are as opposed to this idea that you might free them and send them to Africa as a charity are opposed to being removed from the graves of their fathers. So I realized that it's showing up again and again and again. This example is from even earlier, it's from the 1820s during a conflict over Illinois territory, where the SOC chief is defending or explains people's connections to the land through their graves. And then finally it shows up here as after removal. Because one of the things that historians now know is that while many native peoples were forced to remove, some were able to evade that removal. Some got special exemptions from the government, others simply hid like this creep man. Who's when he's discovered by tourists, begs them not to reveal his hiding place. So he will not be removed from the bones of his ancestors. Now while some native peoples were able to remain in their homelands, many weren't. Many were forced westward in detachments that were funded by government money. But even as they're being forced to leave, they remind white audiences that their graves and their bones connect them to their homelands. And they also take particular steps to mark those graves. So this is a quote from a creep chief, even as he's being pointed westward away from his homeland, says again that the land he's being forced from is the land of his father's bones. You have another native leader here saying that when whites are taking their land, they're not just taking their land, they're stealing the graves, they're stealing their debt. And to say this to someone in the 19th century to basically call someone a grave robber is kind of the worst thing you can call someone at this time period because of that reverence for preservation remains. Other things that native peoples do before they're forced to remove is they mark and memorialize their debt to make sure that they'll be remembered just as immigrants did on the trail. So in this is an example of a monument the native peoples erected over the graves of their dead. And then others not only marked the graves before they left, but they also took mementos with them. The Miami, for example, took plots of dirt like these and small stones from the graves of their dead before they were forced from Ohio to Kansas. Then they're forced on these routes. And so beginning in the 1810s, along these forced removal routes, we have westward trails of indigenous graves that originate in the north and south and converge on the eastern edges of the Ozone trail. And many of the deaths on these forced removal routes were also caused by cholera. Justice cholera would cause some of deaths on the voluntary immigration westward. And it's actually daunting to try to treat people or help people who have cholera when you're on a moving wagon train. So even when the leaders who are leading these native wagon trains westward stop and get additional caretakers, people are too scared to come and help them. And cholera is caused by a bacteria, but no one at this time. White people or native people know that they should wash their hands or that they should stay away. They should distance themselves from water to keep it from being polluted with this bacteria. And so if you're in a highly compacted wagon train and you're also trying to move, deaths can happen very, very quickly. On one detachment of Cherokee people who contracted cholera on their forced removal trail in 1834, in the space of two days, Black Fox lost his wife and three children, Will Tucker lost four sons. And then not only do people die, but when they're sick, they have an absolutely horrible time because they're trying to keep these trains moving. And so sick people might simply be put inside a covered wagon. It gets really hot in there. It's really uncomfortable. They don't know about things like shocks, right? And so it just makes it horrible. It's a very, very challenging experience. But one of the things that we can see in the documentary record is that even in the face of these challenges, native peoples are able to carve out some help and sort of extra assistance for themselves. And they do so through protest and through making demands. So there's one example, for instance, when a daughter of a Cherokee leader dies during a wagon train migration that the people demand that they be given extra time, multiple days, to prepare her body for burial and to bury her as well as possible. So just like the men in Bruff's Company who united to care for Charles Bishop, you see the same thing happening on these forced removal routes. So, at first glance, the removal period and the overland trail might seem to have little in common beyond their iconic stature in U. S. history, but historians have begun to see them as inextricably linked events with the journeys of forced dispossession enabling the ones of possession. As in Distinguished Historian Elliot West put it some 20 years ago, removal and the trail were twin migrations. Training the spotlight on death provides another way to connect these two historic touchstones. What became the central plot of the overland trail in its role in national expansion, risking death on the way, dying in unsettled country, and being buried far from home and family had already been established as the central plot of the removal era. But these similar plots were turned to distinct ends. Indigenous peoples lived, narrated, and moralized their experiences of death in opposition to, rather than in concert with, U. S. settler colonialism. In articulating their attachment to their homelands in terms of their sacred and emotional ties, the graves of their fathers, Indigenous people broadcast a particular form of placemaking that also became the metric against which their opponents measured white attachment to home. By the time white Americans began to create landmarks of death on the overland trail, they did so in a context defined by Indigenous activism against removal. Voluntary westward expansion and the contingencies of dying on the overland trail did not emerge out of a cultural vacuum, but rather a decade-long, cross-cultural conversation about death, graves, and territorial claims. And so I want to end this evening with a call to continue efforts to reconfigure trail history sites to include Indigenous perspectives. As of now, most continue to foreground and center the immigrant experience. One prominent example is the Donner Monument, also called the Pioneer Monument Not Far From Us, which sits near where that ill-fated Donner Party. The Syracuse was on, although she died in Kansas near Alcove String, so she did not participate in cannibalism. I am free and playing from that. But the Pioneer Monument is still there, and it was sponsored to celebrate that triumph of immigration. It was sponsored to recognize the immigrants who came after the Donners and persevered through the mountains, and it's still standing today. It was erected in 1918. And it remembers that history, but I think it's also a sign of how much work we still have to do around the Oberon Trail. How important it is to continue to write histories of the Oberon Trail, to remember it, and to remember it in the many ways that it was important. The many ways in which it was a story not only of immigrants, but also a larger story of U. S. westward expansion, and a story that also included the dispossession of Native peoples. Thank you for your time this evening. Thank you. How long did it take you to write your book? Oh, it took so long. It felt like the longest Oberon Trail journey ever. So I wrote it as a dissertation, and I was really unhappy with the dissertation, and I just kept writing and thinking and researching, and so it took me about ten years. Yeah, that's a really good question. Did you raise your hand? I'm looking for three wedding trees. Okay. And often they'll say, so-and-so led the train, and there were so many people on it. And then they'll list names, and they'll only list like twenty names. Right, right. So where does one go to find names of people? I can give you my email, and if you tell me specifically the trains you're looking at, I can connect you with some folks who should be able to help you out. Yes, yes. How long did the trip take, and where in the trip did people start dying? Really good questions. You could die anywhere. It was a little bit random. Actually, on the eastern edges of the trail where it's so dense, particularly when they're waiting around these water sources during the crowded bullet rush years, it takes like a week for days to cross it at a ferry crossing. There's a sort of a high bump in cholera there, and it declines after you get across South Pass, so that you can still get something else or get sick. And then the journey itself takes six months. Yeah, so that's a long time. A long time of being outside. Why does it really count as being inside? Yeah, yes. I had a question. When you were at Fort Casper, it got the name from a soldier who was in a tremendous battle. I think he was at a bridge in defending a bridge or something. Absolutely, that's exactly right. What happened? Do you remember? Yeah, so, oh shoot, it's been a long time since I went on those tours, but I think he's killed, right? No, it was an incredible pitch battle. Yes, unbelievable odds. Yes, he is. I thought you might have told the story at this point. Yeah, we focused a lot on the immigrant history, actually, unless on that Civil War era period, because those buildings themselves that I worked at, those had originally been built during the Civil War period after most of the immigrants had come through, and then they rebuilt them with WPA money in the 20th century. And the story was that they'd staged a fake attack on the fort with flaming arrows as some sort of celebration they were having. That never happened, like a recreation, and they burned down the original forts. Yeah, we had another chance. Bishop, is that the town named after him in California? Bishop, you were talking about this. Oh, I don't think so. Yeah, but that's a good question. What percentage of the people that started out on the trail survived? Oh, that's such a good question. Yeah, that's such a good question. So there's this great, thick book on the trail by John Unruh, Plains Across, I don't know if you all know it, but he's done the most initial research into numbers of death and rates of death, and he actually thinks it's not super high, and it wasn't that much higher than if you'd stayed at home in the United States. But they talk about it a lot, and then if you can't really mark a grade well, well, it could be anywhere. So it kind of becomes this thing that you could find a grave anywhere in the landscape, and then that itself makes the entire west sort of the sacred place of American suffering and sacrifice. And then there's also a geographer who's done a lot of work on sort of parsing real trail graves versus sort of like narratives of trail graves, and he more or less agrees with these earlier numbers from Plains Across that are lower than you might think, yeah. To what extent has the indigenous tribal members the descendants of the forced migration of the Southeast tribe have gone back and remarked their descendants? Yeah, that's a really excellent question. Some of that work has been done. One of the periods of sort of memorialization of those indigenous dead around the forced removal roots actually begins with members of white historical societies marking those graves themselves. And they do that with some sympathy for the Native peoples who are forced on those roots, but also there's a strain of doing it as a way to say Native peoples are of the past and gone, and we're stepping in to do this for them now that they're no longer here. Whereas, of course, Native people talk about present, future, survival, persistence. So that's an interesting tension there. Yeah, that's a great question. Was there a gathering place in the east where you started on the trail? Where was the starting point? That's a really good point. A number of gathering places, a lot of what they call these big jumping off points, particularly in Missouri and Iowa. St. Louis is sort of a hub where a lot of people might arrive by ship. You go to a place like St. Joseph or Council Bluffs in Iowa. And particularly during the cholera years, there's a lot of competition between these towns because they want the immigrants to come to their towns so they'll spend money and camp there and get all their provisions there. And so these towns will say, well, don't go to Council Bluffs, there's cholera there. Come to St. Joseph. Yeah, so it's all along that kind of area. Yes, go ahead. When the Transcontinental Railroad was completed, did the wagon trains just cease or did they still have them going up to the northwest and southwest? Yeah, that's a really excellent question. So immigration by wagon training declined substantially, particularly after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, but some people are still using wagons because they're going, like you said, to these locations that the railroad doesn't go. And also because the railroad is not cheap, right? And so there's even some of the well-heeled tourists who are some of the first people to take the Transcontinental Railroad after it's finished in 1869. They'll write about seeing wagon trains from their windows. The train, though, and I think railroad companies in the 19th century are like some of the most powerful historians of the 19th century because they have huge publicity departments about how great they are for the United States and what they've done for the West. So the railroad company's narrative is train came in, the modernity of Iraq, we did it. No more wagons, no more danger, no more death. Oh, look at that immigrant gray about your window. Aren't you glad you're not doing that and that you're sitting in our Pullman cars? So that's really interesting, too, and how they play with that. So you're in New York, 1849. Yeah. You want to come to look for some gold in California. Yeah. Which way, which route would you take? Depends on what you want. You want to get there quickly? Or do you want to have the adventure of your life and go overland like every good American? I know. What are your features? Me? Yes. I go overland. Yeah, yeah. I'm going to list all the illnesses again. And how communicable they were. Did anybody ever survive them? And did the people stay on the East Coast still like the people that were caught on the trail? So, oh, those are all so good questions. There's a lot of weird 19th century words for a lot of diseases and they don't always label them correctly. But they do talk a lot about cholera. It's like sort of the primary fear dysentery, which we got from the game. Mountain fever, other fevers. A lot of people die from accidents too. They don't have good firearm safety. They don't really know how to swim, so if you're crossing a bunch of rivers, that's not so good. But your question about, is it connected to what people died of at home in the 19th century? Absolutely. And that's one of the things that I found, what I really wanted to do in the book, was connect the trail to that 19th century context. That yes, it's different and unique, but these people are bringing, they're having similar experiences that they would have had at home, but in a different place. And cholera is typically associated with deaths in urban centers, and it's particularly been blamed on sort of immigrant populations in poorer areas of cities like New York. But it's everywhere. It can get anybody. It's getting all the white Anglo-Saxons on the trail too. Yeah, yeah. Yes. And then there's childbirth, right? Oh yes, that's true. So actually Abigail Scott, Dunaway's mother, who dies in 1852, the one they spent a lot of time burying, and then she's reburied in 2015. So in the documents from 18, in the original diary that Abigail herself kept, she was like a teenager, and her father said, you're the one who has to keep the diary. She ends up, I don't know if you all probably know, she ends up becoming a writer. She makes money off of her writing when her husband doesn't, can't keep the job. But she, they say her mother died of cholera in 1852. But as part of, part of the reburial happened because Abigail's mother's aunt's roommate had initially been dug up and they were actually examined by scientists at the University of Wyoming. And they, they showed that she had major physical harm from a child she'd given birth to shortly before she started on her journey. And so in fact, her pain and then her sickness was probably, actually, stretches back to starting from that horrible child birth experience and then not being able to recover before they started on the wagon train journey. News in happening on the trail too, yes. Yes. Because she, an Hispanic, went up in the Southern sport as a spy. She was known for stealing horses. Oh really? And, and a flipper. She might share a name. Has anyone seen this site? It's out in Eastern Nevada. We, I actually, I got a moment, oh, she's a wonderful photographer. She's also trained as a geologist who lives out in the Elko. She went out and got this photo for me for the book cover and we managed to get this in winter. We didn't want any snow. It was snowing, snowing, snowing. We only had like three weeks to get the picture and then finally the, boom, the sun came out and she ran out there with her camera and captured this, this beautiful landscape scene. But this was sent to Duncan. There was a story told about her for a really long time. Rero told the story too. She was this young, virginal maiden who succumbed to cholera on the journey. That woman was a grandmother. So, yeah, that was the kind of stories people told about these graves. Yes. Did you come across James Beckworth? Oh yeah. And emancipated an American with two sparks. Yes, absolutely. I think that's a really wonderful example of recognizing the multiplicity of people who played a role in this history. Yeah. Yeah, he's a really good example of that. Mary the crow. Yeah, yeah, absolutely. Yes. Yes. Just a quick one. I know some family, I guess you could say a little man to us, but the stories of the crows playing on the organ crows, I think they split it up half way. Yes. Unfortunately on the California Trail. Oh really? And they didn't make it. And they found it a town in the center point. It is an organ with a Elizabeth mat above on my grandmother's. Oh wow. And so, where do I, this is just one of my family stuff. Right, right. So, where do I put this stuff? That's a wonderful question. I mean, maybe the folks here are interested in it, I don't know. The Oregon Historical Society might be. Yeah. The Oregon California Trails Association also has a big collection based in St. Joseph. So, those would be good places, I think, to follow up with and see if they're interested in it. Yeah, but that's a really important family story. Yeah. Okay, yes. Yes. First, thank you so much for just expanding on this link between dispossession and settler colonialism, especially now. And my question is, do you have other examples of indigenous activism towards reclaiming, say their burial practices, or their sites, as they're on these trails? Yeah, that's a really good question. So, I think one vignette really gets at your question, the story that comes from the early 1860s. And Fort Laramie, which I mentioned, sort of in that corner of Wyoming, that's one of the most iconic landmarks and stopping points on the Overland Trail. That's where you're going to fuel up, try to get some mail, all these other things. But the fort actually has an indigenous white history that it was actually built to trade with Lakota people. And because of the close relationship between particular bands of Lakota and the white traders in the U. S. government at the fort because the Lakota and the U. S. are allies for quite some time until we get later into the 19th century. There's also a Lakota place where they're dead right up near the fort. And by the early 1860s, the Lakota and the United States are at war because the U. S. keeps taking land even though there's treaty agreements to protect it. And so a Lakota leader named Spotted Tail, very sadly loses his teenage daughter, she dies. And it's in the middle of this conflict with the United States and he decides that he's going to bring her back to the fort where she grew up and had so many happy memories and some of her ancestors are buried. And he's going to do so as a sort of political diplomatic offering to remind the U. S. military at the fort that this is a shared Lakota white space and to try to go back to relationships the way they were before. And so this is a symbolic choice that he does to do that and to try to make those negotiations. You can see in the written record the white military officers think one thing is going on and that he's like surrendering and asking for peace and he's clearly saying, no, I'm reminding you of what this place has meant for us and what we had agreed to. And when relationships get so bad because the United States refuses to adhere to the earlier agreements, he eventually goes and removes his daughter's body from that site and takes her to a new reservation. But that's an example of that attempt to protect and then also give that meaning to those deaths. Yeah. Well, you all have been an amazing audience. Thank you so much.