Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2025-01-16 - San Juan Ridge Tapestry Project with Bruce Boyd and Jennifer Rains Crosby (48 minutes)

For our January 16th presentation starting at 7:00 PM, we will hear from Bruce Boyd and Jennifer Rains Crosby who will be sharing on the origin and historical detail of the San Juan Ridge Tapestry Project. A PowerPoint presentation will provide images and details of all twelve tapestries.

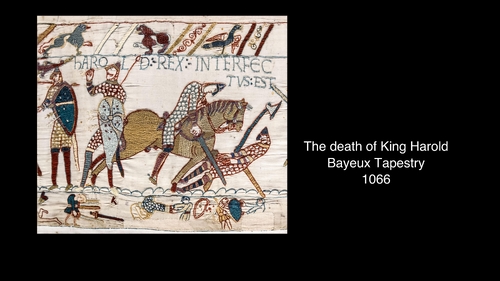

The San Juan Ridge Tapestries are a group of twelve individual tapestries depicting the rich history of the San Juan Ridge from prehistoric times to recent cultural institutions created by and for the San Juan Ridge Community. The project was conceived and executed by a group of dedicated women and men of the San Juan Ridge beginning in 2007. Materials and techniques were modeled on the Bayeux Tapestry, a 1,000 year old Medieval tapestry in France celebrating the war of 1066. Each tapestry is embroidered by hand on linen from full size background drawings. Each tapestry illustrates a specific chapter in the history of the ridge community.

The San Juan Ridge Tapestries represent the living history of the San Juan Ridge. There are thousands of hours of hand stitchery using fine woolen yarns by men and women of the community in weekly stitching sessions from 2007 to 2022. Originally created to be housed in the North Columbia School, to wrap around all walls of the main classroom space. The Tapestry is now stored in a climate controlled and fire safe archive. It is available to be displayed in the schoolhouse or other venues from time to time. The last showing was at the June 2024 meeting of the Nevada County Historical Landmarks Commission at the North Columbia Schoolhouse.

The San Juan Ridge Tapestries are a group of twelve individual tapestries depicting the rich history of the San Juan Ridge from prehistoric times to recent cultural institutions created by and for the San Juan Ridge Community. The project was conceived and executed by a group of dedicated women and men of the San Juan Ridge beginning in 2007. Materials and techniques were modeled on the Bayeux Tapestry, a 1,000 year old Medieval tapestry in France celebrating the war of 1066. Each tapestry is embroidered by hand on linen from full size background drawings. Each tapestry illustrates a specific chapter in the history of the ridge community.

The San Juan Ridge Tapestries represent the living history of the San Juan Ridge. There are thousands of hours of hand stitchery using fine woolen yarns by men and women of the community in weekly stitching sessions from 2007 to 2022. Originally created to be housed in the North Columbia School, to wrap around all walls of the main classroom space. The Tapestry is now stored in a climate controlled and fire safe archive. It is available to be displayed in the schoolhouse or other venues from time to time. The last showing was at the June 2024 meeting of the Nevada County Historical Landmarks Commission at the North Columbia Schoolhouse.

Author: Bruce Boyd and Jennifer Rains Crosby

Published: January 16, 2025

Original Held At:

Published: January 16, 2025

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

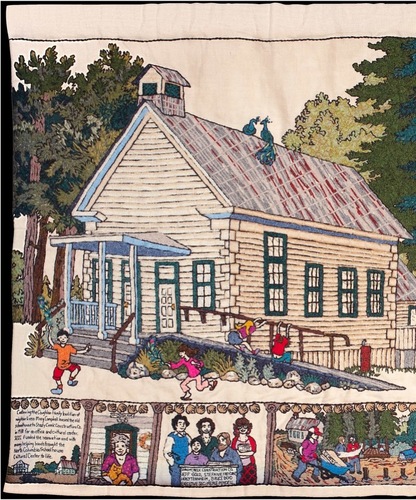

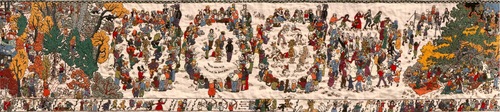

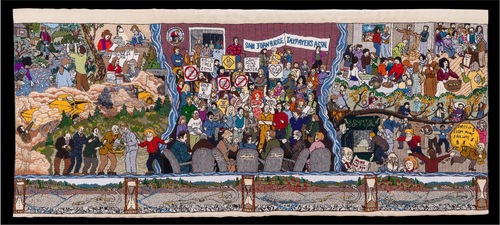

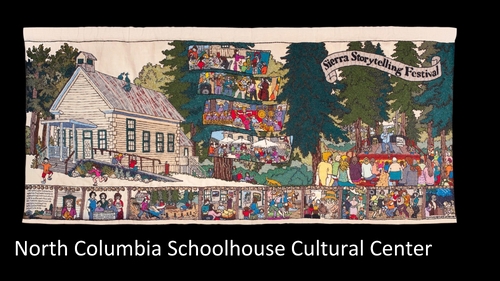

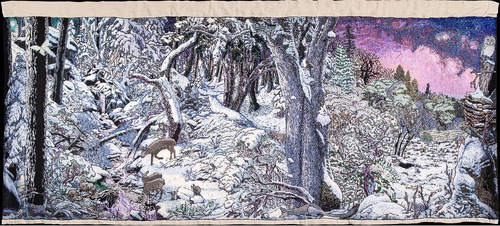

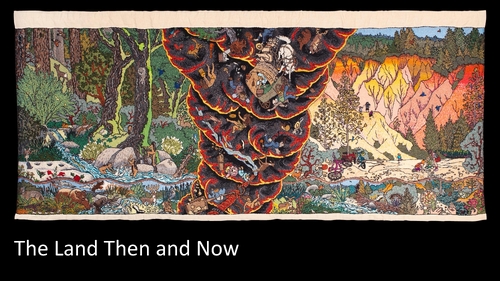

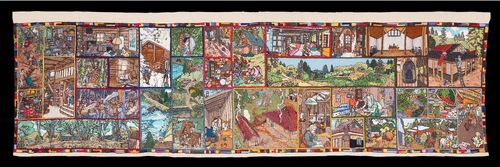

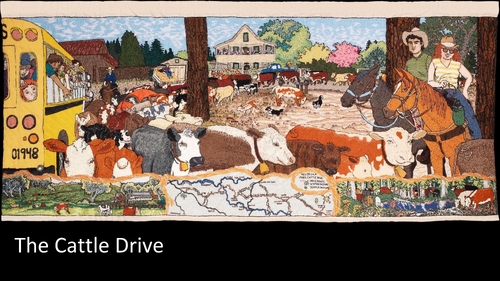

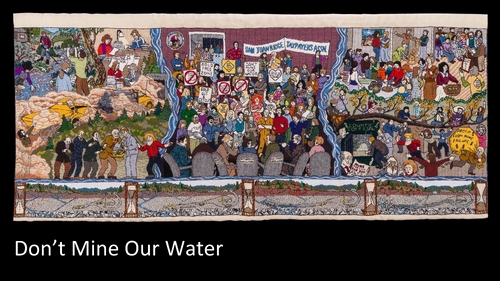

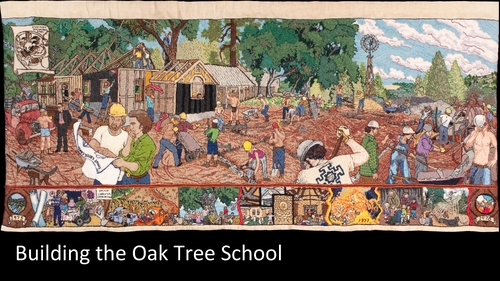

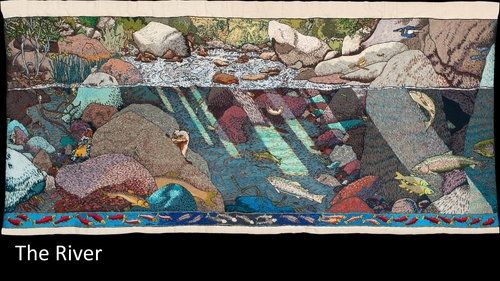

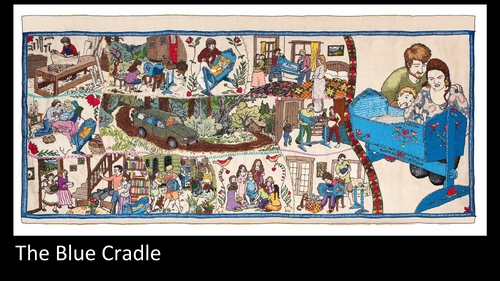

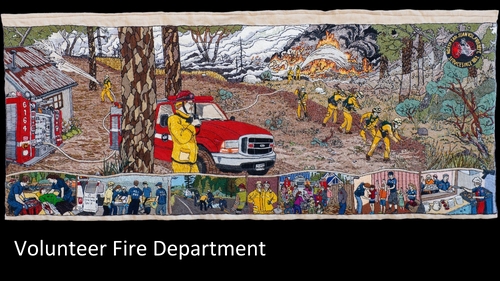

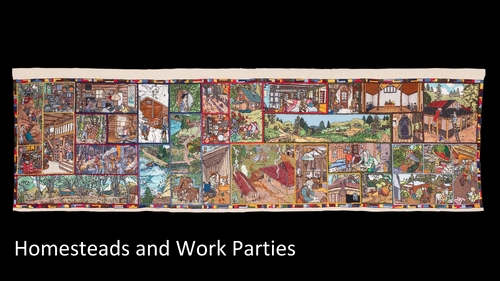

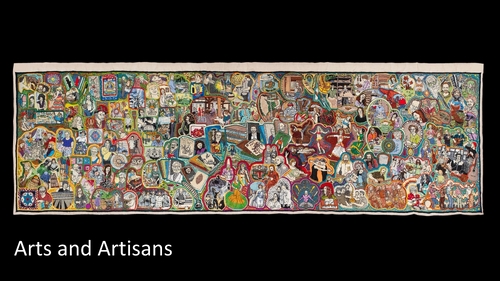

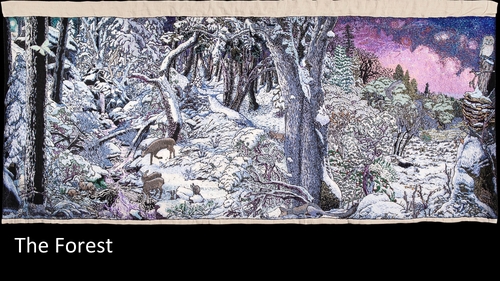

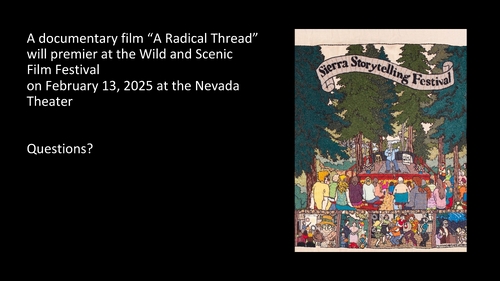

So anyway, thank you for coming to this show. We just, on Tuesday, Jen and I did a presentation to the Board of Supervisors, and the tapestry project was designated as the cultural resource of the county. The first designation of the year, we put on a very short program with them. We got 10 minutes, which was really generous of them in their busy schedule. So, and then my friend Bernie Zimmerman from the Landmark Commission, I'm a member of the Landmark Commission, suggested to Daniel that we ought to do a presentation here. And of course, you always volunteer when Bernie asks you to do something. And Jen, I'm not part of the tapestry project, but my office is in the North Columbia Schoolhouse, and I've been there for 50 years, and I am sort of involved in everything that happens up there and somewhere and another. And so I've been through the Landmark Commission, and then the tapestry committee that kind of is shepherding this project through. I've taken on this role of trying to speak to all of you. The tapestries consist of 12 tapestries. They covered the history of the San Juan Ridge. They were originated by Marcia Stone, who is a textile artist from the ridge, a longtime artist and resident. And she had the idea that somehow she wanted to convey the recent back-to-the-land history of San Juan Ridge, because there's a lot of different stories about the San Juan Ridge. And so she wanted to get that in a form that could be shared with the community and the rest of the county. And in researching that, she discovered the Bayou tapestries, which chronicle the Battle of Hastings back in 1066. It still exists. It's 950 years old. It's on display in Bayou, France. It's an incredible tapestry. It's 224 feet long. It was designed to go around the walls, the high walls of a cathedral in Bayou. And they would display it maybe once a year, twice a year, and then it would go into storage. And the techniques and the colors of how the Bayou tapestry was done, Marcia decided that that was something that would be a great medium for telling this story. And so they started in 2007. There's been over 10,000 hours put into doing embroidery on these 12 tapestries. Now tapestries are generally woven, and then there's this kind of generic, kind of like the word aspirin, that covers wall hangings. But this is an embroidered, all these tapestries are embroidered, which means skidges and knots, very finely done with needles. All their name would be needlework, and sometimes the Bayou tapestry is now called the Bayou embroidery. So it's following in that tradition. In the beginning it was limited to the eight colors that were used in the Bayou tapestry. And then as all these people came to work on it over the years, the creative juices of the ridge, it expanded. And some of the detail, they needed more colors. Jen's going to go through all of this. But when you see like the last, excuse me, I'm losing my voice, I always do, and you'll see the progression from something that was similar to the Bayou to something that is kind of fantastic art. So I wanted to start with a little bit of history, and this is more like history from eighth grade. So this is a little bit of history of the battle of Hastings in 1066. And that was a war between the King of England. He was an Anglo-Saxon named Harold God's Windson, who usurped the throne after King Edward died without a successor. And William the Duke of Normandy said that he had been told that he would be the King of England. But Harold took the throne, so William decided to invade England. And the Normans of France were descended from Vikings, and they assimilated into this kind of French culture in Normandy. So he invaded, and there were skirmishes in 1066. It culminated in the Battle of Hastings, where the English were defeated. There was maybe a thousand, they don't really know how many knights and soldiers and cavalry they had, but it was probably about a thousand army people on each side. And during that, Harold was killed. This is a little snippet from the 224 feet. And there's a lot of controversy over how he was killed. And current thinking is that it wasn't an arrow to the eye, which is what this depicts, but really gruesome, typical medieval hacking somebody to death. Anyway, this is just an example, and the thing you'll notice here is that the linen background, this is a woven linen, is exposed. It's the background, and the only things that are embroidered are the figures, lines, and some fill in some of the animals and the figures. And then at the bottom, there's these little things that kind of detail different parts of the battle. That ended after it took another three years for William the Conqueror, he became William the Conqueror, to subjugate the rest of England. And that was the last invasion in England. It hasn't been invaded successfully since. There's been some excursions, but nothing much. So, I think that's really about all I need to say on that. Oh, I should mention that it's a linen background, and Xanwong Tapestry uses the same linen background, and wool yards, that's how it was started. And those colors that they had back then were russet, blue-green, gold, olive-green, dark-blue, black, sage-green, and blue, just eight colors. And you'll see that when Xanwong gets into the tapestries. So, I'd like to turn it over to Xanwong. Xanwong is the artist that did the backgrounds for the tapestries, and she's been involved in the project from the very beginning. Hi, everybody. Nice to see you. Jennifer Rayne Crosby, and I grew up on Xanwong Ridge. I moved out there in 1875, and I was five years old. Marcia invited me onto this project in 2006, and I didn't know if I could do it, because it was so huge. I'd illustrated books before, and flyers, and small projects, and each one of these drawings was 30 inches tall and at least six feet wide. And so it was very intimidating, but it was also very, very exciting. I liked her idea of sharing the history of the ridge from her vision of the people that moved there, and also people that were living there, mixing together, and then the things that we value that would carry that forward and remember what's important to us. So, when she saw the Bayou Tapestry, this is how I remember it, is that she saw this book, and it hit her that this was something that people made, and that we could do something similar, that anybody could just start stitching this. And so she asked what kind of lids were used in the Bayou Tapestry, and so threads were used in the Bayou Tapestry, and she brought them together, too. Come on, work for me. This is going to go all the way into the future, isn't it? Oh my God, number seven at least now. Okay. I can just sit next slide. So, in this first one, we had this huge enormous list of all the different stories that we wanted to tell. There was, like, so many, and we couldn't decide which one to start with, and so I volunteered that what we should do is start with this local ceremony that happens out in the woods that I'd been going to since I was a little girl. Like, I could just dive into this while we were figuring out what the chronology of all of the stories was going to be, and I could use my memories, and I knew who I should talk to to find photographs and to corroborate our stories, and so it goes from left to right, and it begins over in the left-hand side with everyone parking in a meadow and then walking up this steep hill up onto this ridge top, and then the circles in the middle are depicting different ceremonies that happen on that day, and on the far right is the end of the day when we're having picnic underneath the tree, and there's a volleyball game, and there's music around the bonfire, and along the bottom, you'll see, let's see, does this work here? Along the bottom, you'll see that just like the Bay of Tapestry, there's another storyline happening, and so there are the things that are happening before. Each of the ceremonies, this right here is the Government Parade, there's the Arrows Ceremony, that's the offering of cornmeal, people speaking from the heart, and then saying goodbye and everybody going home. But there's all of these different stories following the Bay of Tapestry. There's also this border on the top, and so we have three main sections. We have this main area here, which is like the central theme for our story, and then we have this long one on the bottom, which is like telling more details about the story, and then this one here only appears on this one. It moves down into this area on all the rest of it, the dividing area between the thick and the thin. This tapestry is 12 feet long, just to give you a perspective. And it's right underneath his office. And it's two pieces, right? I think it was actually three pieces because it was so long that I didn't have a space where I could draw something that long. But it was problematic trying to figure out how to bring those pieces together and have it be continuous and not have any kind of break in the lines, and so we quickly moved to one of these six foot long tapestries, where we could do it all in one piece. So we knew that the second one had to be the North Columbia Schoolhouse Cultural Center because this was the inspiration for where we wanted the tapestries to live and it was one of the first places where our community really started to feel itself. They worked with the Coughlin family who owns the building and the land and asked if they could have a cultural center there and then they worked together to make that happen. And you can see that right here. People are making the amphitheater, which is also over here. And then you start seeing these little scenes along the bottom that are all the different kinds of events. And there's so many events that they had to go up here in these little vans as well. And then like the biggest event that still happens there today is this year's Tourism Festival and we have Steve Sanfield upon the stage because he started it all. It was his grand idea. And along here is this border of many hands because the making of the cultural center, the amphitheater, the ongoing volunteerism is the work of many hands. There's been lots of programs in the schoolhouse. Yeah. Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Steve Sanfield, lots of music and it's still very vibrant. So you can see that the colors have changed. That we were being very close to the bayou tapestry as close as we possibly could. The threads were a lot thicker. And then here it started moving into brighter colors and a big voice and anchor for moving forward. Anchor for moving forward, that's kind of interesting. The driving force for moving forward was our lead stitcher, Mary Moore. And right up here is the Balinese dancers who come out there every year and just could not do their costumes with the bayou colors. You need to have bright paint and bright purple. And so it started to move right there. Of course Mary loves color and so it was going to move pretty fast into the third tapestry. This is a six foot one. This is another six foot one. So the six foot tapestries fit exactly between the windows. So if we go back here, you can kind of see the building. So inside of the building in between those windows is six foot tapestries. And in this one, Marcia wanted to tell the story of the gold rush in a way that had never been seen before. And she had seen these paintings by my new artist Frank Day and was really, really moved by his depictions of whirlwinds. And she thought whirlwind would be a pretty good metaphor for the gold rush. That everything got stirred up and moved somewhere else. And so on this side, this is how she imagined the land before. This is the gold rush. And on this side is what we know the land looks like now. And under here, this is all the animals and plants before. And these are all the animals and plants that are here now. And there's this lovely little spot down here where you have this magnifying glass and these sundews because the sundews are out there in the days if you go looking for them. And this ropey pattern is like time. You imagine that time is a rope. So this is one of my favorite ones. I just feel like I loved her idea of the fiery whirlwind and I had a really great time drawing everything just tumbling through the air. So this is a really fun one to look at if you're able to see it in person. So this is the fourth one that I illustrated. And it's the cattle drive and it shows the building across. So over here, kind of off-screen is where the cultural center stands and this is the Coughlin's ranch house. And Marcia really wanted to work on Don't Find Our Water which ended up being number five but I felt like we weren't ready for that so we worked on this one. And again, I used my memories of being on Tylerfoot Road and being marooned by cows. And I was one of these kids on the school bus where we were all trying to touch the cows and I was also in this little VW bug with a barking dog and I just thought it was wonderful. This is the only tapestry that has a map of the San Juan Ridge on it. I'm really glad that we got this in here and we have a rope. That's Lassu going along here. And this is like the old ranches that they had down to lower elevations down here, Smartsville. And then this is the upper pastures up in the. . . This is kind of this area here of the Columbia Hill and Cusundry area. And this is Cam right here and Jake. And I don't know the names of their horses but I'm pretty sure that all of these cows got named at one time or another. So number five, this was a tapestry that Marcia wanted to do from the very beginning and it was so complicated because this consisted of 25 years of resistance to the mine. And the title of it is Don't Mine Our Water. People lost their water from their wells and that is depicted on the bottom. That when the mine starts everyone has water in their wells and then as the mine moves further along they'll lose their water, move further along, everybody's lost their water and there's a breakage because they hit an aquifer and then everything is flooded. This whole mine is flooded and they have to leave. So we have water that's also breaking this up into three parts and it's making this hourglass figure and they have the hourglass down here as well showing the time that's going by over 25 years. We turned our mascot of the 49er miner into a whistle-lower and I'm blanking on the owner's name of the mine. Anyways, Tim Callaway, we turned him into this mask bandit because he made a profit out of the loss. We've got our phone tree here, back when people actually used phone trees. There's a big fundraising everybody bringing in their various different kinds of art to sell, to raise money, to try to block the mine. This is to try to fit everybody who's been working on keeping the mine out into this one Board of Supervisors meeting. There were several different people who were on the Board of Supervisors at that time. There was Doc Dockler, Sam Dartig, and Gene Coward. I believe this was the beginning of the San Juan Rage Taxpayers Association, is that true? Yeah. Anyways, this one was really fun. I felt pretty good about it. This area right here, this was all of the letters and research that is kind of the unseen silent opposition. How do you show 25 years of effort that's put right there? People making tests, testing the water. What's the era of that particular depiction? From 1978 to 1985 was a big push. There were two different mine attempts. I feel it's not called Eugene's. I wish you could see the numbers on it. They are on, if you go and you see the actual tapestries it's written on there. The first one was proposing an open gift mine problem. He couldn't get his finance and so on. And then the second one, the mine proposed this underground drift mine through the grapples. The battle was always over water. They had a water hydrologist come and kept saying that the diggings were like a bathtub. They were going to have to pump the water out of the bathtub, but no water would come in from anywhere else. At the same time their geologist was napping all these faults that ran through the diggings and out. And in those faults was all of our water. So it wasn't until it actually came in that they dug into a fault that they flooded the mine completely and it was kind of exposed to the fraud. And they left. No one's started to do it since. And I think the recent decision on the rise mine probably is mining without account in this area where it's very. . . I mean there's lots of people who live on the ridge. I think we have like 3,000 people out there. So it's the real community and it's no more wild land than you could just go and dig a pan or whatever. Anyway. Yeah. The Kauffman's used to give free water to anybody. There was a spigot that was there right there with their friends that you could go and fill up their water tank and they lost their water. And when the water came back it was. . . I don't know if it was poison, but it was undrinkable. So the mining company was asked to drill new wells for everyone. And they drilled new wells but the water was filled with arsenic. What happens is that when they pulled the water out of the gravels it allowed oxygen to get in. And oxygen oxidized the gravels and released various chemicals from the arsenic. And to this day the school, the Grizzly Hill School, has to have bottled water. Yeah. This is another one that Marshall was really looking forward to making. The building of Oak Tree School. And there was wonderful photographs to use for reference for this. You look at all the details of all the people that are like mixing the cement and working. That all came from gorgeous black and white photographs. I don't know who photographed them. It was Hank Meals or somebody else. But that was such an amazing resource for me. But I still had to go out there and look at the whole overall campus to try to show what it would look like when it was just dirt. What it would look like when they were raising the walls and putting it in the insulation. And of course I had to stick some kids looking out the window because that's what I was doing while my parents were working weren't here. And along the bottom you'll see that it begins with the stained glass window of the river in 1975. And people planning. And then here there was the unions were picketing, crossing the picket line. This is Bruce. And these are some of the details of the buildings. And then it was burned down. It was arson. We lost our school. The devastation of that. And then rebuilding it. And then the same stained glass window became a phoenix rising from the ashes. And some of these things were never replaced. Like this was an amazing hand-carved door to the library that was a sun that had a little peak hole where you could look through. And then on the beams over here in the lodge. Like there were all these amazing details on the metal that were like drawings. This was all done by volunteers. We had two different metal workers. One did one side of the beam and the other one did the other. And they didn't match at all. Except in the bull holes. Well that was good. At least that happened. We have 250 people working on this. So you may see that this is the first one where the entire linen is covered with stitches. No linen is showing now. That's the progression. And they're starting to get really painterly. Like the way that they're using their threads is just amazing. Here we are with the river, which is a big reason why we all live here. We love this river. And Marshall was like, I don't think we should have any people in it. I think that they are really tired of stitching people. They're like, no more people. Please, no more people. And Marshall has a great idea that we should be looking underwater. So it's not just what you see when you go on your visit and you're walking on your own. But what is it like when you're swimming in it? And what would it be like to be an animal or be a fish? What would it look like? And so she kept having me make this deeper and deeper and deeper. Like this line going up and up and up and up and up and up. And then finally we arrived at this ratio, which just happens to be that this is a little bit wider than what the bottom part is on the other ones. So this little storyline here kind of becomes the storyline up here, which I think is really beautiful. So we've got all kinds of insects that are moving around. And we've got the otters, got trout, got made flies, got birds, dried flies. And this, if you're wondering, is just south of Herden Crossing. We also have on here a prayer for the salmon that we want the salmon to come back. We don't have salmon here now in this part of the river, but we hope that they come back. This is one of my favorites. Then we move on to the blue cradle. It was time to bring the linen back so that the series felt more integrated since so many of the tapas trees were just becoming heavy with all of this spread work. We wanted to bring the linens back. And I have the idea that the story could be told kind of like the squares on a baby blanket. And one of the amazing things about this blue cradle right here that Steve Sanfield made, there he is again, is that all the babies that ever slept in it, as it started being moved from family to family, all have their names written inside the cradle. And first it was on the headboard, and then it was on the footboard, and then it was on the sides. And I believe it's on the bottom now as well. And these are the names of all the babies that have been in it at the time that he made this tapas tree. There's now been more babies, so they're not included. But I just love this. 1968. Yeah, 1968. I was not in it. But all of my siblings were in it, and my son was in it. And right here, Rainy, Blue Cloud, Greensfelter, was in it, and both of her sons were in it. Okay, the Volunteer Fire Department. This is like one of the most important institutions of the San Juan Ridge, because living out in a rural area, you've got to know how to fight fire and jump in when you're needed. And originally this was just going to be one panel in the next tapestry in this one right here, but we realized that there was just way too much going on and that it needed to have its own tapestry. And so I believe this is Boy Johnson here, who's fire chief at one time. And I had a really good time with this. I went down to the fire department and I asked some of the firefighters if they would dress for me and show me how to use the tools and share photographs of fires that they've been on. And so I got to use a lot of their memorabilia to fill this in and see, get the accurate length of how you cut a fire line, a control one. And then we've got all these different things that the firefighters do besides fighting fire. And in between dividing them, we've got different firefighting tools to break it up. And then this is a fire hose. All right, here, this is the Scotchburn breakfast, which is the big annual one we've spent with firefighters. Super fun. What will this fire be part of the county? You can't really see it, but this is a bunch of kids that are all climbing around on the back of a fire track. So homesteads and work parties, this was another one. That was a very strong idea and it had a lot of different things that were mixed into it. There was all the different styles of housing from log cabins to yurts and school buses to, what do you call that, tempo framing? And what would you call Sam Dardy's house, other than like a spaceship? So he came from St. Louis, Missouri, and he was an architect originally. I just wonder if he was just trying to divide space like what is possible for wood to do. This is, is this a tile roof on Gary's place? This is a stone house over here. Now here, this is a cob house. So there's all these different types of buildings and it's that diversity that we wanted to celebrate. And we found that there was so many little details about each place that we, we couldn't just put one image. We needed to have like three images or four images in order to tell a story. So if you look closely at it, there's an outside border of color and that helps unify all the different images for one place. That's how you can follow the story around. But as you can see, we definitely could not fit the fire department on here. We barely fit in there, some work parties where these people are working on their driveway together. And let's see, there's some canning that's happening over here and some gardening, writing, meditating, painting. This is the only snowy scene until the very end. He's leaving. But like, how do we live? What is the way that we live out here? Then there's the idea of artists and artisans because there's so many people living on the San Juan Ridge who are some kind of artists or craftsmen. And it was a real challenge trying to get as many people on here as possible. Also was a challenge of not making people too small. We started off with, Mary said that I had to make them a certain size. They all had to be. It couldn't be too small. But by the time I got into the other side of the drawing, they were much smaller. So that just didn't work. But it ended up being okay because Marcia was horrified to realize that she'd forgotten several key people that they needed to somehow be put in there. So I had to go back and redraw this whole side and get it to match that side. So when you look at it this small, it's pretty chaotic. It's kind of, well, it's explosive. It's like explosive creativity. But again, I used the same idea from the Homesteads Tapestry to outline one whole area. So this yellow outline area is the visual artist. And then somewhere in here there's like photography. And then these are all the writers. And this is drama, dance. There's some woodworking, metalworking, potters, musicians. These are all real people. All of them. Past and present. Not everyone is still alive. I think we have a list, actually. Oh, I think Marcia actually has a list because this always comes up. Who is that? Am I included? And this is the last one. And it was such a joy after doing this one, which was so hard to finally get to do this one. It was just like a relief. There were some challenges in it because the San Juan Ridge stretches from about 1,500 feet elevation all the way up to 3,500 feet elevation, which is this is conifer forest and this is like a deciduous forest. So I had to figure out a way to kind of bend the landscape so I could get all of it in one image. Marcia had been complaining that there aren't enough nighttime images and she really wanted some more nighttime images. She really loved them. And then we realized also that there was like maybe two images of the wintertime. And so we knew that this had to be a nighttime winter scape of the forest and try to get as many little animals tucked in there and all different kinds of places that we could. We've got some raccoons and some deer and a chaff rabbit and a bobcat and a fox and an owl. There's one owl. I think this is a great moored owl and this is a solid owl. And then up here, hard to see, there's some ringtail, ringtail cats. And there's a moth. And way over there are some highways coming up at the moon and somewhere down here is a possum. And to get the subtlety of the shadows on the snow, Mary Moore was twisting like three threads to get this beautiful blended effect on the trunks and in the snow and show the difference between the icy water and the snow because everything is kind of monochromatic. So I made this sky very plain because I felt like this was so detailed that we needed this area to be simpler. But my dad, who had joined the embroiderers, I don't know how many tapestries back, he saw this and he goes, no, no, no, this is all wrong. You didn't do this right. So this is his take on the colors. It's the same color as when he turned it into kind of like this pink and purple starry starry night, which I think is really beautiful, really, really well done. Down here, in the lower elevations, there's just like a sprinkling of snow and then it gets thicker and thicker and thicker and thicker and thicker to get all the way up here. And that's the last one. So my part finished in January 2018 and then it was another four years of stitching before they finished all of the drawings that I made. So you know, at the Wild and Scenic Festival this year, the premiere is a documentary on the tapestry. My opponent, Gene Philly from Oakland, is called A Radical Thread and it opens on 13, 7 o'clock at that theater. You gotta get your ticket now. February 13th. February 13th. Yeah. Yeah. And the tapestries right now are housed here at the Armory Building in the Historic Society. That's where they're kept. The tapestry people had an archivist come up and show them how to protect these tapestries and how to keep them in storage with how to wrap them, and do all that because they would really like to see them last for 950 years. And the other side of that is that it's really hard to take eight people to put them up. And once they're up, you've got to be really careful that people want to get really close so they can see those faces and see that stitching, but we don't want them to touch. So it's this tug-of-war. You don't want to protect them too much because then that loses the spirit of them, but you do need to protect them. So Daniel suggested that the next time they're on exhibit in the county that we would put the notice in your newsletter and tell you where it is, and hope other people can see them in person because this is nothing compared to seeing them in person. Yes. Thank you, Jen. They are beautiful. Thank you. Yeah. Questions? Oh, yeah. Is there any questions? Can any of you speak to them? I can't. How you, your board or something that large? They made this table, this long, actually, I don't know if you can really call it a table. It's like two edges. A frame. Like a quilting frame. That's right. Okay. That at least 10 people could sit down at. Wow. And they could all be stitching at the same time. Cool. And they made it so that they could be taken down and moved as necessary. I think in the end, like during COVID, there was, there were like three different locations where people were stitching. So people couldn't stitch together anymore in that group, being right next to each other, but they were taken home by individuals and then traded. Yeah. Yeah. So you started with wool and then what the cotton was the silk? Yeah. Yeah. And I think by the end, they were using different kinds depending on how fine they wanted it to be or how vibrant they wanted it to be. Yeah. I don't know how much of a very final one was in silk, but I know that on the artists and artisans one that was quite a bit of silk because everything had to be so thin. They were like, I remember my dad, because he did a lot of faces and hands in that one because nobody else wanted to do that. And so he was splitting the embroidery to get it to be finer and finer to get this to just as fine as possible. Yeah. Yeah. How did you transfer your drawings to the letter? So typically what would happen is I would make a black and white drawing and then Mary Moore would tape it up on like a sliding glass door and then put the linen over it and then trace it. That way it's like this giant light board. Yeah. And then I would make a copy of the black and white drawing and I would do colored pencil on it as a kind of a leaping off point for them. They didn't have to follow it. They could make changes as they saw fit. But because I'm a painter and I know how things can change so much depending on what a color is next to that you can think that a color looks just right. And then you put another color next to it and now it looks wrong that I felt like they needed my eye with the color choices. Yes. Did you determine all the colors? Most of it. Yeah. Towards the end they were pretty much following my drawings but not always. Sometimes they would decide they wanted something to be different. Yes. How many hours a day would you draw? Just doing a little bit. It depended. Towards the end so there was a ton. Things sped up right around the time of the blue cradle. Steve Sandfield died and that kind of shocked us all and made us think about our mortality and that we needed to get all these designs done as soon as possible so that if any one of us passed away unexpectedly that everybody else would be able to continue on and finish the project. And so I just was doing them back to back to back to back trying to get them done as quickly as possible. But it still took me a couple of years beyond that. How did the stitches chosen? Did you audition people to know the quality of work? No. Anybody was welcome to come and to join and sometimes the tapestries would be out at like the Storytelling Festival and anybody who was there who wanted to sit down and put in a few stitches that they could. And it was more about like, how did you like hanging out with the other people who were embroidering? Because it would take a long time and you're just sitting around there for hours so you better like each other. There was a core group that we met once a week. Twice a week sometimes. Twice a week sometimes. The sister who stitched about an inch. The schoolhouse. Okay, yes. Any idea how many miles of thread? I don't know. Probably, you know, to the moon and back. Any other questions? Any other idea how many people actually stitched on it? We do have that number somewhere. Something like 150, something like that. Some of them are kids. Yeah, but the names of everyone who stitched on a tapestry are on a separate piece of linen that is attached to the back. So you can see who was part of that. Any other questions? Sure. Welcome round of applause.

So anyway, thank you for coming to this show. We just, on Tuesday, Jen and I did a presentation to the Board of Supervisors, and the tapestry project was designated as the cultural resource of the county. The first designation of the year, we put on a very short program with them. We got 10 minutes, which was really generous of them in their busy schedule. So, and then my friend Bernie Zimmerman from the Landmark Commission, I'm a member of the Landmark Commission, suggested to Daniel that we ought to do a presentation here. And of course, you always volunteer when Bernie asks you to do something. And Jen, I'm not part of the tapestry project, but my office is in the North Columbia Schoolhouse, and I've been there for 50 years, and I am sort of involved in everything that happens up there and somewhere and another. And so I've been through the Landmark Commission, and then the tapestry committee that kind of is shepherding this project through. I've taken on this role of trying to speak to all of you. The tapestries consist of 12 tapestries. They covered the history of the San Juan Ridge. They were originated by Marcia Stone, who is a textile artist from the ridge, a longtime artist and resident. And she had the idea that somehow she wanted to convey the recent back-to-the-land history of San Juan Ridge, because there's a lot of different stories about the San Juan Ridge. And so she wanted to get that in a form that could be shared with the community and the rest of the county. And in researching that, she discovered the Bayou tapestries, which chronicle the Battle of Hastings back in 1066. It still exists. It's 950 years old. It's on display in Bayou, France. It's an incredible tapestry. It's 224 feet long. It was designed to go around the walls, the high walls of a cathedral in Bayou. And they would display it maybe once a year, twice a year, and then it would go into storage. And the techniques and the colors of how the Bayou tapestry was done, Marcia decided that that was something that would be a great medium for telling this story. And so they started in 2007. There's been over 10,000 hours put into doing embroidery on these 12 tapestries. Now tapestries are generally woven, and then there's this kind of generic, kind of like the word aspirin, that covers wall hangings. But this is an embroidered, all these tapestries are embroidered, which means skidges and knots, very finely done with needles. All their name would be needlework, and sometimes the Bayou tapestry is now called the Bayou embroidery. So it's following in that tradition. In the beginning it was limited to the eight colors that were used in the Bayou tapestry. And then as all these people came to work on it over the years, the creative juices of the ridge, it expanded. And some of the detail, they needed more colors. Jen's going to go through all of this. But when you see like the last, excuse me, I'm losing my voice, I always do, and you'll see the progression from something that was similar to the Bayou to something that is kind of fantastic art. So I wanted to start with a little bit of history, and this is more like history from eighth grade. So this is a little bit of history of the battle of Hastings in 1066. And that was a war between the King of England. He was an Anglo-Saxon named Harold God's Windson, who usurped the throne after King Edward died without a successor. And William the Duke of Normandy said that he had been told that he would be the King of England. But Harold took the throne, so William decided to invade England. And the Normans of France were descended from Vikings, and they assimilated into this kind of French culture in Normandy. So he invaded, and there were skirmishes in 1066. It culminated in the Battle of Hastings, where the English were defeated. There was maybe a thousand, they don't really know how many knights and soldiers and cavalry they had, but it was probably about a thousand army people on each side. And during that, Harold was killed. This is a little snippet from the 224 feet. And there's a lot of controversy over how he was killed. And current thinking is that it wasn't an arrow to the eye, which is what this depicts, but really gruesome, typical medieval hacking somebody to death. Anyway, this is just an example, and the thing you'll notice here is that the linen background, this is a woven linen, is exposed. It's the background, and the only things that are embroidered are the figures, lines, and some fill in some of the animals and the figures. And then at the bottom, there's these little things that kind of detail different parts of the battle. That ended after it took another three years for William the Conqueror, he became William the Conqueror, to subjugate the rest of England. And that was the last invasion in England. It hasn't been invaded successfully since. There's been some excursions, but nothing much. So, I think that's really about all I need to say on that. Oh, I should mention that it's a linen background, and Xanwong Tapestry uses the same linen background, and wool yards, that's how it was started. And those colors that they had back then were russet, blue-green, gold, olive-green, dark-blue, black, sage-green, and blue, just eight colors. And you'll see that when Xanwong gets into the tapestries. So, I'd like to turn it over to Xanwong. Xanwong is the artist that did the backgrounds for the tapestries, and she's been involved in the project from the very beginning. Hi, everybody. Nice to see you. Jennifer Rayne Crosby, and I grew up on Xanwong Ridge. I moved out there in 1875, and I was five years old. Marcia invited me onto this project in 2006, and I didn't know if I could do it, because it was so huge. I'd illustrated books before, and flyers, and small projects, and each one of these drawings was 30 inches tall and at least six feet wide. And so it was very intimidating, but it was also very, very exciting. I liked her idea of sharing the history of the ridge from her vision of the people that moved there, and also people that were living there, mixing together, and then the things that we value that would carry that forward and remember what's important to us. So, when she saw the Bayou Tapestry, this is how I remember it, is that she saw this book, and it hit her that this was something that people made, and that we could do something similar, that anybody could just start stitching this. And so she asked what kind of lids were used in the Bayou Tapestry, and so threads were used in the Bayou Tapestry, and she brought them together, too. Come on, work for me. This is going to go all the way into the future, isn't it? Oh my God, number seven at least now. Okay. I can just sit next slide. So, in this first one, we had this huge enormous list of all the different stories that we wanted to tell. There was, like, so many, and we couldn't decide which one to start with, and so I volunteered that what we should do is start with this local ceremony that happens out in the woods that I'd been going to since I was a little girl. Like, I could just dive into this while we were figuring out what the chronology of all of the stories was going to be, and I could use my memories, and I knew who I should talk to to find photographs and to corroborate our stories, and so it goes from left to right, and it begins over in the left-hand side with everyone parking in a meadow and then walking up this steep hill up onto this ridge top, and then the circles in the middle are depicting different ceremonies that happen on that day, and on the far right is the end of the day when we're having picnic underneath the tree, and there's a volleyball game, and there's music around the bonfire, and along the bottom, you'll see, let's see, does this work here? Along the bottom, you'll see that just like the Bay of Tapestry, there's another storyline happening, and so there are the things that are happening before. Each of the ceremonies, this right here is the Government Parade, there's the Arrows Ceremony, that's the offering of cornmeal, people speaking from the heart, and then saying goodbye and everybody going home. But there's all of these different stories following the Bay of Tapestry. There's also this border on the top, and so we have three main sections. We have this main area here, which is like the central theme for our story, and then we have this long one on the bottom, which is like telling more details about the story, and then this one here only appears on this one. It moves down into this area on all the rest of it, the dividing area between the thick and the thin. This tapestry is 12 feet long, just to give you a perspective. And it's right underneath his office. And it's two pieces, right? I think it was actually three pieces because it was so long that I didn't have a space where I could draw something that long. But it was problematic trying to figure out how to bring those pieces together and have it be continuous and not have any kind of break in the lines, and so we quickly moved to one of these six foot long tapestries, where we could do it all in one piece. So we knew that the second one had to be the North Columbia Schoolhouse Cultural Center because this was the inspiration for where we wanted the tapestries to live and it was one of the first places where our community really started to feel itself. They worked with the Coughlin family who owns the building and the land and asked if they could have a cultural center there and then they worked together to make that happen. And you can see that right here. People are making the amphitheater, which is also over here. And then you start seeing these little scenes along the bottom that are all the different kinds of events. And there's so many events that they had to go up here in these little vans as well. And then like the biggest event that still happens there today is this year's Tourism Festival and we have Steve Sanfield upon the stage because he started it all. It was his grand idea. And along here is this border of many hands because the making of the cultural center, the amphitheater, the ongoing volunteerism is the work of many hands. There's been lots of programs in the schoolhouse. Yeah. Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Steve Sanfield, lots of music and it's still very vibrant. So you can see that the colors have changed. That we were being very close to the bayou tapestry as close as we possibly could. The threads were a lot thicker. And then here it started moving into brighter colors and a big voice and anchor for moving forward. Anchor for moving forward, that's kind of interesting. The driving force for moving forward was our lead stitcher, Mary Moore. And right up here is the Balinese dancers who come out there every year and just could not do their costumes with the bayou colors. You need to have bright paint and bright purple. And so it started to move right there. Of course Mary loves color and so it was going to move pretty fast into the third tapestry. This is a six foot one. This is another six foot one. So the six foot tapestries fit exactly between the windows. So if we go back here, you can kind of see the building. So inside of the building in between those windows is six foot tapestries. And in this one, Marcia wanted to tell the story of the gold rush in a way that had never been seen before. And she had seen these paintings by my new artist Frank Day and was really, really moved by his depictions of whirlwinds. And she thought whirlwind would be a pretty good metaphor for the gold rush. That everything got stirred up and moved somewhere else. And so on this side, this is how she imagined the land before. This is the gold rush. And on this side is what we know the land looks like now. And under here, this is all the animals and plants before. And these are all the animals and plants that are here now. And there's this lovely little spot down here where you have this magnifying glass and these sundews because the sundews are out there in the days if you go looking for them. And this ropey pattern is like time. You imagine that time is a rope. So this is one of my favorite ones. I just feel like I loved her idea of the fiery whirlwind and I had a really great time drawing everything just tumbling through the air. So this is a really fun one to look at if you're able to see it in person. So this is the fourth one that I illustrated. And it's the cattle drive and it shows the building across. So over here, kind of off-screen is where the cultural center stands and this is the Coughlin's ranch house. And Marcia really wanted to work on Don't Find Our Water which ended up being number five but I felt like we weren't ready for that so we worked on this one. And again, I used my memories of being on Tylerfoot Road and being marooned by cows. And I was one of these kids on the school bus where we were all trying to touch the cows and I was also in this little VW bug with a barking dog and I just thought it was wonderful. This is the only tapestry that has a map of the San Juan Ridge on it. I'm really glad that we got this in here and we have a rope. That's Lassu going along here. And this is like the old ranches that they had down to lower elevations down here, Smartsville. And then this is the upper pastures up in the. . . This is kind of this area here of the Columbia Hill and Cusundry area. And this is Cam right here and Jake. And I don't know the names of their horses but I'm pretty sure that all of these cows got named at one time or another. So number five, this was a tapestry that Marcia wanted to do from the very beginning and it was so complicated because this consisted of 25 years of resistance to the mine. And the title of it is Don't Mine Our Water. People lost their water from their wells and that is depicted on the bottom. That when the mine starts everyone has water in their wells and then as the mine moves further along they'll lose their water, move further along, everybody's lost their water and there's a breakage because they hit an aquifer and then everything is flooded. This whole mine is flooded and they have to leave. So we have water that's also breaking this up into three parts and it's making this hourglass figure and they have the hourglass down here as well showing the time that's going by over 25 years. We turned our mascot of the 49er miner into a whistle-lower and I'm blanking on the owner's name of the mine. Anyways, Tim Callaway, we turned him into this mask bandit because he made a profit out of the loss. We've got our phone tree here, back when people actually used phone trees. There's a big fundraising everybody bringing in their various different kinds of art to sell, to raise money, to try to block the mine. This is to try to fit everybody who's been working on keeping the mine out into this one Board of Supervisors meeting. There were several different people who were on the Board of Supervisors at that time. There was Doc Dockler, Sam Dartig, and Gene Coward. I believe this was the beginning of the San Juan Rage Taxpayers Association, is that true? Yeah. Anyways, this one was really fun. I felt pretty good about it. This area right here, this was all of the letters and research that is kind of the unseen silent opposition. How do you show 25 years of effort that's put right there? People making tests, testing the water. What's the era of that particular depiction? From 1978 to 1985 was a big push. There were two different mine attempts. I feel it's not called Eugene's. I wish you could see the numbers on it. They are on, if you go and you see the actual tapestries it's written on there. The first one was proposing an open gift mine problem. He couldn't get his finance and so on. And then the second one, the mine proposed this underground drift mine through the grapples. The battle was always over water. They had a water hydrologist come and kept saying that the diggings were like a bathtub. They were going to have to pump the water out of the bathtub, but no water would come in from anywhere else. At the same time their geologist was napping all these faults that ran through the diggings and out. And in those faults was all of our water. So it wasn't until it actually came in that they dug into a fault that they flooded the mine completely and it was kind of exposed to the fraud. And they left. No one's started to do it since. And I think the recent decision on the rise mine probably is mining without account in this area where it's very. . . I mean there's lots of people who live on the ridge. I think we have like 3,000 people out there. So it's the real community and it's no more wild land than you could just go and dig a pan or whatever. Anyway. Yeah. The Kauffman's used to give free water to anybody. There was a spigot that was there right there with their friends that you could go and fill up their water tank and they lost their water. And when the water came back it was. . . I don't know if it was poison, but it was undrinkable. So the mining company was asked to drill new wells for everyone. And they drilled new wells but the water was filled with arsenic. What happens is that when they pulled the water out of the gravels it allowed oxygen to get in. And oxygen oxidized the gravels and released various chemicals from the arsenic. And to this day the school, the Grizzly Hill School, has to have bottled water. Yeah. This is another one that Marshall was really looking forward to making. The building of Oak Tree School. And there was wonderful photographs to use for reference for this. You look at all the details of all the people that are like mixing the cement and working. That all came from gorgeous black and white photographs. I don't know who photographed them. It was Hank Meals or somebody else. But that was such an amazing resource for me. But I still had to go out there and look at the whole overall campus to try to show what it would look like when it was just dirt. What it would look like when they were raising the walls and putting it in the insulation. And of course I had to stick some kids looking out the window because that's what I was doing while my parents were working weren't here. And along the bottom you'll see that it begins with the stained glass window of the river in 1975. And people planning. And then here there was the unions were picketing, crossing the picket line. This is Bruce. And these are some of the details of the buildings. And then it was burned down. It was arson. We lost our school. The devastation of that. And then rebuilding it. And then the same stained glass window became a phoenix rising from the ashes. And some of these things were never replaced. Like this was an amazing hand-carved door to the library that was a sun that had a little peak hole where you could look through. And then on the beams over here in the lodge. Like there were all these amazing details on the metal that were like drawings. This was all done by volunteers. We had two different metal workers. One did one side of the beam and the other one did the other. And they didn't match at all. Except in the bull holes. Well that was good. At least that happened. We have 250 people working on this. So you may see that this is the first one where the entire linen is covered with stitches. No linen is showing now. That's the progression. And they're starting to get really painterly. Like the way that they're using their threads is just amazing. Here we are with the river, which is a big reason why we all live here. We love this river. And Marshall was like, I don't think we should have any people in it. I think that they are really tired of stitching people. They're like, no more people. Please, no more people. And Marshall has a great idea that we should be looking underwater. So it's not just what you see when you go on your visit and you're walking on your own. But what is it like when you're swimming in it? And what would it be like to be an animal or be a fish? What would it look like? And so she kept having me make this deeper and deeper and deeper. Like this line going up and up and up and up and up and up. And then finally we arrived at this ratio, which just happens to be that this is a little bit wider than what the bottom part is on the other ones. So this little storyline here kind of becomes the storyline up here, which I think is really beautiful. So we've got all kinds of insects that are moving around. And we've got the otters, got trout, got made flies, got birds, dried flies. And this, if you're wondering, is just south of Herden Crossing. We also have on here a prayer for the salmon that we want the salmon to come back. We don't have salmon here now in this part of the river, but we hope that they come back. This is one of my favorites. Then we move on to the blue cradle. It was time to bring the linen back so that the series felt more integrated since so many of the tapas trees were just becoming heavy with all of this spread work. We wanted to bring the linens back. And I have the idea that the story could be told kind of like the squares on a baby blanket. And one of the amazing things about this blue cradle right here that Steve Sanfield made, there he is again, is that all the babies that ever slept in it, as it started being moved from family to family, all have their names written inside the cradle. And first it was on the headboard, and then it was on the footboard, and then it was on the sides. And I believe it's on the bottom now as well. And these are the names of all the babies that have been in it at the time that he made this tapas tree. There's now been more babies, so they're not included. But I just love this. 1968. Yeah, 1968. I was not in it. But all of my siblings were in it, and my son was in it. And right here, Rainy, Blue Cloud, Greensfelter, was in it, and both of her sons were in it. Okay, the Volunteer Fire Department. This is like one of the most important institutions of the San Juan Ridge, because living out in a rural area, you've got to know how to fight fire and jump in when you're needed. And originally this was just going to be one panel in the next tapestry in this one right here, but we realized that there was just way too much going on and that it needed to have its own tapestry. And so I believe this is Boy Johnson here, who's fire chief at one time. And I had a really good time with this. I went down to the fire department and I asked some of the firefighters if they would dress for me and show me how to use the tools and share photographs of fires that they've been on. And so I got to use a lot of their memorabilia to fill this in and see, get the accurate length of how you cut a fire line, a control one. And then we've got all these different things that the firefighters do besides fighting fire. And in between dividing them, we've got different firefighting tools to break it up. And then this is a fire hose. All right, here, this is the Scotchburn breakfast, which is the big annual one we've spent with firefighters. Super fun. What will this fire be part of the county? You can't really see it, but this is a bunch of kids that are all climbing around on the back of a fire track. So homesteads and work parties, this was another one. That was a very strong idea and it had a lot of different things that were mixed into it. There was all the different styles of housing from log cabins to yurts and school buses to, what do you call that, tempo framing? And what would you call Sam Dardy's house, other than like a spaceship? So he came from St. Louis, Missouri, and he was an architect originally. I just wonder if he was just trying to divide space like what is possible for wood to do. This is, is this a tile roof on Gary's place? This is a stone house over here. Now here, this is a cob house. So there's all these different types of buildings and it's that diversity that we wanted to celebrate. And we found that there was so many little details about each place that we, we couldn't just put one image. We needed to have like three images or four images in order to tell a story. So if you look closely at it, there's an outside border of color and that helps unify all the different images for one place. That's how you can follow the story around. But as you can see, we definitely could not fit the fire department on here. We barely fit in there, some work parties where these people are working on their driveway together. And let's see, there's some canning that's happening over here and some gardening, writing, meditating, painting. This is the only snowy scene until the very end. He's leaving. But like, how do we live? What is the way that we live out here? Then there's the idea of artists and artisans because there's so many people living on the San Juan Ridge who are some kind of artists or craftsmen. And it was a real challenge trying to get as many people on here as possible. Also was a challenge of not making people too small. We started off with, Mary said that I had to make them a certain size. They all had to be. It couldn't be too small. But by the time I got into the other side of the drawing, they were much smaller. So that just didn't work. But it ended up being okay because Marcia was horrified to realize that she'd forgotten several key people that they needed to somehow be put in there. So I had to go back and redraw this whole side and get it to match that side. So when you look at it this small, it's pretty chaotic. It's kind of, well, it's explosive. It's like explosive creativity. But again, I used the same idea from the Homesteads Tapestry to outline one whole area. So this yellow outline area is the visual artist. And then somewhere in here there's like photography. And then these are all the writers. And this is drama, dance. There's some woodworking, metalworking, potters, musicians. These are all real people. All of them. Past and present. Not everyone is still alive. I think we have a list, actually. Oh, I think Marcia actually has a list because this always comes up. Who is that? Am I included? And this is the last one. And it was such a joy after doing this one, which was so hard to finally get to do this one. It was just like a relief. There were some challenges in it because the San Juan Ridge stretches from about 1,500 feet elevation all the way up to 3,500 feet elevation, which is this is conifer forest and this is like a deciduous forest. So I had to figure out a way to kind of bend the landscape so I could get all of it in one image. Marcia had been complaining that there aren't enough nighttime images and she really wanted some more nighttime images. She really loved them. And then we realized also that there was like maybe two images of the wintertime. And so we knew that this had to be a nighttime winter scape of the forest and try to get as many little animals tucked in there and all different kinds of places that we could. We've got some raccoons and some deer and a chaff rabbit and a bobcat and a fox and an owl. There's one owl. I think this is a great moored owl and this is a solid owl. And then up here, hard to see, there's some ringtail, ringtail cats. And there's a moth. And way over there are some highways coming up at the moon and somewhere down here is a possum. And to get the subtlety of the shadows on the snow, Mary Moore was twisting like three threads to get this beautiful blended effect on the trunks and in the snow and show the difference between the icy water and the snow because everything is kind of monochromatic. So I made this sky very plain because I felt like this was so detailed that we needed this area to be simpler. But my dad, who had joined the embroiderers, I don't know how many tapestries back, he saw this and he goes, no, no, no, this is all wrong. You didn't do this right. So this is his take on the colors. It's the same color as when he turned it into kind of like this pink and purple starry starry night, which I think is really beautiful, really, really well done. Down here, in the lower elevations, there's just like a sprinkling of snow and then it gets thicker and thicker and thicker and thicker and thicker to get all the way up here. And that's the last one. So my part finished in January 2018 and then it was another four years of stitching before they finished all of the drawings that I made. So you know, at the Wild and Scenic Festival this year, the premiere is a documentary on the tapestry. My opponent, Gene Philly from Oakland, is called A Radical Thread and it opens on 13, 7 o'clock at that theater. You gotta get your ticket now. February 13th. February 13th. Yeah. Yeah. And the tapestries right now are housed here at the Armory Building in the Historic Society. That's where they're kept. The tapestry people had an archivist come up and show them how to protect these tapestries and how to keep them in storage with how to wrap them, and do all that because they would really like to see them last for 950 years. And the other side of that is that it's really hard to take eight people to put them up. And once they're up, you've got to be really careful that people want to get really close so they can see those faces and see that stitching, but we don't want them to touch. So it's this tug-of-war. You don't want to protect them too much because then that loses the spirit of them, but you do need to protect them. So Daniel suggested that the next time they're on exhibit in the county that we would put the notice in your newsletter and tell you where it is, and hope other people can see them in person because this is nothing compared to seeing them in person. Yes. Thank you, Jen. They are beautiful. Thank you. Yeah. Questions? Oh, yeah. Is there any questions? Can any of you speak to them? I can't. How you, your board or something that large? They made this table, this long, actually, I don't know if you can really call it a table. It's like two edges. A frame. Like a quilting frame. That's right. Okay. That at least 10 people could sit down at. Wow. And they could all be stitching at the same time. Cool. And they made it so that they could be taken down and moved as necessary. I think in the end, like during COVID, there was, there were like three different locations where people were stitching. So people couldn't stitch together anymore in that group, being right next to each other, but they were taken home by individuals and then traded. Yeah. Yeah. So you started with wool and then what the cotton was the silk? Yeah. Yeah. And I think by the end, they were using different kinds depending on how fine they wanted it to be or how vibrant they wanted it to be. Yeah. I don't know how much of a very final one was in silk, but I know that on the artists and artisans one that was quite a bit of silk because everything had to be so thin. They were like, I remember my dad, because he did a lot of faces and hands in that one because nobody else wanted to do that. And so he was splitting the embroidery to get it to be finer and finer to get this to just as fine as possible. Yeah. Yeah. How did you transfer your drawings to the letter? So typically what would happen is I would make a black and white drawing and then Mary Moore would tape it up on like a sliding glass door and then put the linen over it and then trace it. That way it's like this giant light board. Yeah. And then I would make a copy of the black and white drawing and I would do colored pencil on it as a kind of a leaping off point for them. They didn't have to follow it. They could make changes as they saw fit. But because I'm a painter and I know how things can change so much depending on what a color is next to that you can think that a color looks just right. And then you put another color next to it and now it looks wrong that I felt like they needed my eye with the color choices. Yes. Did you determine all the colors? Most of it. Yeah. Towards the end they were pretty much following my drawings but not always. Sometimes they would decide they wanted something to be different. Yes. How many hours a day would you draw? Just doing a little bit. It depended. Towards the end so there was a ton. Things sped up right around the time of the blue cradle. Steve Sandfield died and that kind of shocked us all and made us think about our mortality and that we needed to get all these designs done as soon as possible so that if any one of us passed away unexpectedly that everybody else would be able to continue on and finish the project. And so I just was doing them back to back to back to back trying to get them done as quickly as possible. But it still took me a couple of years beyond that. How did the stitches chosen? Did you audition people to know the quality of work? No. Anybody was welcome to come and to join and sometimes the tapestries would be out at like the Storytelling Festival and anybody who was there who wanted to sit down and put in a few stitches that they could. And it was more about like, how did you like hanging out with the other people who were embroidering? Because it would take a long time and you're just sitting around there for hours so you better like each other. There was a core group that we met once a week. Twice a week sometimes. Twice a week sometimes. The sister who stitched about an inch. The schoolhouse. Okay, yes. Any idea how many miles of thread? I don't know. Probably, you know, to the moon and back. Any other questions? Any other idea how many people actually stitched on it? We do have that number somewhere. Something like 150, something like that. Some of them are kids. Yeah, but the names of everyone who stitched on a tapestry are on a separate piece of linen that is attached to the back. So you can see who was part of that. Any other questions? Sure. Welcome round of applause.

Zoom Out

Zoom In (Please allow time for high-res images to load)

Zoom: 100%