Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2025-03-20 - We Are Not Strangers Here - African American Histories in Rural California with Susan D. Anderson (72 minutes)

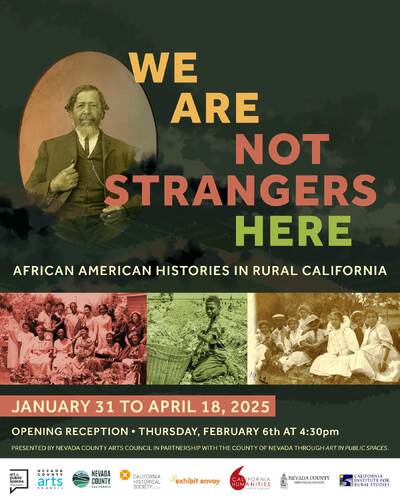

During the Gold Rush and continuing through today, Californians have been part and parcel of rural areas. While it is widely recognized that many Black people who migrated to California moved into booming cities, African Americans are not strangers to rural California. Rural Black residents opened schools, worked the land, and exercised vigilance about the equal rights of citizens. Over successive migrations in the 19th-and 20th-centuries, generations settled in agricultural and rural areas from as far north as Siskiyou County, here in Nevada County, to the Central Valley and the Imperial Valley in the South. Please join us for a lively evening with Susan D. Anderson, History Curator and Program Manager at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. Susan is an accomplished and highly respected public historian of the African American history of California and the West, whose research culminated in the creation of the exhibit We Are Not Strangers Here: African American Histories in Rural California. Now on display at the Rood Center, and open through April 18th, the exhibit is sponsored by the Nevada County Arts Council's Art in Public Spaces Program in partnership with the Nevada County Historical Society, Nevada County and through a generous gift from Floyd and Judy Sam.

Author: Susan D. Anderson

Published: March 20, 2025

Original Held At:

Published: March 20, 2025

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

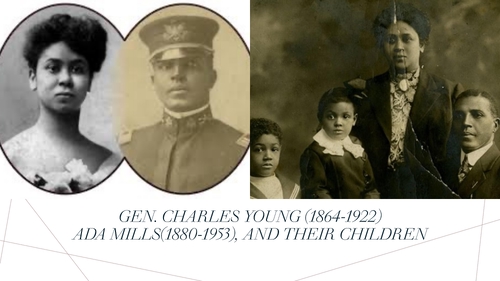

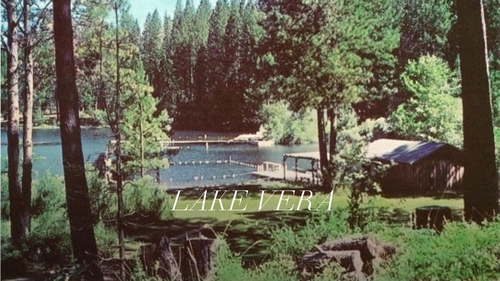

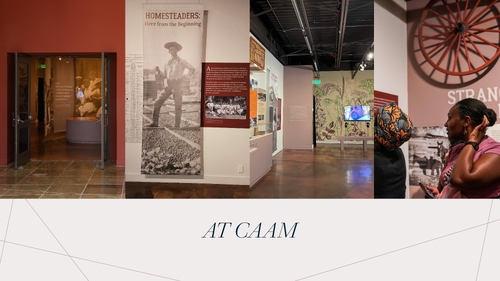

Good evening everybody. I'm really pleased to be able to introduce Susan Anderson, but that will take just a minute. She's such an accomplished person, but I want to just also give a hand wave and thank Hannah Mosby for coming and us with the Nevada County Arts Council and it is through her organization's auspices that we were able to bring this amazing exhibit to the Roots Center. So thank you Hannah, Analyze a Tutor, and all the folks that made that happen. Yes, so thank you. Is there anybody in the audience that's a member of the Godaire family? No, too bad. So a member of one of the families that we featured in the exhibit wandered into the exhibit and so identified, but somehow we never got that person's email or she didn't get mine, so I'm still waiting and hoping that the family member will come eventually. So Susan Anderson is probably, well I would say the most accomplished public historian in California studying African American topics. She's a speaker, an author, collections curator, exhibit developer. She developed the We Are Not Strangers here exhibit. She is the history curator and program manager at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, but she has been at or helped develop almost all of the major collections in California at the Bankrupt. You see USC and just just about everywhere. So I think she is a treasure and we're really delighted she's here. She has a little bit of a Nevada County Connection, but I'll let her tell you about that. So if you haven't been to the exhibit, it's until April 18th, but in the meantime, I think you're going to see a lot of what you might need to know about the exhibit and I hope that will motivate you to go. So Susan, are you ready? All right. Okay. Well, good evening, everyone. Let me figure this out. I have to be able to see the slides. So, well, I love historical societies and I really feel that I'm with my people when I'm around historical societies. As a researcher, I need historical societies. History, all history is local history and we live in a kind of a funny culture because certainly in the academic world, there's a kind of prejudice against what they call regional history. And if you go to a local college or university, you're rarely going to find historians of the area or even California. A lot of historians, if you go to the University of California campus or even in Cal State campus and sometimes community college campus, they studied the South, they studied the British colonies, they studied what people call the master narratives, but California and the West and what they consider local history is always take a back seat. So the work that you do is so vital because it's where we go to find out what really happened. I want to thank the Nevada County Arts Council, the Nevada County Historical Society, and the County of Addis Art and Public Places for having me this evening. Let me get used to what I have to do here. Okay, so I think what we're going to do this evening is I'm going to talk a little bit about the inspiration for the exhibition that's in the Rood Center and a little bit about the work that I do. Then I'm going to tell a couple of stories from the exhibition about families that we looked at from around California. And then I'll mention a section of the exhibition that deals with independent black settlements in early California history. Then my friend and my colleague Linda Jack is going to come up because one of the exciting things about this traveling version of this exhibition is that in local areas, historians are supplementing the exhibit with local stories and that's what we want. We really want to widen that circle and start really restoring these stories because the stories were there. There are a lot of historians that overlooked them, but these people and these stories and these events were they were there to be found all along. And then we hope to open it up to questions and have a discussion with each other. So I also, before really getting into the meat of things, I really want to extend special thanks to Linda Jack of the Nevada County Historical Society. She's really the reason that I'm here and that probably we're here tonight. And if you don't mind, Linda probably knows the significance of these images, but if you don't mind, I'm just going to tell you a little story about how I met her. What you're looking at are on the left pictures of Captain Charles Young and his wife Aida Mills and this is probably these pictures will probably take it around the time they met when he was stationed in the San Francisco Presidio in 1903. And then the other picture on the other side is the family quite a few years later and with their two children Charles and Marie, Charles and Marie, they actually gave them French names. And I was invited way back in 2017, I think it was, to be on the National Park Service Buffalo Soldiers Scholars Roundtable. There were about five scholars and about 40 park staff people who came to this. It was in San Francisco. And I was researching Charles Young's years at the Presidio. He had this remarkable eventful time when he was sent there. He was the commander of the ninth cavalry, what people now call Buffalo Soldiers. He became superintendent of what is now Sequoia and King's Canyon National Park. And he in the ninth cavalry and people who lived in Tulare County who worked on the crews, the rows that they built that summer are still in use in Sequoia National Park. And he was especially received special commendation for the job that he did in such a short period of time. He lectured at Stanford, which was really a remarkable thing because military men didn't make public speeches at that time. And he gave this amazing speech that we have copies of where he ends. He's addressing Jim Crow, which was at its in most intense period during 1903. And he says at the end of his speech at Stanford, just give us a white man's chance. And one of the other things he did during this same year of being stationed in the Presidio was the ninth cavalry was personally invited by President Teddy Roosevelt to escort him when he came to San Francisco and paraded down Market Street in the financial district. And it was the first time there was a black escort for a US president. But Teddy Roosevelt knew the ninth Calvary knew Charles Young personally because to tell you the truth, they saved him and the rough riders in Cuba when they charged San Juan Hill. So there was this amazing story to tell about this time in California and the fact that California offered these kind of opportunities to a military man like this. And I'm reading about him and I read an historical newspaper that said that he also got married. What a year he had. And the woman that he married was from Brass Valley. So I started really digging around and trying to find out more about Aida Mills. And I found the website of the Nevada County Historical Society and somehow, you know, one thing leads to another and somehow found Linda. And this was 2017, so that's when we met. And you just started throwing things at me. And because you already knew in depth about her family. And I'm hoping that something that I'm working on will reflect the depth of your research because there's been some things written about Charles Young. He said national importance because he was the highest ranking black officer in the United States Army and he was forced to retire before World War I because that was the time the US Army was ready to have a black general. And the investigation was done. And in 2023, the Secretary of the Army gave him a posthumous promotion to Brigadier General. So you can see how regional history, there's no such thing as regional history. Regional history, national history, it's all the same in a home girl like Aida Mills can end up having national impact, which she did. I also want to say what a delight it is for me to return to this area where I spent my summers growing up. I was a bluebird and a campfire girl, which we was called camp, now it's just called campfire. It's genderless now. A campfire girl from the time I was in second grade until I graduated from high school. I was a camper at the campfire girl's camp on Lake Vera Camp Celio every summer. So was my sister. And my involvement didn't stop there. When I was in high school, I was a counselor in training. And I made some lifelong friends and there's about four of us. It was a small group in their store that are still in touch. And if I tell you how long ago I was in my school, you would really be impressed by how long we sustained our relationship. And then the last summer before I went away to college, I was actually a counselor at Camp Celio and spent the whole summer there, very daring. And on our days off in between camp sessions, we used to go camp on the banks of the Trekkie River and go skiing and dipping and things like that. My things my parents never knew. So in many ways, you know, making the drive of Highway 49 and coming here to this beautiful place and seeing the native black oaks and the pines and the firmer trees is like coming home. Let's see, I'm going to have a little water. And there we go. Now I want to expand on what I was talking about about being a camper and living in the mountains, because it's actually very much related to the theme of the exhibit that's at the Root Center right now. The title of the exhibition is We Are Not Strangers Here, African Americans in Histories in Rural California. And this has had that working on the exhibition, which opened, I'll be showing you some some pictures from the gallery exhibition that we did at my museum. It's had a personal resonance for me, because my brother and sister and I grew up spending a lot of time in wilderness. So I went ahead actually and stuck these images of my parents here. These both of my parents have passed away. And these are pictures of them when they were very young. Actually on the right, my father Bill, that was my parents wedding day. And the picture on the left is a little before, because that dress my mother is wearing looks more 40s than 50s, doesn't it? Anybody who's aware of comics? But they're very close together. And part of the reason we spent a lot of time in wilderness, it wasn't just going to camp for a week or two every summer. My father was a hunter and he was a fisher. And so we used to take family trips throughout the year, because you don't hunt in summer, you hunt their seasons. And we were always going up to Redwood Country. And we were always going up to the Russian River. And we were always meeting other families who were hunting and fishing. And we always had venison and rabbit in our deep frees at home. And so in addition to what we were doing at camp and camp for our girl activities, I was my mother made me join the Sierra Club. And I was going on backpack trips on the John Your trail in Yosemite. And my dad was a gardener. And we ate all of our produce out of that garden. We had artichokes and strawberries and onions and tomatoes and my mother canned and preserved from that garden. So we were accustomed to eating the fruit of the earth and being close to the earth. And so as I was saying, the theme of the exhibit has a personal resonance for me. I took the title from an essay by Ravi Howard, who's a wonderful writer. And he had an essay in a book of poetry that was published a few years ago called Black Nature. And he refutes these assumptions that black people are separated from nature. One of the things he said was at some point, the terms urban and black became interchangeable. Such terminology would help us believe that our history began in cities, and that we are people of concrete and bricks far removed from the Oaks rivers and low country. So of course, that doesn't make sense. When you have centuries of a people who are confined to agricultural work in a system of enslavement. So that's number one. When people started migrating to California, especially in large numbers during the Gold Rush, including African-Americans, the largest, first large voluntary migration of African-Americans in the United States occurred as part of the Gold Rush, the California Gold Rush. They were going to the Gold Fields like everybody else. They were here in Nevada County, and they were throughout the mother load from all the way from the northern tip of El Dorado County down to Mariposa County. And eventually as the states were settled in, people were coming and living in the cities. And there was an association, a negative association, from slavery, from the agricultural nature of most of the slave states, and later on sharecropping when people talk about the great migration in the 20th century. But there's a deep, deep history of cultivating the earth that starts with the African-isms that we brought to the United States. Now what we're looking at in this picture is the first thing that you, this exhibit is down now. And what we do, what we've done is that there's a traveling exhibit version of this exhibit that's in the Roots Center. But this is how people encountered the first thing they encountered at my museum, which is the California African-American Museum. And more images from the museum, those are actually four separate images that are joined together here. And you'll see here in the Roots Center the use of historical photographs, texts, a theme run, there's audio. In the gallery show we had video, we had archaeological objects from several homesteads, highlighting the connection of African-Americans in California to the state's rural, agricultural, and wilderness history, especially in the focuses on 19th and 20th century. This is an image from one of my favorite painters, Jacob Lawrence. And if any of you know his work, if you don't know his work, I encourage you to know his work. He has done a lot of series. He did a series on the Great Migration, he did a series on Harriet Tubman. This is from a series he did in the late 50s called The American Struggle, which starts with the American Revolution. And this panel was a way of portraying the overland movement west. Actually, before the gold were starting really in the 1840s when the definition of the west actually was different. So as far as how the exhibition came about, for several years I've been working on a book for heyday books, and they're very kind to me. They don't ask me, where is that manuscript? And they just, you know, they've been very patient, very generous. Because this history of California's African American past has been so successfully buried that when I was asked to write the book, I thought I knew something. And then I started really researching and traveling around to the collections of local historical societies, for instance, local archives, and finding out things that I didn't know about and most people didn't know about, except for people in the local area who get their finger on the pulse of the history of their area. So I had to keep learning in order to work on the book. So the first volume that I'm working on is an account of California's black 19th century history. I'm doing things like I realized after doing a lot of reading that even the histories that acknowledge, you know, well, there were black people here during the gold rush, or there were black miners, there must have been, there are daguerreotypes of them. Nobody ever talked about how they got here. There's no documentation or narratives or first person versions of their overland journeys, or of the people that came as mariners who worked on ships, or who came as passengers on ships. So I actually spent a good section of the manuscript talking about those travelers. And as I've been working on this book over these years, one of the things that I noticed was that it didn't matter what region of the state I was looking at. It didn't matter if it was Shasta County, anywhere in the far north, didn't matter if it was desert, didn't matter if it was Imperial County, and the Mexican border. In the 19th century and early 20th century, African Americans lived there. They were part of these early communities. And they were wiped out of historical accounts. This didn't just happen in California. It's happened on a larger scale across the country over a long period of time. So in a lot of ways, the work is a work of restoration. And when I realized that, I thought, I had to say something about that. People's picture of early California in rural communities doesn't contain what I'm learning. And that's how the exhibit came about. Looking at people who are homesteaders, farmers, ranchers, and importantly, too, what I found. Because California was a really different state. Its government, its politics, its policies, its practices than it is now during this time. And the people, the African Americans who came and settled in these areas during these periods, when California was just becoming California, brought with them a civic culture of their vigilance about equal rights. So this is a picture of what was politely called Negro bar on maps, but that was not what it was called. I'm going to tell you something that's historically true. There are, as you know, there are place names, geographic place names all across the country that were derogatory in all kinds of ways and against all kinds of people, slurs against all kinds of people. And there were, you can look at old maps and anybody who's done this can attest. And if we're just talking about these cases, you will see thousands and thousands of place names the N-word. Including in California, in fact, part of the reason that we know that there were African American residents in California during the Gold Rush is there were so many place names that white people associated them with that started with the N-word. And there was a scholar who died seven years back whose research was kind of ignored, Joe Louis Moore, whose wife Shirley wrote a really important book about African Americans in the Overland Trail. Joe found at least 75 place names that signified mining camps during the Gold Rush. So there were just generations of maps that had N-word canyon, N-word bar, you know, N-word point, N-word jacks, mountain. And what happened was that during the sixties, when Stuart Udall was, I think, LBJ's interior, Secretary of the Interior, and the Civil Rights Movement was peaking. Civil Rights leaders went to the Secretary of the Interior and said, we can't have this anymore. You got to do something about this. And so, you know, there's a federal agency, I'm actually on the advisory committee in California, to that agency, the California Advisory Committee on Geographic Names. And each state has such an advisory committee, and we deal with name changes, whether they're derogatory or not, and make recommendations to the Bureau of Geographic Names. So out of, you know, capitulation to the Civil Rights Movement, out of embarrassment, map names change. So if you see a place on a map, a modern map, from the last part of the 20th century, that's Negro someplace, that's the reason. Because every time we look at that, you're actually looking at Edward, okay? So this, you know, is just one of the areas, and there's been a lot of controversy that I could tell you about, because this is actually now part of a state park, that I'm working on a partnership with the state parks on interpreting African-American history. So during the gold rush years, African-Americans were part of that huge migration to California. And California offered opportunities, the first one being at least the whole, to gain wealth, digging gold. There were other opportunities to bargain with enslavers over purchasing your freedom. This was a rare occurrence in slave states. In fact, many, there were many people who were hired out, who did earn money to purchase their freedom in southern states. And the people that owned them, their enslavers just said no. That's what happened in the Dred Scott, the famous Dred Scott case. Dred and Harriet Scott and their daughters had lived in a free state. Before Missouri became a slave state, and they went to court saying, you know, we claim our freedom, but they only went to court after their, oh, their enslaver refused the money that they tried to purchase their freedom with. In California, it was a different dynamic because everybody was making money and trying to make money. And it was a wilderness. And you can hide in the mountains. And people, there was a really high incidence of people bargaining and saying, okay, if I, if I bring you a thousand dollars, then I expect, you know, to be man-emitted. And people agreed to that because of the kind of fluidity in the situation in Gold Rush, California. But California also had challenges. The original Constitution of 1849. Now, this is Colton Hall, which is where in Monterey, this picture is taken about 1890. This is where the Constitutional Convention gathered in 1847, 1849, I'm sorry, and came up with the first Constitution. And the original Constitution, California's of 1849, reserved the vote for white men only. And, you know, if you read the clauses, it's very simple to read this Constitution. That's what it says. And I don't know if you're aware of this, but the, you know, when there was the, at the Civil War, the campaigns to gain the vote, the black vote, the black male vote, the issue was framed them as remove the word white. And then, you know, later during this, the campaigns for suffrage for women, it was the same campaign, same goal, remove the word male. And that's how we got to where we are today. So the California Constitution spells out very clearly that the vote, it belongs to white men only. And it says Mexican men who choose US citizenship. Black people and Native people were prohibited from testifying in court in the Constitution. The Constitution prohibited both groups from attending public schools at all. And that's a whole story of how that changed the campaigns, especially that the black community waged the lawsuits that were brought over generations before the law was changed. And first, they were allowed to go to colored schools, and then the law was changed to open all schools. So California at the time of its founding, and until the Civil War, the government until 1863, really, precisely, the government was dominated by what they called SHIV Democrats by pro-slavery whites in the legislature, in the schools, the judiciary. And the response you can see looking in history was in petition campaigns to allow court testimony in black newspapers, and from church pulpits, the conventions of the colored citizens of California. What you're looking at here is a piece of a masthead of the first issue of the elevator newspaper, sorry. The elevator was California's second black newspaper. The Mirror of the Times was the first. It was published in 1857, and the elevator ran from 1865 to 1898, and Philip Alexander Bell was the publisher. That's a whole story as well. And here you're looking at the cover of a published proceedings of the first state convention of colored citizens of California. And the people who, among the African-Americans who came to California during the bold rush, and beyond, were people who were very politically active. There were primarily free people who came from Atlantic states like New York, Massachusetts. There is, for instance, a huge community who came from Bedford, who knew Frederick Douglass personally. He wrote about them in his newspaper. And Pennsylvania and other areas like that, there was another population who were forced to come here by enslavers. And the people who came on their own volition, on their own dime, they brought with them a legacy of activism. They had been leaders in the anti-slavery movement in their home states. They ran vigilance committees, which is how the Underground Railroad operated, giving aid to fugitives. And many of them were very close to what you could consider the national leaders of the anti-slavery movement like Frederick Douglass and others in other states. These were these were people who were personally involved, who were known in the movement. And by 1830, the movement really crystallized. The convention movement came together as a response to white mob violence in Cincinnati. And there were thousands of African-Americans who left for Canada after this violence. I'm sure some of you have heard of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the destruction of the Black neighborhood there. Well, you know, they were sorry to say there were hundreds of such incidents. And they started long before the 20th century. And Cincinnati in 1830 was so shocking, the burning, the looting, the killing, that it mobilized Black leadership in the free states and they formed the color convention movement. And many of the people who became quite well known when they came to California had already been attending their state's convention movements, meetings, or they were sent as delegates to the national conventions. So they would come here. And before you know it, and by 1855, African-American leaders had organized their own convention movement right here in California, was held in Sacramento. The first Black AME church, possibly the first Black church, established in the Western United States, St. Andrew's African Methodist Episcopal Church in Sacramento, it's still around. And that was where the first state convention of colored citizens was held. The proceedings are accessible online. And if you like reading that florid 19th century rhetoric about justice, you can read these some of these speeches online. They're really amazing when you think that these are taking place in our state in 1855. I just want to make a point, a little aside that's related to this, but when I do this research and I see, you know, what the response was to the violence in Cincinnati, we see this every generation in the United States. You know that's how the NAACP was formed in 1909, because of the Springfield riots. White mob violence in Springfield in the country was so tough that Abraham Lincoln's hometown was the location of this bloodshed that it just sparked, you know, people who had been separately doing this work to come together in the National Association for the Advancement of Color People, which still is around and still is necessary. The same thing happened for those of us who were around after King was assassinated in 1968. You know, we keep reacting with horror. So it happens every generation. And just, I think that we have to do a little better than that. All right, so I am going to ask you how we're doing on time and just tell you a couple of stories from the exhibit. So the family that I've chosen, there are several families from all different regions of California who are kind of profiled in a way and described in the exhibit. I'm going to focus right now on the Heinz family. And what you're looking at here is a picture of one of their workmen on one of their 3200 acres into Larry County. This was Toby. I never knew his last name. And these are actually prunes drawing. And when you see the whole picture, this is actually from a wall that was in the gallery at the museum. When you see the whole picture, it looks like miles and miles of prunes drawing. And then on the right is a postcard that Lucinda, Mrs. Lucy Heinz, had a collection in an archive that we borrowed this from, of postcards from one of her friends. And they all had these kind of farm and agricultural subject matter. And I just thought this was beautiful, this horse postcard. So Wiley Heinz was 15 years old when he arrived in California in 1851. And he came across from Arkansas with two white boys he had grown up with. And they were all, they all had the last name Heinz. I won't get into the details of that, but it's a very common American story. They made it to Tulare County. And he started out as a young man making his living as a vaquero, a ranch hand, and people who noticed him always talked about a kind of dignity he had. And he earned a lot of respect for the way he carried himself, his honesty, his level-headedness, how hard he worked. And all the while he was working, saving money and acquiring property. Now on the left is a picture of Wiley Heinz the year before he died and or close to the end of his life. In the middle is a much earlier picture of Lucy, the kidding Heinz, his wife. And then on the right is Wiley Heinz in a much earlier picture as well, driving a horse and carriage. And these, I have looked and looked at that image and I think those are pumpkins. And when, you know, I've looked into the collection, the images in this collection, and there's a picture of a farm hand carving a watermelon that's about four feet long. I am not exaggerating. I mean, they were really doing something on their on their farm. So in 1873, Wiley Heinz went back to Arkansas to marry his young sweetheart Lucinda McKinney. They moved back to Tulare County to the home that Wiley had established. They had eight children, seven survived through adulthood. And Heinz in the end amassed 3,200 acres of land, including farmland in Farmerville and city lots in Visalia. His ranch was one of the most successful in Tulare County. He grew weed and he grew pumpkins, watermelons, Alberta peaches. He was also a cattleman and raised other livestock. And Visalia had a segregated all-white school and Wiley ended up being involved in a big case in California that I'll mention in a minute, that took, that went to the California Supreme Court when the teacher at the white school would not allow black children to come to the school. But in the meantime, Wiley actually hired a teacher, an accredited teacher, Daniel Scott, a black teacher and his children received their own tutoring. And then Scott later went on, and there's a whole story about that too, but he opened a school for African American and Mexican children in the area. Lucy and Wiley were steadfast members of the Methodist Church in Exeter. Wiley was a respected citizen and he, people knew him as a man who loaned money to anyone who worked hard and wanted to better themselves. This is also, they also owned this home in Oakland that you can see on the top and that's actually, this was his retirement home. Lucy and their younger children lived in Oakland after a while and one of their daughters, Pearl, one that I talk about in a minute, she wrote that she remembered when the Wells Fargo stagecoach used to come to Oakland and bring melons and all kinds of good stuff from the from the ranch. But he finally retired and moved to this home and that's Wiley and Lucy on the porch. And then the house still exists. The bottom is a picture of it in 2022 on 34th Street in Oakland. One of the things about them and about the people and the families and these farmers and ranchers and homesteaders that we look at in the exhibition is how much they contributed to the development of the state. And not only were they acquiring and cultivating property, cultivating the land, but they were gambling on the future of California. They were investing in the state. So out of all of their children, this is Pearl up at the top, Pearl Hines and her portrait and her sweetheart Frederick and Roberts down at the bottom, both around 1900. Pearl, her parents could afford to send her to Oberlin College. She trained as a concert pianist and performed as well. And she started dating Frederick and Roberts of Los Angeles. Frederick's family owned a mortuary and he published a newspaper The New Age. Frederick's mother Ellen Wales Hemmings was the daughter of Madison Hemmings and Mary Hughes McCoy and the granddaughter of Sally Hemmings and President Thomas Jefferson. So this family has still has descendants in the state. That's another thing actually quite a few of the people when you look at the exhibit, the families have descendants today. And I bet you didn't know that there was a branch of the Hemmings Jefferson family in California. There is, there still is. And you know, the two of them were part of kind of, you know, she was at Oakland in that house that we saw, although she traveled a lot as a performer. And he was in LA, but they were part of a social set. They had friends across the state. And, you know, this is actually something that exists today. That, you know, if you if you belong to certain clubs or certain alumni groups or certain families that you're going to be connected with people, that's true for everybody. And it's true for these families as well. And there's the same two. Now Pearl, that's a 1970s portrait of Pearl and a 1950 portrait of Frederick. They got married. And Frederick, part of the reason that the Wiley Heinz, Lucy Heinz, they only lives on and is important to know about is not only in their own right, but Frederick Roberts was elected the first African American in the California state legislature. He was an assemblyman. He was actually involved in some important legislation, civil rights legislation in the state capital in the 1920s. He died not long after this portrait in 1952, but Pearl lived quite a while. And I'm just going to move quickly some of the other families that we mentioned in the exhibit and you can find out more about them when you go take a look. The coffee family, another family that has so many descendants. Such a dramatic story. Alvin Coffee was brought from Missouri with a party of people that actually were the founders of the Society of California Pioneers. And he was the first black member of that society. And his reminiscences, that's the Society of California Pioneers for a while, their historical committee used to record the reminiscences of the pioneers. And his was included. So it's a remarkable first hand recollection of coming overland. And he came with, he was enslaved. He bargained with his enslaver. He earned the money to buy his van mission and his enslaver reneged on the deal. This happened all the time. I have read so many examples of that happening where people had to earn that money over and over again. He eventually earned the money to buy himself and his family. He ended up crossing, doing the overland journey three times. And finally, the last time his family was free, they moved to what was then Shasta County, now it's Tehama, where they live in Red Bluff, is Tehama County. When they, during this time, there was no Tehama County. And he had a turkey farm. Several hundred acres, I can't remember. He and Mahala ran a school for African American and Native children in their home. And then on the bottom, there's more about this in the exhibit as well. Edwin Weisinger, who took his case when his son Arthur was not allowed to go to the public school in Visalia all the way to the California Supreme Court and won the case in 1890. And the case which had made prohibiting Black children, prohibiting anybody from going to school, illegal. And that case was actually cited by the team of lawyers led by Thurgood Marshall when they argued Brown versus the Board of Education in 1954. So this is another reason why local history, there's no such thing as local history. Just moving on and I'm about to wrap up, one of the aspects of the exhibit as well is we look at independent settlements set up by African Americans for a whole range of reasons. There's Allensworth, that's the schoolhouse. Allensworth was a civic act, it was a civic experiment very clearly set up to establish, to prove the people who lived there were worthy of citizenship that was founded in 1908, about 40 miles north of Bakersfield. It's a state historic part now. So that's a restored building. And then there's the two kind of cat and corner issue images of Lincoln Heights up in Shasta County. Sadly a lot of Lincoln Heights was destroyed during the wildfires up in Shasta County a few years ago. And then William Payne told the story, he was the educator in Allensworth but he left and went to Alcintro, which is kind of a black, a black on-cape play in Alcintro and played a really, really important role as an educator. So I'm going to end there but what we want to do is ask Linda Jack to come up and talk about some of the local examples of homesteaders and community leaders in Nevada County during this historical period and then we'll open it up. Okay. Thank you very much Susan. I think one of the things that's so interesting about this topic is it covers everything. I mean you think you're looking at a small thing and pretty soon you're not. So what we tried to do for the local exhibit was to have into the themes of the exhibit but tell some local stories and I will do this briefly because you can see them at more length of the exhibit. So what struck me from the beginning was that Nevada County although we know our level of sophistication here there and yonder in our community it is still largely an agricultural and land-based place to live and we all appreciate that through the Flora Juana, the Yuba River and all the other things that we love about it. So I sort of started with that point and one of the things I realized quickly is that people working people in the 19th century they didn't have a job you know they couldn't just be well if you were a lawyer or a doctor perhaps you could but if you were an average person with a family you did whatever you had to do to take care of your families. So we have a mix of three stories we told in the exhibit what I think today we might call an urban farm because now this farm is in downtown Grass Valley but this was the Savelle family their little ranch farm was on Pleasant Street which is all now apartments and condos and it went back up at what we now call Peabody Creek right up against Condon Park and this was they raised George Savelle raised prize-winning poultry they were always winning awards of some kind of small livestock he had a famous walnut tree that produced 80 pounds of walnut per season he had some purses that he round out in Lundberg Park but he also worked for the city he was a head hauled trash he did work around you know for the city all over town so that was the first family the second family that we looked at were the Goudere family they were Nevada City and they had a big ranch out on cement Hill Road both George Savelle and Henry Goudere had filed for land planes so they were homesteaders later in the homesteading process that was a very large piece of property and he grew rye he grew timber for wood he had animals we have his farm inventory so we know what he did but he also must have been quite the entrepreneur because they had four pieces of property in downtown Nevada City rye cottage and pine behind the courthouse and one of the qualities about the two families uh which i think was also common at the time is they were blended families people did lose their spouses through one way or another and both Savelle's and the Goudere's had children from different uh families that came together the third person that we looked at was a very different approach because of that i think refers to California or combata county's natural resources was a man named Albert Johnson he was in Truckee he had been enslaved as had both George Savelle and Henry Goudere and when he got to Truckee the Donner Lake area he fell along and decided this would be his place and i think today we would call Albert Johnson a naturalist um he knew all the fishing streams he knew uh he took people on hiking and hiking up them but trips into the back country he had a saloon and hotel uh at Donner Lake um and then he had a set of cabins that he rented out to hunting and fishing parties and he um seemed to be one of the most well-loved most respected people in the whole region and he once decided as seeing a bunch of quail with that stuck on the frozen lake and went out there and tried to rescue all the quail he could to get them off the lake before they all froze to death so um his story was more one of somebody in on the land but who built this um respectful network of people when he became very ill he was stranded in the snow he lived pretty far off uh he came to the Nevada county hospital here and about a city and that's where he passed away um so all of these people um have these qualities that was that were common to other uh bold rush era people of all races mixed families having to do whatever it took to take care of your family um having built respect in your community um and making a life um earlier than many other black people in America because they didn't have to wait for the other civil war to have their freedom now we don't know about Albert Johnson but both George Seville and Henry Baudier were very active in uh civil rights movement they were among the first men to vote uh after the uh 15th of November passed and they registered way ahead of time or they self-identified well ahead of time so they could be in that initial cadre to vote um so their stories um uh sort of cover all these bases and their wives and family had very independent lives as well uh in the Lodera family they were also very musical uh L6 of their children played and performed and they toured all over further California to perform their music um and perhaps the most famous descendant of the Seville family is a woman who ended up marrying uh also Rachel Rachel Seville Rachel Eisen was her was her family name and she married a guiding Jackie Robinson and um had an amazing life herself she was a nurse taught nursing uh psychiatric a pediatric and psychiatric nursing both I believe she worked independently taught nursing and nursing school and when her husband passed away she uh founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation around it and built housing for um underprivileged people so she she had an exemplary pardon she's still alive she's a hundred yeah the last I knew she was 104 this summer but she lives back in Connecticut um and I have through uh Susan's kind races I have been in contact with one of the family members so um their stories are all filled with more detail in the exhibit but they just kind of I think exemplify this mix of people who came here and made of their own talents and their own experience built lives to sustain large families so thank you do you want to hear should we just take questions any questions for Susan or any of them no question well I'm sort of interested in this photograph right here could you tell us what that's all about um sure um that I don't know who the people are um but that is on why the property so that's all I know and I keep you know I looked at this a zillion times that's um trying to see if I recognize anybody um the woman who's third from the left on the bottom looks really familiar and I just haven't done the work to track it down but that's it's about 1908 and it's a gathering on Wiley Hines property yes go ahead do you ever bring forward or explore in the life of James Becker yeah um we you know my book is he's sort of an introduction to my book because I'm starting with the gold rush in statehood um but you know if you're up in Yuba county like batworth is everywhere there's there there's him but up Yuba too I mean he's remembered you have to go up there to find anybody who really knows anything about him anymore yeah but um you know I'll tell you he's sort of tough to research because you know there's a famous um autobiography so-called you know as told to biography that was published during his lifetime and it's it's so fully you should know it's hard to tell if there's any facts and people have tried to track things down and the guy that and you know that was a formal literature back then that kind of pulpy mountain man you know um uh story for for masses of people so it's there's not there's really as far as documenting his life it's kind of tough yes you just touched on slave holders in California and I'm wondering if Linda would tell the story of the Kentucky mine what happened there sorry Kentucky Ridge Mine uh yeah the Kentucky Ridge Mine between Newtown and Rapid Ready um and it was established by uh a man named William F. English who was uh South Carolina uh Florida South Carolina but uh transported himself down to territorial Florida quite early um and made a stop in Georgia on the way here so he's often referred to as a Georgian but he really wasn't but uh he brought about between 30 and 40 enslaved people around the horn um on a steamship he commissioned um but he died uh in a self-infected gun accident dismounting from his mule about 18 months after he arrived so the people who were enslaved by him although technically free in a free state of California they practically were not um were able to essentially walk away from their slave room now there was a rumor that his uncle who was done on the site tried to extort um those people to buy their freedom um but I haven't found documentation for that so by the way there were at least a dozen uh southerners who brought enslaved people to Nevada County so he was just one of them but he by by certainly brought the most people mostly it was one or two people to work the mine or domestic servants um some pretty famous people um that we know and still study of Nevada County history uh different people living in slaves uh just had a comment you mentioned uh she mentioned um secretary Udall I'm from Washington D. C. uh originally and my grandfather was um his chauffeur for many years and his the stories that I heard about the work that he did Udall for civil rights and equality are pretty amazing including making the formerly named Washington Redskins uh integrate their team because they were playing in a in a you know a national uh facility formerly D. C. stadium so thank you ladies