Enter a name, company, place or keywords to search across this item. Then click "Search" (or hit Enter).

Collection: Videos > Speaker Nights

Video: 2024-06-20 - The History of the South Yuba Canal with Dom Lindars

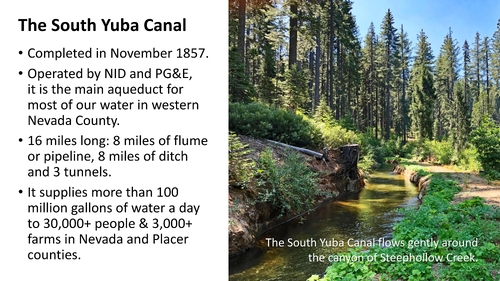

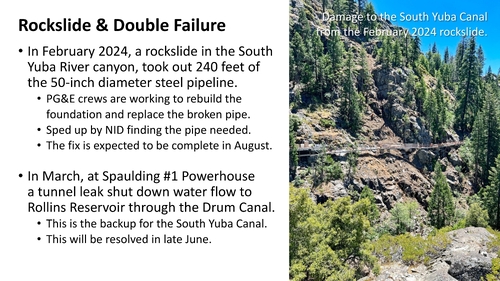

Today, much of the water for western Nevada County is transported from the high country along the South Yuba Canal. This became particularly apparent in February 2024, when a rockside just below Lake Spaulding, damaged 240 feet of the canal’s 50-inch diameter steel pipe. Combined with a badly timed leak inside a tunnel at the Spaulding powerhouse, this stopped the precious flow to Nevada City and Grass Valley of more than 100 million gallons of water a day.

This talk will take a look at the origins of the canal, the fight over how it came to be built and the mammoth engineering that was involved.

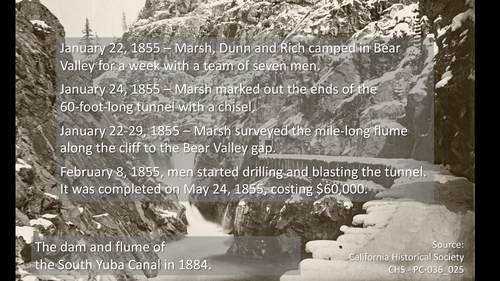

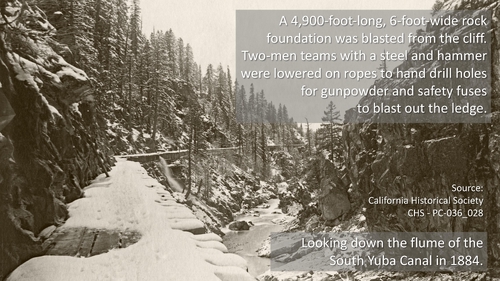

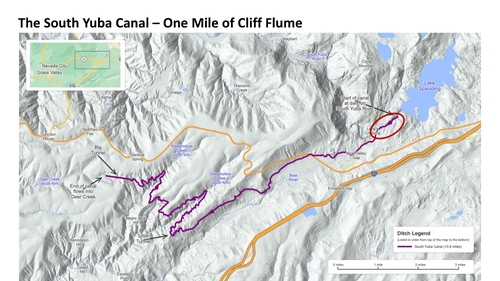

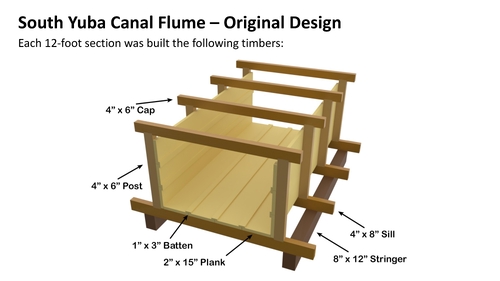

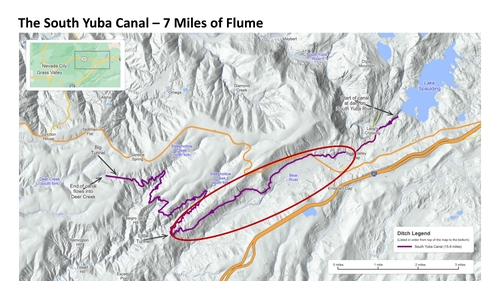

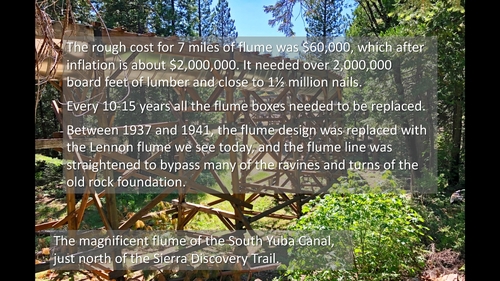

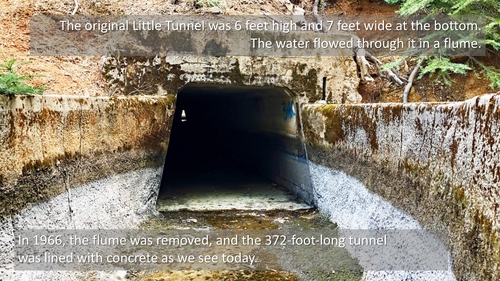

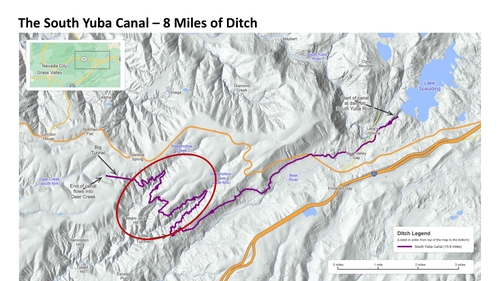

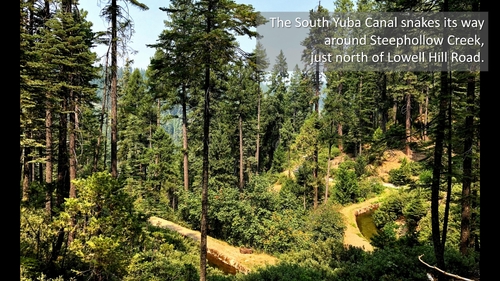

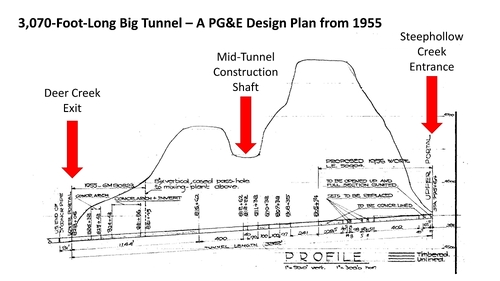

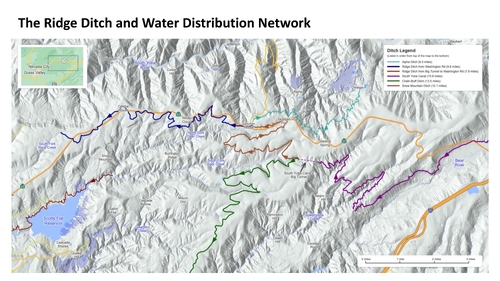

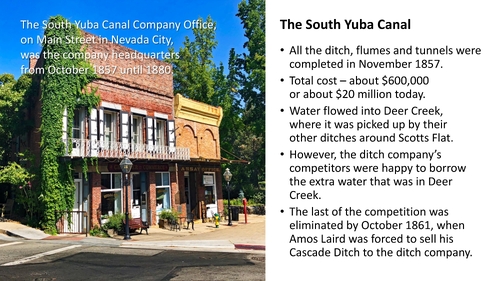

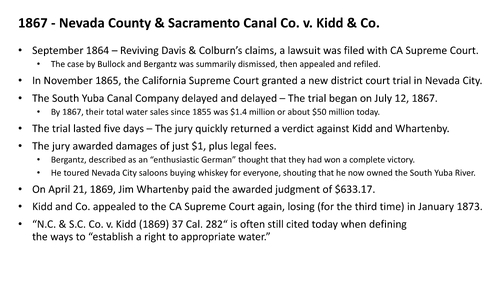

At the time the South Yuba Canal was built in the late 1850s, its 2½-year construction was heralded as the “most extensive and costly enterprise” in California. Some people thought it was a financial scam run by rogues. You’ll hear how the entire concept, the water rights, its planned route and even its name was stolen from the original founders. There followed a battle of words and a battle of wills, a near-violent confrontation with 60 gold miners, claims of trespassing and counter lawsuits, all spanning nearly 20 years. Building the canal involved blasting out a mile of vertical cliff ledge, building 7 miles of flume, digging 8 miles of ditch and blasting a 3,000-foot tunnel. This was all while the ruthless and greedy South Yuba Canal Company worked out how to crush its rivals to establish a monopoly over all the water for gold mining in Nevada City and Grass Valley.

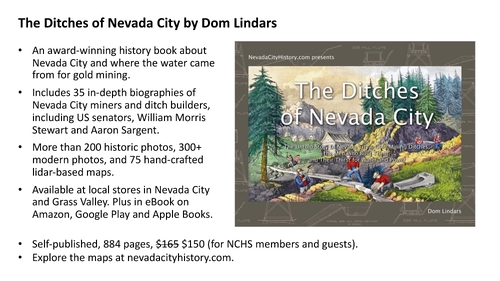

This story is taken from the award winning book, The Ditches of Nevada City, whose unique format blends beautiful archival images with more than 35 in-depth biographies of key figures in Nevada City. This 884 page hardcover book includes over 600 full-color illustrations, including 200 historic photographs and 75 hand-crafted maps based on modern lidar technology that reveal the locations of the old mining ditches, flumes, mines and tunnels. For more information, please visit the website.

Amazon Reviews

“Local history in full color, author Dom Lindars has captured Nevada County’s volatile past, in our ditches, in our gold-fever and other influences. Is it a reference book? A history book? Or a fascinating encyclopedia of challenging times long gone? Each time I turn a page, I change my mind – and I learn something new. It’s attractive enough to be a “coffee-table book,” but its content runs deep. Meticulously researched, it’s full of eye-opening, sometimes quirky facts. It’s a book that deserves pride of place on any history buff’s bookshelf.” – Local GV Author

“This book is absolutely essential to anyone interested in the history of Nevada City, California. It is physically a massive tome; with almost 900 pages full of thick, high-quality glossy paper. The history of the ditches is presented in a very readable and engaging format, supplemented with an enormous quantity of full-color photographs. Dom Lindars has truly created a masterpiece for posterity with this impeccably researched book that is both engaging and entertaining. Mr. Lindars is clearly passionate about history, engineering, accuracy of facts, and a true love for this locale. Although it isn’t physical gold, Dom Lindars has created this absolute treasure with words.” – Nevada County resident.

This talk will take a look at the origins of the canal, the fight over how it came to be built and the mammoth engineering that was involved.

At the time the South Yuba Canal was built in the late 1850s, its 2½-year construction was heralded as the “most extensive and costly enterprise” in California. Some people thought it was a financial scam run by rogues. You’ll hear how the entire concept, the water rights, its planned route and even its name was stolen from the original founders. There followed a battle of words and a battle of wills, a near-violent confrontation with 60 gold miners, claims of trespassing and counter lawsuits, all spanning nearly 20 years. Building the canal involved blasting out a mile of vertical cliff ledge, building 7 miles of flume, digging 8 miles of ditch and blasting a 3,000-foot tunnel. This was all while the ruthless and greedy South Yuba Canal Company worked out how to crush its rivals to establish a monopoly over all the water for gold mining in Nevada City and Grass Valley.

This story is taken from the award winning book, The Ditches of Nevada City, whose unique format blends beautiful archival images with more than 35 in-depth biographies of key figures in Nevada City. This 884 page hardcover book includes over 600 full-color illustrations, including 200 historic photographs and 75 hand-crafted maps based on modern lidar technology that reveal the locations of the old mining ditches, flumes, mines and tunnels. For more information, please visit the website.

Amazon Reviews

“Local history in full color, author Dom Lindars has captured Nevada County’s volatile past, in our ditches, in our gold-fever and other influences. Is it a reference book? A history book? Or a fascinating encyclopedia of challenging times long gone? Each time I turn a page, I change my mind – and I learn something new. It’s attractive enough to be a “coffee-table book,” but its content runs deep. Meticulously researched, it’s full of eye-opening, sometimes quirky facts. It’s a book that deserves pride of place on any history buff’s bookshelf.” – Local GV Author

“This book is absolutely essential to anyone interested in the history of Nevada City, California. It is physically a massive tome; with almost 900 pages full of thick, high-quality glossy paper. The history of the ditches is presented in a very readable and engaging format, supplemented with an enormous quantity of full-color photographs. Dom Lindars has truly created a masterpiece for posterity with this impeccably researched book that is both engaging and entertaining. Mr. Lindars is clearly passionate about history, engineering, accuracy of facts, and a true love for this locale. Although it isn’t physical gold, Dom Lindars has created this absolute treasure with words.” – Nevada County resident.

Author: Dom Lindars

Published: 2024-06-20

Original Held At:

Published: 2024-06-20

Original Held At:

Full Transcript of the Video:

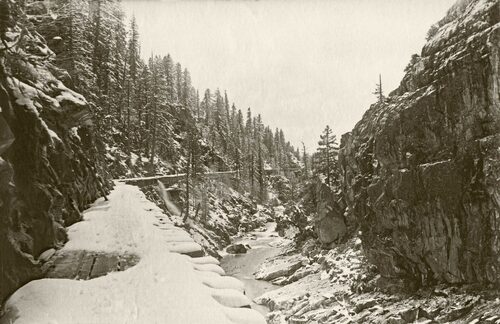

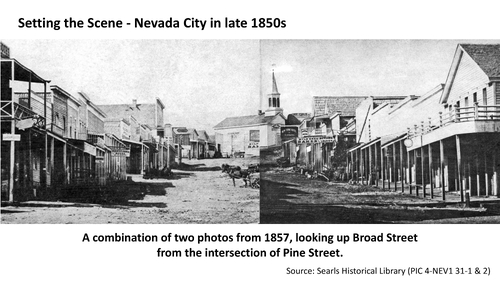

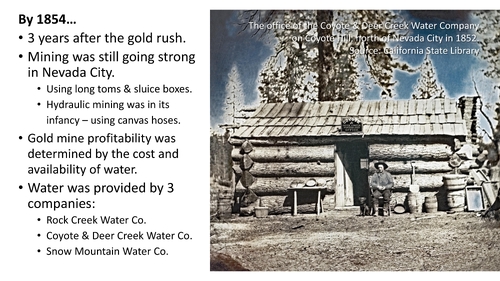

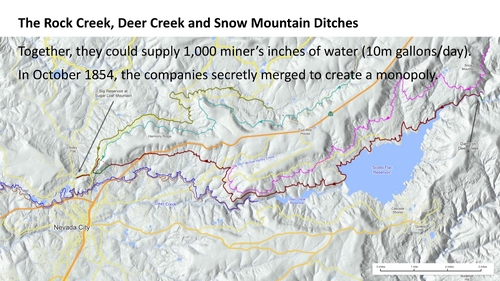

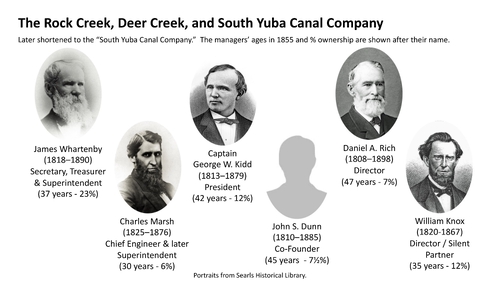

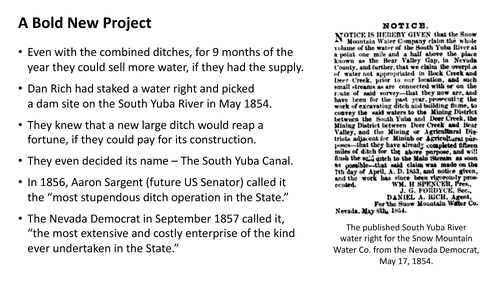

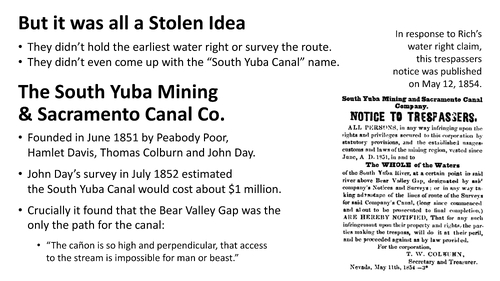

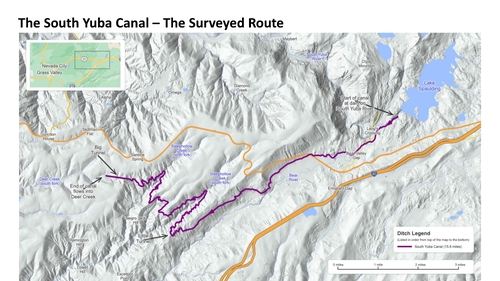

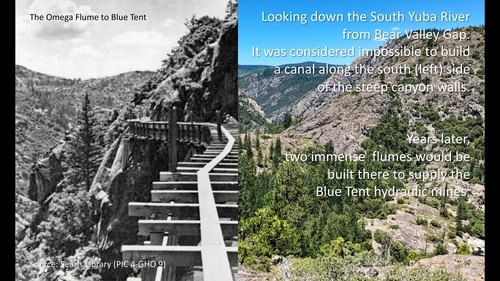

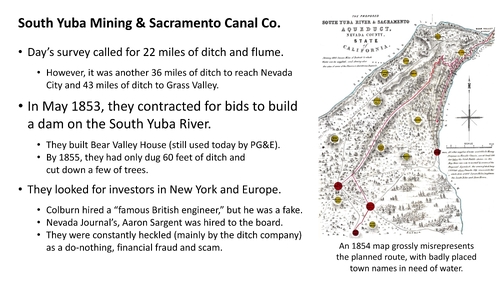

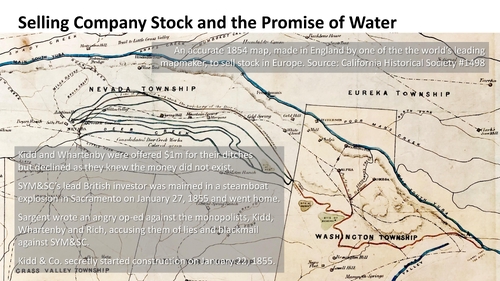

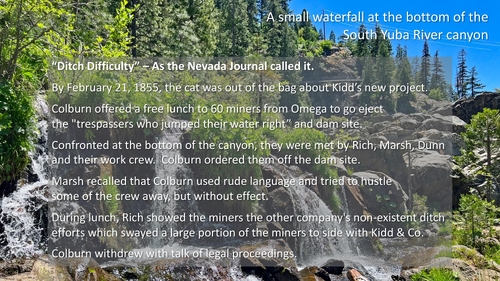

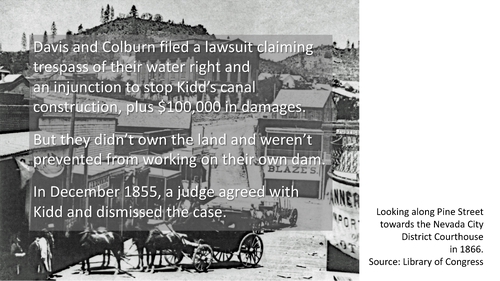

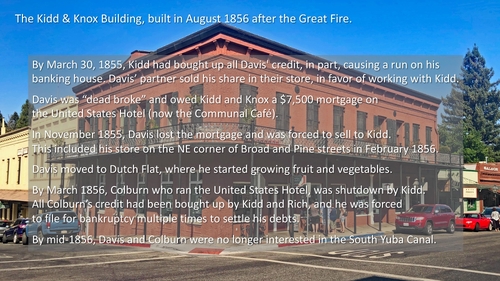

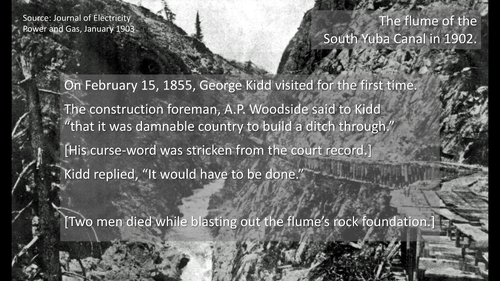

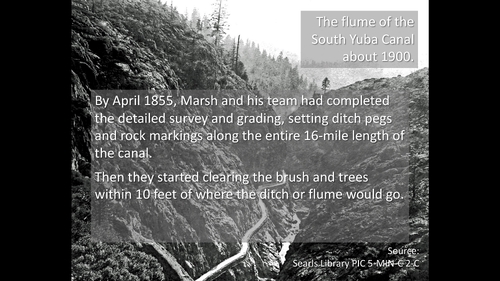

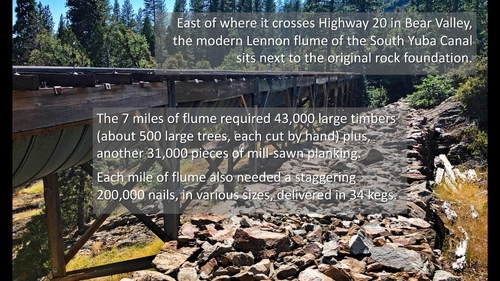

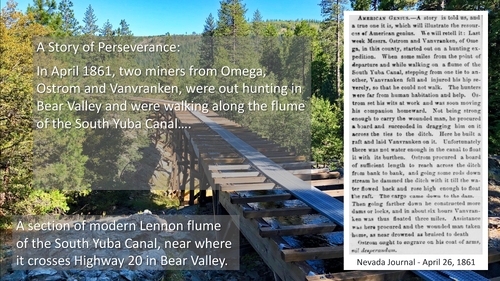

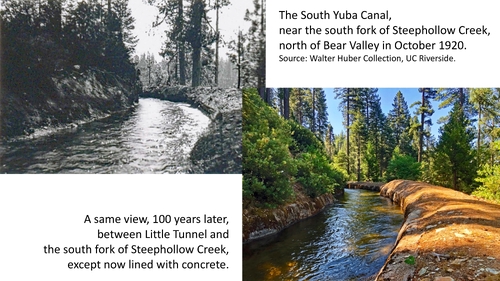

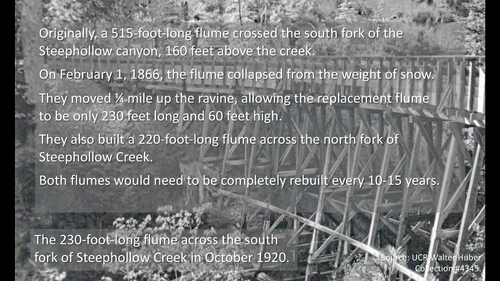

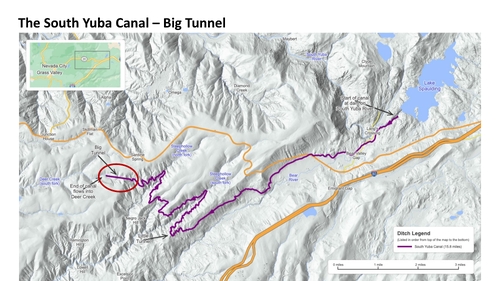

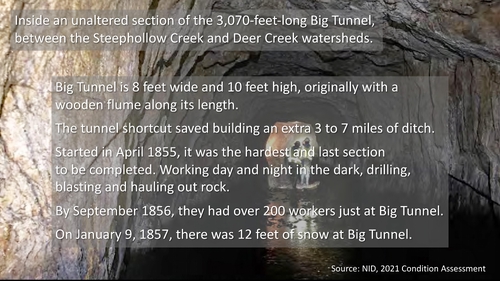

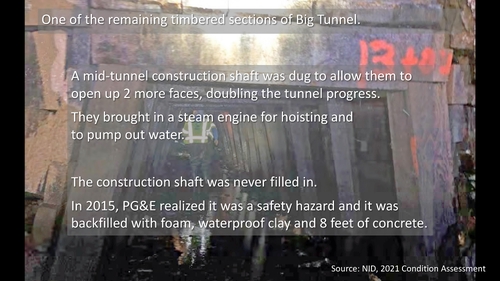

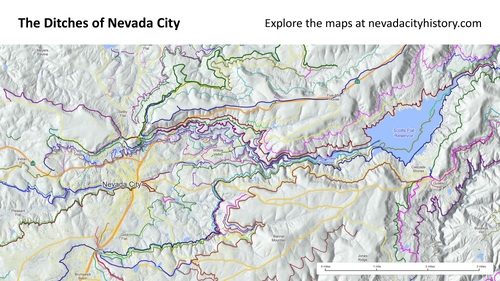

Without any further ado, Chris has got to introduce our speaker for the evening. If he can't hear me, just let me know and I'll speak a little bit louder. [laughter] I am so happy to be able to introduce this evening Don Lenders, who has been an invaluable member to the Nevada County Historical Society. His generous talents and his abilities have really been able to enhance the society in ways that we never imagined prior to him being a part of what we do. In addition to being so incredibly talented and gifted with how he's been able to enhance the society, he's also an amazing author. His meticulously researched "Ditches of Nevada County" is a phenomenal book and has recently been awarded with the Will Rogers Medallion Award in the category of Western Photographic Essays. [applause] So, ladies and gentlemen, Don Lenders. [applause] Wow. Thank you very much, Chris. And thank you all for coming. It's an honor to speak to you so many people. It's just, yeah, I think you know that I have a passion for some of these things. How's the sound level doing? Good? Okay. Oh, yeah, actually, Desmond's going to turn some lights off. Are you ready? Yeah, that's fine. He's not going to throw us into the dark, hopefully. So, thank you so much for coming. How's that? Is that better? Okay, that's perfect. That's great. Thank you. So, when Dan was looking for topics for Speaker Night for 2024, I was just thinking of something that I could put together without having to do three more years of research. And this topic came up. Little did I know that it would suddenly be rather topical for what we've got going on. So, let's actually get into some of that. I think that might be recruiting Dakota to do some slides. So, the South Yuba Canal, it was built in 18 years, finished in 1857, and still today is the primary artery for water providing us here in Nevada County. A hundred million gallons a day. Just what could it be? And I say supplies. Huh, it doesn't. It's not right now. It's been off. So, what happened? So, back in February, there was a rock slide. And you can see here part of where the rocks had come down. So, the top, I'll get into this, part of the South Yuba Canal is carried in a 50-inch diameter pipe. And a rock slide took out 250 feet of that. And so, that would have been okay. So, one thing you need to understand about who to blame for some of these things, so we always have to blame people, right? So, NID did indeed buy the South Yuba Canal for $1. And it got, and the South Yuba Canal now is run primarily by NID, except for, you guessed it, the top mile. Where did the rock slide happen? Yeah, that's right, the top mile. So, it's PG&E's responsibility for the rocks. They were in responsibility for the rocks. Can we blame them for the rocks? I blame them for the trees when they fall on our power lines. So, the rock slide, it definitely took out the pipeline. That wasn't necessarily their fault. They're fixing it. But at the same time, there was a problem at the Spalding powerhouse where there was a leak. And the backup that would have provided water to bypass through the drawing canal down into the South Yuba Canal, that also broke them as well, which means we're getting no water from leaks falling at all right now. And so, hopefully that's going to be fixed in June. But with this, you know, you can see, this is actually kind of important about where we get our water from. And the fact that we've got our water here in the county since 1857 because of this engineering model. So, let's get into a little bit more of the story. So, going to take you back to the 1850s. This is what Broad Street looked like in 1857. It's two photos. So, you can see there's a horse and wagon, but the wagon is kind of, wasn't in the other photo. So, the church is kind of smooshed together. But you get an idea of that. This is standing at Pine Street, right? So, if you're standing in front of the chocolate shop, in front of the communal cafe, looking up the street, that basically looking up from there. So, where were we? So, 1854. That's where we're going to start our story. Three years after the gold rush. And yet, most of the rest of California, the gold miners had gone home. They had moved on. Actually, a lot of them went to go live in Napa and Sonoma because they like the weather. Partly because they were broke and they didn't have any money to go home. So, in the right here though, the gold rush continued. And in fact, we'd been mining gold here and we carried on gold mining gold here until 1957. Another 100 years. And that's when we finally started, stopped bringing gold out of the ground. And that's just because there was so much of it here. So, the gold rush hadn't slowed down here at all. And at the time, they were still using really primitive tools. Long tongs, sluice boxes, just very simple. So, hydraulic mining that we all know about was still in its infancy. It was only a year old in 1854. And so, they were still using low pressure. . . they were just using fire hoses, essentially. That's the way you can think about it. Low pressure fire hoses. So, it was more just like washing stuff down rather than blasting it out of the way. So, the key thing here was that if you wanted to make money as a gold miner, you needed water. If you were panning for gold in your sluice box, even as you got going with the mining hoses. And so, the key factor, I would say, throughout the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s, the key determining factor about whether your mining plan was going to make any money was the proximity, availability, and cost of water. So, then it kind of gets important about where the water came from. So, there were three water companies. The Rock Creek Water Company, the Coyote and Deer Creek Water Company, and the Snow Mountain Water Company. I'm just going to point this at the point of view of the code that's going to work better. So, the laser point is going to work better. So, here are the ditches that provided the water for those three companies. So, the, oh, you know, it's the battery. That's easy. You can put that down. So, the Coyote and Deer Creek ditches, the ones close to Deer Creek there, and then above that is the Snow Mountain ditch that still flows today. And then up at the top is the Rock Creek ditches. And so, together, these provided about a thousand minus inches of water, which is just ten million gallons a day. So, this was quite a lot of water, and yet at the time, they already had some plans moving forward. In case the managers of the difference, the owners of the different water companies secretly got together and decided to merge to create a monopoly. And part of this was the beginnings of where we get into our story. So, this is the, these fellows here represent two-thirds of the stock of the company that they formed, which was the Rock Creek, Deer Creek, and South Yuba Canal Company. Now, isn't it interesting? So, you're combining three companies, the Rock Creek Water Company, the Coyote and Deer Creek Water Company, and the Snow Mountain Water Company. You'd have thought you'd have had names coming in from each, but actually, Dan Rich, the top right, he specifically said, "No, I don't want Snow Mountain. It's my company, but I don't want Snow Mountain. " We should call it the South Yuba Canal Company. And the other directors were like, "Well, why? We're not going to get any water from South Yuba Canal. It's miles away. " But he was really in systems, and that's what started. But you can see these fellows, they're in the youngest, Charles Marsh, the former county surveyor, the youngster, just 30 years old, the rest of them sort of in their mid-30s to 40s. These essentially owned all of the water coming into town. So, with the merged company, they got together the idea that, "Okay, we're actually going to start a whole new project. " And the reason for this was that for nine months of the year, essentially when it wasn't raining, they never had enough water to actually satisfy what they could sell. The miners just wanted more and more water. And so, for nine months of the year, if they had more, they could sell twice as much, three times as much, four times as much. And so, they realized they needed to bring in something beyond Deer Creek, beyond Rock Creek. And so, hence, the idea of, "Well, how about water from the South Yuba?" They even decided on a name, as Danrich New, the South Yuba Canal. So, at the time, so you may have heard of a fellow called Aaron Sargent. During most of this story, he's the editor of the Nevada Journal. But obviously, later he became a lawyer, and later on he became a congressman for our district here. And later on then, still, he became a U. S. Senator, United States Senator for California. And he said, in 1856, he called the South Yuba Canal the most stupendous ditch operation in the state. And it was true. This was the attention of the largest engineering project that anybody had ever considered. So, for the failures here, it wasn't their idea. They stole the idea of the whole thing. They didn't have the original or first water right on South Yuba, if somebody else had it. They didn't want to survey the path for it, about where it would go. And they didn't even carve out the name. It's something a little suspicious here. So, the South Yuba Mining and Sacramento Canal Company. It's a mouthful, right? So, that was actually founded in June of 1851 by some Nevada City businessmen, one of whom, Hannah Davis, was actually the first mayor of Nevada City. He wasn't the first official mayor. That was Moses Hoyt. Hannah Davis got elected mayor, and then they realized that the papers that they drew up for the city actually hadn't been validated in some way, and they hadn't been filed correctly and certified by the state of California. And so, the first mayoral election was canceled in his focus. So, he was nearly mayor, but not this one. John Day, so he was from Grass Valley. The rest of these fellows are all nearly born from the grass. John Day was a surveyor and lived in Grass Valley, and actually later on became the county surveyor as well. So, Day went up to the South Yuba in July of 1852 and surveyed and tried to work out how to actually bring water from the South Yuba River watershed over into the Deer Creek or Wolf Creek or Bear Valley watershed. And he estimated, I mean, they founded this company with one sole purpose, to build the South Yuba Canal. That's just not going to be under any illusion about that. So, he estimated that the cost will be about a million dollars. So, for inflation, rough math here you can times by about 30, 33. So, you know, about 30, 35 million dollars for the construction. So, a chunk of change. But most critically is that Day found that the only way you could bring water in anything like a reasonable fashion was through one spot called the Bear Valley Gap. Okay, so how many of you have been up to Lake Bowman or up Lake Bowman Road? Okay, everybody knows where Lake Bowman Road is right? Okay. So, as you drive up Lake Bowman and you come over the crest of the hill, you actually cross Bear River and you come over the crest of the hill and then suddenly before you is the South Yuba Canal. That is the Bear Valley Gap. And in fact, they built a house there. It's a Bear Valley house. It's just right there at the corner. And it's not a coincidence that that is also the same point where you happen to have driven over, yes, that's right, the South Yuba Canal. Because that's where it went through. But it worked out that was the only place you could actually engineer it through. Because as he quoted in the survey, the canyon is so high and perpendicular that access to the stream is impossible for man or beast. It's my sir. So, nice old words. Okay, so we're going to take a look. So, the map here. Hang on. I've got another. There you go. I found another place. Okay, so Lake Spalding. Bear Valley Gap is just here. Bear Valley coming down here. This is the top of Deer Creek. So, just further to the left there is Scotts Flat. So, what we're talking about here, so from here, we're talking about this is the South Yuba Canyon. And obviously without Lake Spalding being there, South Yuba goes up here. This is Jordan Creek. So, this is the survey route. So, this is exactly the route that John Day surveyed to go along down Bear Valley across Steep Hollow Creek and over into the Deer Creek Watershed. So, while they were talking about the canyon with the high and perpendicular cliffs, oh yeah, this is the view from Bear Valley Gap. So, this is looking west down the South Yuba River. So, the South Yuba River sort of comes down through here. The point was, we're not going to be building a ditch along here. It's a little tricky. And yet, ironically, later on, the ditch builders actually built two different ditches and flumes that went straight along here, all the way around here. The winds blew tent for the really large hydraulic mines. So, and here's actually a picture of this, the Omega Flu. So, this is looking in the opposite direction. So, the earlier photo was taken up there. So, this is, you can see the cliff here and the flume. So, this was built in, I think, the 1870s, 1880s. And actually, this was, got rebuilt a few times. This was working until about 1920. They even built a small little railroad on top of this to actually build the construction of it. Absolutely crazy. Hey, I digress. So, the South Yuba Mining and Canal Company. So, they worked out, okay, it's going to cost a million dollars. It's 22 miles a ditch, all right. But this was a sort of a fancy, fictitious map. So, this map was actually printed in England to sell stock for the company to foreigners. It was all, Europe was just, particularly Britain, was fascinated with buying money in American companies. And it was difficult to tell sometimes which ones were, what should we say, bonafide companies and which ones weren't, being nice about it. So, this map is really strange. So, you can see at the top here, those are the crinkly bits. This is actually the, how the problem matters. And then magically, from here, oh, the water is suddenly now going to travel down here, magically 40 miles without any further effort. Okay, all right. Oh, and the little dots are weirdly marked towns that need water. And some of the towns are kind of made up. So, the maps are a little suspicious here. But they did do some work. As I said, they actually built Bear Valley House. So, as you're going over Bear Valley Gap at the top of Beyford, Bowman Lake Road, you'll see there's a PG&E building over on the right. And that's actually still used by PG&E contractors today for housing and local things. And so, that is actually the only remnant of the south here, the mining and Sacramento Canal Company. It's the fact that Bear Valley House is still there. So, they look for investors. One of the founders, Thomas Coburn, he even hired a famous British engineer. He's like, "Oh, he's going to come in. He's going to take charge of it all, and it's all going to be wonderful. " Yeah, made up resume, completely fake. So, they hired Aaron Sargent to be on the board for Good PR. But, you know, it didn't really matter. The part of the problem, everybody thought it was a scam. And part of the reason is that Coburn and his partner, William Rickby, who was, by the way, a convicted felon, they had been, so they were the directors of the Bunker Hill Mine that had defrauded investors out of $80,000 the year before. So, "Oh, would you like to invest in my company?" "Oh, don't worry, the bad guy ran the Bunker Hill thing last year. That was absolutely absolutely different thing. This one's a good one, right?" "Yeah, okay. You get the idea, Robert. " "Yeah?" "About a million dollars. " Okay, so the interesting thing is they actually got one of the world's leading Victorian mapmakers, the guy that created this map here. This is an accurate map. I looked him up. He was actually responsible for some of the, you know, so at the time the British were busy comparing all parts of the world and making it in pink. Do you know what the pink British Empire map looks like? I can tell you. A world-renowned mapmaker. And so he actually made this map. And the accurate part here, this is the South Dover Canal and it's planned. And then it actually shows the other ditches of the ditch company as they were. It says in small print here, "Our other ditch here would be unnecessary if we purchased their ditches. " Okay, so hidden wardenry actually got offered a million dollars for the ditch company if they would hand over the rest of their monopoly to make the South Dover Canal work. They declined because they knew a million dollars didn't exist. It's pretty easy. The old ditch company finally did find an investor. However, on his way back from visiting Nevada City and visiting Bear Valley, he was on a steamboat that exploded just outside Sacramento in January 1855. Quite a few people died in the explosion. He just got, as the newspaper called it, got maimed. He had a leg injury for life. Let's just put it that way. But these are saying he didn't want anything to do with California after that. It's like, "I want to get better. I want to go home. " And his name was never mentioned again up here. But at the meantime, there was this big argument between Aaron Sargent, who broke this angry op-ed, talking about how the ditch company were liars and blackmailers. It started to get nasty. But in secret, kids and company, they secretly started construction. So here we are at the bottom of the South Yuba River Canyon. There's a nice little waterfall there. And do you see what you see up in the background here? That's the South Yuba Canal right there. So it was about here that in February, the cat was out of the bag, and this secret construction, everybody had heard about it. And so Colburn actually persuaded, he went up to Omega, up to the miners up there, and got six years done to say, "All right, you've got to help me. These people stole my water rights, and they're building a dam where I want to build it. Will you help me kick them off?" And they're, "Oh, and if you can't, I'll give you free lunch. " So the miners said, "Sure, I'll come to the free lunch. " They came and had a look. So you can imagine 60 miners taking the day off for their free lunch, and Colburn and his partner, Ruby, they went up and they met somewhere around where this waterfall is. And there they found Charles Marsh, the surveyor, Dan Rich, the ditch guy, and John Dunn, with seven crew members. And they were starting to do severe surveying and get a dam together. And so obviously, there's 60 people. It was pretty intimidating. And Colburn started shouting. Marsh later recorded, "There were rude words, say. " So there was a bit of push in and shoving, but needless to say, they weren't going to move. And then during the free lunch, Dan Rich actually took some of the miners aside and said, "Hey, do you want to see the work that they've actually done? These people are trying to kick us off. " And they found there was about 50 feet of ditch that had been dug. So they'd been working on it for four years. And it's about two days' work back then. And so at this point, all the miners were like, "Oh, guy, you guys. This isn't worth it. We're out here. We've had our lunch. Thank you, we're done. " So, oh, and needless to say, Colburn says, "I'll see you in court. " So it leads us to the courthouse. So it's looking down Pine Street. So J. J. Jackson's is here. Friar Tux is here. Chocolate shops here. The courthouse and bike around. So Colburn sued. And he wanted them to stop work and injunction, $100,000 in damages. And basically they accused Kidd and company of trespassing. Now, there's a bit of a problem with that, is that a water right that's been dug back then, you can have a water right without actually owning the land. And they didn't own the land. Nobody owned the land. Actually, I'd be very fair. The Nissin'un had been on this land for about 10,000 years at this point. I'm not sure it was the U. S. government's, but it certainly wasn't going to belong to these guys. So, by December 1855, a judge agreed, "You can't trespass a water right. " Anyway, "We're not stopping you from building a dam. You go build a dam. We're not stopping you. " So the case was dismissed. And that was over. But, you know, Kidd and Moreton Reed, they weren't the sort of people just to let something go. So just saying, "Ah, we've won the court case. That's fine. " So it was around this time in the spring of 1855 that Kidd started buying up Hamlet Davis's credit. So the whole town worked on credit notes. So, you know, so when you went into the grocery store, when you went to go get some supplies, you know, basically you just made your mark if you couldn't write or you signed your name. It's like, "Okay, I'll put you down for, you know, $12. 50 or something, and then I've got a credit note. " From me to you to a name. And that was then used actually as currency around town. So you could actually take the credit note and you could give it to somebody else. And it's like, "Okay, just passing on. " So you could actually go and buy up somebody's credit if you actually wanted to really go after them. And that included going up, including getting into their mortgages. And so it didn't take long for Kidd to buy up all of it of Hamlet Davis's credit and Coburn's credit. And foreclosed on the United States Hotel, the Hannah Davis Hotel. So that's the communal cafe, is the United States, the site of the United States Hotel. And Davis's store, interestingly, was opposite where the cafe is. So this is where the chocolate shop is. So shortly after Hannah Davis was broke, he moved to Dutch Flats, started growing fruit and vegetables. Actually ended up being one of the first settlers of Truckee, actually. Started selling groceries and Truckee. Similar thing happened to Coburn. He just bought up the credit, forced them to bankruptcy. So needless to say, by 1856, a year later, those two had no interest in building a canal. They were broke. I want to get away from Kidd, particularly. So when the next time you go buy, yes, the Kidd Knox Building, George Kidd, Dr. William Knox, just remember that that property was acquired by putting somebody else out of business and driving them out of town. And coincidentally, they acquired the property in the spring of 1856 and decided, oh, we'll start building in August. They didn't know that in July 1856, the entire town was going to float them down. So actually, their building plans in August, this building was built just after the fire. They could have built it just before the fire and could have been unlucky, but that's one of the reasons they had that wonderful building. And you can see the roof. There's actually a big dramatic hole inside upstairs, as well as offices. It was used for law offices for a long time. Anyway, digress again. So with some of that backstory, we'll now actually just move on to some of the engineering. So this is the dam at the top of the south view of the canal. And this is where it starts to get interesting. So you can see, so this photo was taken in 1884, so about 140 years ago. You'll notice the snow. So here's the dam, and you can see the water is flowing over. And then here is the flume that runs around here. You see there's a little doorway, and there's nothing. That's actually a 60-foot tunnel that goes through from the back of here all the way behind there and comes and pops out. So that's the first thing they had to do, was they had to build a dam, and then the first thing they had to do was build a 60-foot tunnel through solid bedrock. And if you took this photo today, I haven't been able to get up to here. This is completely inaccessible. But if you took this photo today, you see where this tree is? The horizon would actually be cut off by the dam of Lake Spalding. So if you go to the dam of Lake Spalding and look down, you can actually see down into the canyon down in here. So in January 1855, we were still doing it secretly, marsh, dam, and a ridge, and a crew went up to camp in Bear Valley. And this is detailed in several court cases that I've looked through. And there's testimony about exactly where and when they were doing all of this. So marsh described how he chiseled the line. So basically, on that shack, doorway, on the rock behind, he actually took a chisel and marked out the line for where the tunnel needed to go. And he did that on January 24, 1855. So that's just amazing. And you can actually see, actually go back one minute and see without the words. So you can actually see here, there's a wooden ladder here. But I don't know how they get down there. And also, it must have been mild. I cannot imagine they were doing this with this, even this amount of snow. Can you imagine going up there, slippery rocks? Dave? So was this one of the first bedrock diversion tiles in the camp? Oh, is this one of the first bedrock diversion tiles? I would say yes. And it was certainly some of the most significant tunnel digging that was done in the 1850s. Yeah, that's a good question. So they finished the 60-foot tunnel by May. Costed $60,000. We'll get on to how they blasted that out in a second. But it was blasted out by hand. Dynamite wasn't invented until 1867 and wasn't commercially available around here until about 1875. So this was all done using gunpowder. Okay, so this flume. So the first mile, remember we were talking about the first mile, the current mile of PG&E still owns? Okay, this is what we're talking about. So it's 4,900 feet, pretty much along, it's not a vertical cliff. But vertical is relative. It's about 70 degrees. So you can't climb up or down without getting hurt. Let's just put it out. So the way they did this is they obviously started at both ends, but most of it was by hanging guys down on ropes. And so they would sit there with ropes, and it would be like a long swing, so you're sitting on a plank of wood with two of them, a piece of rope. And so a team of two, I need to put this down for a second. So a team of two, so one guy would be holding a very large chisel, a steel, so it would be about three or four foot steel. And the other guy would be holding a sledgehammer, so they're on swings, hanging down the mountain, and they'd be banging it, and the guy would turn it, and the quarter turn, bang, quarter turn, bang, quarter turn. Do it for 15 minutes, and then maybe switch jobs just so they don't get bored. It would take a couple of hours to drill an 18-inch hole. They'd pull the chisel out. They very carefully pour in gum powder, and even more gently nudge it in along with a safety fuse. So just imagine, you've seen pirate movies, right? You've seen a pirate movie, head of gum powder, safety fuse, like this, blah, blah, blah. Just think that, just think that. And so they used to form a series of holes to blast out the cliff. Holes are about two feet apart, 18 inches deep, boom. And then part of the ledge, then actually, and then they move on to the next part. And behind them, they would actually proceed with a rock foundation, building a dry rock wall to form the foundation for this flume. Okay, so we're talking about here. So let's give you the top mile, right? Okay, let's keep going. So we're going to take a look at what that looks like. So this is what it looks like today. So this is looking west. So the south Yova River is down here. Fair Valley Gap's there. And then the south Yova Carazon down Jordan Creek comes in from the right. So you can see the pipeline today. It's just going all the way along there. Isn't that amazing? Mile long. So just to zoom in a little, do you see how there's a rock foundation, so the dry rock wall? So that's pretty much the same dry rock wall that they built there in 1855 to 1857. And still they're holding up today's pipeline. Obviously the flumes rotted away. They replaced it with pipe. And so here's a different view. So this is looking back up the canyon. And in fact, you can see, so this is fairly accessible. And I'll tell you why in a second. But beyond here, it goes around a corner. And the top, like, quarter mile, completely inaccessible. It's really steep. I got as far as about here. And you can't climb up there without-- I wasn't going to go for a skin effect. But you can see all of this going on here. And what I noticed when I was over here, and I was looking at this photo, I was just going like, hang on a second. I remember there's a pond here. So I worked out, this is where the rock site is. So this is what the rock site looks today. So imagine covered in snow, right? So the pipeline ends here. And the pipeline-- so it's about 250 feet. Bit of a mess. And so we can zoom in. So here are the PG&E guys. And you can see the size. So there's a 50 inch pipe there. And they're building new concrete pylons to put the pipeline on. While I love blending PG&E for anything, I think I will say, if you're working day and night-- they weren't. They're working the day. It also might be a little bit-- it might be completed a little bit faster if you have more than five guys with pylons. You're saying-- the PG means-- sorry, the NID is saying, well, we're waiting on PG&E. It's like, uh-huh. OK, so the flume. So this is actually a model, a 3D model of what the flume looks like. So they did it in 12 foot sections. And so it has incredibly large pieces of wood, sort of a stringer that goes at the bottom. So it's an 8 by 12, 8 inches by 12 inches. So think about that. It's 12 feet long, and it's about 1 1/2 times the size of a railroad tire. So it's chunkier than a railroad tire. And that's just-- that's the large piece. And then you've also got these planks and then battenets. And so today we can actually see an example of this. So off Berger Road in Willow Valley, there's a section of the snow mountain ditch across the Never Sweat Ravine. And you can actually see this exact same design. And so this was from the 1960s. But nothing much changed in the flume design in about 100 years. What type of wood? I'm sorry? The usual? Oh, what type of wood? So a good question, what type of wood? Pretty much anything they could find. They loved sugar pine, was their favorite. But most of it was sugar pine, ponderosa, or fur. Was the things they used. Well, thanks for that question, because we're going to get on to a little bit more detail. I hadn't thought about what type of tree, but we'll get on to a bit more of that. So here's part of the steep part of the canyon. So it was in February. They'd been going about a month. A kid went up to visit. And he too, sort of the foreman, and the foreman must have said in a gruff voice, is like, "Oh, this is damnable country to building a ditch through. " That statement was actually struck out in a court record, because damnable was this curse word. Don't you be cursing in front of me. Kids just nonchalantly replied, "Well, it would have to be done. " What's sad is that two men died while they were building that rock foundation from gunpowder accidents. It was dangerous work. So it was by April, they surveyed the entire length of the canal, and then started clearing it. So we'll take a look in a little bit more detail about having some of the rest of it. Okay, so just to give you a proper view, I did that. So I went up last week to take a look, because I wanted to go see where the rock slide was. So this is just. . . Oh, just hit the right button. Just hit the space. Give you a sense of what the canyon looks like. So there's the rock slide coming to view here. So if you ever want to go for a walk up the Pioneer Trail, it's mostly accessible, but you have to do some rock sampling up here. But it's a pretty impressive view. Okay, so let's talk about once they got past the cliff. So they carried on with the rock foundation, six foot wide, sometimes eight foot wide, going all the way down Bear Valley. And so you can see here, so this is the modern flume that carries the water today. But you see here the rock foundation, doesn't it look pristine? It looks like it was built like last week. But that's the original rock foundation that used to have flumes sitting on it. It's an amazing condition. And in fact, while the modern flume goes by it, this winds its way down Bear Valley. It's in pristine condition, nearly all the way. So the seven miles required about 4,300 pieces of large timber and an additional 31,000 pieces of planking, which they had to be mill sonde. They actually dragged and carried up a two ton steam boiler to actually get a mill going up and down Bear Valley. Each mile also needed about 200,000 nails. They can't even catch them. So what we're talking about here is this is the seven miles and this is the main stretch of Bear Valley. Little in fact, before the last ice age, David can probably tell us more about this, but during the last ice age, Bear River used to go in the opposite direction. And then it got cut off by a glacier here, and that's why it now flows down here because it's not there once in a row. It's going to flow into the south view. Okay. So this is the modern flume. I have to say, this is just a fantastic picture. It's just a model of engineering for the modern flume. So what you've got to understand is that in constructing this, the whole seven miles of flume, so about 2 million board feet of lumber and about a million and a half nails, it was quite a sizable project. And the whole thing has to be replaced every 10 to 15 years. No, they tried to repair it. So some pieces of it lasted 20, 30 years, but other pieces only lasted five or six years. The whole thing had to be replaced by regular. So finally, as they were going down to the end of Bear Valley, they reached the ridge and a marsh root realized that if he cut under the hill with a tunnel, he could actually save about a mile of ditch. And so they called it Little Tunnel. And this is where the little tunnel emerges in steep hollow. And this is what it looks like when it's empty. You can actually see the light at the end of the tunnel. It's about 300 feet long. So the original was about seven foot wide, about six foot high. And then in the 1960s, they lined it with concrete. So it used to have a flume running down the middle. Again, it had what's needed to be maintained. So they replaced it with a lined concrete mess, as you can see it today. OK, so once you get through the little tunnel, you're now into diggable dirt. So they had eight miles of ditch up in an up tunnel. So this section is from across the two forks of a steep hollow. And it's actually about two miles across here. But they had eight miles of zigzag to make it up around the earth. And steep hollow, creep, it's because it's steep. So here you can see the modern ditch just winding around the hill. So you can see why there's lots of snakey turns. And so once you get to here-- so I actually have to just go back for a moment. So this is likely my favorite story. So we're now-- this is the flume back in Bear River. And this is about where-- near where it crosses 20. So if you're going along 20, just come over the crest of the hill down into Bear Valley, going down the hill, and you cross over the flume right there. And it's nearby here. And so this is also perhaps a public service announcement for NID. You'll see why. Just safety first. So there are a couple of guys. They're named a couple of miners from Omega, named Ostrom and Van Franken. They're out hunting. And people used to use the ditches as sort of walkways, as thoroughfares, because there weren't any roads up there anywhere. And so they're out hunting. And they're on their way walking back towards town. And they're walking along the south view of the canal-- the flume of the south view of the canal. So about two-finger paths, four inches. You've got to be careful. Well, Van Franken slips, and he follows. And he must have dislocated his hip or something. But he couldn't walk. He couldn't move at all. And so they're like, oh, my goodness. OK, what's going on? So Ostrom manages to find-- so they're always doing maintenance to these flumes. So Ostrom manages to find a plank. And he puts Van Franken on the plank. And he's dragging him along the top of the flumes. So he's got to make sure he doesn't fall. He's dragging the plank with a guide. So they make it all the way from somewhere along that valley-- I'm not sure-- but heading downstream. And they make it all the way to Little Tunnel. And then he has to crawl through. So there's a flume, seven-foot high-- six-foot high. But he can crawl along the top of the flume inside the tunnel. And then he emerges back where we saw him. And then-- OK, so go back a slide. There you go. So then they emerge through Little Tunnel. And they're going down here. Now, he's going to like, OK, well, I can't carry him. I can't carry him on the plank down here. So what am I going to do? So there was a bunch of other lumber left over. So he built a little raft that could fit in the canal. The problem is, by the time you put Van Franken on top of the little raft, there wasn't enough water. And it was kind of sinking down. And so he got some more lumber. And he went and built a little dam with the lumber. And the water rose up. And there was enough water to float the raft with Van Franken on it, down to the dam. And then he'd take down the dam and the water-- he'd run down another few hundred feet. And then it all knelt down. And the water would float up. And he'd put him down. Three miles down here. He did that. It took him six hours of walking on top of the flume through the tunnel, and then three miles of dam building on the canal, until he finally found a house and found somebody, a horse and a wagon that could take him into town. But I have to say, it's like, talk about perseverance. It's like, good rescue job. Say he first. Do we walk on top of flumes on friend ID? Think about it. Oh, sorry. That was actually the story. So from the Nevada Journal, from 1861. So you can actually look up-- if you look up Van Franken, an Austrian, California digital newspaper collection, I can see the link as well. It's fun story. OK, so the dish. So this is actually what it looks like 100 years ago. It's actually 100. And I think I found the exact spot 100 years later. Except it's lined with concrete now. To cross Sea Polo Creek, they built a flume. Because they could either build a dish all the way up, and then all the way back down, or they could actually just sneak across. And so they built a 500-foot flume across Sea Polo Creek. It's about 160, 200 feet off the creek bed. 2,000 man-hours of labor from competitors to build it. And less than 10 years later, covered in snow, a hole in clutch. Oops. So they thought, hmm, this is a little bit too big. So let's go further up the ravine, and then we'll cut across. And there will be a shorter cut across. So they hardened half the length of the flume. So it ended up with a 200-foot flume. And then on the other fork of the Sea Polo Creek, there's another 200-foot creek. And this is what it looks like today. So there's a modern flume that goes across the same spot. OK, so the final stretch is this piece to go from Sea Polo over into the Deer Creek watershed. And so they had to build a tunnel. So this is what it looks like inside a big tunnel, a 3,000-foot-long tunnel, 8-foot wide, 10-foot height. 8-foot wide. And you just have a large flume going through the middle. It saved about three to seven miles of ditch digging. But the tunnel, they quickly realized-- they'd been at the whole canal just for a few months-- and they realized that this was going to be the showstopper. This was going to be the longest, hardest project that they were going to be working on. And so by September 1856, they had 200 people working on this. This is serious engineering. And to give you an idea, this is if you've ever been up off Lowell Hill Road or Chalk Bluff Road or up near the Deer Creek Powerhouse, the roads aren't very good now. [LAUGHTER] Weather? Yeah, January 1857, there was 12 feet of snow at either end of the tunnel. So how do you start moving stuff around if you've got some? So here's a section of the timber inside the tunnel. And so a lot of it's concrete lines now, but there are still some parts that are either timber or how it looks originally. So it was going so slowly. They actually thought, oh, we can dig a hole. We're digging like this. We can dig a hole in the middle, go down, and then we can actually start digging out sideways. So they actually had not just two faces, but they had four faces. And so it's dull to see, and they could put a lot more people working on it. And what's interesting is that they never filled in that construction shelf. PG&E obviously realized it was something. And in 2015, PG&E actually filled it in. And they backfilled it with foam, waterproof clay, eight feet of concrete, and then a rebar filled concrete pad on top. You can't accuse them for not doing it properly, at least. So this gives you an idea. So the water's coming in from the right, coming out from the left into Deer Creek. This just floats right into the top of Deer Creek. And here's the mid-construction shaft. So this is from 1955 when they started lining up the concrete. OK, so while they were finishing off the tunnel, because it was delaying the project, everybody was waiting for the water, they actually started, what are we going to do with the water when it starts coming down up now? And so they started building an extensive ditch network. So south here with the canal here, right, big tunnel, a chalk-glove ditch. And this part is still active, except that's the Deer Creek powerhouse right here today. And then they go down the start side. But then they built the ridge ditch that went all the way down here to the top of Rock Creek. So this is the Washington Cervancy area of 5-20. And so all parts of White Cloud, Jefferson Creek. And they also had spur there, long spur, going down to Alpha and Omega. So that's 30 miles, 13 miles, 10 miles. So with south here with the canal, they could get water to nearly anywhere in the western Nevada county. The only limitation was elevation. They couldn't pump it up. No question? >> When is the ditch that goes along the Bear River? >> Oh, okay. So what was the ditch that goes along Bear River down here? So that's the Drum Canal. And so that's the primary water source that goes down to Dutch Flat and also then down to Auburn. And it also provides water that also down to Rollins and also as the theoretical backup for Scott's flat. Another question? >> Were the Chinese involved in any of the labor? >> Oh, good question. Were the Chinese involved in any of the labor? So I looked at this in detail. And one of the things is the use of Chinese labor is very well documented by the Central Pacific Railroad in construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. I can tell you that for all of this construction, every single last piece, there was no Chinese labor involved at all. And the reason is because it would take away work from the honest Joe. So later on, so one of the blue tent ditches did actually try to use, they switched out half their construction crews. And this was later, it was about 1870, yeah, late 1870s. They switched out half their crew to help construct the blue tent ditch, which was next to the one that we saw on the megafloon. They started for a couple of weeks, and the miners from North Bloomfield, from Malecok, came over with, essentially you can imagine them coming over with pitch box, but actually they came over with sledgehammer's. And they came over and started smashing up dams and flumes and anything they could find that would be built with Chinese labor. And so within two weeks, the construction company, the blue tent mining company, had negotiated with the miners to agree that they would only use white labor. So there was deliberate industrial sabotage at the time, so any time before, at least for gold mining and for digital construction, it was industrial sabotage was used for any company that was using Chinese labor, which in itself says an awful lot about what was going on. That's a really good question. Okay, so if you want to see a rich ditch, you can actually still see it. It's quite large, but this is what took water down to Washington and always blue tent. So some of the water that had made it to the city was coming down here. So this is just below Highway 20 near Washington Road. Okay, so just to nearly finish up here, so by Thanksgiving 1857, the tunnel was finally finished. All of the flumes, all of the ditch was finally finished, and water was started flowing. So the total cost was about $600,000, which today would be about $20 million. Although, let's think about this. So do you know how the cost of lumber has gone up, right? So can you imagine trying to pay for that number of 2 million board feet of lumber? I think it would be an astronomical cost if you were trying to do that today. Although, you would normally be done by hand. So water was flowing down into Deer Creek, and then they picked up the water at Scott's Flat into the Snow Mountain ditch and other places. What's interesting is that their competitors, because they still had some there, were more than happy to borrow the water out of Deer Creek, because the south end of Mount Company were just literally using Deer Creek as a cheap way to bring water down to town. But once it was in a public waterway, like Deer Creek, it was anybody's water. And so, particularly famously, Amos Laird, he built a cascade ditch, a cascade ditch named for the Cascade Falls, where the dam of the cascade ditch stopped. That's where the cascade shawls come from, for example. So it took until 1861. They bought up all of Laird's credit, put him out of business, and he went to the exile in Montana. Although interesting, he did come back to retire, he retired in Washington. So, but the same thing, they didn't take to competitors very lightly. So, and you can see here, the left-hand part of the building here, well, it's today, it's the Chamber of Commerce downtown. That used to be the office of the South Ewe of Mount Company, and was the headquarters of the company from 1857 until 1880. - Can we need some help? - Oh, I see. - Can anyone watch? - Yeah. - Thank you. - Is there anybody with some medical training in the house? - I have CPR. Is there a hard going? - Yes. - She's a contact passer. - I need to call 911. - Yes. - Does anyone call 911? - She's home. - What's your name? - Hi. - Hi. - Hi. - Yes. - I'm here to meet you. - Is there a call? - I'm here to meet you. - I'm here to meet you. - We'd rather meet you.